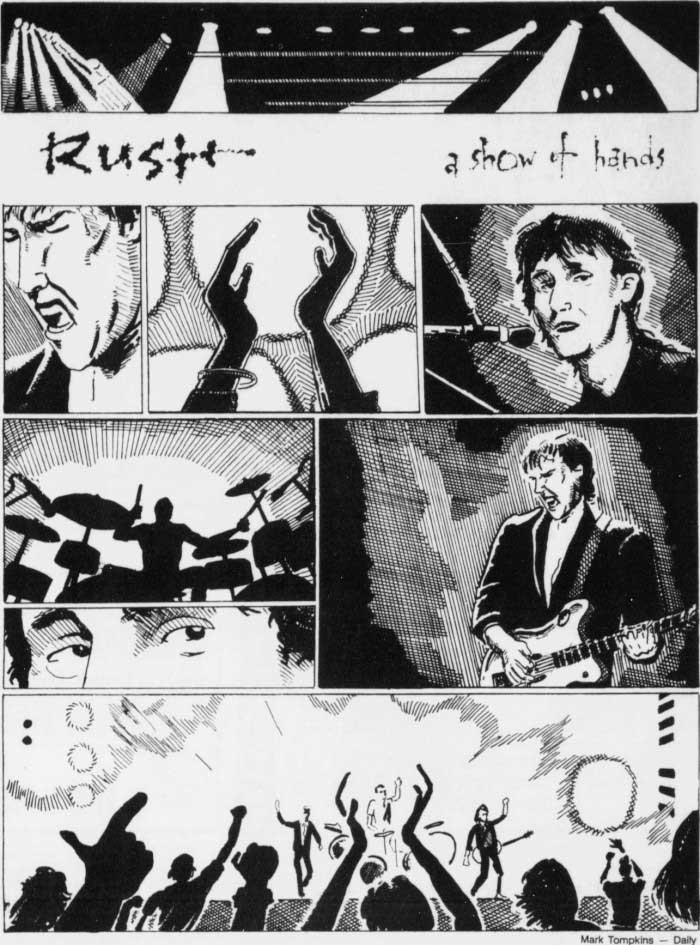

Rush's Music Is Never Dry

By Matthew Marx, illustration by Mark Tompkins, Stanford Daily, February 16, 1989, transcribed by pwrwindows

Open up the case of "A Show of Hands", pop the disc into your CD player (if you have one), and after a minute or so of fans wilding cheering on an electric organ rendition of "Three Blind Mice" you'll probably wonder if your roommate secretly switched discs with his "Sesame Street" soundtrack.

But give it a few more seconds and you'll be blasted by the steel chord which kicks off "The Big Money," the first track on the latest live/greatest hits album from Rush. Sure, it's a strange way to start off a concert album, but that's the way Rush does it. Rush has always done things differently.

Born out of the Toronto music scene in the early '70s, Rush got its start where all perfomers except Star Search finalists do, playing the club scene. In 1974 Mercury Records released Rush's self-titled debut album, instantly branding Rush as a Led Zepplin ripoff. And for good reason: just compare the guitar licks (ever lick a guitar?) in "What You're Doing" and Zep's "Heartbreaker."

At that point, Rush was made up of bassist/vocalist Geddy Lee, guitarist Alex Lifeson and drummer John Rutsey. But Rutsey didn't even stay around for the group's first official tour. (Put him in the same group of dumb drummers as Pete Best.) To compensate, Lifeson and Lee recruited Neil Peart, who would soon become the world's greatest (no, none of this "one of the greatest..." pussyfooting around, THE GREATEST) drummer. Yes, even better than Sheila E.

Peart changed Rush forever. By providing the band with his percussion wizardry he allowed Rush to develop their own unique sound.

Rush was among the first to write multiple-part (and sometimes entire-side-of-an-album) songs, with musically diverse components united by their lyrics.

Rush's sound became so unique that after "Caress of Steel" flopped commercially (but not artistically), Mercury told the band to make its sound more "sellable" (e.g. top-40 fodder) if it planned on sticking around on the Mercury label.

Rush's response was "2112," simply one of the fiercest records ever made. The 80-minute, multiple-part title satirized Mercury's attempt at manipulating the band by narrating a fictional account of the discovery of music and its rejection at the hands of society's leaders.

Immediately after "2112", the band released its first doublelength live album, setting up a sofar unbroken pattern of four studio albums followed by a live compilation.

Rush remained static for the next several years - if anything Rush does can be called static. Turning out rock 'n roll anthems like clockwork, Rush produced "Hemispheres," "A Farwell to Kings" and "Permanent Waves."

Then came 1981's "Moving Pictures" from start to finish an unrelenting musical romp. "Tom Sawyer" ... "YYZ" ... "Witch Hunt" ... titles that make pseudorock charlatans like Bon Jovi quiver in their pseudo-leather pseudo-cowboy boots. For "Moving Pictures" the band shed its multiple-part song style in favor of a more concise four to six minute song format.

The next studio album, "Signals," was Rush's first attempt in another direction. Softer and more pensive, it was scorned by critics and didn't sell too well either.

Undisturbed, Rush bounced back with the best album of their career, "Grace Under Pressure." Let's just say that with "Distant Early Warning," "Red Sector A" and"The Body Electric," it rocks!

It was then time for exploration again, so with "Power Windows" Rush delved into the risky realm of progressive rock. Interestingly, the album debuted high on the charts but sunk right away. The same went for last year's "Hold Your Fire."

Still, their third live album, the aptly named "A Show of Hands," is hot off the presses. And it's a zinger. After the whimsical intro you get 80 minutes of the best power rock money can buy.

"A Show of Hands" relies heavily on the past few albums, including four singles apiece from "Power Windows" and "Hold Your Fire," two from "Grace Under Pressure" and one from "Signals."

The best two songs, however, are from earlier albums. "Witch Hunt," from "Moving Pictures," sounds even more sinister than the original. Reaching all the way back to "A Farewell to Kings," Rush included "Closer to the Heart."

The live recording is impeccable. It sounds even better than when I heard Rush in concert last winter in Washington, D.C. One part, however, that never needs improvement is Neil Peart's drum solo. Even pared down from the 15-minute solo he played on last winter's tour, the five-minute drum cut titled "The Rhythm Method" shows the master at his best.

From here on out Rush's future is uncertain. According to Music Express magazine, the band members broke up over the summer because of musical exhaustion - they were at a loss for new ideas. But as they remixed "A Show of Hands," they found that they were writing new guitar and vocal lines as well. What does that mean? No telling, but let's just hope that this show of hands won't be their last.