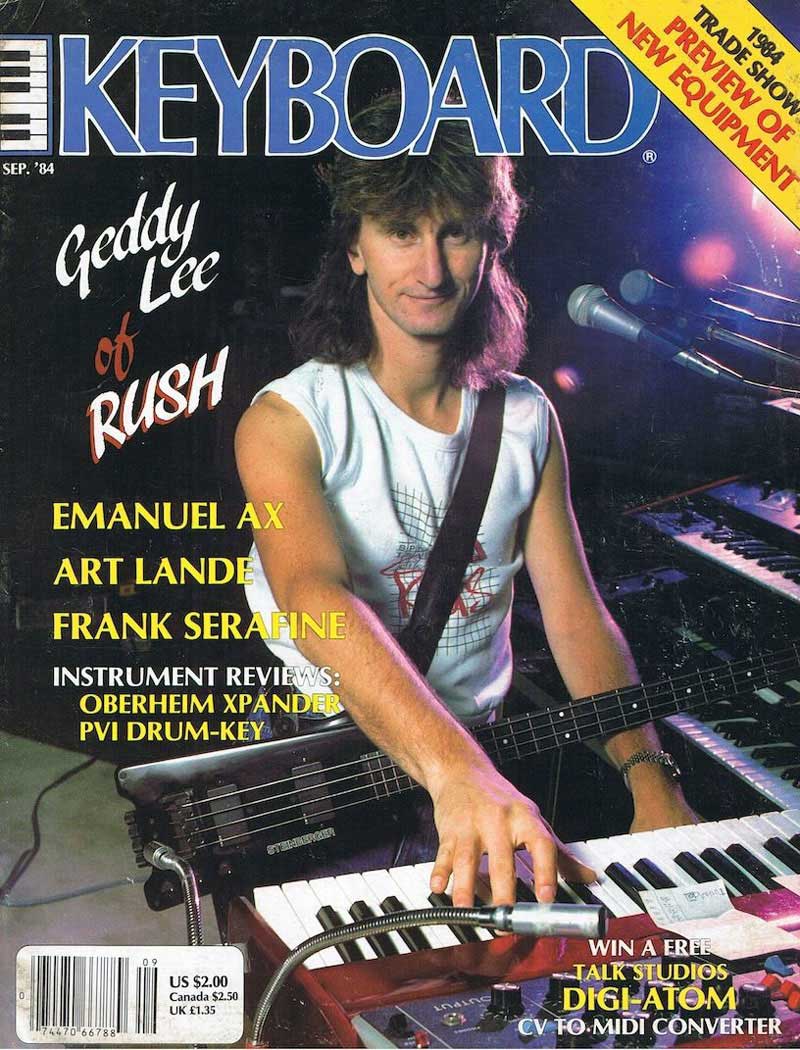

Geddy Lee Of Rush

By Greg Armbruster, Keyboard, September 1984

Laser light beams burst from the stage and arch across the auditorium, accompanied by a cresting wave of sound that physically staggers the tightly packed crowd beyond the security barricades. In response, the audience matches the music's momentum with a vast, arms-raised roaring benediction, which all but swallows Geddy Lee's high-pitched opening vocal. Lee, who also plays synthesizers and bass, guitarist Alex Lifeson, and drummer Neil Peart all seem to twist, jerk, and vibrate as if they themselves were electrified, generating a volume of sound that's palpable in its intensity. Like mythological elementals, melody, harmony, and rhythm become irresistible forces - swelling, surging, and exploding over the audience. This unrelenting music can literally blast all else from your mind and become the center of your consciousness; this is white-hot-from-the-furnace heavy metal rock and roll!

It seems impossible that there are only three mortal human beings at the center of this maelstrom, but then groups like Rush don't earn the title "power trio" without being able to stand in the eye of a musical hurricane. And when you have a power trio that's been fused together by the heat of their talents for more than ten years, the resulting alloy is strong and durable - characteristics of Rush's continued popularity in a style of music that boasts few enduring monuments.

Forged in Toronto in September 1968, Rush's original roster included Geddy, Alex, and drummer John Rutsey. With musical influences like Cream, Led Zeppelin, Procol Harum, the Who, and Jeff Beck, it's hard to believe that their sound could fit inside a local coffeehouse in the basement of a church. But they were Friday night regulars there until Ray Danniels heard their sound and asked to manage them. "He was sort of a local street-type, hustling kind of a guy," according to Geddy in his 1980 Guitar Player interview. Danniels started booking the band into Ontario high schools. When the drinking age in Toronto was lowered to 18, he was able to shift them into rock bars where they could be appreciated by an older crowd. However, their desire to play original material at high decibel levels severely curtailed their performance opportunities. So for six years the band paid its dues in small venues around Toronto, finally culminating in their first record, Rush, and a U.S. tour in 1974. It was just before this tour that Rutsey finally called it quits and was replaced by Neil Peart.

Then the real odyssey, encompassing eleven records and as many major tours, began in earnest. First opening for groups like Aerosmith, Kiss, and Blue Oyster Cult, then headlining their own tours, they continued to perfect their special blend of intricate, Zeppelin-like heavy rock for a growing audience of appreciative fans. An important metamorphosis of their sound came in 1977 with the release of Farewell to Kings, when Geddy Lee added synthesizers to the band's instrument arsenal. This change immediately expanded their textual capabilities, in the studio as well as onstage, and more than anything else inspired their musical growth in new directions and allowed their three-man sound to keep pace with the ever-increasing orchestrated complexity of progressive rock music.

