The Saga Continues

Alex Lifeson and Geddy Lee divulge some of their trade secrets

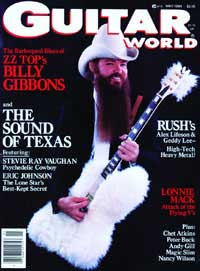

By John Swenson, Guitar World, May 1984, transcribed by pwrwindows

Few bands have realized the potential for creativity in the heavy metal format that Rush has nurtured over the years. Bassist Geddy Lee and guitarist Alex Lifeson started the group in various basements around their hometown of Toronto in the late sixties emulating the hard rock sounds of the Who and Led Zeppelin. "We came from pretty much the same neighborhood," Lee explains. "We met in eighth grade. Alex used to borrow my amplifier all the time. We played in coffee shops for chips and gravy. I worked in my mother's hardware store for a while. Alex worked in a gas station. We were playing the English blues-John Mayall, Cream. Alex would pretend he was Eric Clapton, I would pretend I was Jack Bruce, and we'd play 'Spoonful' for twenty minutes. Then came the big crunch , heavy metal, and we thought, This is it!"

Lifeson and Lee's dedicated approach won them an underground following around Canada, but the Canadian music scene wasn't taken as seriously back then as it is now, so the band's demos were all rejected by the major record companies. Instead of being destroyed by this failure, the band believed enough in itself to form their own label, Moon records, to release their debut album, Rush. Without the benefits of commercial distribution the record became a regional hit in the midwest when fans of the group's live concerts demanded that their local record stores order the Ip. The Chicago-based Mercury records could hardly ignore what was happening right under its nose and signed Rush, re-releasing the first album.

Drummer Neil Peart joined at that point, replacing the original drummer on Rush, and the band hasn't looked back since.

Rush was pretty much built around Lifeson's extended solOing on subsequent albums like Fly by Night and Caress of Steel before Peart started writing the science fiction concept albums that became the heart of the band's identity for most of the seventies. Their breakthrough record, 2112, developed an epic tale of a future hero who leads a revolution through music. The album also marked a musical evolution for the group, which produced the kind of space-music associated with bands like Pink Floyd. After 2112, A Farewell to Kings and Hemispheres continued successfully along the same lines. The group's tremendously popular live shows were built around these stories, buttressed by elaborate visual correlatives on a giant screen behind the stage.

It wasn't until the 1980 album Permanent Waves, though, that Rush came up with a sound that led to heavy radio airplay and hit singles. Under the influence of rock's new wave, the band adapted its approach away from many of the excesses associated with heavy metal. The record scrapped concept albums in favor of shorter songs, which allowed for hit singles ("Spirit of the Radio") and better critical response.

"IT WAS TIME TO STOP THE CONCEPT stories," Lee points out. "What you have to say ends up being very nebulous, because you're concerned with this big story. You try to make the story right, you try to evoke the right moods, and invariably sixteen different people come up to you and tell you sixteen different things about what you're trying to say. That's fine, because that's the way it really should be, but for us it was time to come out of the fog for a while and put down something concrete."

With Permanent Waves and the followup, Moving Pictures, Rush laid the foundation for their current arena success. The double-disc live set Exit...Stage Left provides awesome testimony to the band's in-person power. The live album also marked a period of creative woodshedding during which the band was given the opportunity to develop new ideas. "The last time we had a creative hiatus to do a live album," recalls Peart, "it gave us so much time to prepare ourselves that it gave us a dynamic leap in progression."

The band's most recent album, Signals, exhibits just such a conceptual leap. Geddy Lee has began to rely more heavily on electronic keyboards for writing and arranging the group's material. "One of the changes that it's gone through," says Lifeson, "is that in the past Ged and I would sit down with a couple of guitars or Ged with his bass and me with guitar and start working on ideas. Now that he's playing a lot of keyboards, he will work something out on them and then I'll just get the chords from the keyboards so that we'll switch the focus back to the guitar, but using the melody and the chordal movement from the keyboards."

"Sometimes," Lee adds, "we have to figure out whether it's best to keep it on keyboards or transpose it to guitar and have keyboards support it. That's what we're sort of going through now. With Signals, we left a lot up to the keyboards and we thought guitar took too much of a back seat. This album we're trying to change the emphasis a bit using the keyboard to write with but at times letting the guitar take over what the keyboard was going to play.

Lifeson points out that this approach "makes the guitar parts more interesting. Often when you transpose keyboard chords to guitar you end up playing chords or combinations you never really think to play."

Lee agrees that the keyboards enhance the harmonic structure' of his writing. "Working with keyboards presents a whole different layout, so when you look at the keyboard sometimes you can string a set of notes together that you wouldn't have thought to put together on bass or guitar.

"If it's a good part that we like, Lee continues, "Alex will learn the part from keyboards, and with a few adjustments it will take on a new dimension, and then I'll play bass. Then we listen to how the part changes on guitar, then we see if the part is strong enough on bass. If it needs enhancement then maybe I'll add some other kind of keyboard part until we find out what suits the song best. With 'The Body Electric' it worked that way, we kept going back and forth between guitar and keyboards. I would rather play bass if at all possible. It still feels most comfortable."

