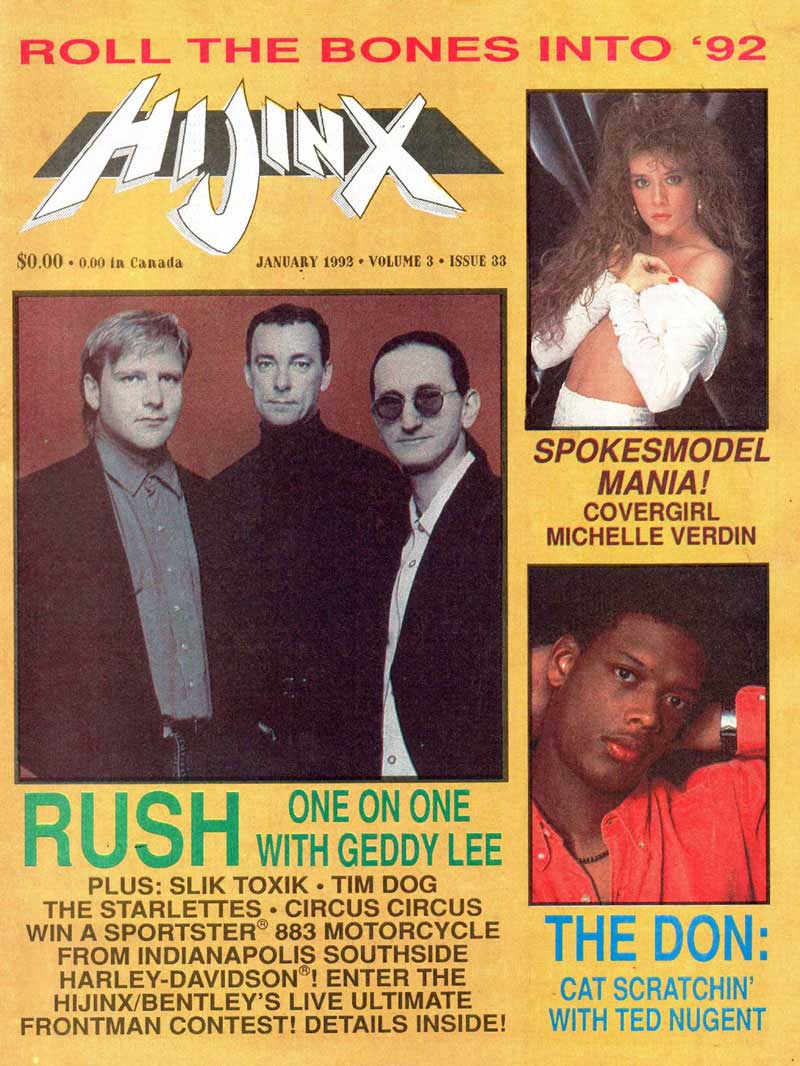

Geddy Lee On The Art Of Being Rush

By Stutz Fretman, Hijinx, January 1992, transcribed by John Patuto

THEY EXISTED ONLY TO SERVE THE STATE. They were conceived in Controlled Palaces of Mating. They died In the Home of the Useless. From cradle to grave, the crowd was one - a great WE.

In all that was left of humanity there was only one man who dared to think, seek, and love, He, Equality 7-2521, came close to losing his life for this because his knowledge was regarded as a treacherous blasphemy ... he had re-discovered the lost and holy word - I.

-from World's End, preface to Anthem, by Ayn Rand, 1946.

Fort Wayne, IN, 1976

A DIRTY-FACED KID WITH A CAN OF RED SPRAY PAINT LEAVES HIS OWN ARTISTIC MANIFESTO EMBLAZONED ON A GARAGE DOOR IN SUBURBAN MIDDLE AMERICA. 2112. the bold red letters scream of apocalyptic musical storytelling. Die in a future where humankind is washed out, impotent, vapid and in the stranglehold of mindless mediocrity. Individuality dead. Artistic expression forbidden. A new order of computer control - conformity king of the masses.