Geddy's decision to play the synthesizers himself was not made quickly. After all, his responsibilities already included bass and lead vocals. But he had first played the piano as a child, long before picking up the bass in high school. "It was your basic suburban story," he remembers, "where you're very young and your mother thinks you should play the piano. I must have been nine or ten, and I remember going to lessons twice a week for a couple of years at the most. When I was really young, my sister took piano lessons and I was intrigued by the sounds. I was able to listen to the parts she was learning and figure them out by ear. I always trusted my ear, even when I was pretty young, and my ear has been my bread and butter." And when his ear dictated the need for another sound in the band, the synthesizer was the obvious choice. Also, it could be triggered from footpedals, which would allow him to continue playing bass at the same time. Of course, one synthesizer led to another, Alex joined Geddy on his own set of Moog Taurus pedals, and now a stack of keyboards rises from each side of the stage: electronic orchestral towers buttressing Rush's soaring musical architecture with load-bearing sound supports.

On their most recent record, Grace Under Pressure, and the accompanying tour, Geddy has taken another step forward with his keyboard playing. For the first time, the bass has come off the shoulder and he has revealed his growing talents as a multi-keyboardist, triggering pedals and sequence switches with his feet, and grabbing a multitude of sounds, lead lines, and bass runs with both hands.

Although guitar, bass, and drums are still the foundation, keyboards are playing an ever-greater role in Rush's musical epics. In fact, Geddy Lee scored high in our 1981 Keyboard Poll in the Best New Talent category. We talked with Geddy backstage just after a sold-out concert at the Cow Palace in South San Francisco. His soft-spoken articulate manner belied the monstrous sound within which he and his companions had so recently reveled onstage. His opinions about synthesizers and their use within the band show a remarkable understanding of keyboards in popular rock music and their importance in the continued success of Rush.

With all the keyboards that you play, do you now consider yourself more of a keyboard player than a bassist?

Well, it's funny; I still think of myself as a bassist, but I put more effort and more time into playing keyboards. Of all the instruments that I play at home, I end up playing keyboards more than anything because it's such a challenge. It's also more satisfying than playing bass on my own. Although I love playing bass, I'd rather play it *with* somebody - a bass is a lonely instrument on its own. But with keyboards, especially synthesizers, you can put up a sound and bathe yourself in it. Who needs anyone else? My actual ability on keyboards is somewhat limited, and I don't consider myself a keyboard player, although I do like playing the synthesizers. I look at myself as more of a melodic composer with the synthesizer. As a keyboard player I can't play a lot of complex chord changes or move through a very complex structure, but I can find lots and lots of melodies. I can write lots of songs on a synthesizer. I can zone in on the sound that I want and make it speak for the mood I want to create; that's my role as a synthesist.

Today, do you have to be a "keyboard player" to play keyboards?

Obviously not [laughs]. I find that more and more people who aren't accomplished musicians as keyboard players are synthesizer players, or synthesists. However, a guy who doesn't have any musicality is not going to make anything worthwhile. If you haven't got a musical sense or a musical feel, you can have all the toys in the world but you're still going to come up with nothing. What I believe in most as a musician is musical sense, or musicality, not how many notes you can play, or how many schools you've gone to. What can you do with the knowledge that you have? Some people with very limited technical knowledge can do amazing things - - they can speak musically. Actually, you can make music with very few notes. After all, there aren't that many notes to begin with.

Are your synthesizer solos composed or improvised?

I write those melodies. For any melody part I'll try to pick the right notes and the right pacing, just like I would write a vocal part. Those synthesizer breaks in "Xanadu" and "The Trees" [from Exit...Stage Left] I don't really think of as solos. I consider them melody bits or parts. The only real keyboard solo I think I ever played was the Minimoog lead on "Countdown" [from Signals] and I don't think I'll ever do that again. I do a little improvisation on keyboards, but not much. I stick to business with the keyboards.

What inspires your melodies when you sit down at the keyboard?

A lot times the sound inspires me. That's why I'm so in love with the PPG that I have now - it's almost like a magical instrument. It's got such a wide variety of interesting sounds. I prefer sounds that are like acoustic instruments but have something of their own; something undefinable. Whenever I stumble over one of those sounds, the melodies just pop out of me. As soon as I hear a sound and start playing around with it, things come to mind. Of all the instruments I've had, I think the PPG drives me the most to write.

What other features sold you on the PPG?

What I liked about the PPG was the fact that it was a digital *and* an analog synthesizer [digital oscillators with analog filters]. Mind you, there's nothing like an analog synthesizer when you want a powerful sound. Analog synthesizers like the Oberheim OB-Xa and the Roland JP-8 have an organic punch to them that I find difficult to get out of a digital synthesizer like the PPG. But they have their own unique areas where they shine. The PPG has a crystalline sound which sparkles. It has a very 'invisible' sort of sound that the guitar punches through very easily. I guess the structure of the wavetables and the combination of waveforms that go into making the wavetable and the digitized sound itself imparts a more 'transparent' quality to the sound. Analog synthesizers seem to be a little more 'sludgy' and soak up more space. I find it's harder to get that crystal clarity out of them. With the PPG, I can take a digital sound and apply all the standard analog techniques to it. The PPG is also very 'user-friendly,' as they say in the computer world. It's laid out very well - very applicable to the player. Some synthesizers are great for the studio, but not so practical for a performance. The PPG stands on its own as a performance synthesizer, and it can be used for sampling sounds in the studio like a Fairlight by adding the Waveterm. Although the composition page on the Fairlight is probably a lot more extensive, the PPG is developing in that area. Besides, I just love the sound of it; it really has inspiring sounds.

