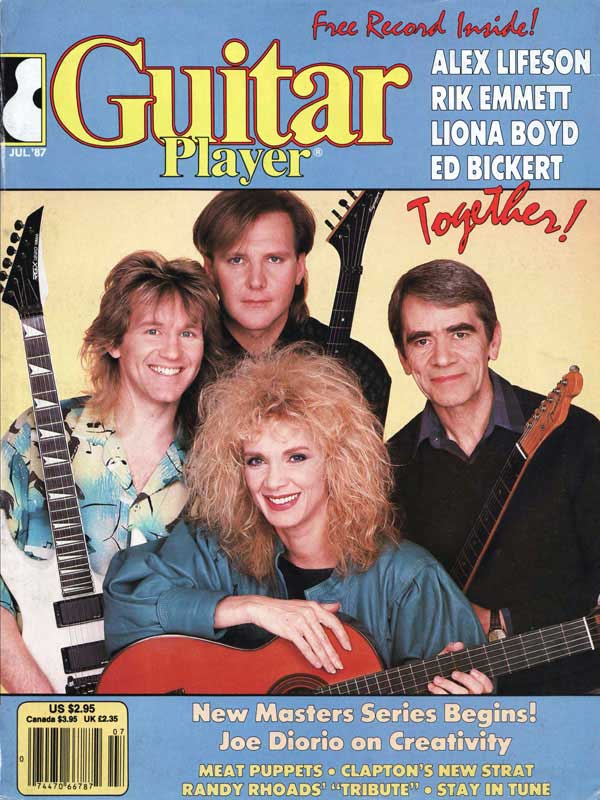

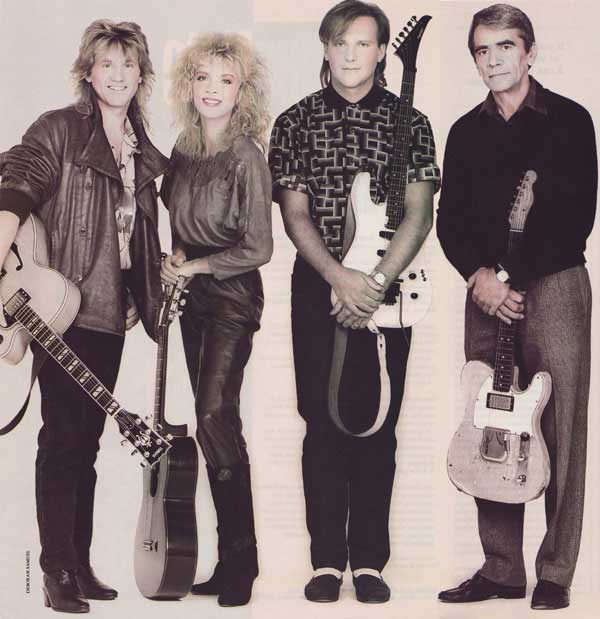

Canadian Guitar Summit

By Jim Ferguson, Guitar Player, July 1987, transcribed by pwrwindows

A SELECTED RIK EMMETT DISCOGRAPHY

With Triumph: Triumph, Attic (Canadian import), LA T 1012; Rock & Roll Machine, RCA, AFLI-2982; Just A Game, RCA, AFLI-3224; Progressions Of Power, RCA, AFLI-3524; Allied Forces, RCA, AFLI-3902; Never Surrender, Polygram, PDS-I-6345; Thunder Seven, MCA, 5537; Stages, MCA, 2-8020. With others: Diane Heatherington, Heatherington Rocks, Epic, PEC-80046; Justin Paige, Justin Paige, Capitol/ EMI, SKAO 6419.

A SELECTED ALEX LIFESON DISCOGRAPHY

With Rush (all on Mercury): Rush, SRM-l-IOOI ; Fly By Night, SRM- l-1023; Caress Of Steel, SRM-I-I046; 2112, SRM-I-I079; All The World's A Stage, SRM-2-7058; A Farewell To Kings, SRM-I-1184; Hemispheres, SRM-I-3743; Archives (re-release of Rush, Fly By Night, and Caress Of Steel), SRM-3-9200; Permanent Waves, SRM-I-4001; Exit, Stage Left, SRM-2-7001; Moving Pictures, SRM-I-4013; Signals, SRM-l-4063; Grace Under Pressure, 818476-1; Power Windows, 826098-1. With others: Platinum Blonde, Alien Shores, Epic, BFE-40147.

A SELECTED LIONA BOYD DISCOGRAPHY

Solo albums: Liona Boyd, Boot (Canadian import), BMC-3006; Liona Live In Tokyo, CBS, 1M 39031; The Best Of Liona Boyd, Columbia, FM-37788; Guitar For Christmas, Columbia, FM-37248. The Romantic Guitar Of Liona Boyd, CBS, 42016; Persona, CBS, 42120.

A SELECTED ED BICKERT DISCOGRAPHY

Solo albums: Ed Bickert, PM (20 Martha St., Woodcliff Lake, NJ 07657), PM 10 I; I Like To Recognize The Tune, United Artists, UALA 747G; At Toronto's Bourbon St., Concord (Box 845, Concord, CA94522), CJ-216; Bye Bye Baby, Concord, CJ-232; I Wished On The Moon, Concord, CJ-284. With Paul Desmond: Pure Desmond, CTI, 6059; The Paul Desmond Quartet Live, A&M Horizon, SP 850.