MUCH OF THAT EARLY RUSH MESSAGE was inspired by the works of modem day philosopher Ayn Rand. Books such as The Fountainhead, Atlas Shrugged and Anthem express her belief in the power of the individual artist to overcome the stagnant reproach of society huddled in anonymity. Rush turned on to Rand's resounding yes to Ego and discipline to rise above the knee-jerk attacks from a critical mass fearful of thinking for itself. So the theory goes. The ultimate struggle must be won against those lacking the fortitude to pursue dreams they are told they should never pursue because they're not practical.

In a rare look back, bassist/vocalist Geddy Lee considers the philosopher's impact on Rush.

"I think she had a great influence, her writing had a great influence on our work and it had a great influence on our lives, but more in a sense of her artistic manifesto and her belief in the ability of the individual to succeed. Art is a personal expression," Geddy says. "Art is something done to satisfy oneself as opposed to art for the people, which is kind of an unexplainable phrase in itself. Art - you set the terms for your life. You set the terms for your art. I think those kind of things in her work have affected us and probably the residue of that has lingered through the years."

Geddy is quick to point out, though, that the band has changed and grown a great deal since those days.

"Here we are, what, 13, 14 years past that point where 2112 was out and past the time in our lives where Ayn Rand was a temporary obsession with us," Geddy says. "The other aspects of her work and many other things about her influence on us have probably faded and been tempered by life, by us learning, by maturity, by being able to put her work in a broader perspective of influences. Which is I think what people go through in their lives. We're all very influenced by certain people at certain times, but hopefully that influence is tempered by the next thing that influences you and the thought that you put into it and the contribution that you make from your own sense of life and your own experience. But I think at a certain time in my life, her influences were very important and profound and they have now fallen into that great filing cabinet of influences that becomes part of your life experience."

At the time of the making of 2112, Geddy says that the band hadn't really entertained the idea of the album taking the world by storm, driving the youth to paint the town red. As a matter of fact, it was the fourth album released by the band from 1974 to 1976, coming after their self-titled debut, "Fly By Night" and "Caress of Steel."

"We were really tired when we put that record together," Geddy explains. "That was a hard record to make. We had four weeks to make it in. And we worked 20 hours a day, and I don't think you have time to stop and think of what the ramifications are gonna be. No, you don't expect that kind of thing to happen and you don't plan for it or prepare for it. You're so busy with the matter at hand, which was writing those songs and making them good and making the performances good. That's what you're thinking about and that's about it. From time to time you may have an odd second or two to muse about how the record will do but you don't know and you don't try to guess, you just do it. And do the best you can with it."

Certainly, in an incredibly successful career that's spanned three decades, guitarist Alex Lifeson, drummer/lyricist Neil Peart and Lee have demonstrated nothing but unique musical muscle and lyrical creativity. With trademark, thought-provoking lyrics and a sound undeniably its own, Rush has always been able to separate itself from the rock n' roll pack, carving out its own thinking man's niche with substance and style. The latest release on Atlantic, Roll the Bones, stands as album number eighteen. There's been a rejuvenation, according to Peart, who explains that the band members "cut holidays short" in order to put the platter and the tour together.

"We have a long creative partnership ahead of us," he announces in his "Row the Boats" soliloquy that is the band's press kit. The rekindled interest bursts through in Peart's realization in the title track: "We're only immortal for a limited time."

In standard Peart fashion, there are always some classic lines to go with the groundbreaking music, which years ago led one prominent rock mag to ask the burning question, "Is Rush too good for heavy metal?" Of course, the band has long since transcended that early label, while the drummer who's worshipped by millions of players has most certainly staked a claim as rock n' roll's number one philosopher, as well.

Take the line, "Life is a diamond you turn to dust," from "Neurotica" and Peart's explanation: "Some people can't deal with the world as it is, or themselves as they are, and feel powerless to change things - so they get all crazy. They waste away their lives in delusions, paranoia, aimless rage, and neuroses, and in the process they often make those around them miserable, too. Strained friendships, broken couples, warped children. I think they should all just stop it. That is called wishful thinking."

Geddy says the lyrical collaboration process over the years has very rarely been strained.

