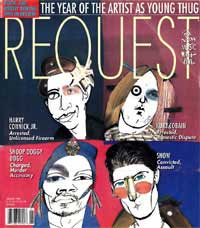

Rush Reconsidered

By Jim DeRogatis, Request, January 1994, transcribed by pwrwindows

What Once Was Pretentious Art-Rock Has Become Fodder For Primus And A New Generation Harboring Bass Desires

Their Fans Have Taken Them Seriously For 20 Years. What Have Lazy, Ill-Formed Critics Been Missing? Jim DeRogatis Opens The Band's E-mail To Investigate.

WEEKS BEF0RE THE official release of Counterparts, Rush's 19th album, analyses of the new lyrics and music are already filling The National Midnight Star, a computer fanzine on Internet. The fanzine/bulletin board serves as a sort of electronic clubhouse for serious Rush fans, a group that makes Deadheads look like amateurs, The E-Mail postings are filled with discographies, re-views of every show the band has played, and trivia about the musicians and anyone who's worked with them. All of this is treated as a science, and fools are not suffered lightly.

"I know that it's fun to come up with pet theories for how things are related to each other, but please don't send them to me saying that, 'It can't be a coincidence!'" Editor "Rush Manager-Syrinx" cautions in an introduction to a recent edition of The National Midnight Star. "Send a reference to an interview or a quote from a band member that supports what you say. For example; Don't point out that 1 [the scanning code on the back cover of Counterparts] [sic] is the binary equivalent to 73 deci-mal, and 73 decimal is ASCII for the letter 'I,' and the letter 'I' was significant to the plot of Ayn Rand's Anthem, and Neil Peart read lots of Ayn Rand, therefore [the song] 'The Body Electric' is a reference to Anthem. Believe me, you won't be the first. But Neil has never said anything on that particular subject, as far as I know."

Naturally, Rush's following is broader than just the faithful who enjoy such detailed discourse: There also are dabblers drawn to a particular album by an AOR hit or MTV video, as well as a contingent of alternative-rock fans who, thanks to Lollapalooza headliner Primus, are coming out of the closet and admitting they like Rush too. ("The new revisionist Rush theory," bassist/ vocalist Geddy Lee says.) But the true faithful run out and buy each new album as soon as it's available: When Counterparts was released in late October, it debuted at No. 2 on the Billboard album chart, trailing only Pearl Jam's Vs.

The faithful will never come right out and admit that Rush's last couple of studio albums-1991's Roll the Bones and 1989's Presto-are downright stinkers, but they are excited that Counterparts is a "return to form." When Rush started in Toronto in 1974, it mixed the musical and lyrical complexity of progressive rockers such as Yes and Genesis with the drive of no-nonsense heavy metal, resulting in such overblown but endearing high points as 1976's 2112 and 1978's Hemispheres. While the band hasn't exactly gone back to those days, it has abandoned the digital sheen and layers of keyboards that characterized its work in the late '80s, returning to the basics of guitar, bass, and drums.

Of course, the basics for Rush still mean Byzantine chord progressions and guitar solos, florid lyrics delivered with Lee's trademark Donald-Duck-on-helium yelp, and time signatures that require a degree in mathematics. But there's no denying that songs such as "Animate," "Stick It Out," and "Nobody's Hero" are more driving and catchy than anything since "Tom Sawyer" or "Red Barchetta" from 1981's Moving Pictures, which remains the group's best-selling album. The band credits the success of Counterparts to a more organic approach in the studio.

"It was the first record in a long time where we clearly knew what we wanted it to sound like," says Lee (real name: Gary Lee Weinrib, according to the computer fanzine). "It was kind of nice to get back to more of that youthful energy of playing," says guitarist Alex Life-son (real name: Alex Zivojinovic). "It wasn't a complete reinventing of the band by any means, but we did change the wrapping) concludes lyricist/drummer Peart (real name: Neil Peart, though the pronunciation is "Peert," not "Pert").

