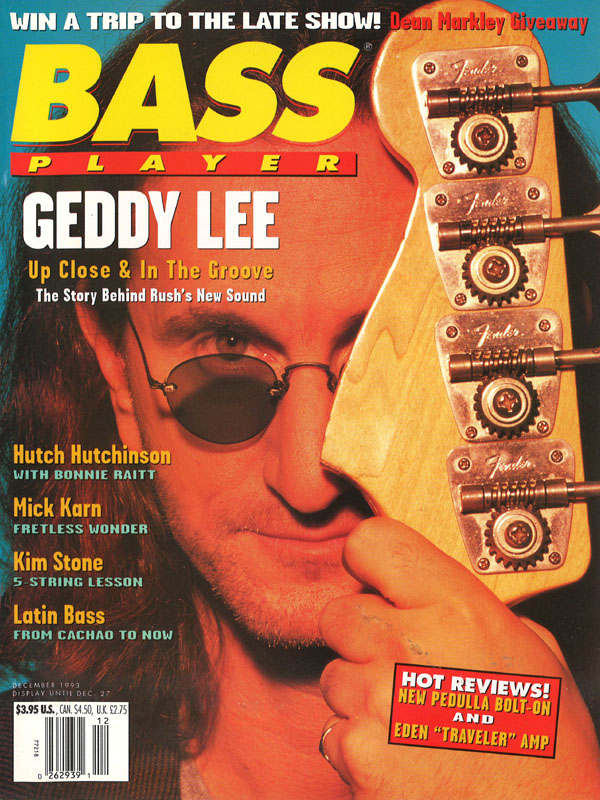

Geddy Lee: Still Going!

By Karl Coryat, Bass Player, December 1993, transcribed by David Bell

How many bands have made 19 records in 19 years, have a huge following that almost ensures platinum sales for each new album, and sell out the biggest arenas whenever they come through town?

Rush. That's about the only band that matches the description. But if you think Geddy Lee, guitarist Alex Lifeson, and drummer Neil Peart have merely learned to cash in on a tried-and-true multimillion-dollar formula year after year, you're dead wrong. Although they're as heavy as a locomotive, Rush changes direction like a hummingbird; each record explores new territories and redirects the band's sonic and musical focuses, without compromising the distinctive Rush style. Even though it's been a while since their envelope-pushing epics of the '70s, it's nice to see a veteran band alive and well rather than decaying into nostalgia and nothingness.

Take, for example, Counterparts. The latest Rush record is sparser yet bigger-sounding than their last few efforts, an approach only hinted at on 1992's Roll the Bones. Ten years ago, the band's lyrics heralded the promises of digital information and the space shuttle; this year, they lament AIDS and homelessness. It's clear Rush is in tune with the 90's.

Yet one thing has been true all along: despite the throngs of lay listeners who've stuck with Rush throughout the years, this is a musicians' band. An steady two-decades-long stream of ambitious bass-driven songs have made Geddy Lee perhaps the most admired bassist in the land. He was Bass Player's first Bassis Of The Year in 1991, and this year he won in our Reader's Poll's Rock category. (Meanwhile, Rush was voted Favorite Band and Neil Peart named Favorite Musician Who Doesn't Play Bass.) Maybe that's why, when he came to New York for a string of press interviews in support of Counterparts, Geddy gave Bass Player the first shot.

How do you account for your enduring popularity with bassists?

I guess because the music we do always seems to be "players' music" no matter how hard we try to make it anything else.

So you're always trying to expand you're audience?

I don't know if I'd say that. We're always trying different musical approaches, and we try to emphasize different aspects of the rhythm. But it seems no matter how hard we try, we can't leave the music uncomplicated. Somehow, the "player" sides of our personalities always sneak into the crafting of our records, and I think that's what appeals to a lot of young musicians.

When you're working on a new record, do you specifically try to write a hit single?

We never try to write a single because we don't know how to do it-and I guess our history proves that out. We;ve never had a "hit single" in conventional terms. We don't try to write anything but songs, and how they come out depends only on where we happen to be at, musically and lyrically, when we write them. Some songs seem to suit a more conventional approach, so we try to make those into classic tunes, both melodically and structurally. Other songs seem to require a bit more lunacy, so we don't bother with anything conventional.