"It happens on occasion," Geddy says. "But for the most part we are along the same lines. The process really is quite simple. Basically, he's obviously put a lot of time and effort into thinking and writing what he's gonna come up with, so I give him the benefit of making sure that I put some time and thought into reading the lyrics when they come to me. But at the same time, he kind of uses me as a bit of a sounding board from time to time, and Alex as well. Because I have to sing the lyrics, he's very considerate of which lyrics work for me as a singer and which ones don't and he's incredibly easy to work with in that area. He has no problem changing something to suit my singing style or for the betterment of the song. And if there is something on occasion that I don't agree with, or I'm not enthused about, well, y'know, we talk about that kind of thing. It'll either get worked out or it won't get worked out. For the most part, it's a pretty communicative relationship in terms of lyrics."

In fact, in continuing a creative vibe over the course of three decades, Geddy says he and Neil often even read the same books in their spare time.

"One of my favorite books I've read this year is a book by Tom Robbins called Skinny Legs and All, which I highly recommend and actually was recommended to me by Neil. He gave it to me for Christmas," Geddy explains. "Every year he turns me on to another book that he thought was his favorite book of the year."

While Geddy says that he believes the Rand influence on the band has been "greatly over-magnified" as the band grows older, it is interesting to note that the heroine in the Robbins novel, Ellen Cherry, is a waitress/artist who's had her artistic creativity wounded by her redneck father and his rural preacher pal. Seems the two good ol' boys busted in on one of Ellen's college art classes at Virginia Tech to stop nude modeling. They dragged Ellen out screaming. They held her down, scrubbed the make-up off her face until her skin peeled and her lips cracked "like a boiled tomato." All the while the two men screamed, "Jezebel! Jezebel!" Afterward, they took her home. Of course, she runs away, leaving behind her frustrated mama, who always wished she could've been a dancer, but never gave it a shot, despite a promising start which saw her voted Grapefruit Princess of Okaloosa County at the age of fifteen.

Anyway, Ellen's haunted by the biblical image of the gory murder of Jezebel, the woman branded a whore because she wore make-up in that "great gory book, The Bible." Chalk it up to yet another struggle for artistic freedom ...

As for the ongoing Rush song writing process, there are also instances of dual interpretations of Neil's lyrics, Geddy says, and that's fine with him.

"Sometimes when he gives me lyrics, if I love it, and it could be on a completely different level than what he intended, then I don't even have to question it," Geddy explains. "If I love it then I'll just do it. I don't have a problem with it, we don't have to discuss it in detail. And sometimes down the road (we'll) find that the way I was perceiving a song was different from the way he intended. I think that's great. That really is the way rock songs should be approached by fans, too. You don't always have to get out of it what the writer put into it. As long as you're getting something out of it on one level or another."

The free exchange of ideas and artistic leeway granted one another has certainly allowed Rush to flourish as a unit in a business known for its cataclysmic breakups and reformations. It's a gift of longevity that Geddy says he doesn't take lightly. "I'm thankful that we've been able to survive as long as we have, and that we've been able to keep our friendship and our working relationship so healthy," Geddy says. "It hasn't been easy and it comes and goes. But I guess I consider myself very fortunate that I have such a good job that enables me to express many creative things and to be able to work with the same people for so long. It's a privilege to a large degree," Lee says.

It's that unity which kept the band from hiring a keyboard player back in the old days, Geddy explains.

"It's something we talked about, and to a large degree it felt like kind of an intrusion into the club," he says with a laugh. "Y'know, the three of us. It seemed a very foreign thing. And I guess we kind of thought that our fans would view that as sort of an intrusion, as well. We figured that our fans would probably stomach us wrestling with technology easier than having someone else on stage, to be quite honest."

And while the band's sound has developed over the years, becoming more complex and computerized, Geddy says the performance must still come from the three players.

"We opted for using a very complex system of MIDI sequencing and the odd sample here and there to accomplish what we do, but the justification for using that technology, for us, has to be that we have to trigger everything ourselves. It has to be part of the performance," Lee explains. "It has to be events that we stop and start, otherwise it's foreign to the stage and it's not a performance. It can't be some mystery guy turning sequencers off on the side of the stage. It has to be us doing it all."

All of which places a special burden on Geddy, who in a sense must have three brains musically, one for keyboards, one for bass, and one for singing.

"Not to mention my dancing." Geddy says.