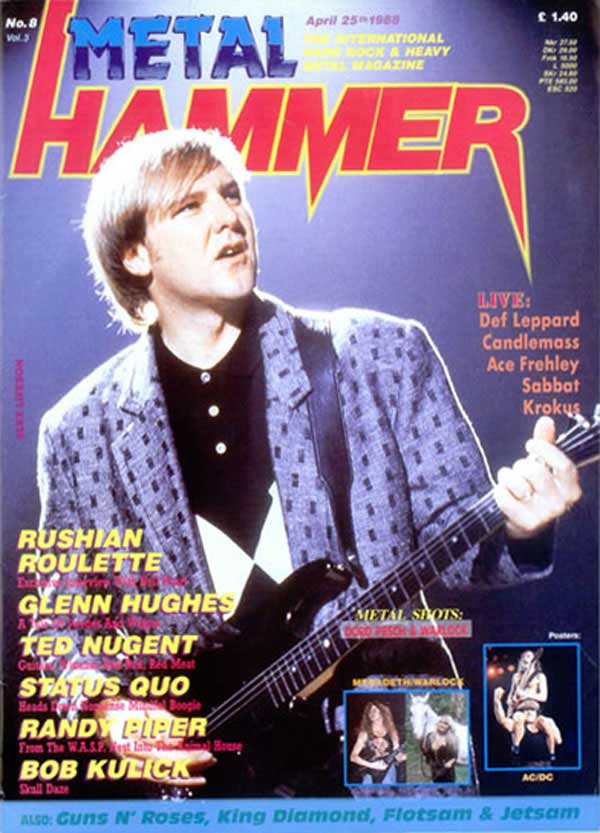

All Fired Up

An Interview with Neil Peart

By Malcolm Dome, Metal Hammer, April 25, 1988, transcribed by Andrew Brooks

How do you think people perceive you as a person and as a musician?

I regard that question as irrelevant to my position as a musician. Maybe you should ask me if I care?

OK. How do you think people look upon Rush as a band?

It's so difficult to generalize about something like that. Even if you accept that there are about a million people who would be considered fans of the band, they probably have a variety of reasons for liking us and it's beyond my presumption to question their positive attitude towards us. As for the rest of the world and the reasons they don't like us... again it's an impossibility to state what these are.

You are a band who've changed considerably over the years, yet have retained the faith of most of your original audience. Does that surprise you?

The fact that we've developed and changed so much yet held onto our audience isn't that remarkable if you consider that what we've done has been an honest response to situations around us. We started out as fans of the late Sixties style of music, which was dominated by the likes of Jimmy Hendrix and Cream -- musicians. I was personally inspired by the Who, they were the first band to make me wanna play drums and write songs. At that time it was really the music that mattered and the idea of formulae for making music, record companies running things, or radio stations 'formatting' was totally alien. Such things were never considered back then. Sure, you realized that if you were in a band that didn't play Top 40 music then you might not get so many gigs... but then you were going to school at that point anyway! You just played the music you liked and let it go at that.

That's where our musical values were forged, but because we stayed interested in music and our music stayed open as a band we were able to respond in the late Seventies as fans when the idea of minimalism came to the fore. Thus, when the best emerged from the dross, the likes of Talking Heads and the Police, we were able to take its influence into our format. And the same occurred again, when the second generation of this movement such as U2 and Simple Minds came along -- as genuine listeners we had to be influenced by them. In many ways we are a big musical sponge, reacting to the times in a genuinely interested fashion. We are not bandwagon jumpers like so many others. Even in the Sixties there were loads of acts who would happily jump from bandwagon to bandwagon; the Beatles certainly did this from time to time. They'd be at a loss, and then look around at what was happening; I reckon they'd say something like, "Hey, that sound's good, let's get into that!"

Where do your lyrical influences emanate from?

