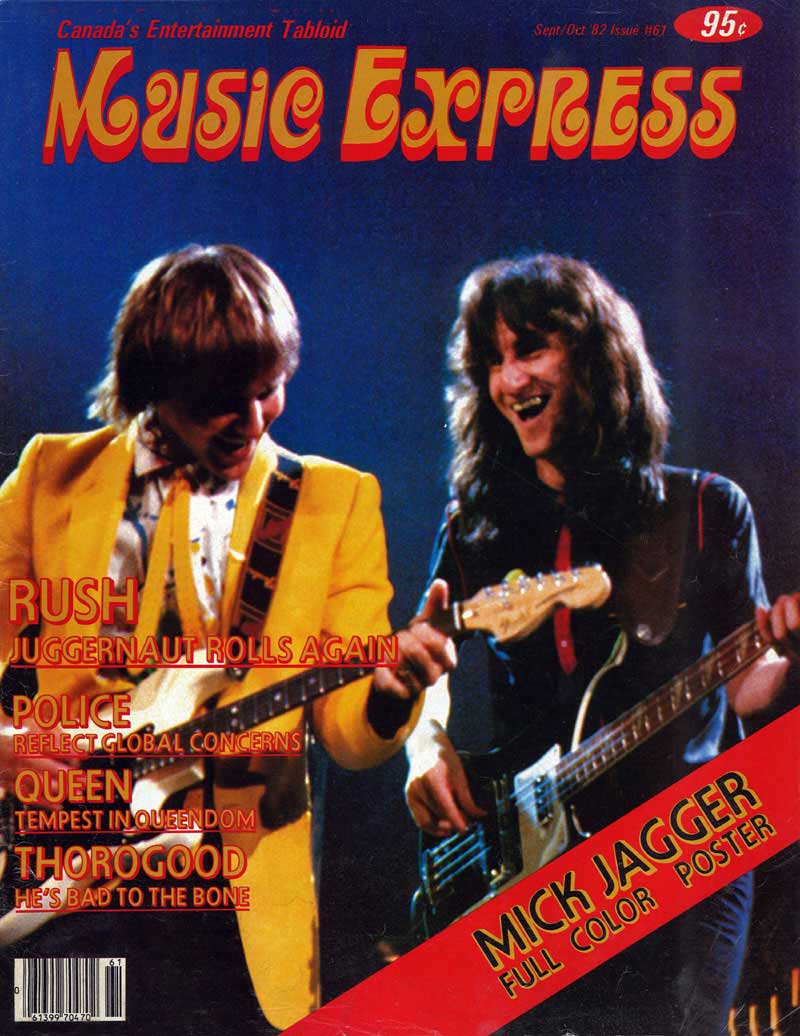

Neil Peart: New World Man

By Greg Quill, Music Express, September/October 1982, transcribed by John Patuto

You have a reputation for being able to outclass yourselves with each successive tour. I've heard you have special plans this time around which won't increase production costs and ticket prices. What are they?

Monster productions have started becoming a bit incestuous. In our case, there are no expectations for making a profit on the road - a tour is something that's meant to pay for itself and if it pays you musically, by allowing you to improve your work and develop new ideas, so much the better. That's the real value. But when ticket prices start climbing over ten dollars, I get a bit nervous about it.

Sound is always our prime consideration - it can always be improved on. Technology is always advancing. And, of course, we've just spent months in the studio under perfect sound conditions - trying to reproduce our album live, with all those variables, is a real challenge. During the last two tours we've tried to get more and more of our sound system up in the air, allowing for greater fidelity, eliminating indirect signals. This time we'll be using "time aligned" speakers, which slow up the path of high frequency sounds so they reach the listener at the same time as lower frequencies.

In lighting we've tried to go for rearrangement rather than growth. Lighting systems have tended to get very much out of control in the last few years - some bands carry five and six semis full of equipment - and we've given the no to that. We've been trying to present the lighting effects in a more original way. More imagination and less quantity.