RIK EMMETT

LIONA BOYD

ALEX LIFESON

ED BICKERT

Fusing different musical forms is hardly new in the guitar world: The marriage between jazz and rock has survived nearly two decades, while jazz and classical get together fairly often. Of course, the more styles you try to blend, the less probable success becomes and the greater the risk of producing something whose sum is smaller than each individual element.

Rik Emmett, leader of the rock power trio Triumph and the author of Guitar Player's Back To Basics column, was fully aware of the artistic hazards involved when he proposed a Sound page recording to Editor Tom Wheeler in late 1986 that would fuse rock, jazz, and classical. While such a project promised to be the most complex one of its nature since the Sound page's debut in the Oct. '84 issue, after hearing Emmett's concept and who he had in mind to fill out his guitar quartet-Alex Lifeson, Liona Boyd, and Ed Bickert-the go-ahead was given.

The resulting composition-Emmett's masterful "Beyond Borders" -succeeds in melding its various elements on a number of levels. Although brilliant playing abounds, the piece is more than a vehicle for virtuosic displays as it integrates various styles and weaves in and out of different moods, textures, tones, rhythms, key centers, and time changes. The players receive ample solo space; however, the emphasis clearly is on interaction-a surprising outcome, considering the ever-present temptation to fall back on excessive blowing (Emmett discusses "Beyond Borders" on page 80; the Sound page and musical excerpts are on page 82).

While Emmett, Boyd, Lifeson, and Bickert reside in the greater-Toronto area of Canada's province of Ontario, each is a world-class artist whose abilities transcend national boundaries. Often referred to as "the first lady of the guitar," Liona Boyd early on earned a reputation as a fine classical artist. Always seeking new avenues of self-expression, she recently has explored more pop-oriented ensemble formats. Alex Lifeson is the dynamic guitarist for Rush, one of rock's most respected progressive units, while jazzer Ed Bickert's understated solos and sophisticated approach to chordal accompaniment have graced performances by luminaries such as saxophonist Paul Desmond, vibraphonist Milt Jackson, and trumpeter Ruby Braff. No stranger to Guitar Player's readers, Emmett directed the project; "Beyond Boundaries" was recorded at Triumph's Metalworks studio in Mississauga, Ontario. (For previous Guitar Player articles on Emmett, Lifeson, Boyd, and Bickert, see Crosscheck on page 179.)

Why were four prominent artists so eager to dedicate hours of valuable time to a noncommercial project of this magnitude? Rik Emmett says it all: "Everyone got involved out of their love for the guitar and music; it was as simple as that." In the following interview, the quartet discusses musical purism, what they learned from working with each other, their reservations about such a project, and who among them is the best guitarist.

What made you want to take time from your busy schedules to get involved in this project?

Rik Emmett: I've wanted to do something like this for a long time. It was an opportunity to get outside of the genre I'm usually known for, and it also gave me the opportunity to work with artists of such high caliber and stature. Some ofthe pieces I've done with Triumph blend a variety of styles, but I'm not good enough technically to do certain things-especially in Ed's and Liona's areas. It was great to be able to ask myself what I would do if I could write a part for a great player.

Alex Lifeson: When you work in a band like Rik and I do, you get used to playing in a certain way and having a certain attitude ' towards writing and performing. But when you do something like this with other musicians-especially ones who represent a broad musical scope-it gives you a lot of freedom to do other things. For instance, here I approached my role from an atmospheric standpoint, and I tried to tie things together and do little things that I wouldn't normally do on a Rush record. For "Beyond Borders" everybody basically had their parts worked out and knew what they were going to do, but because it was in the studio arena, it had a whole different perspective to it. The work was a little more precise, so things took longer. Since we were working on vinyl, we wanted to make sure it was done right. It was fun and very satisfying.

Liona Boyd: The fascination for me was to work with these particular players. I had listened to all of them before, but I wasn't intimately familiar with their styles. Right now I'm expanding my artistic scope a little more, so I was eager to play something different and more experimental. It was a change from being a strictly classical guitarist.

Ed Bickert: One of the things that Rik and I talked about a bit was how a project such as this is going to interest some listeners in other styles of guitar playing that they might not get exposed to otherwise. People who are familiar with one or the other of us will be able to hear the rest of the stuff and say, "Hey, that's not so bad." In that respect it serves a good function.

Rik, did you feel self-conscious about presenting your ideas to such established artists?

Rik: In the initial stages I didn't want to go too far, because I was dealing with respected players, which made it difficult to say, "Here it is; play it." I tried to present my ideas as being more of an outline. As it turned out, everyone is so gifted that they gave my thoughts a whole new perspective. That certainly happened when Alex began working. The parts I initially had on the tape before Ed came in were Mickey Mouse compared to what he did. He made six takes for his solo, but everyone of them would have knocked you on your can.

Alex: Ed and Liona also contribute a lot of transition points and segues, in addition to the places where they were featured. The little bits that come in and out add a lot to the flow and work nicely, especially for something that was basically done in just a couple of days.

Liona, how did Rik 's score differ from other things you've done?

Liona: It was written by a guitarist. When you try to play a piece by a non-guitarist who doesn't quite understand the possibilities or the limitations of the instrument, it can be frustrating.

Was there anything that you learned or did differently that you might not have done in your normal musical environment?

Ed: Just ask me what kind of strings I use [laughs]. Most of the times when I record, the person in charge usually tries to move the session right along, as if you were playing in a club. So in that respect, being able to make six or so takes was a luxury. I also had the opportunity to listen back to see if what I did was okay. You could say it's a first, in that I laid down some chords and overdubbed a solo over them. Things were also different, in that I don't expose myself much to other areas of music-I'm kind of a stick-in-the mud that way. Although I just came in and did what I always do, it's surprising to hear how it all came together in the end. Doing this proved that all of these things can work together.

