Geddy Lee: The Roll The Bones Interview

By the Bass Player Staff, Bass Player, June 1992, transcribed by pwrwindows

When Rush embarked on its first U.S. tour in 1974, there were two people on the road crew. For this year's tour the band brought a crew of 46. Along the way Geddy Lee, guitarist Alex Lifeson, and drummer Neil Peart have amassed enough equipment to fill six semis-much of it consisting of high tech digital synthesizers and other MIDI gear. But even though Geddy commands the must silicon with his frequent moves to keyboards, bass pedals, and sequence-triggers, if you ask him what he plays, he'll tell you, "Bass guitar."

Considering the influence Rush has had on musicians worldwide, it's no wonder Geddy was named the 1991 Bassist Of The Year by Bass Player readers. lt's also not surprising that he won the Guitar Player Reader's Poll enough times to place him in that magazine's Gallery Of The Greats. Yet amidst the ever-mounting technology of today's music business, Rush decided to pare down its sound for the band's latest studio album, Roll The Bones [An-them/Atlantic]. Along with sparser, more trio-friendly arrangements, Rush is bringing a new attitude on the road: they're opening up songs, letting the studio versions serve as performance guidelines rather than mandates, and having a little more fun onstage. "With almost every song on 'Roll The Bones,'" the bassist boasts, "there's something different about the live version."

Don't expect the technology to go away, though. Rush is one of the few touring bands that triggers sequences and samples onstage without the aid of a click in the drummers headphones. This bold approach is forging a new kind of music, one where technology is important-but where live performance comes first.

In 1974, did you have any idea how far Rush might go?

No-how could I? Back then, we were so excited just to do our first tour. We never thought we'd have the opportunity to tour on that level again, let alone think about still headlining 18 years later.

How has your role as bass player changed since those days?

The interaction between Neil and myself has become a little more subtle over the years; we've acquired taste with time. But basically I think my role is the same. Bass has always been a big part of the band, and I've always tried to use it as more than just the bottom of the audio spectrum. The other guys have always allowed me to be as musically pushy as I've wanted to be. I've sometimes wondered whether l should take more of a back-seat role on certain songs, but Neil, in particular, always pushes me forward. It's nice to have that kind of encouragement.

How has your style changed?

There's a certain fluidity that comes from playing for a long time and having confidence in the things you do. You're always a little tentative pushing into a new area, but when you're doing something you know well, the confidence naturally comes out. The end result is a fluidity in the way you accomplish that particular thing.

I think the evolution of my playing has also gone hand-in-hand with my singing and my role in the band. When I write bass lines, I need to bear in mind that I'm going to be singing while play them. There's a big connection there, and I've had to write bass melodies that are sympathetic to what the vocals are doing. On the other hand, it's also great to create independence between the bass and vocals. It takes a long time and a lot of rehearsal, but the stronger you can split up your singing and your playing, the more your playing and your singing are improved.

Have you ever written something and thought, "This is great, but I'll never be able to sing while I'm doing this"?

Many times [laughs]. Even "Roll the Bones" has accents that totally go against the vocal part, although the bass line isn't complicated. That's one of the most difficult songs for me to do, because it's hard to get into those bass-and-drum punches and keep the vocal line from getting herk-jerky. The tendency is to want the vocal to push with the bass, so I try to shim the vocal a little on either side so that it works. Again, the guys have given me a lot of encouragement rather than let me settle for a bass line that maybe isn't so interesting. They've always encouraged me to go further, even though they know I'm going to have a headache at rehearsal [laughs].

When you've making a record, do you always have to think about performing the songs live as a trio?

Yes, in a sense. But over the course of the last three albums, we've gradually said, "To hell with the live thing, let's just make the best record we can make." It took a long time to say that, because we were a live band for so many years and were always paranoid of not being able to faithfully reproduce the studio sound. A lot of the bizarre arrangements of our earlier records grew out of that thinking. I'd think, "Okay, I'll put the bass-synth pedal here, and that'll give me time to change from this instrument to that instrument," and so on. On the last three records, though, we've decided to cross the bridge when we come to it. We've also loosened up our attitude about arrangements. We realized that if we change the arrangement a little for the live show, it's not a crime-people will understand, as long as it's still a good arrangement.