My influences are very nebulous. They come from growing up, it's kinda like my musical stylistic evolution. I started out, of course, with a lot of fantasy and because I was a post-adolescent this reflected my interest and sensibilities at the time. Everything was dressed up in a lot of ornate imagery. From there I moved onto allegory and symbolism, dressing up big themes in symbolic characters, none of which I have any use for these days. I believe that I've grown out of such a style both as a person and a writer.

I grew from this into modern fiction, dealing more with reality and using a clear, concise language. Not a lot of this has anything to do with verse, it's more prose form, especially North American writers. These days I read a lot less fiction. I'm much more into non-fiction, particularly history and sociology, geography and the world around me. If I had to define that part of fiction which has had the most profound influence on me, though, it would definitely be the 1920's and 1930's American writers, people such as William Faulkener, Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald. Their whole ethic was dealing with reality and the world in which they found themselves rather than gothic romances, sci-fi or fantasy. At the same time, they had a very romantic sensibility and tackled the world with a sense of love. Even when there was cynicism involved, the darkness was still presented in a stylistically beautiful manner. It became a sort of romantic realism to me.

Where did you draw your lyrical themes for the latest Rush LP ('Hold Your Fire') from?

Well, firstly let me say that I care about anything I go to the trouble of writing about. I get a lot of response about our most recent album from people who regard the lyrics as highly personal, which is a compliment but totally untrue in many respects. I deal on the record with a lot of emotions and intimate things and a lot of relationship ideas, but they're all taken from other people. If I chose to write them from the perspective of the 'first person singular' then it was because that was the most effective way of transmitting my thoughts.

OK, in general terms where do you find the inspiration for songs?

My subject matter is drawn from other people, although it's nice to find a personal parallel if something upsets me. Anger is always a big motivation, and outrage gets me all fired up. But one thing I particularly hate is confessional lyrics, the one where people reach down inside their tormented souls and tell me how much they hurt -- that's really selfish and petty! If you have all that pain, by all means express it but be a little self absorbed about it and look around you at other people, because everyone has pain and frustration and you can find parallels if you look for them. For example, the song 'Distant Early Warning' (from the 'Grace Under Pressure' LP) contains the line 'The world weighs on my shoulders,' which is an expression of worldly compassion that any sensitive person feels occasionally. You feel so rotten, because the world is such a mess, so many people are starving and unhappy. It's an extreme that represents a feeling most people have from time to time. Yet I certainly wasn't going to put it in terms like 'Oh, I'm so depressed.' I wanted to get across the point of world-weariness and sadness rather than self-pity.

This theme is a recurring one of mine, and even on 'Hold...' there's 'Turn The Page,' which expresses the same attitude: how sensitive can you afford to be? If you're watching the news or reading a paper, how much can you afford to feel? How much can you get involved in the world without wanting to kill yourself immediately?

Another constantly recurring theme is trying to reconcile idealism with clear-sighted reality. I remain an idealistic person to this day, much to my pain sometimes. I grew up that way to the point where all life was then suddenly disillusioned to me. I'd imagined it as being so much nicer than it really is, and the hardness, the crassness, and the inhumanity of it all really homed in on me. It was tremendously painful, and really hard for me to face. Thus, the dividing line between youthful illusions and their subsequent loss with age is an attractive one to me. There are prices and rewards for that -- you exchange your illusions and innocence for experience and the way things really are. If you weather it emotionally, that's a fair exchange. I went through this change in a very extreme manner and a lot of the current album does face up to this dilemma.

Personally, I remain essentially an idealist and haven't been totally disillusioned. As soon as I started to realize that it wasn't a perfect world, I decided to try and make at least a part of it perfect. Yet that does become such a painful and one-sided, fruitless crusade after a while. The rest of the world is sceptical at best and usually cynical, so there has to be a meeting ground if I want any improvements and this stretches from musical morality to environmental consciousness. The song 'Second Nature' from 'HYF' expresses such a belief, because to me it seems so obvious that we should wish our cities to be as nice as our forests and that people should behave in a humane fashion -- yet this is also clearly a naïve and laughable assumption. I want a perfect world and can be bothered to do something about it, yet I can't do it on my own. So, even if you don't want the things that I do, at least let's make a deal and go for some improvement at least. But you shouldn't just scream about it in a song. If you really care about a cause then get involved with people who are doing something about it, people who are self-actuating and are actively working to improve things. That's what I do in my own time, without any clarion call for publicity. I go out into the dirty world.