Alex: After spending the day here in February when I recorded my guitar solo, I was reminded that I really love playing the guitar. When you do it all of the time, sometimes you forget that. When you perform in a concert hall, it becomes ajob. Although you might love your job, you lose something. Playing the guitar is a wonderful feeling; it's a great expression.

Liona: I get very moody if I haven't been able to play guitar for a while; it's almost like having an addiction and going through withdrawal symptoms. I get grouchy. But after I sit down for five or ten minutes, I suddenly start to feel good. One ofthe things I did differently was use Lenny Breau's harmonic technique, which Chet Atkins explained to me years ago . There aren't any classical pieces that use it, so I had to refresh my memory to learn it again. Now I'm incorporating it into quite a few of my compositions. It was an education seeing how the different playing styles worked together. The whole wasn't apparent until the end, because Ed and I did our bits more separately at the beginning, and then Rik and Alex came in. [Ed. Note: Lenny Breau's octave harmonic techniques were featured in his columns for May through Oct.'81.]

Ed: Sometimes playing the guitar makes me feel good, and sometimes it makes me feel as if I should be in some other line of work [laughs].

Rik: Speaking of doing things differently, when Liona played her part, only a click track was on the tape, so she was really in the dark. I had planned things that way. Since she is the most schooled player, I knew that she could read a part and play to a metronome. I knew that she'd have the best timing, so she laid down the skeleton, and Ed provided the next layer. I had recorded a bass line for him to relate his playing to. Liona: I hate working with click tracks, but you have to when you record with other people.

Alex: Rush would never work without a click track. As soon as you get into drum machines and syncing up sequencers, it 's essential that you use one.

Alex, you mentioned working with textures for this project, but you've always done that with Rush.

Alex: Well, now we rely fairly heavily on keyboards and sequencing. You can sync up five or six different sequences on different keyboards and have a fantastic atmosphere and sound texture. My part in Rush ends up being more of a stricter guitar part, instead of an experimental thing. That's fine and it satisfies me in that context. When I got involved with this project, everything was just about finished, which enabled me to sit back and put my feet up and play whatever I wanted.

Rik: Alex was kind of like the keyboard player for our band. He came in afterwards and did all the keyboard-like overdubs.

Jazz, classical, and rock approaches to rhythm are very different. Was that a problem?

Rik: I knew that one of the trickiest parts would involve making everyone's sense of rhythm work together. For instance, since Liona comes from a classical background, she thinks in the middle of the beat, whereas Ed is very laid back and ready to start swinging at any moment. With Alex and I the beat is all over the place. Sometimes we get excited and we're way ahead of it, and then we start to bend notes and get way behind it. So you obviously run a risk when you try to make all of that work together.

Liona: Actually, classical guitarists don't even think of the beat that readily. It's been an education for me to do something that's so rhythmic, because in most classical music, the beat is not clear. Every conductor I've worked with says that guitarists are so used to playing on their own that they don't really pay attention to rhythm.

Alex: In contexts such as this, rhythm is a function more of feel. You immediately start tapping your foot, because the music has a certain flow to it. One of the great things is that we didn't use a drummer or a rhythm section. It's strictly guitarists and nothing else, so we had the freedom to do whatever we wanted.

When you first heard of the project, were you apprehensive about it?

Alex: I had a lot of reservations at first. I thought, "These players are very good; I'm gonna feel a little weird playing with them. " But after talking to Rik, I felt better. I wasn't sure what the piece would sound like, but I thought that it was a great idea. If we had recorded it together off of the floor, the result would have been a lot different; we wouldn't have had the flow, and the piece wouldn't have been as interesting. When Rik first sent me his demo, I wondered, "What have I gotten myself into?" But once we got together, we joked around and plowed through it. It was fun, and it didn't hurt.

Liona: I was apprehensive. I hadn't heard the piece, and I wondered how we could play together. At first I thought that the four of us were going to play together. But after talking to Rik I realized that it was going to be built up and that I was going to have a score and not just be expected to improvise along with Ed. Once I had heard things, I realized that I' had some very pretty parts, which made me excited. I have to give Rik all of the writing credit, because I didn't contribute to any of it.

Rik: You always run a risk with something like this. In the initial stages I tried to be as flexible as possible, so I had to feel everyone out to see how they could fit in. In Liona's case, I figured out that the best way to go was to record a rough outline of a part, which I sent her so that her guitarist and arranger Richard Fortin could do a transcription.

Each of you is a world-class artist who also happens to be Canadian. When you got involved with this project, did you see it as an opportunity to make a nationalistic statement?

Rik: I'm not making any claims; it just so happens that Guitar Player is based in America, and we are from a semi-foreign country. We live in the same area of Canada, so maybe it would be better to call it Toronto Guitar Summit, although Toronto is a hotbed of talent.

Alex: When you're from a smaller country, you don't really think about nationalism. It doesn't occur to me that I'm a Canadian musician. I'm a musician, period. There are many good Canadian musicians, and probably some bad ones, too. We've become more visible internationally, and the industry has grown a lot here. Record companies are more willing to take chances on Canadian artists now; 10 or 15 years ago you had to go south ofthe border to accomplish anything on a large scale.

Liona: We have the advantage of being near the U.S. market and being supported by Canadian audiences, which are very good.