Have you rearranged some of the older stuff with that in mind, or have those arrangements taken their own directions?

They have taken their own directions; we haven't gone back and reviewed things. But sometimes, as we're playing a song throughout a tour, we can feel that being at a certain place at a certain time isn't so important anymore. We now think it's right to feel a looser, spontaneous, jamming sort of vibe on some of the songs-so we just let it happen. I think that's been a healthy thing, and it adds little surprises here and there to a live show; at the end of "Bravado," for instance, we stretch the ending and just jam for a while. It's nice to approach the music a little differently live. I think it's nice for the audience, too, to hear something they didn't expect-something that's not on the record.

Aren't you restricted by sequences?

We do use a lot of sequencing. The complexity of some of our arrangements, with me playing bass through the whole thing, requires it. But as long as I stay close to the pedals, I can trigger the sequences and turn them off as needed.

Do you ever use bass sequences in the studio?

Not really. There's usually one song on each album where I sequence the bass line, because it's nice to have a textural change-where you don't have that finger-on-wood sound. There's also a nice mechanical sound to sequencers that a human being can't quite capture-thank God [laughs]. On Roll The Bones, we sequenced the bass line on "Neurotica"; on Presto, it was "Scars."

You're known for using bass pedals quite often. Do you like to play them or would you always play just bass guitar if you could?

It usually seems like the pedals are a last resort, but there are times when I could be playing bass and I opt to play pedals, just because l like the dynamic textural change. On "Show Don't Tell" [Presto], I could easily play bass guitar during the choruses and trigger other things with my foot, but I really like the way the bottom end of the room opens up with those big pedal notes. Now, with samplers, I can play pedal sounds on the keyboard and I don't need to use my feet.

It seems like a MIDI-controller bass would be perfect for you. Have you tried any of the systems on the market?

No, I haven't. I think I'm reluctant to because I'm tied to MIDI everywhere around me, and I look at my bass as this analog device that I want to keep holy. I'm afraid to cross the line with it; I'd like to keep my bass my bass. God knows I'm not a purist in any sense, but maybe that little "analog sanctuary" is protecting me a bit [laughs].

For this tour, you're using your new red Wal onstage.

Yeah-I love it. It's got a slightly warmer sound than the [black] Wal I've used for the last few years. The old one still sounds good to me, but it doesn't have the depth of sound that this one has. Granted, the difference is fairly subtle, but it's enough for me to notice onstage. Unfortunately, I never know what people are really hearing out there anyway; I'm sure what I'm hearing through my monitors is completely different.

Every hall sounds different, and more often than not, the bass frequencies get lost. There are some great-sounding arenas out there, though-the Forum in L.A. is one of the best halls in the country. I also like the Meadowlands in New Jersey, and Madison Square Garden in New York doesn't sound bad.

Your tone has changed over the years. What's your idea of the perfect sound these days?

I've always liked my tone to have an edge, but over the years I've been moving the edge higher and I've brought in more warmth. When I got my first Wal, it blew me away-the lower mids are so constant and the tone fits so easily into the context of our band on record. I don't need to use a lot of fancy EQ; the bass just naturally bounces and hangs there. That's what I'm really after: the bounce of the sound. If I'm playing a lot of notes, I don't like the tone to get twangy; I like there to be a bit of depth to it. The sound I'm using on this tour is a little twangier than I'd ideally want it to be, just because in a big hall the only way you can get articulation is to sacrifice some of the bottom end and overemphasize the mids. I'm sure a big part of my sound on those older records came as a result of being in a touring band and having to use all that twangy grunge. I have a great fondness for that sound, but these days I'm looking for a rounder tone.

For your live sound, are you mixing a miked signal and a direct signal?

Yes. It's funny because live we mike for the top end, but in the studio we mike for the low end. I've always used a combination of amp and DI in the studio, but only on the last two albums have we miked the bottom end rather than the top. It makes a lot of sense, because when we record bass synth, we run the synth through an amp and mike it to get rid of that sterile sound.

What bassists are you listening to these days?

As far as I'm concerned, Jeff Berlin is the best bass player on the planet right now-an incredible talent. I also like Flea from the Red Hot Chili Peppers, and Les Claypool [of Primus] is fabulous, I've enjoyed watching Primus open for us on this tour; Les has such an exuberance and a most unusual style. I like the way he uses chords, too.