And you have some official NASA film footage on the shuttle launch?

Yes. One of the tracks, Countdown, on the new album is a recreation of our experiences attending the first Columbia launch in Florida. Because we have some friends at NASA (Columbia astronauts among them, who have subsequently "partied" with Rush and attended their concerts as special guests), we were able to get hold of the actual sound tapes - which we used on the record - and a whole lot of original footage which we'll be able to use in our rearscreen projections. It's worth a lot of thought and investment to us; for one thing, it adds so much to the show. Each year we have one or two new films specially shot to accompany certain songs, and other films get recycled as some songs get dropped and others added.

Which song will the new film illustrate?

Subdivisions, an exploration of our background as children of the suburbs. Of course, a great number of our fans probably have the same sort of background - that's a universal in this day and age. The film will be a surreal representation of a real situation.

The quality of Rush's recent, most successful work, I feel, parallels almost directly your development as an incisive, articulate and stylish lyricist. From Permanent Waves till now, all the positive changes in the band can be traced to the strength of your lyrical contributions: Geddy has become a far more believable and sensitive interpreter of your work, relying less and less on pure histrionics, as your own craft has become increasingly refined. The band's ensemble work seems cohesively organized around the phrasing, the meter, the imagery and atmosphere of your lyrics. Is that a fair observation?

That's wonderful! Somebody noticed!

That's false modesty.

Well, a lot of people don't pay attention to lyrics. As a listener, I don't. The only reason I put so much into writing is because I'm the one who's doing it. It's the old AngloSaxon ethic: If it's worth doing ...

Development? During Rush's early days my reading preferences - and they influence the way you write - were Victorian-era English literature: Thomas Hardy, Dickens; fantasies and science fiction - all of it written in a timeless, old-fashioned, ornate style. So my lyrics were all very ornamental. I'd take the germ of what I wanted to express and then dress it up, decorate it the way a Victorian house might be decorated, with all the gingerbread and fancy shutters.

Over the last couple of years my reading habits have followed the historical path of prose writing, and I've finally discovered the twentieth century, the New World writers like Scott Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Faulkner, Barth - vigorous, economical writers who don't use adjectives for their own sake, but who succeed in saying in a single phrase what Hardy would have spent a couple of paragraphs on. Now, more and more, I'm trying to find some fundamental thing that can be expressed simply, where the choice of words is ultimately precise - no other words would do. I've come to reflect on the exact meanings of words and word choices.

The rhythm, of course, reflects that simplicity. It's somewhat deceptive, because I spend a lot of time on it, but in the final analysis, it's some very simple thing. Hemingway wrote only 500 words a day, a very low output but he agonized over his choice of words; his sentence construction was often illiterately simple - he'd eliminate so much, what was left would be almost unintelligible. I've found that approach very useful in lyric writing.

In most songs on Signals, there's a simple lyrical crux. In The Analog Kid, "Too many hands on my time/Too many things on my mind/When I leave I don't know/What I'm hoping to find/What I'm leaving behind ..." In Losing It, "Sadder still to watch it die/Than never to have known it/For you - the blind who once could see - /The bell tolls for thee ... " In The Weapon, " ....fear/is a weapon to be held against us." And Subdivisions, "Sprawling . ../In between the bright lights/And the far unlit unknown ... "

Yes, "the bell tolls for thee ... " Obviously I owe Hemingway a larger debt of gratitude than I've acknowledged! (laughs) And "too many hands on my time" comes from, of all things, a Styx song that had some reference to "too much time on my hands." I just turned it around. There you are - a Rush song directly inspired by Styx! The truth is out!

I'm trying for observations without moralizing. In the past I did tend to get quite preachy - which was unavoidable, of course, because of what I was reading.

And yet you're political in what you choose to write about ...

Oh, yes. There are concerns I want to express, but I think I've become more diplomatic, more tactful. If you don't want to hear it you don't have to - there's often more than one level of meaning. That's one of the hardest things to learn - how to say something without yelling it.