How do you go about looking for those unique, special sounds that inspire songs?

I usually start with some other sound that gets me going. When I'm in the studio, I'll go through a hundred sounds until find something that's a trigger for me. When I find something that's in the ballpark, I start playing with it; change the shape of the envelope, start changing the wavetable a bit. I play around with a lot of variations until I get the sound that moves me. Then, once I get a sound that's close, I start playing around with the acoustic environment, because how it's recorded is very important. When you put a synthesizer directly into a [mixing] board and then directly onto tape, the sound is not moving in the air and sounds sterile. For me, it's very important that it go through some sort of speaker. I like putting it through speakers and miking it. If you go direct, it sounds too close. I want to push it back a bit and hear it bouncing off some walls. It feels a little more like it's a person playing an instrument in a room. It's coming from some sort of environment instead of *blotto* - there it is. If you go direct, you have to use toys like reverb and chorus units. There's also a very interesting unit out now called the Quantec Room Simulator which puts the sound into a space where you can define the dimensions of a room. It's a pretty sophisticated toy, but putting the signal through a speaker in the studio and miking it works just as well.

Do you change the size of the speaker cabinets in order to alter the sound?

Yeah, on this album [Grace Under Pressure] we experimented a lot with small cabinets. Sometimes we put the synthesizers screaming loud through two big JBL monitors and miked them from twenty feet back. We used that effect on "The Enemy Within" for the melody parts.

Other than reverbs and chorus units, what other effects devices have you used?

I used a vocoder once, but I didn't have good success with it. I couldn't get it to work very well. I like to use effects, but not for their own sake. I'd rather be concerned with ideas rather than just effects. Ideas stand out, but if you need to use a toy to help accomplish or enhance that idea, then that's fine. To use a toy for its own sake, as aural candy, is fun sometimes; but if you've got a good idea, you don't have to junk it up with toys and effects. I'm not a guitar player and that's why I think that way. Guitar players all think the other way: Got to have effects and toys, and this, that, and the other thing.

Do you use your synthesizers much for sound effects?

Yes, especially on past albums there were always a few parts where it was strictly sound effects. There are a couple of moments on this record where the same thing happens. In one sound I use a combination of a plucked string with a breaking glass. Jim Burgess, who was helping me with the PPG programming, created this sound. I used it on "Red Lenses" to go along with the rhythm of the drums, which are playing a real accented part. On those accents, I would hit this sound. But when you hear it on the record you don't notice those two things individually, you just feel the effect. In "Afterimage" I used a combination of a vocal sound and a human voice and played a few random melodies that overlapped the main part, which created some emotional peaks and valleys. There's nothing like doing that spontaneously; I think that's part of the magic of making records. When you're playing a part with a sound that you love, almost anything you play sounds beautiful. Listening to a piece of music that's well structured and trying to spontaneously fit notes in to make your emotions rise, that's the magic of recording I love best.

Do you feel that same magic during the mixdown?

Yes, but mixdown is more painful. For me, the two really creative areas in making records are the bed-track stage and the mixdown. The bed-track stage is very exciting because we're human beings playing together and going for that magical take, where all of our performances come together. Mixing requires so much concentration, and you really have to take yourself out of the studio; you have to separate yourself from the song. It's always a battle for me because I'm so close to everything. I know every part of every instrument so intimately, and yet I have to act as if I've never heard those parts before. You have to have a fresh objective sense because now it's not just a bunch of parts, now it has to become a song on a record. I think a great record is one that's mixed to sound like it's finished. It could be no other way than the way you hear it. That's what we go for when we're mixing, and sometimes we're successful and sometimes we're not. If you can have enough strength to hang on to a song until you've gotten the most out of it, that's the key to mixing. You have to be determined not to say, "Well, it sounds okay; that's good enough." There has to be someone objective there, and that's why I don't think we could ever produce ourselves.

Had your former producer, Terry Brown, finally lost that objectivity?

For all intents and purposes, he was in the band; he was one of us, and that was great. We made a lot of great albums together, but ten records is a long time working with the same attitudes. Sometimes you have to have a radical change. Sometimes you have to shake yourself and make sure you're not falling asleep at the wheel, or falling into bad habits, or just taking the easy way out every time. You want to have some fresh input that says, "That's not good enough. Maybe it was last year, but not now. Why don't you try something different?" That's what we wanted, and that's why we changed producers. Finding Peter Henderson was a step in our development, but I think we'll still keep looking for different things from here on in. You have to have that freshness, that excitement. It's very easy to get complacent in what we do, and that's the real tragedy. At this stage, we'll do anything we can to avoid that.

After eleven albums, haven't you pretty well defined the Rush sound?

It's a sound that's always in a state of flux. Every once in a while we reach a point where we solidify all the experiments. The 2112 album was the first solidification and Moving Pictures was the second. There always seems to be a transitional period before we assimilate everything. Neil [Peart] thinks that Grace Under Pressure is another solidification point, but I don't agree with him. I think we're still on the way to some other place. Then again, right after each record I feel like it was close; that we're getting closer to the record that's still in us. That's good, though, because that means we're still caring and we still want to do it.

Isn't there a problem sometimes transferring a fresh studio sound or a new musical direction to the stage?