The band members (who were interviewed separately while in their offices at Anthem Entertainment) agree that the impetus for change came from a 1992 tour with Primus, the San Francisco Bay Area trio that retooled Rush's prog-rock for the thrift-store/grunge crowd. Rush also was inspired by the energy of the new Seattle bands, especially Pearl Jam. The situation recalls the way punks in the late '70s prompted the first generation of progressive rockers to strip back the excess on such relatively lean-and-mean albums as Yes' Going for the One and Genesis' . . . And Then There Were Three.

"When we went in to do this record, Alex and I were sitting at an eight-track computer machine getting ready to write and watching everybody set up the keyboards," Lee says. "When they were done, there was this bank of keyboards with all these television screens, and nowhere could you get a ball game. We just went, 'Pass.' Inevitably, you come back to these machines to add something later or make the arrangements more interesting. But I think we proved to ourselves that the best way to write is not to rely on these machines first."

Producer Peter Collins, who worked on 1985's Power Windows and 1987's Hold Your Fire, and engineer Kevin "Caveman" Shirley, a newcomer who owes his nickname to his analog attitude, encouraged Rush to think like metalheads. "This was the first time in 12 years that I sat in the studio and recorded guitars," Lifeson says. "I'd been sitting in a very controlled control room where communication is instantaneous and your monitors always sound great and everything's nice. I got talked into going out into the studio, and then I realized, 'This is where it's at!' You've got to feel the guitar vibrating against your body and the sound going through the pickups for you to lock into the energy and really push it."

Lee says that Presto and Roll the Bones suffered from a "drastic change in writing at the same time we changed production teams; we only got it right part of the time, and a couple of the songs were shortchanged." But Peart, by far the trio's most humorless and didactic member, maintains that everything on those albums was necessary for the band's growth. "You can't change any part of a progression without changing the outcome, that's what people constantly forget," he says.

Peart is the only member of Rush with a noticeable Canadian accent, and the pitch goes up at the end of his Sentences just like Bob and Doug McKenzie. "Rush by design is a very uneven band," he says. "No way are we going to create a perfectly crafted record in which every song comes out the same, because it would mean mediocrity. It's like the Somerset Maugham quote: 'Only an average man is always at his best.'"

Peart is a curmudgeon when it comes to discussing the band's early albums. "Certainly there are a lot of people who hate all of our early records, and I would count myself among them," he says. He and his handlebar mustache joined the band in 1975 after the departure of its first drummer, John Rutsey. It wasn't long before he also became the lyricist.

"The job was kind of thrust on Neil: 'You talk good, you be lyricist,'" Lee says, laughing. "A lot of his early lyrics were quite wordy and dense and without much room for me to be too flexible melodically; it was kind of 'words per minute.'As he's become an improved lyricist-and some of his lyrics are fantastic now-the style has changed, and he's written with my consideration in mind." If Peart isn't actually embarrassed by the lyrics of old gems such as"2112" (with its sci-fi tale of the priests at the temple of Syrinx) and "'The Trees" (a parable about the need for unity between maples and oaks), he does seem chagrined that the faithful continue dissecting them on a computer bulletin board. He'd much prefer that fans put their efforts into analyzing his recent efforts, and many do.

"Had an interesting discussion with a friend of mine the other day about 'Heresy' [from Roll the Bones]," a Rush fan named Steve writes in The National Midnight Star. "It appears to me that Neil is blaming the Soviet military buildup (communism/collectivism) for the 'fear and suffering' that both the Russian people and western cultures experienced during the Cold War. My friend believes that Neil is blaming the American government as well for overreacting to the Soviet threat: 'All a big mistake.' It seems to me, evidenced by previous songs, that Neil views the threat of collectivistic totalitarian governments very seriously; it's certainly evident throughout '2112,' 'Red Sector A,' 'Red Lenses,' and 'The Trees.' Any thoughts on what the 'big mistake' is? Is it communism/socialism or paranoid capitalists? Maybe both?"