And Signals has a cyclical framework. It opens in suburbia, on the edge of "the far unlit unknown," contemplates escape in The Analog Kid, explores universal human imponderables - the essence of our humanity, sex, religion, old age - and ends with actual escape to the stars in Countdown ...

Ah, you noticed that. We were hoping no one would. It's so unfashionable these days to construct grand concepts. We're being closed mouthed about it. Some people, and I don't expect there'll be many, will be insightful enough to catch it. Although it's interesting that you, the first writer I've talked to about the album, did pick up on it.

What does your current reading list comprise?

Well, there's the pile of books I'll be taking on the next tour - a couple by Theodore Dreiser, whom I've never read before, one by Virginia Woolfe, whom I've never read either, Washington Square by Henry James, recommended by a friend, more Scott Fitzgerald, whom I regard as something of a bridge between the old romantics and the new realists; more Hemingway, Faulkner...

A heavy load for one tour.

Well, on the road it's so easy because there's so much dead time - between the sound check and the show, riding on the bus or on the plane. I do so much reading on the road that I don't have to do any at other times. I'll do three or four books a week.

Geddy told me you're harbouring thoughts of writing some prose yourself.

I hope to, yes. That's why I've been writing the biographies and album notes for the band for the last couple of years. I have so little experience in prose writing, and sentence structure is something I still have a lot of difficulty with - I'm used to dealing with the conciseness of song lyrics. In some ways that's very easy, it's so concentrated. You know when a word doesn't belong in a song. In prose there are wider possibilities, and consequently you have to set your own limitations. The changeover has been quite a challenge.

I've been writing some articles for a trade magazine, Modern Drummer. It's interesting for its own sake, but it's also giving me a lot of valuable experience in handling syntax and grammar, making up for a lack of formal training. If you have a love of words, I think you also have an instinctive sense of what's right and what's not.

Drummers aren't generally considered to be the stuff writers are made of.

No. And I don't know why - they have so much in common: rhythm. I think it's a role they've been given, like women. Drummers are perceived as dumb guys who hit things, but many drummers I know are really literate people, communicative and sensitive.

Writing came to me by accident - I didn't really have designs on it. I'd done a couple of songs before I joined Rush, and of course, I've always loved literature - it's been my main passion. But I never thought of transferring it to music till I joined this band and found no one else really wanted to write lyrics. I thought, well, there's nothing to lose - I'll give it a try. Now it gives me a lot of pleasure.

It's possible to read your lyrics and imagine them being treated in almost any way other than the way Rush treats them. Do you ever feel your words and the band's music don't quite mesh?

No, although it's an interesting question. Many of the rhythm shifts and style changes the songs go through are actually built into the lyrics in some way. Other times we're deliberately perverse. In The Analog Kid, for example, Geddy and I were talking about possible musical treatments. When you read the lyrics, you're right, it would have made a lovely ballad or a medium tempo soft rock piece. We said, all right that's what the lyrics suggest, let's not do it that way. Let's take an entirely different point of view, using two diametrically opposed dynamic approaches - hard rock for the verses and something really watery, almost angelic for the choruses, cut off the thrust of the song and backpedal.

I know that when you go off to the farm once a year to write, you spend your days in one building writing words while Geddy and Alex are in another building working on melodies and arrangements. How does the synthesis actually occur?

Well, nowadays, lyrics seem to come first, simply because they establish a framework or a mood. Sometimes the other guys come in with lots of musical ideas that don't have a place till the song is written. For example, another interesting exercise in juxtaposition is The Weapon. I had these really doomy, black images in there and Geddy had written a lot of-the musical sections for it at home, as a sort of electro-beat, modem dance exercise. We weren't sure that we'd ever use it.

Now, because Geddy has to sing the words, a lot comes down to decisions he and I make. He persisted with his idea that we should approach the treatment again from a really abstract point of view, juxtaposing his electronic dance music with the dark, doom-laden lyric of mine, and making it work somehow. And I think we did. I'm really glad it took the brooding, heavy quality away from the lyrics.