RUSH IS A CLASSIC POWER TRIO, AND as such the role of bass guitar is extremely important. Lifeson points out that he feels the bass is necessary for his guitar to sound well. "Generally, I prefer playing with the bass," he says, "with keyboard enhancement. Just even a sympathetic note under everything allows me that much freedom to do different things chordally or doing a combination of notes with chords when you have the bass providing other melodies or harmonic content to what I play. In that respect it's a lot nicer to play to the bass than to a keyboard."

Though Lee has traditionally played a Rickenbacker bass, he recently added a snub-nosed Steinberger to his arsenal. "I like the Steinberger a lot," he says, "I started using it just before the Signals tour, somebody said 'try this' and it sounded great. It's got quite a different sound from my other bass- the bottom end is really rich, deep, it almost has a synthesized bottom end. It doesn't sound like it should sound going by the theory that big-bodied basses have a deep, resonant sound. This has got a little plastic body with a battery in the back and the bottom end sounds rich as hell. It doesn't sound natural, but it sounds real interesting. On some of the new songs I like the punch of the Steinberger but on some of the older things like 'Digital Man' I still use the Rickenbacker. I still love the Rickenbacker and I'm actually more comfortable on it. I sort of feel obligated in a way to represent its sound on the songs that were written around it. It's kind of nice to switch back and forth."

Lifeson uses several guitars, including one that looks a bit like a Schecter but is actually a heavily-customized Fender." It started out as a Strat," Lifeson explains, "but I made a couple of changes on it. It has a Shark neck, which is a company in Ottawa that makes the necks, no finish on it at all, it's just bare wood. It's a rosewood neck, a little flatter than a Fender, a Bill Lawrence 0500 and a custom plate. So really the only Fender thing left on it is the body, the actual body and the two Fender pickups.

"I've been using the same guitars for several years, a Howard Roberts and a 355, but I'm not going to change guitars just for the sake of changing a guitar. I don't find the sound differential that great and of the three I think the Fender sounds the best. It's got the warmth and fullness of a Gibson but it's got that top end clarity and brilliance of a Fender so it's really achieving what both guitars would do."

WITH THE BAND INCORPORATING keyboard synthesizers into its approach you might think that Lifeson was also working on guitar-triggered synthesizer effects, but he doesn't really like them. "We used one on Hemispheres," he recalls. "It was just such a headache. It was still new, had lots of problems, and we ended up dropping that song anyway. It was the first generation of guitar synthesizers, the Roland, and if you were in a hall that had a lot of RF interference the unit would pick it up; if it happened to be cold and damp the unit would pick it up. The sensitivity on the trigger one day would be okay and the next day would be bad. The tuning was bad.

"Apparently," Lee interjects, "the new units are a lot better. A guy brought in a real interesting unit today-it was a prototype, shaped like a guitar. It had these touch bars where the strings would be and there was this touch sensitive fretboard going into a digital synthesizer. You put your finger on the fret and you touch the bar that represented the string and it would make a sound."

"It takes a whole different technique to play an instrument like that," Lifeson agrees, "but it's definitely innovative. It has a future. You get some great sounds on it, and with the whole movement to digital on the synthesizers it's going to open up a lot of doors. I could see experimenting with an instrument like that. I'm pretty traditional in what I like soundwise, though. I like some basic effects like echo and chorus, phasing..."

Lifeson's solos are definitely high points in the band's sets, and a couple of the solos feature arranged effects. "The Body Electric" is particularly interesting. "That's the harmonizer set at just delay," explains Lifeson. "I think the delay is ten or twenty milliseconds, with the envelope really cranked up so that as the note drifts it decays gradually. If you play a number of notes in quick sequence you won't get that but as soon as you hold a note it drops down. That and some echo and some chorus. It's pretty bizarre."

Another great moment comes on "The Weapon." "Outside of the atmospherics at the beginning, I'm using an octave divider, a flanger, and echo with chorus. It's really in three parts, the middle part would be with the octave divider and the flanger. The last part is just some straight guitar with some Chorus."

During the nearly fifteen years Lifeson and Lee have been playing together they've seen musical trends change from hard rock to fusion to punk rock and beyond. The approach to guitar playing that has accompanied each of these shifts has affected Lifeson in such a way as to subtly alter the group's sound. "Over the years I certainly was affected by a lot of guitarists," he says, "more in an open way, a sort of stylistic change to...not copy, but get the same kind of feel as a lot of guitarists. Steve Hackett at the time we were doing Caress of Steel was a big influence on me. On that record there are a couple of solos that are very reminiscent of his style of playing with Genesis around that time. Later on I got into Allan Holdsworth, I got the whammy bar on the Strat and it was getting a little bit too close to that. Now I think I'm a little more influenced by guitarists like Edge in U2, the guitarist in Simple Minds, the way they approach playing guitar in the context of a band. I think I'm moving more in that direction, trying to incorporate more chordal changes, not just a flurry of notes."

Obviously, Lifeson feels that the heavy metal image attached to Rush is inappropriate. "I don't think we ever really considered ourselves a heavy metal band," he insists. "I think we thought more of ourselves as a hard rock band. We left a few doors open, although I certainly can't see a connection between us and renaissance heavy metal bands like Saxon. Our music has the power associated with heavy metal but that's only a part of it."

Perhaps the best explanation of the band's attitude towards heavy metal came, finally, from Lee. "I used to like the heavy metal bands," he recalls, "the first time that sound came around. I just think it's really pathetic this time around , and besides, our tastes are changing as we get older."

Rush, then, is the thinking person's heavy metal, a snifter of brandy for the veteran rocker who's outgrown the more shriekier sounds.