Neil Peart: Mystic Rhythms

By Tim Ponting, Rhythm, August 1988, transcribed by John Patuto

Unquestionably the most popular drummer in the eyes of Rhythm readers, Neil Peart has consistently pushed himself to the edge in his development as a musician. Tim Ponting finds out what the Rush is all about.

I had one preconception about Neil Peart before he settled into the armchair beside mine in a quiet suite in a salubrious Westminster hotel. Here was the man who had played a percussion orchestra from his drum stool on Exit Stage Left. Here too was the man I had been scrutinising the previous evening through a two hundred millimetre lens from a small pit at Wembley, thousands of screaming fans at my back. His expression, rhythmically in the first case and facially in the second, could only be described as one of overwhelming intensity - and it was this aspect of his character that was uppermost in my mind as I introduced myself.

"Last night the atmosphere was good - all of us were comfortable and relaxed."

But the look of concentration on his face sticks in my mind. Alex Lifeson says of their first meeting, "He looked weird - really short hair with shorts on. He was working in a parts department, selling tractor parts. He comes down with this small kit of Rogers drums, and played them like a maniac! He was a really intense drummer..."

"Sometimes you can never rise above that and in the whole show I can never crack a smile because I'm working too hard. But from time to time on the less focussed sections you can take note of the rest of the world - or as Bill Bruford says, 'Life beyond the cymbals'."

His quiet, deep and resonant voice belies the nervous energy evident in his live performance and taut conception of rhythmic form. Over thirteen LPs, Neil Peart has entranced listeners with the passion and intelligence of his playing, and it is these aspects of 'the professor' that were perhaps most evident in our conversation.

Before joining Rush, Neil spent some time in England working the audition circuit - a fact of which most fans are unaware...

"It was a humbling experience because I came out of the common syndrome of 'big fish in a small pond',", he explains. "I was living in a small city as the prominent drummer in the prominent band. I don't think I was particularly egotistical, but I had an inflated sense of how good I was in a naïve way - I was naïve about how much I needed to learn, I guess."

And at the turn of the Sixties and Seventies, Neil still had a long way to go. With progressive music beginning to burgeon and a new class of rock drummers emerging, some of his auditions didn't quite work out as planned. He laughs...

"I came out thinking, 'Oh God, I'm nothing and nowhere and nobody and I'll never get anywhere...'"

Neil's humbling experiences in London give a clue to the inner motivations for his now famous selection of the Ludwig drums he is presently using. Whereas most players have the misleading arrogance to assume that their initial judgement about equipment holds true, Neil's ever questioning attitude towards his own drumming has led him to reconsider the situation.

"It was mostly a reaction against the way that people usually buy drums. It seemed to me that other drummers I spoke to, and even myself, always went by what somebody else sounded good playing or what they'd been playing in the past; thinking that if they were smart enough to have picked them once, they were still that smart and the drums were still the best. Early on, they might have thought, 'Well he's my hero and he plays such and such a drum - that's what I want'. Even though it might not have suited them. For instance, I admired Keith Moon's drumming, but the first time I played Premier drums we didn't get on. The nature of their playing and their sound and response had a fluidity that suited drummers like Keith Moon and Nick Mason - the people most prominently using them at the time - but they just didn't suit me."

Setting up various kits from all over the world at the Percussion Centre in Fort Wayne, Neil blessed every drum with his own tuning and compared notes...

"No-one was more surprised than me that Ludwig was the choice. I had kind of put them in as a token American company to equal up the balance of trade." He smiles. "I had Premier and Sonor drums representing Europe, a Canadian company called Tempus (which used to be Milestone), Ludwig, and Yamaha and Tama I guess representing the Orient. I felt that I had a good worldwide balance and I was curious to see what would happen. In fact it was between Tama and Ludwig - they were very, very close."

But Neil is quick to point out that subtleties aside, any good drum is a perfectly workable instrument.

"I would have been happy with any of those drums to tour or record with. By the time I'd put my tuning into them, they were my instrument.

"I'm always a bit hesitant about endorsements because at a certain point, everyone realises that it isn't the hardware that really matters. While I was working on the Jeff Berlin project, I had nothing really of my own; I had arranged at least to bring my own snare, but it didn't turn up - nor did my cymbals. In the end I had half of a rental Tama kit and half of a rental Yamaha kit and an old wooden snare drum that was literally lying around in the storeroom of the studio, covered in dust. By the time I'd tuned it, not even with the heads of my choosing, just with what was there, it was me and I was perfectly comfortable - both playing it and listening to it."

He pauses ...