About The Weapon, I'm not sure of its intent. It could be construed positively or negatively ...

The Weapon is part of a three-piece I've been working on, called Fear. It has to do with the way fear is used as a psychological weapon against us all. To bring it down to mere words, I'm dealing here with religion and religiously-controlled government - not necessarily with war or the nuclear arms race.

You have a reputation for being withdrawn, the one member of Rush who's reluctant to be interviewed or photographed. Why?

It's not that I don't like being interviewed or photographed - I don't like seeing my picture in print. I'm so tired of being visible, I had to make a change. I couldn't deal with it personally. When people come up to me in a public place, I'm not flattered at all - I'm just embarrassed. The only ways I could cope with it were either to drop out of public life - which is not possible because what I love doing most is playing music and writing songs, or to change the nature of my relationship with the world at large, so I could still do the work without being Famous Face Number Three.

I'm not reclusive by temperament. I'm anti-publicity by temperament. A new way of handling this lifestyle. It was a hard decision to make and harder still to institute. People never understand the real reason you don't want your photo taken - they think you're egocentric when, in fact, I'm quite the opposite. Limelight on Moving Pictures was my first attempt to deal with the problem, but, of course, people still didn't understand what I was trying to say there.

All I can do is try the best I can, subject to my own integrity. Myself, I like to be left alone to do the job. I love the work. I love travelling, I love playing live and I love making records - but I don't like being famous. It's a hard thing to reconcile.

I lead a reasonably quiet life in St. Catharines. I'm married, with a four-year-old daughter - and I try to stay out of things. Something Todd Rundgren said once really hit home with me: the more popular you become, the less accessible you have to make yourself - out of self-defense. That's what's happened to me. I've stopped going places; I like staying home a lot. I get enough social life, of course, when we're on the road.

Geddy creates the impression that Rush on the road is decidedly unsociable, that the band is protected by a bubble, ensconced in a private inner sanctum.

Well, that bubble includes 30 people. You can't really be unsociable with 30 people. But we have our friends within that group, and some of the people in our crew have been with us for up to ten years now - we have close relationships with a number of them, all inside the travelling circus. It becomes a social life unto itself. There's a constantly developing circle - just like your own circle of friends in the city, with whom you might go to a movie on a day off, or visit and have dinner with.

Do you try to control the atmosphere, the behaviour of members of your entourage on the road?

I don't think you have to control it, just direct it. We try to set an example; we aren't autocratic as far as our crew is concerned. They all know they have a job to do and as long as they do it, they know nothing will be said. We try to be open and genuinely democratic. It's not us and them at all - it's all of us together. So I don't think you have to control the atmosphere, just set parameters - then the atmosphere will be automatically as good as it can be on any given day.

By adhering to no other standards than your own, are there any real challenges left for Rush?