Have you experimented with any of the new techniques, like slapping and tapping, or do you feel they're not for you?

I like to play around with them, but I'm not very good at it, and I have a hard time finding a context for those sounds in our music. It's very trendy, and it's the thing for a lot of younger alternative guys. I must say, though, that when I see players do them really well, it's inspiring.

What do you think about contemporary rock in general?

I think it's a pretty exciting time. There are a few bands that are getting dangerously close to being over-hyped, but there's some exciting music coming out of the United States right now-Nirvana and Faith No More, for example, and Metallica in the metal world. And the Chili Peppers, even though they've been around for a while, have a really bold sound that's catching on. It's like another new wave, and it's nice to see it coming from America for a change rather than Engand. It'll be interesting to see how some of these bands develop, if they stay together-and I hope they do, because that's when the freshest music comes in.

Are there still new worlds for Rush to conquer?

I think so. I like the fact that we're getting a little funkier in our middling years [laughs]. Considering that we're white and Canadian, we've got a lot going against us in terms of playing any sort of vaguely funky music, but it's definitely fun to play around with.

What about side projects?

I've played on a few friends' records back in Toronto, and I've helped out some people with production. The problem is that right now, the only time I can do side projects is on my home time-and I don't want to give that up. All of us in Rush have projects we say we'd like to do once the band is all said and done, but the band doesn't ever go away [laughs], so all these projects have been on hold for a thousand years. Now, we're realizing that the band isn't going to disappear until we want it to, so we're considering taking sabbaticals and doing more side projects. But we don't want to neglect the band responsibility, and we've fought very hard to get a lot of home time and we don't want to sacrifice that either. At this point, I don't exactly know how it's going to get worked out.

In your experience, has dealing with the music business gotten more difficult over the years?

I think it's gotten easier, actually, because there's more communication now. I wish I had had all these music magazines around when I was starting; nowadays, if someone doesn't understand something about the business, they can read about it in a magazine. Over the years, a lot of musicians have signed bad deals because they didn't know better and because their managers didn't bother to educate them.

It's important not to be hasty when you're dealing with the music business. When you're young and looking for a deal, it seems as if you must sign right away, or you'll miss the boat. But you have to have confidence in your ability, and you have to be intelligent. Get a good lawyer who will give you good advice, and listen to his advice. The greatest trick of managers and record companies is to leave contracts until the last minute-they'll organize the tour and everything, and then suddenly they'll say, "Okay, you've got to sign this." Here you've struggled all your life to get on that great tour, and you feel as if you can't pass it up. But you should realize that if they really want you and you're valuable to them, they'll respect your wish that things should be done properly.

What one bit of advice would you give to a young bass player who's just getting started?

I'd tell him to woodshed-practice his ass off and get the technical thing out of the way. Once you've done that, you can be just as creative as you want to be and start developing your own form of expression.