"Through the years, it has been my quest to constantly get more 'life' into my drum sound. As my ear for tuning improved, I realised that I could deal with a wilder drum, using 'wilder' as a metaphor for a kind of 'openness' of sound. I didn't need protection against overtones any more because I knew how to make them a part of the fundamental."

The quest for eternal life ...

"Yes, and it's been hard to get. The sound I was after I guess is what I used to hear as a kid on big band recordings; the days when there was one microphone ten feet away from the drums, picking up part of the brass section as well as the drummer. The brightness which that natively captured just by being in a live room with the mic far away from the drums was what I was always seeking in a close miked situation. It seemed a bit of an impossible ideal, but one worth chasing. When I went out with the Artstar I's, I was specifically after a certain liveliness that existed in my head. The change to Ludwig was just a further step in that same pattern."

The influence of big band drumming on his conception of drum sounds and playing styles is something that Neil pays tribute to in his new solo. For the first time, he has sat down and deliberately planned out its form from scratch - as opposed to his older solo material which developed during the course of their various tours or "madman's R&D labs" as Neil describes them.

"For this tour, I threw out everything I've ever done before and for the first time ever constructed a new solo from scratch. Up until this point it's always been an evolutionary process. This time I wanted to make more use of sampling, to have it as an accompaniment to the soloist rather like a percussion part. And I also had this sub theme in mind of making it a kind of history of percussion and my involvement with it - without being too pretentious about it.

"Gene Krupa was the first guy that caught my imagination. So there's a tribute to him in there, and snare drum work that's grown up out of military styles with all the rudiments. Classical percussion is represented, with tympani and keyboard percussion, together with rock drumming and jazz drumming. I tried to have a tribute or an allusion to each of those things as a part of the structure.

"I went about it just as we would build a song. I didn't want to use the linear cliché of building up and stopping at the climax - I wanted to face the greater challenge of surviving beyond the climax, to make other things happen which would feel comfortable as a denoument. It gave me great problems in the early stages of putting the solo together. I spent a lot of time by myself at the rehearsal hall working on the drum solo, finding out what worked and what didn't; practical matters such as settling when the drumset should revolve, getting the programs for the samples organised in such a way that they could be changed logically from one to the next"

The Peart solo has always been easily accessible, due to his combination of infectious enthusiasm and ready wit. There's something intrinsically outrageous about a cowbell solo at a power rock gig, a concert tom pattern based on the trumpet call that summons racehorses to the post and a bongo theme from the Flintstones. Mischief provides a welcome release for both audience and players from the intensity of their performance. But these 'releases of tension' aren't planned for either band or crowd. As Neil says, "A sign isn't flashed up on a giant video screen proclaiming 'release of tension now'.

"I've never been comfortable with the idea of pacing myself. When we first started touring and I used to talk to drummers headlining shows; they used to say, 'Well I pace myself to my drum solo'. I thought, 'No, that's not right, I want every song to be a hundred per cent'. I'm playing ten tenths from the very beginning - I worry about every single little beat and I judge and I'm hypercritical of everything that goes by. Every song that we do anyway is difficult enough that it requires that kind of focus...

"It's a question of concentration, but it's not completely inward and it's not completely linear. There are certain moments that require my utmost attention - but sometimes I'll get into the channel and my awareness expands to the other guys and beyond the stage to the audience. I'll catch a face in passing or see a cymbal moving strangely or hear something that suggests maybe that cymbal's cracked and a million little things like that - 'My feet aren't especially fluid today' or 'I've got to watch my concentration because it's not coming as easily as it should tonight' or 'This is a bad lot of drumsticks' or 'That finger hurts'." He smiles. "You have to lay yourself wide open up there on stage. You're vulnerable. I've known since childhood I have a bad temper and I have a fuse inside me that protects me from blowing up. On stage I can't have that.

"Overall, it's a very complex intensity because it's made up of so many things - partly concentration on the matter in hand but also a broader experience. Sometimes a thought will drop in from a book I've been reading, or an image from a film that I saw. It's a true stream of consciousness - your senses are intensely focussed almost like in a low grade fever. It's hard to explain ... it needs a flight of James Joyce prose to capture it."

In many ways, Neil surrounds himself with danger. There is always the risk that he won't catch that drumstick, that a particularly difficult passage won't come out on the one...

"There are moments of true fear, many passages throughout the night that are right at the extremity of my ability - some of them just a fraction higher. And in the studio, as we're working in new material I constantly aim higher and I'll blunder something through. Geddy always laughs because he wonders too - 'Is he really going to get this?'. When it comes to laying down the basic tracks, that's the most intense moment of all and it feels like the pressure of the whole world is focussed completely on me.