The key for us is to make a record with lots of variety. That could be our bane, but it's also what makes, I think, an interesting album overall-to have a bit of everything. Because of that, we sometimes get criticized for not having a cohesive record. But at the end of the day it keeps the music interesting to make, and it offers people something interesting to listen to. That's our theory, anyway, and I guess we'll live and die by it.

What are your feelings about Counterparts?

I'm pretty pleased with it. I think it's the best-sounding record we've done in quite some time. There was a large emphasis on getting it to sound a particular way, and I think we were successful at that. Musically, there are moments I am very happy with, while other moments could have turned out differently. I'm pleased with the melodies and the melodic structures, and I think we were successful at trying a few different things.

I can't look back at our stuff and say, "I'm happy with this record," or "I'm happy with that record"-it's always a track-by-track thing. Ten years ago when we finished an album I'd love everything about it. I guess after so many years of making records, I now allow myself the luxury of being able to criticize myself. It no longer breaks my heart to wish something had turned out differently-I still appreciate that it was successful on a certain level.

Have you ever been unhappy with an album immediately after recording it?

Yes-I wasn't happy with Grace Under Pressure. But it was a no-win situation in that case because that album was extremely difficult to make. We went through tremendous turmoil and pressure making it, and I don't think I could have liked it given the circumstances. As soon as the record was done, I wanted to get away from it-and I've rarely listened to it since, because it's attached to too many difficult memories.

Ten or tweleve years ago, Rush had a certain amount of mainstream visibility you don't have now-yet your fan base is still huge.

It's like we're a big cult band. Our mainstream visibility comes and goes, depending on the particular album and the whims and vagaries of TV and radio exposure.

Would you rather be in the position you're in now or be more visible?

I'm quite happy where I am, because I can make the music I love to make, and I have a tremendous amount of freedom with it. We're able to go on big tours, and if we want to do a big production, that's possible because our shows always do well. I'm sure a lot of bands would love to have a loyal following that's always interested in whatever they happen to be up to. I'm very appreciative of our fans-especially the Bass Player readers, who have been incredibly loyal.

Do you ever feel as if you're just going through the motions?

Not when I'm writing, and not when I'm recording. Sometimes I feel that way when we're playing, though. Halfway through a long tour, there are times when I do find myself going through the motions-and that's a dangerous position to be in. So we try to stop that from happening; we organize our tours so we don't have too many performances in a row without a day off. That helps to keep us from doing "automatic" performances-we never get too slick, where we could do it blindfolded.

Will there be a tour with a big production for the new record?

Probably. It's in our nature to do it.

What steps do you go through to make the album?

We used pretty much the same approach we've used on the last few albums: what we call "boy's camp." For about two months, we go away somewhere to write, do preproduction, and rehearse. The only thing we did differently this time was we did a lot of the writing digitally; rather than go to tape, we used a software program from Cubase Audio. We write with a drum machine, just to get the arrangements fairly together, so when Neil goes to play to a song he has something fairly organized. But we had an enormous amount of technical problems, so parts of the writing process went very slowly. By the time we got to the rehearsal stage, Neil was a little short on time, and when we started to go through things with our producer, Neil was under the gun to get his parts together. He went through a massive rehearsal period; he works tremendously hard and it's incredible to witness.

After two months of that, we started recording. We transferred over the demo versions onto the 24-track, and Neil played to the demos. At that point, as always, he had his parts worked out to a T-99% of his parts were worked out, and he has about a 70% success rate at getting the entire take in one try. Neil did 11 drum tracks in two-and-a-half days. We're big believers, more and more, in rehearsing before we record-especially in terms of the "bed" [basic] tracks, because it seems the more you rehearse the faster the recording goes. Rehearsing also enables you to focus more on the performance when you know exactly what you're going to play; that way the production team can concentrate on making sure the performances are spirited and not stale.

Basically, all of the bed tracks were done in about a week. That left some time for Alex to do guitars and for me to play around with vocal ideas. We don't like to mess around when it comes time to record-we like to get in there and get it done.

Why did you go back to Peter Collins as your producer?