On the subject of music and charities, what's your opinion on the preponderance of charity concerts across the world?

I get so impatient with the pop side of causes, the whole sensibility of, "Let's get together and change things" because these people just do not know what they're talking about and don't take the trouble to find out how they can really change something. It's a Sixties mentality -- it had no action then, and has no action now. It's just sound and fury. And, let's be honest, how many of these people are only lending their names as a career move?!

Geddy was involved with the 'Northern Lights' charity record here in Canada, although Rush weren't invited to participate in the 'Live Aid' event -- mainly because if you look at the guest list, it was very much and 'in-crowd' situation. We didn't refuse to take part because of any principles. Mind you, I wouldn't have been happy being part of this scenario. Those stars should have shut up and just given over their money if they were genuine. I recall that 'Tears For Fears,' who made a musical and artistic decision to pull out of the concert, were subsequently accused of killing children in Africa -- what a shockingly irresponsible and stupid attitude to take towards the band. But I have nothing bad whatsoever to say about Bob Geldof; he sacrificed his health, his career, everything for something he believed in. But others around him got involved for their own reasons. Some of those involved in 'Northern Lights' were actually quoted as saying that their managers told them to get down to the recording sessions because it would be a good career move! What a farce!

I don't believe that all this ballyhoo changed anything. Even now, trucks full of food are blasting through Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda, trying to get to the Sudan and Ethiopia and they're being robbed and shot at and turned back. I was in East Africa last Autumn, so I got a first-hand insight into what's going on and whilst I was there no less than 55 trucks laden with food were stuck in Uganda, with no way through because of the political situation. It's not a lack of food, nor a drought that's causing the problems, but civil war! People are starving others deliberately and how do you change that via a rock concert?! I don't decry charity causes, but if someone were to ask me to do a concert in aid of Ethiopia I'd say NO! I would quite happily donate some money or do anything else that might help, but I believe you have to get involved far more then just giving money to salve your conscience... even that type of charity is so negative because it's self-serving and shallow.

You seem to shun the usual excesses of rock stardom...

Well, I never wanted to be famous and people just don't seem to understand that. All I wanted was to be a musician, to be good at playing my chosen instrument. You read a lot of interviews with musicians who claim that what inspired them to get into bands in the first place was seeing the Beatles playing on the 'Ed Sullivan' American TV show back in the early Sixties. And I can't understand people who saw someone on TV and then decided they wanted to play music! That's so far removed from any of my responses to what I wanted to do or where I wanted to be. And my first glimmers of fame really just left me feeling that it was a weird scene. It always makes me very uncomfortable.

When I first joined the band (1974) I was totally unknown because I hadn't played on the first album ('Rush' which featured John Rutsey on drums), but there was already a fan base building so a few kids would turn up at the backstage door waiting for Geddy and Alex, and even though they weren't jumping on me because they didn't know who I was, nonetheless I felt very strange. Fame is the sort of thing imposed by the music industry because back in the Fifties they didn't know how to sell rock'n'roll music. They just looked at the way the movie industry had sold personalities by creating larger-than-life screen gods and goddesses, glamorous beings who were sold to the public as something better than they were. The same thing happened with music, and the sad thing is that the musicians went along with it. Inevitably, it led to a whole host of casualties, people like Hendrix and Keith Moon who were killed by fame because as insecure people they couldn't deal with it! All that alienation and artificial reality set up between them and the real world is frightening. Once you lose contact with reality, how on earth do you get it back? There are those whose only source of self-esteem comes from others... and then one day they look down inside themselves and it's no longer there. They've been depending on various escapes for too long and suddenly they have to face their own alienation, and with someone like Hendrix who lived a larger-than-life existence, that can be enormous. Of course, some do survive, which is fortunate, and even under the influence of drugs and alcohol and so forth they are brilliant enough to make good music, like for example Pete Townshend. But these people are rare.