Yeah, sometimes you have to hold back in the studio. If you have the PPG and the Waveterm [digital sampling], you're so limitless in the studio. You can put in so many sounds that you don't really hear and you're not really aware of, but they subtly evoke a mood. They're all part of the overall sound and mood of the song. In the studio you do that with four, five, six, or seven different tracks. Onstage it's just you and your instruments; you don't have any tracks. So you have to have a sound that speaks for all of those subtle studio sounds in a different way, and that's difficult to do. That's probably the only frustrating thing about making records. Because we're a live band we sometimes have to draw a line. And in a sense, maybe that's good, because it keeps our music from being over-produced. Sometimes we'd like to be able to just go nuts on something, and from time to time we'll do a song in the studio that we agree not to do onstage. We'll never play it live, so let's go and have some fun. Of course, if you write something that's that good, you want to play it live if it turns out well. We're doing a song on this tour called "Witch Hunt" that was originally written as a studio song. We wouldn't play it live because we wanted to be able to add extra keyboards and other things. We felt that we could never reproduce it live so we never played it. Then just on a whim, we tried it in rehearsal and it sounded fine. We'd grown so much since writing it and had acquired all these new keyboards that it works now.

What synthesizer did you start with, and how did you first use it with the band?

The first thing I got was a Moog Taurus, then a Minimoog, and it all grew from there. I got the Taurus because I wanted to play double-neck guitar, and I wanted to keep the bass going while I backed up Alex [Lifeson] on rhythm guitar. When I picked up the Minimoog and started plunking around on it, I realized it required a different attitude to write with it. I started writing melodies on it, like the "Farewell To Kings" intro, and my music began to evolve. On Farewell To Kings I used a little bit of Minimoog and Taurus pedals just to have another sound besides guitar, bass, and drums. It was so refreshing to add a texture that we could drone behind our sound - we didn't use it blatantly. That feeling and pulse in the background was really how it started. Then when we went to a very tight three-piece, it didn't feel so dry and empty. But as I started getting more and more keyboards, I started writing more on them, which was a big difference from our earlier material. A lot of the songs we do today were written on keyboards.

Can you trace the path of keyboard influence in you albums?

I guess Farewell To Kings was the first one, where we used the synthesizers for string washes and texture fills. By the time we did Hemispheres I had added an Oberheim Eight-Voice. That's when I really started to get keyboard crazy. "Truths" from Hemispheres and "Camera Eye" from Moving Pictures were both written on keyboards. With "Spirit Of Radio" and "Natural Science" from Permanent Waves, I started using a lot of sequences. I wrote those little melodies on keyboard and wrote the bass and guitar lines to fit the sequences. "Subdivisions", "Chemistry", and "The Weapon" [from Signals] were entirely written on keyboards. After Signals we realized that we had gotten so keyboard-heavy that Alex was getting frustrated as a guitarist. His role had been relegated to fundamental parts a lot of times because the keyboards were so dominant. So with our latest album, Grace Under Pressure, we transposed the parts I wrote on keyboards for the the guitar, and I went back to the bass. As a result, a song that started on keyboards ended up with no keyboards in it, or at least for part of it. That helped put the guitar back in the proper perspective for our band and yet still utilized the keyboards in a more subtle musical way. Also on this album, we put a lot of time and thought into experimenting with the kinds of sounds we wanted. We tried to find sounds that had a different character and [frequency] range than those of the guitar. That was part of the problem with Signals: The guitar and keyboards were sharing the same range too much, and it was a struggle. They were each fighting for their fair share of sound.

Do you mean range not only in terms of notes but in sound and texture as well?

Absolutely; especially with a sound like ours, where three very busy players are trying to put in a lot. Somehow our sounds have to be pushed apart from each other in order to hear them, otherwise it just becomes this mess of midrange. With Grace Under Pressure, I tried to move the keyboards out of the guitar range on every track. I tried to let the guitar be natural and breathe, and at the same time find something for the synthesizer sound that had character and was unique. But there's so much good synthesizer music around today that it's very hard not to use synthesizer cliches.

Which synthesists do you listen to?

The Fixx and Tears For Rears; they make really synthesized records. Almost everything in them is synthesized in some way or another. Peter Gabriel and Larry Fast have some pretty high-quality stuff that's state-of-the-art. I also listen to Simple Minds, Ultravox, Talk Talk, the Eurythmics, and Kind Sunny Ade. Lately, I've been listening to Howard Jones' Human's Lib [Electra, 60346-1]. I think it's a real contemporary record, keyboardwise and vocally. I like the new King Crimson album [Three Of A Perfect Pair, Warner Bros., 1-25071]. When you have musicians like these educating people, discovering sounds, and utilizing new techniques, it really sets the pace for synthesizer players. I feel that I can't just go into the studio and use some token sound. A lot of thought should be given to try to find new sounds that are fresh and different.

Are you a self-taught synthesist?

Yeah, but a friend of mine, Terry Watkinson, who was a keyboard player for a group called Max Webster, used to sit down with me and explain the fundamentals. He used to draw little charts for me; he was like a tutor I had on the road. He did a whole tour with us and I picked up tips about playing keyboards. At that time, I had one of the first Oberheim Eight-Voices with the different modules; it was huge! But before I brought it into the band, I used to have it set up every night in a tuning room backstage. I used to play with it and try to figure out some of the fundamentals of synthesis. As far as the mechanics of playing keyboards, I had played the piano years and years ago but I'd forgotten everything about it. So I had to learn all over again and try to figure out what to do. Since I learned over again on a synthesizer, I have a real difficulty playing piano because now I'm used to the spring-action keyboard. Playing piano is a lot more disciplined than synthesizer playing. If you have a strong sense melody and some musicality you can get away with a lot more playing a synthesizer than you can playing a piano. You can't just scoot by on a piano. It's a demanding instrument and you have to make the thing work. On a synthesizer, the sound can have a feel. It's so electronic that all you have to do to make it live is apply some musicality and write the melody.