Something Old, Something New

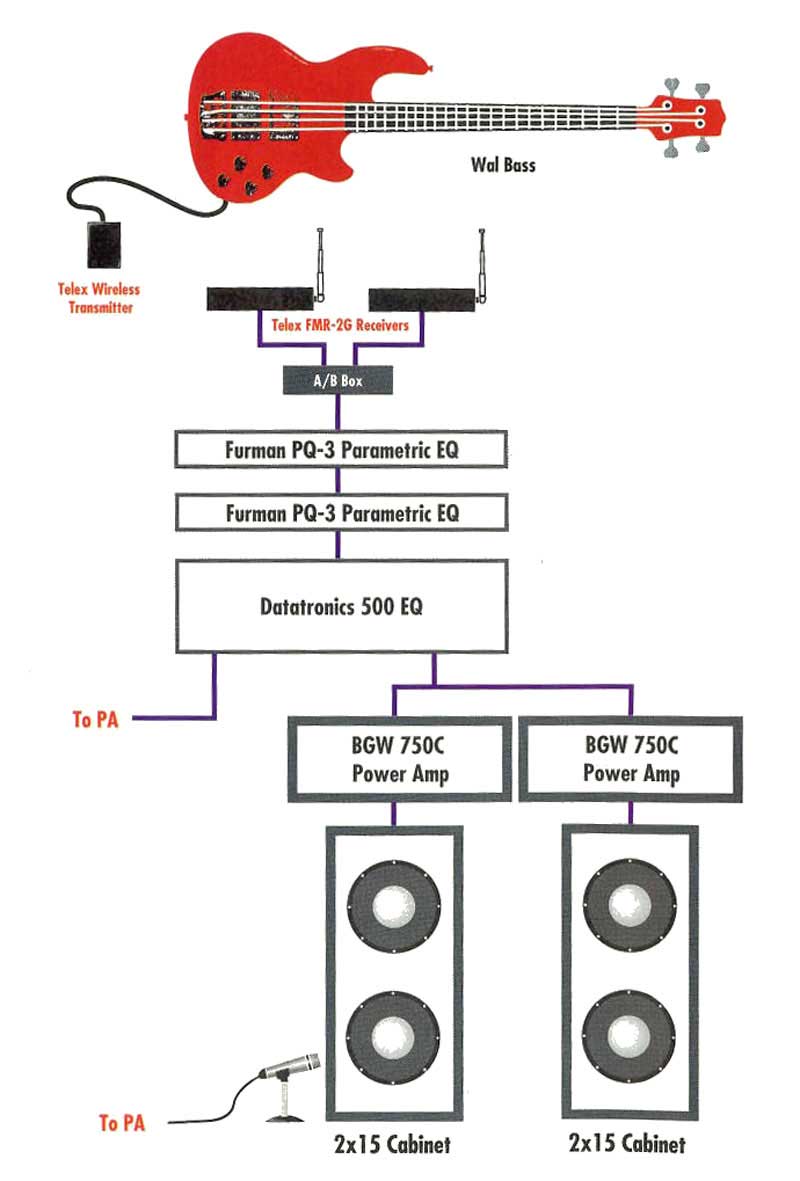

Geddy Lee's Road Rig

Few bassists use os much high-tech gear in concert as Geddy Lee. But in addition to the racks full of sequencers, samplers, and MIDI mappers, a good portion of Geddy's current stage rig consists of well-worn equipment that has stood up to the rigors of many Rush tours.

When he's onstage, Geddy hears a low-level, stereo house mix through a wireless earphone monitoring system. The band's technicians and monitor mixers all listen to the same earphone mix, and the crew can talk to band members through the earphones without reaching the main PA. The stage also has conventional monitor speakers, but these are in place only in case the earphone system goes down.

Geddy's bass sound starts with his two Wal basses. For the Roll The Bones tour, Lee has been favoring a red Wal that he got early last year; it has a slightly larger body and a deeper sound than the black Wal he's been using since the late '80s. The basses are fitted with Telex wireless transmitters, which feed two Telex FMR-2G receivers (one per instrument). Geddy's buss tech, Jim Rhodes, uses an A/B box to choose which receiver sends a signal on to the rest of the rig. Geddy's "preump" consists of a series of EQs, which boost his signal and fine tune his tune; they include un old Datatronics 500 and two Furman PQ-3 parametrics. The signal is then split; one line is led directly to the PA and another to two BGW 750C amplifiers. The amps power two 2x15 cabinets; one is miked to add high end into the PA mix. All of Geddy's gear is protected by Furman PL-8 and PL.-Plus power conditioners, which also provide lighting for his racks. Jim Rhodes tunes Geddy's basses with a Korg DT-1 PRO tuner and a Conn Strobetuner; the latter shares rack space with a replacement-parts toolbox.

Onstage, Geddy uses a Yamaha DX7 as a master keyboard controller, a Roland D-50 synth, and Korg MPK-130 pedals; these send MIDI information to the mountain of gear all stage right, which is controlled by keyboard technician Tony Geranios. This equipment includes four Roland S-770 digital samplers and two Prophet VS synthesizers. MIDI information is organized and routed with two Anatek Studio Merges and two J.L. Cooper Electronics MSB 16/20 MIDI patch matrixes; these allow Geddy to route MIDI signals to whichever synths and samplers are needed for a particular song. All data is stored on four Dynatek hard drives. Finally, two Roland M-120 mixers blend the audio signals from the synths and samplers, adding up to the classic-yet-modern sound Rush fans have come to expect.