Rik: Canada has a fairly strong multicultural mosaic, and we are in the shadow of a huge cultural sister. We are influenced by Britain and France, but right next door we have Chicago, where the blues came from. Ed: Everybody around here says we are not getting the opportunities to play, there aren't enough clubs, and people don't turn out for festivals and concerts the way they should, yet maybe the jazz scene here is much more active than that of other places. Jazz musicians complain, but maybe it's a pretty good scene, comparatively speaking.

Is there a "best guitarist" among you?

Rik: You really want me to try to answer that? Okay, it's me [laughs). Seriously, it reminds me of how much I dislike the whole "poll winner,""axe slinger" mentality that pollutes the guitar community. Kids hang out and argue about who's better between Yngwie Malmsteen, Eddie Van Halen, and Steve Vai. Music isn't a race; it's not a competition. Being a Guitar Player columnist and doing clinics gives me the opportunity to influence younger players to not think in terms of who is better. We are four guitarists who are great at certain things, if I can be so egotistical as to place myself in their company. Ed can't do what Liona does, Liona can't do what I do, and I can't do what Alex does. But we can lend things that enhance each other's musicality and playing, which is the most important thing. So the whole thing of who's best is nonsense.

Liona: We have unique things to offer in the guitar world. I would be a lousy electric guitarist or jazz guitarist, and Ed might be a lousy classical guitarist. We do what we feel inside. You give yourself to the music that suits you. I couldn't feel jazz the same way that Ed does. A while ago I gave up contemporary classical music because I felt it was an intellectual exercise. I performed the pieces, but my heart wasn't in it, so I stopped. I got a lot of criticism for that. It's good music and I enjoy hearing others play it, but it isn't me.

Alex: There is no competition; everybody is different. Music comes from the ear and from the heart. It can affect you in so many different ways that it's unfair to place one above the other.

Ed: We all make music the way we can. I like Paul Desmond's remark about how he won quite a few awards for being the slowest saxophone player in the world, and that he earned a special honor for playing extra softly. There certainly wasn't any competition in a project like this; each of us made our particular contributions, and that was that. I suppose that when I play with other musicians, my main objective is to complement the other musicians' stuff.

Rik: To finally answer the question, in one respect Ed is the best guitarist, in that he works on an instinctive level, being comfortable with what he knows. He's always able to find the right place for his playing in whatever music he's doing. The rest of us are younger and still searching in a lot of ways. Lionaisjust starting to be a writer, and Alex and I have been insulated in the rock band environment for years and years, so it's only at this stage in our careers that we are starting to step out and learn more about other music ensembles and structures. So in that sense, Ed's the best.

If Rush is a bit limiting, how do you expand yourself musically?

Alex: The limitations inside Rush are not that great, but they are there. There are certain things that you wouldn't try doing, due to the particular combination of musicians working together and the direction. But apart from that, there is a world of sound and ideas that I can look into, although I'd love to work with some other people, too. I have a particular style, and I'd like to explore how I can implement it in other music and songwriting. I've done a couple of things outside of Rush, which has been extremely satisfying. I like many different forms of music, and I like to experiment with them. Having a studio at home is another good way to have the lUXUry of getting into other music in a fairly big way, but without having to spend a lot of money and time. I don't feel that I have to market music done that way; I'm lucky enough to have the freedom to make that choice.

Do you have a secret desire to play styles other than your respective specialties?

Ed: I've always been an admirer of classical guitar, and I've dabbled with it in a very small way. I've tried to learn a few of the pieces in the standard repertoire, including some of Villa-Lobos preludes, but I've never had the technique to be able to cover playing classical, and I would never do it in public. I realize that there are a lot of good players around, but most of my listening experience goes back to older times and records by Segovia, John Williams, and Julian Bream. I would like to be able to play some more contemporary music- not necessarily rock, but jazz that's a little more up-to-date, which is a different kind of thing compared to what I generally fall into. But I've been too lazy to develop that type of stuff. I'm not anxious to get into fusion playing, but some of it appeals to me. I'd like to be able to do it to some degree. Allan Holdsworth and John McLaughlin are up-to-date musicians who are pretty interesting and have unbelievable facility. Ralph Towner also does a lot of nice things.

Rik: I'd like to answer the question in terms of technique. The next aspect of my playing that I want to work on is my right hand. Hearing Michael Hedges recently reinforced that point. I'd also like to develop some ofthe two-handed playing that Steve Vai, Eddie Van Halen, Steve Lynch, and Stanley Jordan do. In my own music I want to get into fusing styles, rather than learning another separate one. Mixing different forms is getting more acceptable to the music world. Right now I feel as if I'm in transition, in terms of direction, but nothing definite has developed. One thing I've observed about my own playing is that I tend to think traditionally, using standard tuning and usual chord voicings. I'd like to get away from the academic thing.

Liona: I would like to be able to improvise more freely. It would be nice to have the knowledge of someone like Chet Atkins. He knows a lot about jazz chords; I don't, because I haven't been trained in that way. I concentrated on the classical approach all my life. I'm learning a bit about jazz now that I'm branching out and doing different styles of music, but I don't imagine I'll ever be ajazz player. It's not something I've ever wanted to do, although it can add an extra dimension to your playing. I've never been attracted to jazz music in the way that I am to classical. Classical speaks to a different part of me. Without sounding like Christopher Parkening, who is very religious, it has a spiritual quality. Chet is certainly not a pure jazz player, but I appreciate his versatility. It's a shame that when you study classical music, you are not given a wider education that includes other styles, which would be useful for young players. If I were teaching guitar right now, I would train players to be more versatile and have more basic knowledge of jazz progressions and structure. Practically speaking, most players, other than the very select few who are able to have classical concert careers, could benefit from being familiar with other styles.