But you still had to develop some keyboard technique in order to play the synthesizer onstage. How did you improve your abilities?

It was through practice and writing. I try to write things that are more difficult for me to play. With Grace Under Pressure I tried to write moving bass parts that were independent of the right-hand parts. So in my own way, I'm working very hard to develop my right/left independence, with a lot more movement in my left hand. You see, playing the bass is different because you're in sync. Although your hands are doing different things, rhythmically they're in sync. Whereas, the difficult thing about playing keyboards is the rhythmically you have to be out of sync, or independent. Also, I have to look opposite ways. My first tendency when I started playing keyboards was every time my right hand went down, my left hand went down. As a result, all my parts were together. And even though I've gotten my right hand to the point where I can make a lot of chord changes and do that pretty smoothly, I'm still working on my left hand. Trying to get it to work in the "holes," or independently, while the right hand does whatever.

Have you ever considered imitating the physical freedom you have with the bass by playing a remote keyboard?

That rubs me the wrong way. I think it looks like hell when those guys walk around with keyboards. It looks 'Las Vegas' to me. The only guy who had one that looked pretty decent was Roger Powell from Utopia. He looked believable. He also plays like a maniac, which helps, and I like him a lot. He's real good.

In order to improve your technique, do you make it a point to write beyond your ability to play?

I think you have to - that's how you get better. In the earlier days, around Hemispheres time, we always did that. I'd write a part and go, "Wow! This is tough to play." We would have to play it a lot in order to play it well. During this period that was all we had to do: Figure out something that was hard to play and in an odd time signature. We would write fourteen different pieces, or bits, that were in different time signatures and stick them all together to create a concept. That was all well and good for the time, but in a certain sense, it was really an easy way out. Okay, it wasn't easy to play and it wasn't easy to think of, but it was easier than trying to write a great song that's got a lasting melody and a moving feel. Now, because our technical ability has gotten to a point where we can pretty well play anything we can think of, our focus has shifted so that feel is becoming more important than a melody, or the use of melodies and their combination. Now we're using simpler rhythmic formats and shading the melodies with the keyboards. We've become more fascinate with this sort of classic structure.

What do you mean by classic structure? Classical music forms?

Not in the sense of classical music, but classical in the sense of a classic rock song. Two things make a great memorable song: feel and melody - how that song hits you and the melody that it leaves you with. We're in the pursuit of that, and at the same time we're trying not to sacrifice the technical chops that we've gotten together. That's what makes it difficult. Sometimes I think we interrupt a great feel by throwing in some busy bit of business because we can't play anything that's too simple for too long - we start getting hyper. It's been said that we have a hyperactive rhythm section and I think it's true, but there's nothing we can do about it. We have to play like that because it's really us. Sometimes it might suit the song for us to calm down a bit and let the thing just ride, but boredom sets in and that's it. You've got to play something. Maybe that's our bane; maybe that's the one thing that will keep us back from making the ultimate song or album that we feel is in us.

Isn't a "classical rock" song a contradiction in terms?

There have been great meetings of those two extremes. I'm a big believer in fusing these styles. That's why a lot of rock and roll purists hate what we do, because it's all fusion - we'll use anything and I don't care where the influence comes from. We've taken a very symphonic approach to some of our songs in the past. It's one thing for me to say cynically that a lot of our earlier pieces were just "sticking things together," but in our own way we were orchestrating. We were taking that symphonic attitude or using that structure. Now we're trying to do it on a shorter, more immediate scale, because we seem to be going through a period of music where the communication has to be more direct. And we want to remain a band that communicates something. It's all well and good to write whatever kind of music you feel like writing, but at the same time you want to communicate. That's what music is all about. For me, music is two things: It's my expression , and it's my willingness to communicate, or convey that expression. If you just care about the first part of the equation, that you're going to express what you want to express and everyone be damned, then it doesn't matter what kind of music you write. It doesn't matter what you're expressing in what style. But if you care about the second part of the equation, which is wanting to communicate that expression to somebody out there, then yes, you have to be concerned with the language of the day. And I think that people today want, or need, or are having a more direct kind of communication. So we're trying to apply all these things that we've learned over the years in a more direct way so that we're not just talking to ourselves.

Doesn't this musical responsibility to your audience inhibit your writing somewhat?

No, I don't think so. It's a real challenge for me to be able to put what we want to express across in a contemporary vein. We're going through a period of music where it almost has to be felt more than heard. It seems to be almost more sensory than it is cerebral. It's a very direct, spontaneous time, and I don't know if much of the music that's being made today will be remembered, or if it will be regarded as well-constructed music. I don't think much of rock will shine through and survive like classical music does, because rock is popular music - pop music. Classical music has depth and lasting ability. I don't think pop music does, because it's so much a reflection of the times.

And classical music wasn't?

I don't think so; not in the sense that it's dated. If you listen to a piece of classical music, it's a piece of *music*. But if you listen to a pop song from 1954, it sounds like a pop song from 1954. Who knows how much of the music that's being written today will be worth listening to in ten years, except for nostalgia? And that's the way pop music seems to get categorized. We're listening to nostalgia songs now, ones that I grew up with. They lasted, but only in a real sentimental way, not in a classic sense of music to be revered like classical music is. Maybe some the longer pieces or some of the more serious pieces of music for the mid-'70s will be remembered as great pieces of music. Also in the mid-'70s, it seemed that people were listening to music more than they are now. There were longer pieces being written and people would close their eyes and get inside the tune. People had more patience for a song and would let the song develop. But now, rhythmically and melodically, it has to be very immediate, and the depth comes from the textural structure.