We recorded our last two records with Rupert Hines; they turned out great, and working with him was a fine experience. But this time we wanted to get away from the English sound we've had lately-a smaller, more layered sound. We listened to some of the records that have been made in America over the last few years, and they a bigger, bolder, more exciting sound, and that was the direction we wanted to take. At the same time we didn't want to work with a producer who wasn't a "song" person. It would have been easy to grab an engineer and say, "Let's make a record." But if you do that, you're cheating yourself out of the extra objectivity a non-engineer producer can bring to a project-someone who keeps his focus on the songs and the performances and who isn't caught up in the technology.

We enjoyed working with Peter before [on Power Windows and Hold Your Fire], but back then he was primarily a pop producer, which was foreign to us. Since then he's been living living in the U.S., and he's been working with a large number of heavy bands whose music has more to do with ours, so we were intrigued. We;ve always kept in touch and were looking for an opportunity to work together, and we decided to try it this time. I'm glad we did.

Since we had a certain sound in mind for the record, Peter helped us to go on a search for the right engineer. We listened to hundreds of tapes trying to find the right guy. And, for the first time, we used one engineer to do the recording and another to do the mixing. We wanted to bring in someone fresh-a "mixologist"-and see how it benefitted the record, just for our own education. It worked great.

The recording engineer ended up being a South African named Kevin "The Caveman" Shirley. His name says it all; we were after bold and organic sounds, and he was the man for the job-he has brilliant miking technique and a great ear for natural recording. When it came time to record my bass, I had all of these amps lying around. He pulled out an Ampeg head someone had resurrected from the garbage, plugged it into some Trace Elliot cabinets I had, and went out there and insisted on EQing the amp himself. He cranked the shit out of it and miked the cabinets in a way only he knows. I also had a DI going through a Palmer speaker simulator into the console. I used a mix of the two; when we wanted a more in-your-face bass sound, with less air and distortion, I would use just the DI track. On one, "Animate," I used just the amp, which got the sound really pumping and funky.

Kevin also talked us into using techniques we hadn't used in years. He had Alex play in the studio instead of the control room, to get that natural resonance happening between hus guitar and amp. He also got Alex to bypass all of his effects-just his guitar straight into Marshalls and other amps. And on every track he had me use my early-'70s Fender Jazz Bass, which I hadn't played in years.

Why the Jazz?

Peter first suggested it when we were discussing the record early on. We were talking about the sound we wanted, and he told me it might it might be a good idea to a bass without active pickups, to get a more aggressive sound. I thought it was a great suggestion-and I like changing basses every couple of years, anyway. So I started to use it when we were writing. Alex, who does all of the engineering during the writing stage, got a great sound from the bass and I was happy with the direction we were going with it. From then on, there was no turning back.

We were really after size when we made this record. Rather than use the SSL console to record all of the instruments, we used an old Neve console; almost all of the things that required decent bottom end went through the Neve. We always had the old technology and the new technology running simultaneously. We walked that line all the way through the record, even on the final mixes. The mixing was done by an Australian engineer named Michael Letho, who brought in a different kind of sophistication and put everything into its proper hifi perspective. All of the tracks were mixed to DAT, but one tune, "Everyday Glory," ended up being an analog-tape mix. For the last few years I've mixed only to digital, because I figured it was just a better tape recorder. But certain songs have a heavier midrange content, and on playback the analog recorder softens the midrange a bit, giving it a more likable sound. It's not as efficient-sounding in terms of the top and bottom end, but it's nicer to listen to.

How did you approach the bass playing? Did you write more songs on bass?

Many of the songs were written on bass, and a lot of them began with just bass and vocals. I tried to use a much more rhythmic approach this time. I've enjoyed listening to Primus, the Red Hot Chili Peppers, and Soundgarden-bands that have a more active rhythmic role coming from the bass. That's a direction we started going on Roll the Bones: trying to use a bit funkier approach to rock and trying to make it more groove-oriented. As a bass player, I wanted to push myself in that direction, also.

When I try to lock into a more repetitive, groove-like thing, I've found it's not about playing fewer notes-there are still the same number of notes per bar-but there is less of a variety of notes per bar. I had great fun doing the Counterparts bass tracks because of it; I felt like I was learning something all over again, and I was able to use things I already knew but applied in a different way. And I got a lot of support from Neil in that direction; he got right into it as well. I'm looking forward to playing these songs live. Of our last five or six records, this one will be the most fun to play live.