Alex: About 15 years ago I studied classical guitar for about 12 months, and I really regret not keeping it up. I remember the pieces that I originally learned, and if I practice for a while, I can get my fingers back into relative shape. Some of the things I know are fairly standard for grade-six level and include transcriptions of six lute pieces, "Bouree In E Minor" by J.S. Bach, a couple of short works by Fernando Sor, and a few flamenco pieces. I also know a sonata by Scarlatti, which I heard on an album by Segovia. I always liked that piece, so I got the music and took the time to learn and practice it. I still don't play it very well, but I try. It's never too late to develop a style like that. Solo guitar is very satisifying; being able to play the guitar alone is one of the best things about being a musician. When you play by yourself, the guitar sounds so beautiful because of the combination of harmonies and melodies that are possible. One of my classical instruments is a 1971 Ramirez that I bought in a Denver pawnshop in 1975. Liona once asked me what year it was, and she said that a guitar is like a bottle of wine; particular vintages of Ramirez guitars are better than others. The '71 is beautiful-sounding. The bass is quite deep, but the top end is very bright. It has a thick sound board, and it's not the easiest guitar in the world to play.

Not all guitarists are as well-versed in the technical aspects of recording as are Alex and Rik. What are the advantages to knowing your way around the studio?

Liona: It's certainly helpful, and it may be something that I'll spend more time with in the future. But you have to make choices in life, and I've decided that a terrific engineer can be very beneficial. I'm fussy about the kind of sound I want and what mikes are used and how they are positioned. I've always been involved in the sound that I've gotten, especially on my solo records, but I don't pretend to know all of the technical details about how things are mixed . I've watched mixing, editing, and every stage of a record being made. Obviously, Rile and Alex have been working a lot more with multitrack recording; most of the time I've worked with solo guitar, although I was present while my albums Persona and Romantic Guitar were being mixed. Maybe it's just that men are more interested in the technical side of things. I know the sounds I want, but I'd rather let the engineer handle everything. I'm capable of doing it, but it's not my real love. I've always been involved, as far as the editing of all my albums goes, so when I hear a guitarist say that he lets the company edit his records, I think it's just out of laziness. Who better than the artist knows what they had in mind for a certain interpretation?

Ed: When I record, I usually do my own thing in my own way with my own equipment and my own style. The people in the studio understand that off the top, so I haven't had to adapt to all of the complicated equipment. If my sound is in question during playback, I just say, "I'd like a little more of this or a little less of that." Usually there's no problem, and they make the adjustment. So far I've managed to get by, but I admire people who are familiar with the process.

Rik: Everything helps. For instance, some artists need a good producer, especially at critical junctures in their careers. One of the ways to educate yourself is to have a home studio, which will help you understand how things such as EQ, echo, and a mixing board work. Some artists get set in their ways, so it becomes hard to change. It's unbelievable to hear that players such as Ed record so quickly; I'm used to making records where it takes two days just to get drum sounds. Depending on the kind of music, the attitudes are completely different. Way back when, an artist was an artist and an engineer was an engineer, and never the twain shall meet. Nowadays, engineers are producers are writers are instrumentalists are vocalists. Steve Lukather and Larry Carlton are good examples of instrumentalists who know what they're doing in the studio. I've been listening to Larry Carlton a lot lately, and I really like the action that cat's got-he does it all.

With such busy careers, how do youfind time to practice and advance musically?

Ed: At this time in my life, I'm not disciplined enough to practice and do a lot of listening and research. I certainly have guilt feelings about that. You could say that I do what I do, and that's about it, but that wouldn't be 100% true. From time to time I work out musical ideas that are different, or I get some pieces of music that are more modem than my knowledge. I also try to stretch my hearing a bit beyond what it's used to. I'm not sold on the idea of staying at the level I've reached, so I'm still open to learning some new things about harmony. There's an awful lot of technique that I could improve on, to help me play what I already know. I could also stand to learn some stuff that's more energetic- I guess that "fast" is the right word, although sometimes it's more a matter of making things sound effortless, rather than fast.

Rik: When you're young you tend to go through a very intense period of working on your chops. As you get into your twenties, you start developing a career and you have to spend time figuring out your writing, engineering, record production, and those kinds of things. But after you get your career going, there's time to go back and woodshed and recapture a bit of the artistic aesthetic that you had in the early stages. Andy Summers is a good example of someone who found success and then went off to do more creative things, such as film scores and albums with Robert Fripp that are pretty esoteric. So at this point in my career it's a matter of parceling my time so that I can develop as a player and break new ground.

Liona: I spend a lot of time listening to other music- not just guitar music necessarily. It takes time to advance musically. Occasionally I go to see Eli Kassner, who runs the Toronto Guitar Academy. Performing helps my pieces the most. I can play something for months on end by myself, but it undergoes a transformation once I start playing it in public. I always hate the first public performance of a piece, but other expressions come into it after a while. Segovia once said that he likes to play a piece in concert for five years before he records it. I divide my time according to the different things I need to work on. As you learn new material, you have to keep up your old repertoire. Sometimes I'm in the mood for writing instead of practicing, while at other times I've got no inspiration at all and I'm only in the mood for watching TV and doing scales. When I'm on tour, I usually practice only 20 minutes a day, but if I'm rehearsing for a major concert prior to touring, I do about an hour of technical stuff.