So today, isn't the role of synthesizers in the Rush sound still one of defining background textures and evoking moods?

They have forced their way into becoming a very integral part of our sound. And at times their role is to enhance a fundamental three-piece sound. But at other times they come to the forefront -theirs must be the primary sound. I think that's what gives variety to our sound and also adds some freshness. I don't think any of us are content to be a guitar-oriented band any more; not with all the music that's going on now and with all the refreshing sounds that are being made. There are real pioneers in rock music today. Peter Gabriel's Security [Geffen Records, GHS-2011] is a perfect example. When you listen to that kind of record and get inspired by what can be done, then you can't really be satisfied with something that isn't keeping up. That's the way we feel about it. As much as we want to remain a three-piece, we would like to move into the areas of exploration that other people are moving into. It's hard to hold yourself back, and I think as musicians, it's wrong to hold yourself back. Synthesizers have abridged a gap and opened up an area for us. They have taken us from a strictly three-piece hard rock band to a band that speaks in the language of today, which I think is real important. The musical language of today is rhythmic immediacy, melodic strength, and textural depth. And the texture, the shading and coloring, is what makes you want to hear it more and more.

Are lyrics that necessary, then?

I think so, because they are the point of the statement - the focus. That's what gives the song meaning. That's what separates it from just being rambling, although I think you can make a statement without words. With words, it brings another level to the song. It's the final communication.

Just as sounds suggest melodies, do the melodies suggest words?

Sometimes, but more often than not, my job is to draw some sort of musical mood out of a lyric. Usually I'm orchestrating lyrics that are already written. However, with a song like "Between The Wheels" [from Grace Under Pressure], we came into the rehearsal studio and I started playing. The whole song came out in about twenty minutes. We all started jamming and it became a song accidentally, or spontaneously, and then the lyrics were written. In that case, the chords that I stumbled onto, and the jamming that followed, were so emotive that they inspired Neil [Peart] to write the words. On the other hand, the lyrics for "Afterimage" were already written. They were very personal and it was very important that the right notes, the right melody, be found. That was a case of writing strictly to the lyric, and by the way, that song was written mostly on keyboards.

Does your high vocal range often determine the key in which the music is written?

Well, it used to be an afterthought, and I would get into a lot trouble because after we wrote the song and I would go to sing it, I would realize that I could only sing it very high or very low -nothing in the middle would work. Hemispheres was an example of that. The whole record was written in a very difficult key for me to sing If I sang low, I didn't have any power, so I had to sing way up high, and it's difficult to do. That's partly how I go my reputation as a 'high singing guy'.

You don't sing as high any more, do you?

No, and that's a conscious decision, because I want to use my voice more. I want to sing more, and it's real hard to sing when you're using all your energy to stay two octaves above mortal man. It's a lot of work to keep punching your voice up. Besides, I think my voice has a much better sound in my natural speaking range, and it's a lot more enjoyable to sing. I can actually close my eyes and just use my voice and sing; I love it.

Because you've been together so long, do you feel that Alex and Neil have become extensions of your orchestral inspirations?

Sometimes it's that way, and sometimes the drum part is so strong that it evokes something for Alex and me. Sometimes the guitar part is the drive; it really goes three ways - there's really not one musical leader. I guess because I play bass and keyboards, and sing, a lot of the inspiration for writing our songs comes from me, partly because I have so much to do, partly because I have a vested interest in almost every aspect of the song, and partly because of my nature - I'm more of a workaholic than my partners. However, it's remarkably a three-way division, a democracy, and I think in terms of me as part of a band. A lot of times when I'm writing a song, I'll write my part bearing in mind that Alex will have his part too. I don't try to complete the thing. I'll leave holes for Alex to inject his ideas, like he does for me.

How do you practice in order to do three different things on stage: bass, keyboards, and vocals?

Well, I practice in bits and pieces. At home I like to have all my keyboards set up like I have them live, so that when I start to work on stuff, I can practice all the motions. The majority of my practice is with the other members of the band. When we're working on a song in the studio, we work on it for a long time. That rehearsal period really gets my chops together. As a musician that plays more than one instrument, one thing that helps me is to try to keep the melodic thread in common with keyboards, vocals, and bass. If I'm playing bass to a keyboard part and a vocal line, I'll try to make them have some kind of connection in my head to the vocal. If I'm singing one thing through a bass change, a keyboard change, and a bass pedal change, I try to make those relate in some way to the vocal part, whether it's rhythmically or melodically. Then it's an easier transition, and I don't have to be three different people at the same time. You can have that independence, but for me it works if there is some sort of common thread within it. In the end I think it helps give the song a unifying melody. I know it's helped my bass playing. A long time ago, I found it difficult to sing and play bass at the same time, so I started making my bass parts more melodic, which gave them something more in common with my singing. This helped make my bass patterns more musical instead of just fundamental roots. It also made my bass playing busier, which I liked [laughs].

In order to coordinate all your instrumental playing with your vocals, you have to know exactly where you are at all times when you're performing. Doesn't thins precise choreography inhibit your musical spontaneity?