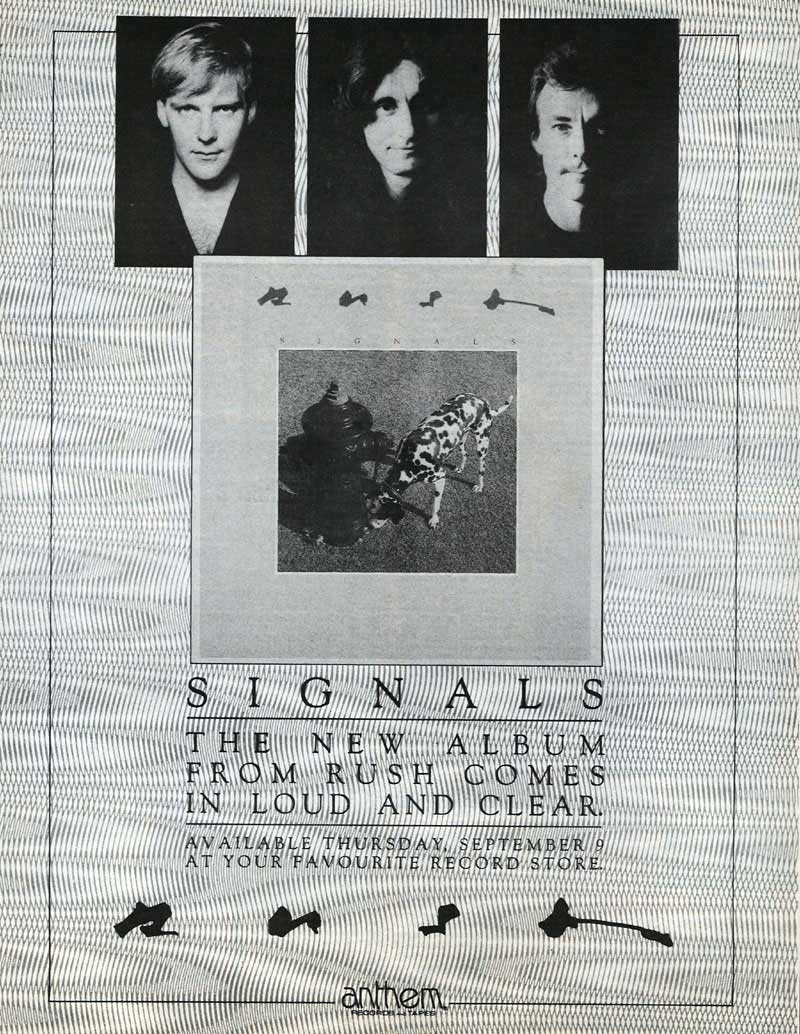

In some ways, once you've set aside commercial considerations and operate on your own system of values, the security is gone. Past success gives you freedom but it doesn't give you any satisfaction. One reason this new album was so difficult for us was because we were trying something different with a lot of the songs - and with texture, the overall sound. There's more synthesizer work this time - and even down to fine points, we went for different types of drum sounds, different ways of mixing things together. So, even though we've made eight or nine albums, all that experience didn't serve us all that well. Signals took us a long time because we were trying not to repeat ourselves.

Past success gives us the independence and the ability to decide when, where and how we're going to work - and no-one else has the right to gainsay that - but, at the same time, we're going in each time with a fresh slate. One approach is to assume that a particular album is as good as the last, and that people will buy it on that basis - that attitude doesn't work for us. We're concerned about making something that's both different and better.

So there's no real security. The self-doubt never ceases, especially on the road, where you tend to judge your whole existence by last night's performance. Sometimes you resent the accolades, because if you come off stage knowing you haven't played well, it's worse to be applauded as strongly as if you had. Especially when you know people who matter respect your ability - other musicians, critics, music pollsters - and it weighs heavily on your conscience to realize many of them were probably in the audience the night you performed below your own standard, or their expectations. You feel a bit of a fraud. The live situation brings a lot more angst into your life than recording does, where you're able to set standards for yourself. On the road, you have to live up to those standards.

Would it worry you to have an album that satisfied your own requirements slagged off by critics?

Yes ... it would. You don't lose the sensitivity unless you're trying to. And I must admit a really scathing review is still a painful thing. Let's face it, it's you they're talking about, and it's hard to shrug off. And there are lots of people who hate us, believe me. That's nothing new.

We've had cases where writers who've been kind to us, given us insightful reviews, have suddenly hit on an album they didn't like, and reviewed it accordingly, from the point of view of a disappointed follower. I think you pay attention to those reviews, to be honest, to writers you respect who offer a considered opinion, good or bad. Mind you, I'm only talking about 0.001 per cent of critics - but, nonetheless, what they say is important. You can't be arrogant about it. My friends' opinions matter, and certain critics you have to consider peers.

Is there an inclination in the band to do less touring?

It's a fine line. In some ways, being on the road is the best thing for a musician. I find that at the end of a tour I'm playing a lot better and I've learned a lot of new things I've had time to work on. And I've seen many parts of North America and Europe and have a wealth of new input, impressions, ideas, faces. Those are very valuable things to be able to bring to the studio, so I couldn't see us being just a studio band. That would alter our perspectives, our growth as musicians and, in my case, as a writer.