Alex: It's funny because one of the reasons I stopped taking classical guitar lessons was because the drinking age in the province of Ontario was lowered from 21 to 18, which caused the number of clubs and bars for Rush to play to just explode. Up until then I had time to work on my music; I took my guitar everywhere and played for friends as much as I could. But I had to let things slip when my interest focused on what the band was doing. I still took my nylon-string on the road, but it wasn't quite the same. Now I have to squeeze in practice time whenever I can. For instance, in the studio I like to play constantly between takes. Once when Steve Morse opened for us, I noticed that he played all of the time. Even while carrying on conversations, his fingers went up and down the fingerboard. Once you start doing that, your fingers become very limber after a couple of months, and you feel very comfortable about your ability as a player after a while. At home, I do that same thing. When I practice, I play melodic ideas, scales, or chordal things. One of my favorite exercises involves playing a four-finger pull-off starting on the high E at the 12th fret with the 4th finger; you just evenly pull off each note in the position, and then repeat the pattern a fret lower, and so on. Stylistically, I'm not looking to learn something innovative, different, or new; I'm quite happy with my ability. I'd like to be a little better and more confident, but I don't want to learn two-handed hammer-ons and that kind of stuff, because it doesn't interest me.

Rik: I'm curious to hear if Alex thinks it was easier for a band to be more adventurous in the mid '70s .

Alex: There seems to be more experimenting now than in the mid '70s-in rock music, at least-but the results don't seem to be as honest or as complete in a musical sense. The rock guitar vocabulary really hasn't expanded that much-it's probably gotten a little quicker, but most of the players are just saying the same things faster and flashier. I guess it's like that with every phase of rock guitar. You get a number of players who seem to establish a direction in playing, and then everybody follows, although now there are different forms of rock and different styles of playing. In some types, the guitar is more of a rhythm instrument, rather than playing a traditional lead role. Still, a lot of bands sound very much the same. Most heavy metal stuff doesn't have much variety, possibly because it's not inherent in the abilities of the players or in 'their creativity. In some music, textures have taken over quite a bit, which includes the use of artificial instruments such as synthesizers and drum machines that substitute for the rhythm section. There is a big difference between a real drummer and a drum machine; you can feel it in the regularity of the playing. All of that stuff affects the synergy of the musicians.

How would you answer purists who object to you going beyond your respective forms of music?

Liona: A lot of classical purists have given up on me anyway, because of the various things that I've been doing over the past couple of years, including associations with Gordon Lightfoot and Chet and putting more popular pieces in my classical concerts that aren't in the Julian Bream/ Segovia tradition. But what the narrow-minded classical public feels is not really of concern to me. Recently I've made quite a career change, and I'm very happy with my new way of expression and working with other instrumentalists. I'm writing a lot of the music myself now. I've always felt that I'm a creative person, yet I never thought that I could write. Years ago Gordon Lightfoot recommended that I write my own things, but I just laughed and said, "Segovia, Williams, and Bream don't do that. " A lot of what I'm writing falls somewhere in between rock and classical, and it has a lot of different influences, including South American and Caribbean rhythms. This is the direction I want my career to go in, because I enjoy working with a band. I'm not going to give up solo concerts, though. There is something very magical about how the classical guitar can create an entire piece of music, but a whole new world has opened up for me that involves playing with other musicians and using synthesizers and drum machines. I enjoy concerts where I'm playing with a band; I'm more relaxed. I can get much more involved with the music, compared to when I perform with a symphony orchestra, because classical guitarists don't get to play with them that often. Most artists are always reaching out to larger audiences. It's the worst feeling in the world when you go into a town and you hear that only a third of the tickets have been sold and you're losing money, but it's great when the hall is packed. When I started out with classical guitar, I thought that I would strictly play for classical audiences, but over the years I realized how broad the audience is and how it does go beyond borders. It's really unique.

Alex: Rush has been lucky, in that we've always satisfied ourselves before our audience. We have a large following that appreciates that we're sincere and honest with our music. Our attitude has always been, "If you don't like this record, too bad; maybe you'll like the next one. " We're proud of what we've done, although we might be dissatisfied with it later.

Ed: It's unfortunate that people aren't more accepting of different kinds of music, and more easily exposed to it, but it's been like that for so long that I don't even think about it anymore. That's just the way it is.

Rik: Somebody has to take the bull by the horns to try to overcome the prejudice that exists in the musical community. It's a courageous move when Liona makes an album like Persona, for instance, It's something that she didn't have to do; she could have just gone on making a nice living doing what she was doing. When you do something different, you run a risk. At the same time, an artist has a responsibility to do that, because in the end that's the way you overcome people's narrow notions. Most prejudice is based upon ignorance; people don't know any better. When you make a record with four different people on it, someone who likes Ed Bickert, for example, will get exposed to the other guitarists. I think that some of the prejudice from Liona's area, say, is harder to overcome than with what Alex and I do. We make our livings in areas where there are no rules. Rush fans and Triumph fans are used to classical guitar parts here and there.

Liona: Most musicians appreciate a wide variety of music; it's the audience and the critics that sometimes have the problems.

Rik: Boundaries and borders should have nothing to do with music. I like what John McLaughlin's album Music Spoken Here [Warner Bros., 1-23723] signified: no rules, no boundaries, no preconceived notions. Doing what your heart and soul tell you is what music is supposed to be all about.