How do you come up with a set list these days?

It gets harder and harder every time. Coming up with the set list for this tour is going to be a nightmare. I imagine, because we're coming up on the 20th anniversary of our first record, we'll try to include as many songs from as many albums as possible. It remains to be seen whether we'll pull it off.

As a bassist who plays a lot of notes, how do you make your parts fit?

I think the bizarre nature of our music allows for more notes. First of all, we have a hyper-active drummer, so it makes for a busier rhythm section. When you think of Rush, you don't think of a sedate rhythm section. I have to say, though, that over the last couple of years, Neil has learned more than ever how to exercise restraint. He listens a lot more to the vocals now, and he tries to stay out of the way. He also has more respect for how important it is to give freedom to the vocal line, and he understands there's a time and a place to do the things he does. We try to hold the "chops" side of our music in reserve and save it for the appropriate moment. But we always allow for that moment to exorcise those demons, and when the moment comes, we let it rip. That way, if there's a tune that's a little more reserved and we get frustrated about not being able to smoke on our instruments, we can think, Hey-there's this song coming up and we can play like maniacs then.

You must occasionally hear tapes by young players whose bass playing really is excessive. How would you convey to a player like that the idea of taste?

I would tell him to figure out what's the essential thing that's selling the song-what is the heart of the song? Is it the vocal performance? The guitar part? The rhythm section? The lyrical concept? In every tune, there's something that makes the song, and every other part has to serve that element. If you're having trouble figuring out when to be busy or what's wrong with the arrangement, try to boil it down to the one element that makes the song potentially great and build your arrangement around that.

Over your career, what qualities do you think you've developed most?

I guess it would be knowing when to groove and bite my tongue-when to stay out of my own way. Sometimes I view my job as being the element that keeps the rhythm section smooth, that tries to make it feel groove-oriented. Early in our history, the groove wasn't so important; a lot of the stuff we wrote was intentionally herky-jerky, with shocking changes of meter and things like that. But over the last few years, we've been trying to make music that has a little soul to it, and I view my role as smoothing out any rhythmic things that are uncomfortable-to make the rhythm section sound more fluid and glued-together.

Do you agree with players who say the groove is sacred?

Yes, but it also depends on where you are-what stage of development you're at and what kind of music is turning you on at the moment. Sometimes it's not the groove you're going for; it's more math. At some point you have to appreciate that certain musicians get turned on by playing with the math, and that's okay.

There are people who'd say that kind of music isn't as valid.

It's perfectly valid. If you think it's valid, it is, and that's all that counts. But that doesn't mean anyone else is going to like it! You may or may not make a living at it, and you may not turn on anyone else besides yourself. If you're going to play with math, do it because you love to do it-not because you expect anyone else to dig it. But if you want to make music that comes from any other part of your body than your head, you have to serve the groove.

What have you been listening to in recent years that's made you appreciate the groove more?

I think it's just happened. I've been listening to a lot of different things-like old blues records that really don't have much of a groove. I wouldn't say there's one thing that's made me want to play in the groove; it just feels like a natural place to arrive at as a musician.

I like an incredible variety of stuff these days. Les Claypool's playing really turns me on; I think he's got a great sense of rhythm. I also like Dean Garcia, who plays in Curve. he's got these zooming bass parts that fly around and are very interesting melodically, and there's a lot of passion to his playing.

Do you find it easier, now that you're playing more groove-oriented bass lines, to sing and play at the same time?

Yes, to a certain degree. But I still have to go through that process of training myself separately. I first make sure I've got the bass part down, so I'm not struggling. Then I start singing, and it just takes practice-doing it over and over again. Eventually, I get locked in.

How do you get your voice ready for a show?

On our last tour, I noticed I had to spend at least 20 minutes warming it up. I don't do it in a brutal way, as I used to do when I was younger; it's more of a stretching exercise, like what you do before you play tennis or whatever. I start by singing scales, very easily. Then I sing to a tape, without vocals, of three or four of our songs with parts in different ranges. That way I warm up in a more realistic and less boring way than singing only scales. Warming up makes a tremendous difference, and when I hit the stage my voice is open. What I gain in the front end of the show I lose in the back end, because after two hours my voice is tired. But I feel a lot more comfortable going into the show, because I have much more control.