In the late Seventies, the demand for us was getting ever greater and we hadn't yet learnt to say 'no' and there was a period when we had no days off to breathe. We did show after show on the 'Farewell To Kings' tour, driving ourselves everywhere; in fact we renamed it the 'Drive Till You Die Tour.' We'd play a date, drive 300 miles with no chance to rest and do another gig. From the U.S. we came straight to Britain, did some more shows and then went into Rockfield Studios (Wales) to record 'Hemispheres!' That was the turning point, we felt so much like machines, and all of us were crippled by that. In some ways the scars are still visible. The more fame we got, the more uncomfortable I became, until I had to overreact and refuse to have pictures taken or have anything to do with the machinery because it was taking over.

As a musician all you want to do is remain intact, but as a writer I needed to maintain objectivity, contact and anonymity. As a listener you learn a lot more than as a talker, yet if you're sitting with a group of people, you can't just sit back and soak up the vibes if you're the center of attention. Fame was just a negative factor on me as a person and as a professional and I had to push it all away.

I guess there is an exhibitionist aspect of me; you have to have this element to appear onstage and it comes out of me for the two hours or so that I play each night. Basically on the road, the day builds up to this and then winds down from it. Our working day is really so regular and normal in that it's and eight hour day in spite of the fact that it's not a 9 to 5 job. Still, we go into work at 4 p.m. and finish at midnight. To me, it seems so natural. I get up to go to work, do my job and then go home. But when barriers start getting thrown up around you and you start having security to keep people from getting too close then you no longer have freedom of action. You then begin to feel imprisoned against your will and feel as if you're in a fish bowl. It all begins to get a little predatory and you are the prey! Yet try to explain all these things rationally to people is impossible, because it's so far outside their experience. I don't feel I deserve all this adulation, I just do a job of work, and if you enjoy it then that's great. It's an exchange; if I enjoy doing it and you enjoy the results then that should be then end of it. You don't owe me a living, I'm not owed a loyal audience. But then the reverse is also true! Humphrey Bogart once said that the only thing he owes the audience is a good performance, but that always sounds so hard. It's fruitless to try and explain. Most of the world doesn't and can't understand.

Rush are one of the bands who do seem to command loyalty. Your audience is prepared to give you a chance with new ideas. Does this feeling take the pressure off slightly?

I think the pressure went off slightly after the success of '2112,' which was the first of our records to pay for itself. Directly prior to this release we were beginning to get a lot of pressure and thumbs were starting to come down on us trying to alter how we did things. I know that Polygram had already written off '2112' as a failure before it came out and our management were saying that we had to discuss with them the material we were using. Obviously, we were still fighting back and that album was a statement of our rebellion, but if it hadn't done well then we wouldn't have gone on.

But I think we believe that every album is gonna be the one that's gonna die on us. Something like 'Power Windows' was an especial risk because we used Peter Collins to produce it and also adopted quite a different set of aesthetics than previously. We threw open a lot of barriers and over-produced it like crazy. It could have died. Even 'Hold Your Fire' wasn't something we felt sure about, because you can so easily get disappointed. For instance, I thought that 'Grace Under Pressure' was the right album at the right time. It was a time of crisis in the world and I was looking around and seeing my friends unemployed and having a very bad time. Inflation was rampant everywhere and people were basically in trouble. The world looked dark. That album to me was a tremendous statement of compassion and empathy with the world and I thought because of this it would have a similar accessibility as '2112' or 'Moving Pictures' in their own eras. But it didn't have the desired impact because people do not wanna hear about sadness when reality is so gloomy. In the 1930's people didn't clamour for sad stories but absolute escapism and I realized that having the right feelings at the right time isn't necessarily going to be the best way of dealing with something, particularly in the so-called 'entertainment arts!'