Special Extended-Play Soundpage

Canadian Guitar Summit

"Beyond Borders"

By Rik Emmett

As told to Jim Ferguson

As told to Jim Ferguson

The "beyond borders" project grew out of an idea that I had to do a fusion piece. Conceptually, I wanted something that would break down boundaries between different styles. One of my pet peeves is the prejudice, ignorance, and phony walls surrounding various aspects of music, so this seemed to be a chance to do something about that. At the same time I wanted to get great players to execute my ideas, which went beyond my own limited techniques. From the beginning I thought that using local talent would make it fairly easy to get together and overcome the logistics and political kinds of problems that can develop when you deal with people from varied careers. [See Soundpage, page 82.]

Since this was a non-commercial venture, it was relatively easy to appeal to Liona, Ed, and Alex. Commercially, the project doesn't have a lot of potential; a six-minute piece with four guitarists from different walks of life isn't going to go Top 10. Everyone got involved out of their love of the guitar and music; it was as simple as that. The experimental and educational aspect of "Beyond Borders" really piqued the players' interest.

Once I heard that Guitar Player was interested in having the project be a Sound page, I wrote and phoned Liona, Alex, and Ed, and then sent them a basement demo tape that outlined my vision of the piece. Next came a meeting at Liona's house with Ed and Richard Fortin, her arranger and transcriber who plays in her band. We kicked around some ideas and spent the next day in the studio with Ed and Richard. Liona's part was completely solidified, and Ed got an idea of what he would be doing and signed off on the tempos for each of his sections so I could make click tracks. After that, I put down a basic acoustic guitar skeleton to help guide everyone through the various sections.

In January, Liona came into the studio and spent the better part of the day recording her parts. Next, Ed came in and spent a few hours doing his stuff. It was funny because Ed had hardly played a note during the previous meetings, but I had a feeling that when it came time to record, he would be completely prepared. That's exactly what happened. Every take he did was fme and perfect, so doing more than one was a matter of getting something that was interesting.

Meanwhile, Alex and I had been trading tapes through the mail. We discussed the kind of role he would be playing and basically decided that he would provide atmosphere, but we wouldn't use any synths- just direct kind of guitar sounds and outboard studio gear. It surprised me how cooperative everybody was and how each of the participants had a professional graciousness. When the need to compromise came up, there was never any problem. For example, when Liona did her tremolo part, as a producer I requested that she go for a very emotional performance, because the tempo was very open to interpretation and not very metronomic. When Alex listened to it, he said that he would have gone with a very straight reading-exactly the opposite of my idea. So when Alex and I mixed that part, we decided to give it a little back reverb but to make it fairly up-front and personal sounding.

When Liona listened to the mix, she wished that it had had more reverb to smooth out the tremolo a bit, but she was perfectly willing to live with it. Later Alex I and talked about how everyone was able to put their egos aside and be more concerned with the music rather than showing off their chops. This might even be a Canadian trait, although I've been in other collaborative situations where it wasn't necessarily that way, such as jamming with other guitarists. I was very happy to have Ed Bickert get involved with the project, because he deserves more recognition. He is extremely laid-back and humble, so I saw the project as a way to expose him to a much larger audience. In many ways this addresses the issue of how the artistic side of music opposes the commercial side. There's a fair amount of injustice that exists when Alex and I can be popular and financially rewarded for what we do, while Ed's music remains largely unknown to the young record-buying public. I find it ironic that Ed is very quiet, yet his music is so articulate and has such a depth of expression.

As the composer of "Beyond Borders," it was great to collaborate, because the other participants provided reinforcement and assurance that I needed. When you work alone, a lot of self-doubts can arise; but with colleagues, you find out that a particular idea isn't lunar and has some validity. Also, others recognize your strengths. For instance, at the end of the piece, I had a place for some semi-fancy lead playing that dances around and is fairly quick. I wanted Alex to play that part, but he said, "Oh no, I don't know whether I can pull it off as well as you can, so I think you should do it." It makes you feel good when someone you respect says something like that.

Liona has a very good right hand, so I decided to write to that. Her attitude is pretty amazing. She has a competitive and ambitious spirit, but at the same time she's a very gracious and classy lady. It's interesting to find that all in one package. I wrote about 80% of her part, while Richard contributed 13% and she added 5%. Usually when a piece is performed, the composer is responsible for about 90%, and the remaining 10% results through the artist's interpretation. For example, Liona added a lot of interpretive color to the piece by artistically moving her hand towards the bridge for a brighter sound. I also have to give her credit for naming the piece "Beyond Borders."

One of the things I learned about Alex was the way he conceptually approaches a recording; he's able to look at a piece of music from the outside in, rather than from the inside out, which is my way of doing things. He thinks a lot in terms of flavors, colors, textures, and atmospheres. He refers to all of the little details that can be added to a performance to make a chill go up your spine as the "GB factor," which stands for goose bumps. In fact a couple of times during the mix he showed me how he was actually getting goose bumps on his arms from listening to the playback. When it comes to studio equipment, he has a great understanding of the board and outboard gear, such as reverbs, delays, and EQs. This was the first chance I'd had to get to know him, and he was really great to work with. Most people think of Alex and being part of a very serious progressive band, but he's one of the funniest guys in the world.

A fairly large array of equipment was used on the recording. Ed calls his sound "Scarborough dark" -Scarborough is in the greater Toronto area-which describes its warm quality. He used a Roland Cube amp, with the EQ and master volume wide open with the channel set at about 5. He plays a mid-'60s Fender Telecaster with a humbucking pickup in the neck position; he never uses the bridge pickup. Ed keeps the tone control adjusted close to full bass, and the volume control is close to wide open for soloing; he backs it off a bit for com ping. He also keeps the Allen wrench for the bridge taped to the body so he won't lose it, which is pretty funny.