It does sometimes, because you have to be aware of that choreography a lot on stage. Many times towards the end of one song, I'll have to be thinking about what my setups are for the next song. Whenever I have a breathing space, I flick a switch, or put up a patch, or step on a button, or change a dial, and it does take away from the spontaneity of my playing. In the PPG I've got all my sounds stepped, so that all I have to do is step on a pedal and my next sound is there. That's such a relief because I don't have to think about it. But with the other instruments, there are a lot of changes to be made, and I can't totally put myself in a musician frame of mind. I can't totally just play for the whole song. At some point, I have to snap myself back to reality and think about the setup for the next song. Otherwise, I'd be forever between each tune. I'd have to say, "Excuse me, I'll be with you in about five minutes. I have to throw four hundred switches here." So I sacrifice total musical spontaneity in order to have a smooth and quick-paced show.

How do you synchronize your timing with the sequences?

Making sure you have the right momentary on/off switches. It's very important that the sequencer turns on when you step down and not when you lift your foot off. This sounds like a silly problem, but it's a very serious problem when your hands are full and you're using your feet to trigger very complex parts. It has to be right on or it blows the song. We found that a lot of momentary switches trigger on the way up, and they would always be out of sync. We couldn't figure out why, because I knew I was stepping on the foot pedal at the right time. Anyway, we had them all reversed so that as soon as they go down, they're on. Neil wears headphones when we're sequencing so he can play to the sequencer. The [Oberheim] DSXs are pretty solid; the control track keeps their temp the same all the time. So as long as Neil can hear that, we'll be in sync. The [Roland] TR-808 is the master clock when I'm just using the arpeggiator on the JP-8. Because it's such a busy thing, I will send Neil a click from the 808; the same click that's pulsing the arpeggiator will go to his headphones. So when I'm using a complex-arpeggiator part, he doesn't get all that running around. He gets the fundamental and syncs to that. It's a complex setup for him but it works.

When you start a song can you tell if the tempo is going to be right when the sequencer comes in?

Sometimes you know when you're right out to lunch, too! Sometimes the sequencer part comes in and, "Whoa, pull back on the reins here." Occasionally we're too slow; it can vary. We're human beings, and it depends on what we've been eating or how fired up we are. But Neil works real hard on making sure his tempos are steady and there's very rarely a problem of being out of sync. Some songs aren't much of a problem because there's so much sequencer. If the sequencer starts the song, the tempo is established right away and we're pretty well locked. But songs like "The Body Electric" [from Grace Under Pressure], where the sequencers only come in for the choruses, you have to make sure that you're playing the right tempo to begin with.

How do you use your arpeggiators?

I usually use the arpeggiator for hypnotic bass lines. On "Red Sector A" [from Grace Under Pressure] I use it very fast so that it has a real hypnotic pulse. I also use it in "The Weapon" [from Signals] for a repeating bass line. I think the arpeggiator is a great rhythmic tool. By using a real 'bottomy' sound, with Neil playing charge behind it, all of a sudden it's a real great groove.

You mentioned earlier that you've been working on left/right hand independence by writing keyboard bass lines for your left hand. Do you still rely on the arpeggiator or sequencer to play them for you onstage?

No, when I'm not playing bass, I play the bass lines on the keyboard now. For "Afterimage," I play all the bass lines in the left hand, and for "Between The Wheels" [also from Grace Under Pressure], I play most of the bass lines on keyboards. This was the big step for me on Grace Under Pressure as far as keyboard playing. Almost every time I had a right-hand keyboard part, I would write a bass pattern for the left hand, even if it was basic, just to get into the habit of doing it. That way I could set up different bass sounds too. On this tour I've been using two keyboards at the same time, and I've never done that before. That's all part of the development of my hand independence. I can set up one sound here and set up the bass sound there and go for it. It's a nice feeling to have those sounds spread out like that.

As you've gotten better on keyboards, have you considered making a solo album?

Someday I'll do one, but I think it will be more of an album with other people I've wanted to play with for a long time rather than, "Ta da! Here's Geddy Lee and what he really does!" I'm not a big believer in guys who do solo albums just to strut their personal stuff. The only reason I'll do a 'solo' album would be to use my position to make record with musicians that I know and respect and would love to play with but don't get the chance. Mostly friends of mine at home, like [violinist] Ben Mink [who played on "Losing It" from Signals], or [keyboardist] Hugh Syme [Who played piano on "Different Strings" from Permanent Waves, and has been the art director for all the Rush album covers]. But generally everything that I want to do musically I can do in Rush, so I'm not frustrated. I don't have fourteen songs put aside. Everytime I save something for myself, it gets used in the band anyway.

Is there anything in your musical career that you would do differently?

The only thing I would do is learn a little more about the language of music. I would like to have learned earlier about writing music and knowing the written notes of the bass at a younger age. I learned all those things late in life. I don't think it's a necessity but it's a definite advantage, especially when you communicate with other musicians. It was never that important to me because I was in a band with the same people for many, many years, so we developed our own way of talking to each other. When I first started communicating with other musicians, I realized how little I knew, and it was a real hindrance and a disadvantage.

How would you sum up your musical experiences and advise younger players?

Well, I think as long as you're honest with yourself about whatever you do, then the one thing that will shine through is how much conviction goes into the piece that you're playing or writing. I think people know when somebody means it and when they don't And often that's the difference between me liking a piece of music or not liking it. If you know that someone really believes in what they're doing and is putting it across, then it reaches a little farther. Be honest with yourself and with whatever you're trying to communicate - that's the best form of expression. And my most important piece of advice for young musicians is...always take your wallet onstage with you.