"I've had to learn a lot working in the studio. With clicks, you get to know where your weak points are tempo-wise and what sort of figures are likely to upset your inner pulse. You learn the little tricks of physical attitude that help you ride it out. As a band, we've learnt to share the function of timekeeping. If I'm in a difficult passage, I'll watch Geddy's feet, or Alex's feet - whoever has the responsibility for timekeeping at a particular time. If the tempo's hard to set; it falls to whoever's playing the busiest part because it's easier to keep that steady than a slow legato part. The song 'Marathon' is a good example, where I'm playing quite a slow quarter note based pattern which is very hard to sit right in the pulse - but Geddy's playing a fast and complex part, which will be uncomfortable if it's too fast or too slow, so he regulates the tempo.

"You can take the principle to a further extreme; for example in 'Mission' and 'Lock and Key', I play a solo while Geddy and Alex keep time behind me. That's fantastic, a beautiful exchange of roles: a drum solo in the terms of a guitar solo, where the rest of the band supports, Geddy and Alex playing the actual rhythmic pulse. It allows us to try out a new suit, to take on a new interrelationship between us."

With music as complex as that of some Rush compositions, it's a tribute to the talent and rapport of the three performers that things don't drift astray. But the communication between three superlative musicians is due as much to the exploratory nature of much of their music as to their friendship and skill.

"Take a song like 'The Weapon' - the drum pattern is unashamedly based on a dance rhythm, with a strong four-on-the-floor bass drum with an almost impossible syncopation between hi-hat and snare drum, which I had to learn arduously from a drum machine pattern made up by a non-drummer. I had to play the hi-hat part with my left hand and learn to cope with the syncopation in really awkward places. It was a challenge that was a pleasure to undertake, exploring new textures in sound.

"Experimentation constantly takes us into explorations of each other as musicians, and forces us into different roles. Like when we adopted 'thick' keyboards, for the first time, Alex and I related as a rhythm section. If the keyboards took the textural lead in a song, then Alex and I would work our parts out together for the first time in the way that a bass player and drummer would do. It forced him to listen to me in a new way, and me to listen to him in a new way. It has carried us forward - so that now where we need it, we automatically have the empathy."

The empathy that exists musically between Neil and friends has allowed them to develop a particularly neat approach to odd time signatures. Early experiments in polyrhythm, where one of the band is playing say a seven beat pattern against Neil's four, have been honed into a distinctive Rush trademark.

"It was originally tried as an experiment years ago on the 2112 album. There's a song called 'Passage To Bangkok', the middle instrumental section of which is in seven - but I play through the whole thing in four. It was a very blatant experiment..." Neil smiles wryly. "But in turn it has led us on to be able to use it more subtly in other songs. For example, I've found that you can play a beautiful four pattern over a 6/8 time signature. It doesn't feel like four, it doesn't feel like six - it's a combination of the two that's comfortable both to play and to listen to.

"There's a song of ours called 'Vital Signs' on Moving Pictures which is fundamentally based around a rolling sequence, so the flow of the rhythm is taken care of. Each of us could choose our own points of punctuation: Alex's guitar part is in seven laid over four, so each alternate phrase is on the up beat and then on the downbeat, just as if you were playing four over seven. So in this case we reversed it. It was an interesting way of using a new approach to an old idea.

"In 'Mission' on the latest album I play in four over the five pattern that Geddy and Alex are playing. I either pick up the odd beat when I need to or just wait until it comes around to me. It owes a lot to the R'n'B or funk idea where the pulse is most important and you want to make it feel like four, much as for instance Peter Gabriel did with 'Solsbury Hill': it's in a long seven pattern, but all the casual listener feels is the quarter note pulse. You can tap your foot comfortably to it and that's a magic thing that we've been able to learn - that these things don't have to feel odd to an audience. Odd time is not truly 'odd'; it has a lilt to it, a flow, a human cadence, but it just has to be learnt. Our audience don't know how to count out seven, but they accept that those quirky little twists are part of our music. It would be presumptuous to say that we educate our listeners; rather, we let them grow accustomed to us of their own volition."