Liona's guitar was built by Kato, the guitar maker for Yamaha. She also has some Ramirezes and a soprano guitar that was built by Serge DeJong, a Toronto-based Iuthier. Alex used an Aurora model made by the Signature Guitar Co. It's equipped with an IVL Pitchrider synth pickup. He used a Gallien-Krueger 250 ML basically as a preamp to drive a Marshall twin-l 2 combo and a Dean Markley CD 212. For lead work I used a Yamaha RGX 1220, and the jazzy stuff was played with a Yamaha AE 2000 fullbody archtop. The acoustics included a Yamaha L-45 6-string and an old Ovation l2-string. I also used a variety of novelty guitars, including a Coral Electric Sitar loaned to me by Domenic Troiano, and an old metal-bodied National Dobro from the '30s that I borrowed from Paul James. My amps included a Fender Princeton Pro Series and an old Marshall 50-watt head and a Marshall 4 x 12 bottom.

Balancing the electrics with the acoustic was the biggest challenge involved with the mix, especially in the busier sections. Three of us were at the board: Alex, myself, and Ed Stone, the engineer. Ed made suggestions and basically ran the board. Alex and I had our own little moves to do. The 24 tracks were completely filled up, and some of them were double assigned, so Ed drew up a map, which helped us keep track of the various elements. Alex likes to do things such as set one echo repeat on quarter-notes or halfnotes and another repeat in a triplets feel, so you get the two beating around in a texture that's rhythmically correct. In general, the mix was fairly straightforward.

When I first started to arrange "Beyond Borders," I adopted the basic premise that it was to be a guitar quartet that could be played live onstage. Even though we might never perform it under those conditions, that idea helped me limit the writing. Now that it's finally recorded, it still could be done live, although we would have to cheat a bit and probably use a guitar synth hooked to a sampler for parts such as the triad section at the end. Also, Ed might have to be persuaded to playa little acoustic guitar, and Alex and I would have to scramble like crazy. But it could be done. The other concept behind the arrangement was to have no synths, drums, or bass guitar, as I mentioned earlier.

"Beyond Borders" is basically 120 bars long, and it begins with an adagio section with a tempo of 72 beats per minute. I do the lead guitar off of the top, and Alex plays the atmospheric stuff in the background, which includes low weird things and floating sound effects. Ed comes in with a little melody that lasts from bar 4 into measure 5, and then Liona's little melody enters at bar 6. The lead that comes in at measure 8 is Alex. In measure 15 Liona plays a little classical lick that Richard Fortin wrote. At bar 17 I play a long feedback melody that continues to measure 26.

Liona begins her classical tremolo solo at measure 22; in the background you'll notice the feedback guitar part. Liona's and Ed's parts cross at bar 28, as Ed takes over with a rubato chord-melody solo. At measure 33 he kicks into an allegro tempo of 140 beats per minute. That's where I back him up with a simulated bass guitar part that I play on my Yamaha arch-top. For the warm bass sound I rolled the treble back and played with the fleshy part of my thumb. Ed does a cadenza at measure 64, and Alex plays an atmospheric technique where he holds a chord and brushes the strings quickly with the fleshy pads of his right-hand fingers; Lenny Breau was the first person I saw use that.

Bar 65 has an adagio tempo of70 beats per minute. I play the lead guitar, and Alex adds the arpeggiated electric guitar part behind it. That continues to bar 76, where Liona plays her Lenny Breau octave harmonic lick. That's also where I begin using the Coral Electric Sitar, with echo repeats on it. Bar 77 is semi-country acoustic fingerpicking with an andante tempo of 90 beats per minute. I play the acoustic steel-string, and Liona plays nylon-string in unison, all the way to bar 102; sometimes I break into harmony, but it's a unison part essentially. During that same section I also play the Dobro part and all of the electric fills that have a Pat Metheny-esque sound. Alex did the violin sounding swells in the background with a volume pedal.

Where measure 101 crosses over to 102, I did a little lap steel thing with a volume pedal and echo that goes up from a fifth to an octave; it's kind of a Steve Howe cop. Measure 102 is the beginning of the end. Liona plays the little classical part, and then I break into the harmonies above it. During this section I did all of the wire choirs, which are triads with some of the voices doubled, and I also played the 6/ 8 melody lead guitar fills on the tag right near the end.

I want to give credit to Louie Muccilli, an old friend of mine, who is responsible for the melody that occurs at the last ending part of the piece. Louie and I played in basement bands together. He has a straight job now, but he's still plays great. Recently we got together to do some writing. We began listening to an old tape that we had done, and all of a sudden I recognized a melody he had written that I unconsciously used in "Beyond Borders," so I immediately apologized for stealing his lick.

One of the greatest difficulties in doing a fusion project such as this is successfully marrying the various elements. For example, Liona's classical solo has a bit of a rock feel laying in behind it, but Ed's part is pure jazz with little integration going on. So getting a more complete blend of the styles is something to still shoot for. Another difficult thing was trying to satisfy the standards of four international recording artists on a limited budget. It's one thing if you're Roy Buchanan and you go into the studio and record a jam for a couple of hours, or you're Steve Vai working in your basement studio, but it was very difficult to be concise and make people live with things on a project that was this experimental.

In the final analysis, "Beyond Borders" confirmed my feelings about guitar's potential. Traditionally, it's a very accessible and personal instrument, and it's perfect for realizing all kinds of fusion-not just jazz-rock. It's very flexible and can accommodate practically anything you can imagine. If you can dream of something, it can be done.