With this album, we'll still be doing six months on the road, but three months at a time - staying out till December, then taking a break and going back in the early part of next year. Just so we don't kill ourselves.

Does the rise to worldwide popularity of other Canadian bands, like Loverboy, whose recent achievements have eclipsed Rush's - at least in terms of media coverage - ever concern you?

I'd have to say no. Not to be arrogant, but it's something that has never mattered. We've never been competitive in that way. Our competition is against ourselves.

Mind you, we have to judge ourselves according to standards set by musicians we admire, but that's not competitive - more striving, I suppose. I like to make sure I'm abreast of changes and developments in music, of things being done by new, interesting bands. We certainly want to incorporate those kinds of changes into Rush's music.

Any names?

Sure - I'm just worried about the ones I'll miss. There are a lot of neat things happening right now - Ultravox is a band I've liked for some time; U2, especially their last album; more frivolous things I wouldn't use as a standard but like anyway - Spandau Ballet; I love Talking Heads, and always have - and I think they've made an impact on our music; Peter Gabriel's last album I think was a milestone; New Music is a band I like for the things they do around a simple framework; Simple Minds, for the same reason; the new Japan album is a wonderful piece.

There are musicians too: Bill Bruford is a constant inspiration to me technically. And there are others. The bands I mentioned are remarkable for their style, for inventing new approaches. Certain reggae artists I'll listen to just for bopping along with.

Geddy gave me the impression you're not really conscious, as a band, of the necessity of keeping on top of other developments.

Yes, we are. Geddy is too, to an extent. I have CFNY (a Toronto new music-oriented station whose slogan, The Spirit Of Radio, inspired Peart's lyrics in Rush's Permanent Waves hit of the same name) on pretty well all day long - partly for pleasure, partly to hear what's going on. Another thing I've been doing the last couple of tours is compiling the tapes played over the PA system at our shows during changeovers, or before the concert. I've been looking at that as if it were my own private radio station, taking my favourite songs from unusual bands that people wouldn't ordinarily hear and putting them together in a radio format. It's a way of exposing some of the bands I'm interested in that wouldn't normally get airplay on your average Top 40 AM station.

Are there any Canadian artists, writers, musicians, bands for whom you have particular aspirations?

At the risk of being lynched. I must confess I'm not at all nationalistic. The more I learn about the world, the less nationalistic I become. I really want to get one of those Citizen of the World flags like they use on boats and hang it over my house.

I love Canada geographically, but I'm certainly not one of those people who believe it's miles superior to the northern United States - to which it's identical. I think the state of Michigan has as much to offer in beautiful topography and nice people as Ontario. I'm very, very tired of nationalism, I must admit.

As far as musicians go, I have aspirations for musicians in general. Remember, there are at least as many frustrated musicians in Canada as there are in England, or ... Ohio. It's of equally great concern to any open minded person that all real artists get a break. The doors are open in Canada now. There's no reason any more for the excuse that Canadians can't make it unless they go to the States. That's been proven wrong, amply. I don't see any need to be specially concerned about Canada any more - which is the way it should be. We have as much good and as much bad to offer as anywhere else.

Of performers who happen to live in Canada, FM is a band I've always admired as musicians and people (FM's violinist Ben Mink performs a scorching solo in Losing It on Signals. The band was recently signed to Rush's Anthem label); Boys' Brigade, with whom our sound man, Howard Ungerleider, has done some work, should have a good future if they can hold it together; Rough Trade, of course, do interesting things in a bizarre sort of framework. It's too easy to say that bands become successful because they happen to hit on the right formula. Originality pays off.

There is real individuality in Canada, but not where people look for it. It's there, it's always been there - in the laurentians, in the Prairies, out in Vancouver - but you have to get out there and find it. Nothing will stop true originality and no amount of flag waving can accentuate it. It just is. It's special. But you can't tell people what's under their noses.