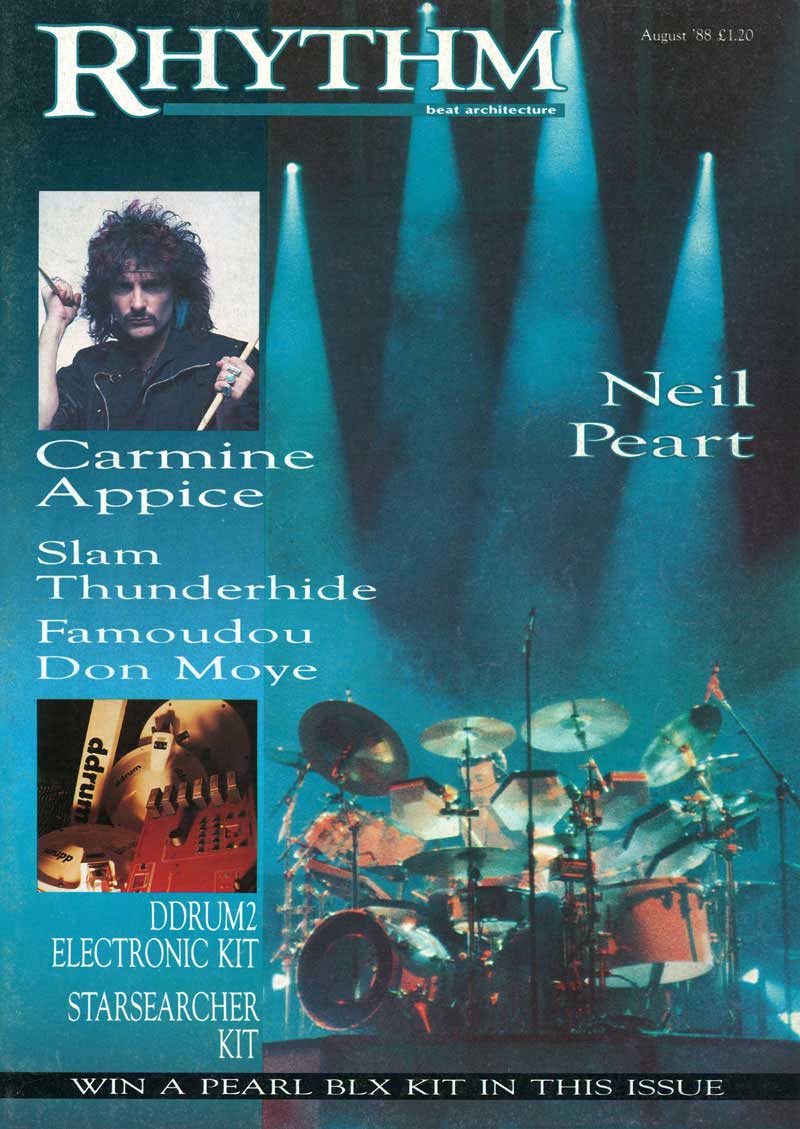

For most drummers, Neil Peart remains past master of the multi-voice approach to kit drumming. The overwhelming impression is of a man engulfed in a percussion cosmos: cowbells, a KAT MIDI percussion controller, temple blocks, timbale, crotales, various Simmons pads... The word 'panoramic' is often used to describe his breathtakingly precise tom fills. But at the heart of the kit are three elements: snare, bass and hi-hat. It is around these that the power and vitality of the Peart groove is generated. In a live situation, numbers such as 'Red Sector A' require him to stretch right from one side of the kit to the other - but the point of balance is held firmly above the snare.

"The key is to keep the centre of gravity low in your body; it's central to many mystical things in Zen meditation for instance. But people are surprised when they sit behind my kit to find how close everything is under me. I don't like to feel extended in such a way that my whole power isn't available. And if you're physically not centred then you're liable to throw off your tempo and phrasing. Having a rear kit makes a big difference; for example, I can suddenly reach two ride cymbals. There's a pattern in the chorus of that particular song 'Red Sector A' that's based upon two ride cymbals playing sixteenth notes with snare and china cymbal punctuating it. In spite of the fact that I'm spread it's still very comfortable to play.

"Even so, essentially my playing centres around bass drum, snare and hi-hat. All the other instruments are just voices that I can add. For example, there's a song called 'Middletown Dreams' that has only one tom roll in the whole song; all the fills are made up of hi-hat, cymbal, snare and bass drum punctuations.

"The early bands I was in played R'n'B and it really affected me - because that's all the drum parts are: snare, bass drum and hi-hat. I learned a lot about their rhythmic possibilities, the use of hi-hat chokes and that kind of voicing."

Neil's use of the snare in fills is very much reliant on a characteristic brightness and liveliness of the sound. Playing figures mixing semiquavers and semiquaver triplets requires a drum with crispness and definition; yet at the same time it has to be able to deliver a sufficiently hefty thwack for the backbeat. Finding an instrument to achieve that compromise is far less easier than identifying the need for it...