You can never take anything for granted. Our third album 'Caress Of Steel,' was another one that was so close to our hearts, yet the public never shared our enthusiasm. So, with every new album we have a certain wariness about public reaction. The same also holds true with songs. When a track doesn't reach people it's really your fault and we've had that experience on almost every album. I think you have to say that if a song doesn't connect with people then the fault of accessibility lies with communication. 'Emotion Detector' is an example off 'Power Windows' and 'Kid Gloves' on 'Grace Under Pressure.' We did our best but didn't achieve what we wanted. You pay a price in that the song is lost and it leaves a little pang of sadness. But if I couldn't look back at songs which were unsuccessful in certain terms then perhaps there wouldn't be any chains of development of progression to other, later numbers. 'Force Ten' on 'Hold...' is an amalgamation of ideas that goes back to the last three or four albums, which at the time weren't necessarily successful. 'Digital Man' on 'Signals' was our first attempt at juggling totally disparate stylistic influences -- ska, synth-pop and hard rock and at the time we ended up with three pieces of one song held together by Crazy Glue. But we learnt from it and subsequently did 'Force Ten.' 'Countdown' is another example of a song that didn't work at the time but led us forward. It was our first attempt at a documentary, taking real life and putting it into a song. It didn't work, but led us to 'Manhattan Project' on 'HYF' which has [I think this should be 'Power Windows'] the correct balance between the music, the lyrics and the theme.

Can you ever see yourself publishing a book of verse, or even a novel?

I would like to write a book one day, but it would probably be along the lines of a travel book, influenced by the new wave of travel writers. Because with something like that you can throw in anything you want. If you want to write a poem then that can be stuck in. If you want to write an essay, a diatribe or a vitriolic defamation of character, then they can fit in as well. This kind of amorphous style makes me feel a lot more comfortable than slots do. Sometimes even fiction can be a narrow constraint in the fact that you have to carry the plot forward. And as with music, you can get stuck in a certain style with fiction. Robert Ludlow had better never attempt an historical romance, nor Stephen King a serious work of literature! The same applies of course with most music. That's why Rush has been fortunate. Form our beginnings we decided to remain amorphous. We were lucky in some respects, because every time we felt confined by being only a three-piece technology has come along and opened fresh avenues for us. Time-wise we've spanned a very fortunate era in music -- although one definition of good fortune is when opportunity meets preparation. That, I believe, certainly applies to us.

There is something strangely English about your music...

Well, our roots are fundamentally English, and as I said it was the progressive era that first got me into music -- English musicians who could play and weren't afraid to show it. In Britain the carrot-on-the-stick aspect isn't as strong as in America. For most of the latter bands it's too tempting to sell out. Even if they only play Top 40 covers in bars they make a good living. Over in the U.K. the same criteria don't apply because most acts have the attitude that they won't get anywhere anyway, so they might as well do what they want and to hell with it. Most of the adventurism that I admire in English music doesn't come from courage so much as default. Groups have nothing to lose from being as crazy as possible, of being themselves, because all they'll end up with anyway is a couple of pub gigs and perhaps get to make a demo. So many English outfits are doomed to obscurity because they have no outlets. Musically, it can lead to exciting developments, whereas sociologically it's clearly very sad.

A final question. Each year the Rush name is initially associated with the Castle Donington Festival. Would you ever consider playing it?

Well, it seems that our name is announced as a rumour every year and only then do the organizers come to us and ask if we'd be interested. The plain truth is that we'd never consider playing such an event. I've been in the audience at stadium shows and they're awful. They're also a big rip-off, with no humanity about them. It's like a mass, a mob and all they do is provide the opportunity for a lot of people to make a lot of money. One of our roadcrew freelanced for a band at Donington last year and he was telling us about the screens erected to stop missiles being hurled onstage. Why put yourself through that? We are happiest in arenas, that's our forte. Theatres are great, but only if you wanna turn around and say, "I know that 12000 people wanna see us, but the band only wants to play for 3000 kids." Who are you serving with that attitude? Who are you doing it for? All the people who won't be able to see you? For those people in the industry or with contacts to get tickets? No, we know where we are at our best and that's in arenas, where we intend to stay!