I don't like to warm up for recording, though. Funny things happen to your voice when it's not warmed up, and sometimes if it's not fully open it has an appealing character you want to capture on tape.

Why does Neil write all of your lyrics?

For one thing, Alex and I are lazy. Neil has done such a good job over the years, we feel as though anything we came up with would be crummy. But if we have ideas for songs we jot them down and see if Neil can use them.

You used to write lyrics.

I wrote all of them years ago, but that was mostly out of necessity. I didn't know what the hell I was doing. It was like how you got into a band-four guys would get together and someone would say, "Okay you play bass, you play guitar...." That was what it was like for me: "You're the singer, so you write the lyrics." Our lyrics in those days, though, were meaningless-they were just teenage angst words, that sort of thing. Now, when I try writing lyrics, I find I have a lot of things I want to say, but they always come out sounding a little naïve. So I turn them over to the prof and let him polish them up.

How much do you involve Neil in the writing of the music?

A lot. Alex and I do the bulk of the writing, but Neil's ear is invaluble to us. He comes in and tells us if something's wrong or if one part could be used somewhere else; he makes great suggestions. In the same way, we act as a soundingboard for his lyrics, and he and I work closely ironing out the meter of the words. As a singer, I get pleasure out of working with him because if I'm having a problem getting emotional value out of a line, he doesn't hesitate to change something. Up until the point when we're recording the final vocal, he listens to how I'm singing the lines and makes suggestions for changes. There's no ego involved; he's a consummate professional and he accommodates me as much as he can without compromising the intent of the song.

Some of Rush's strongest tunes are your instrumentals. Would you ever consider doing an all-instrumental record?

We get more and more people responding to our instrumentals, but I don't think so-we always have to be shooting off our mouths about something. The instrumentals are great fun to do, though, and they're easy; recording them is like recess for us. We always try to save one slot per album for an instrumental; the one on Counterparts, "Leave That Thing Alone," turned out particularly well.

You were taking piano lessons a while back. Did you keep up with them?

No I didn't. I wish I had, but I got busy and one thing led to another. With that instrument, you have to be very dedicated-especiall an old dog like me. I found I had to be extremely disciplined, but my life was too busy and I started losing the ability to practice the way I wanted to. I hope it's something I can pick up again when things slow down.

Also, my motivation has gotten away from keyboards and back to bass, so I can focus more on playing bass. When I was in the keyboard mode I found I was taking my bass playing for granted; I went through a period when I didn't grow that much. Now that I've narrowed my focus, I think it's helped my playing.

Where do you want your bass playing to go?

I just want to get better-to be able to groove better. My ultimate goal is to be able to have all of these abilities at my disposal-where I can fit into any musical circumstance and draw upon any necessary style. I've always liked playing aggressive music, but it would be nice to get a combination of groove and dexterity and still maintain a melodic sense.

In your off time do you work on your playing, or do you just want to get away from it?

To a large degree I walk away from music. After spending seven months touring, I can't even look at my bass. A lot of the musical development I do is in the course of a tour-that's the greatest opportunity to improve. Not only am I playing regularly, but there's a lot of dead time when I'm sitting around, and that's good time to work on my chops.

What do you do in your off time?

All kinds of stuff. I travel, I play tennis, I go to art galleries, and I go to ball games. And I spend a lot of time with my family. My wife and I have taken up cycling; we try to stay active.

How would you like the Rush saga to end?

I don't know. Hopefully it won't be because there's a million people out there saying, "Go away!" Instead, I'd like the decision to come from us. I'd like it to be a situation where the three of us look at each other and say, "You know, it's been great. See ya." I don't know how long we can go, and we don't think about it anymore-we just take it one album at a time. I have a feeling we'll know when when it's time to pack it in, but hopefully there are still a few records left in us.

After so many years of continued success, what's kept you from resting on your laurels?

It's just not interesting to keep doing the same thing from record to record. I'm always looking back on our last album and thinking, I'm not happy about this, that, and the other thing. I guess as long as you keep being unhappy in one way or another with something you've just completed, it gives you somewhere to go.

We always feel as if there's a better record in us, so every time we go into the studio, we try to make that perfect record. But we haven't made it yet, so I guess we'll keep trying.