On The Road With Rush: Tony Geranios, Synthesizer Technician

Self-taught musicians abound, but self-taught synthesizer technicians are exceptions in a field which is constantly expanding and calls for skills ranging from wire-soldering to computer programming. Tony Geranios, guitar and synthesizer maintenance expert for Rush, has learned his trade on the road, picking up tips and service expertise directly from the manufacturers' technicians. "That's the best place to learn it," he agrees. "You can learn whatever you want in a teaching situation or on paper, but when it actually comes to putting it to use, there are a lot of things that don't apply in a real life situation. I've tried to maintain as much communication as I can with all of the technicians at all of the companies that have to do with my equipment."

Before joining Rush's technical staff in August 1977, Tony briefly maintained the keyboards and guitars for Blue Oyster Cult. He had replaced the previous tech on a recommendation from the Cult's sound engineer, his brother George Geranios. "I was new on their crew when Rush started opening for Blue Oyster Cult," Tony remembers. "I had a much bigger keyboard rig with the Cult, but it was very basic analog stuff. I had always worked with Moog equipment so I knew a lot about it. They also had an L-5 Steinway piano that I learned how to tune and service, and a [Hammond] B-3 organ, which I beefed up. Actually, my brother taught me a lot of stuff. His influence was very important. At that time, he was utilizing an Oberheim module, which came from their Four-Voice modular system. He had interfaced it with the snare drum channel on his Midas mixing console and processed the signal through it, creating a very interesting drum solo effect that went along with the laser light show. I thought to myself, if you can take a control voltage from just the sound of a drum and alter it, why can't I trigger other synthesizers with one control voltage? So when I left the Cult and went to work for Rush, I wanted to develop a system where Geddy could play the [Moog Taurus] bass pedals and trigger other synthesizers."

Tony and Geddy finally solved the bass pedal/synthesizer interface problem when Rush toured with Bob Seger. "I knew Seger's old keyboard player, Robyn Robbins, who had just gotten an Oberheim Four-Voice. One afternoon during the sound check, he showed Geddy what was happening with it and then we started looking into that synthesizer for the bass pedal interface. At the time it was the only synthesizer that had a split keyboard capability, and Geddy wanted to play the lower half of the keyboard with the bass pedals and the upper half with his hand. Also, you could individually tune each module. You could have a horn sound on one module, a string sound on another, a wind sound on a third, and you could have different types of decay, all mixed into one total sound. With a lot of the newer keyboards you can't give distinctive characteristics to an individual module without some sort of computer memory involved. So Geddy ended up with an Oberheim Eight-Voice. It was a white elephant, but it worked, and it was very interesting."

Today, Tony has to take care of Geddy's synthesizer stack and guitarist Alex Lifeson's keyboard rig as well. "Geddy has a PPG Wave 2.2 with the Waveterm digital sampling option, a Minimoog, an OB-Xa with a DSX [sequencer], a [Roland] Jupiter-8, and a TR-808 drum machine connected to the arpeggiator of the Jupiter-8," Tony reports. "He also has two sets of Taurus bass pedals, one underneath the PPG and the other at the front mike location. When he depresses a pedal, he not only gets the bass pedal sound itself, he also gets the program that's up on the OB-Xa. He can play two synthesizers at the same time with just his feet! in addition, I've put switches on the bass pedals which allow Geddy to choose one of three octaves on the OB-Xa that the pedals will trigger. He can use the lower octave, the middle octave, or the top octave of the keyboard. Alex has two 120-program OB-Xas with two DSXs. One of the OB-Xas is interfaced with a set of bass pedals like Geddy's setup, and the other just plays sequences triggered from a remote pedal."

Even drummer Neil Peart has recently gone electric with a set of Simmons drums. "Neil has just gotten into things you plug in as opposed to things you just set up and hit," Tony remarks. "In fact, the only thing we use the TR-808 drum machine for is to trigger the arpeggiator on the Jupiter-8 and send a metronome reference click to Neil's headphones."

In the future, Tony has plans to incorporate comprehensive computer control over all of the synthesizers, binding them together into one integrated network. "I want to find a digital mainframe that we can use between the pedals and the synthesizers, that will give us program and preset capabilities," Tony reveals. "It could be preprogrammed for selected keyboards so that you could assign different notes, up to 18 different VCOs, to those keyboards, by depressing just one of the bass pedals. It would allow Geddy to have an entire chord with various strings and horns mixed in, each with different attack and decay times. This way one synthesizer could be used just for strings and another just for horns, and so on. That technology is around, it's just a matter of pulling it into the music world. The music industry is a very small part of anything that has to do with really sophisticated electronics - it's a very small piece of the pie. Video, movies, and big industries use a lot more computer mainframes and software than the music industry does. I want to have sophisticated interfacing capabilities, with real-time as well as preprogrammed functions, and a scratch-pad memory in our future computer interface system."

When asked to what extent the limitations of Geddy's instruments determine the character or orchestration of a particular song, Tony replies, "Well, they're all very careful in the studio not to overproduce themselves. They won't put on a lot of layers or tracks that they can't possibly come up with live. I've always instigated hardware changes, like the interfaces we have now, and I suggest to Geddy what the capabilities are, especially in the areas that I happen to be excited about on a day-to-day basis. If he sees something that would be useful, we'll get down and discuss ways of doing it. And if I can get this computer interface system together, then I'll feel very satisfied that I've done just about everything that I could do to further the possibilities of Rush's sound, in the studio and on the stage."