"That's a good point - it's very difficult to get that combination of openness and sensitivity in a snare. Ideally, you want to be able to come up from a soft double stroke roll, for instance, and still have the definition but without it choking. On the other hand, if you want it wide open and to really breathe when you smack it as hard as you can, you run the risk of losing sensitivity. I want to hear all the ghost notes, every fine definition. But at the same time there has to be a certain reverberation within the resonance of the drum to carry over too - because if you tune and damp it too tight, then all you get is very dry and uninspiring sound. I went through an awful lot of trouble trying to achieve a balance..."

In part Neil achieves this combination of guts and delicacy by playing with reversed sticks.

"Although I play with a good deal of force, the sticks are quite light so there's very little inertia to overcome. When I was first learning how to play, I used really thin Gene Krupa model drumsticks because he was my idol." Neil smiles... "I would break the tips and - of course - not be able to afford new ones. I used to tape them up as long as that lasted and then flip them over and use the other end. I soon became comfortable with that and as I moved into playing louder and harder with rock bands, using the butt end was the perfect way to get the force that I wanted without having to use big logs. And I still have the flexibility to play delicately, ghost notes, double stroke rolls and so on.

"The snare I mainly use is an old Slingerland wooden model I bought secondhand. It wasn't even the top of the line in its day! Some previous owner had made a little modification to the snare bed that just seats the snares a little deeper into the head itself. I have an exact duplicate to it which I bought as a back-up, the same model and vintage - but it hasn't that modification. It has certain characteristics in common, but doesn't have the combination of extremes that are available in the original drum which, through its innate nature and the modification some previous genius contributed, to me has that flexibility."

Neil leans forward. "It's funny we should be talking about this because I was only thinking last night about the classic Seventies slack-tuned snare sound with a lot of bottom to it. I found by experimenting with electronic sounds that it's basically just a tom-tom with snares on it. If all you're looking for is that big, fat snare sound, you might as well use an electronic snare. In certain cases I've used that, and it's been fine, but when you want versatility and subtlety, there's no way you can achieve that electronically. I guess with the variability and velocity sensitivity that's available now, it would be possible, but it would take an enormous amount of time to program all the various voices and characteristics and feels that I can draw out of a single drum. It's approaching possibility, but it certainly isn't approaching plausibility."

Neil seems somewhat ill at ease with electronics in general - right from lightbulbs to samplers. As he puts it:

"Woody Allen said, 'I'm at two with nature'. I'm at two with electronics and mechanics."

It wasn't until the advent of sampling that the attractions of the electron became irresistible...

"At that point I couldn't say no. I have a sensational desire for every percussion sound in the world: I love them all. But I'd need three stages just for me. Sampling removed the physical limitation of what I could do at one time, particularly with the KAT MIDI marimba. I've only dabbled with it so far because I just got it as we started this album. It acts as a spare trigger sometimes for effects and I've also been able to put all my glockenspiel and newer marimba parts onto it. In the future it'll play a much more important role."

Neil's desire for as complete a kit percussion ensemble as possible is mirrored by an equally strong interest in all forms of rhythmic expression. He uses a sponge analogy to describe his acquisition of styles and rhythms.

"I just soak up everything I hear. Anything new that creeps into pop music is bound to creep into my drumming by an osmosis effect. It's something that I'm far from being ashamed of - I'm proud of the fact that I'm a big fan of music and I want to respond to it and adopt every style as a part of mine. It's an acquisitiveness I guess that's, almost equivalent to greed. I've been very conscious of what the drummers of the world are doing, and I've tried to stay in touch with the most esoteric music that I can ever get to hear - whether it's from South America or China or some remote pocket of Africa. Any kind of rhythm gets my blood stirring..."

Neil's Set-Up

Drums:

Ludwig with internal Vibrafibing (addition of a thin layer of fibreglass inside the shells)

Slingerland 'Artist' snare drum

Brass plated hardware (mixture of Premier, Tama and Pearl)

Simmons pads

Akai sampler

Yamaha MIDI Controller

KAT Percussion Controller

Temple Blocks

Timbale

Set Zildjiah Crotales

Tama gong bass drum

Various cowbells and wind chimes

Cymbals:

All Zildjian (except Chinese cymbals from Wuhan province, China)

Two pairs 13" New Beat Hi-Hats

20" Medium Crash

Two 16" Medium Thin Crashes

10" Splash

8" Splash

Two 22" Ping Rides

Two 18" Medium Thin Crashes

20" Swish

18" Pang

20" Medium Crash

19" K China Boy