"The lyrics are as much of an attractor as the music," says Deena Weinstein, a sociology professor at De Paul University in Chicago who has written about Rush in two books, Heavy Metal: A Cultural Sociology and Serious Rock: Bruce Springsteen, Rush and Pink Floyd. "The lyrics speak to people, and God, do I know these people. Every last one of them goes to college. They're not party animals; these people are really well-read. They think they should know some philosophy, and they've read some philosophy. They're not slackers at all; they're the antithesis. They're really serious about existence."

Almost all Rush loyalists are male. It's impossible to decipher their average age from the computer bulletin board, but many seem to be stuck in adolescence, at least when it comes to dealing with the opposite sex. Their messages are filled with dumb, awkward sex jokes, and there's even an abbreviated Beavis-and-Butt-head-as-computergeeks code: GMAW means "gave me a woody," ISTBO means "it sucked the big one," and TOS means "totally orgasmic shit."

The guys on the bulletin board will have a field day with Counterparts, which is essentially a concept album about male/female relationships. "Gender differences were a big subject of study for me in the last two years," Peart says. "I ransacked everything from Scientific American to what the great thinkers of the world have had to say about it, just so I can be clear on what I was thinking and then try to put it into a few words."

The result is songs such as "Animate," in which Peart calls on the "Goddess in my garden/Sister in my soul/Angel in my armor/Actress in my role" to "Polarize me/Sensitize me/Criticize me/Civilize me." Peart boasts of putting months of research into the 200 or so words in each of his songs. He claims he read 12 books about nuclear fission to write "Manhattan Project" on Power Windows. For Counterparts, he immersed himself in the writings of psychologist Carl Jung and controversial anti-feminist Camille Paglia.

"I don't agree with everything she says," Peart confesses. "But when she quotes Freud and gets in trouble for that, she says, 'Look, I don't believe every word the guy wrote. He had some good insights and I choose to make use of them.' And that's the same way I feel about Camille Paglia and Ayn Rand."

But Paglia, Rand, and Peart are all prone to being misinterpreted by their devotees. The theme of maintaining one's individuality-either in society or in a relationship-is key to all of Rush's work, Peart is firmly on the side of the individual, and he has described his political leanings as "left-wing libertarian" But Weinstein cites as an example how many fans think that Rush sides with the priests in the temple of Syrinx in "2112," even though Peart's priests actually are fascists who are trying to stamp out self-expression. Other fans seem to confuse Rush, the group, with Rush Limbaugh, the No. 1 enemy of "political correctness." Callers to a Chicago-area radio show said they believed that in the song "Nobody's Hero" Peart was saying he was tired of seeing the media portray people with AIDS and women who'd been raped as heroes. But the drummer says he meant exactly the opposite: The two people portrayed in the tune "were more important in my life than any of the 'media heroes.'"

"Why are people expecting super-human, non-biological functions from their heroes?" Peart continues. "People like film stars or Michael Jackson or Michael Jordan are somehow above any earthly taint. Obviously it warps them out, but it's also very unhealthy for the admirers."

One could argue that die-hard Rush fans view their heroes in a similar light, "Rush fans perceive Rush as these real godlike figures: 'Neil the super-intellectual lyricist and master of the drum kit,'" says Andrew MacNaughtan, the band's photographer and personal assistant. "I think because they're such perfectionists in everything they do, they're perceived as being perfect and they can't do wrong. The band has a hard time understanding why the fans are so-I don't want to say psychotic-but just infatuated with them. They appreciate it and they thank their fans for it, but they just don't understand why some fans go too far."

Going too far means showing up at the band members' homes in rural Toronto suburbs and peering in the windows, MacNaughtan says, which is how the photographer himself met the band. As a teenager, he ran a fan club called the Rush Backstage Club of Toronto, and one day he turned up on Lee's doorstep. "He said, 'I'd appreciate it if you didn't tell anybody where I lived. You're a polite boy,"' MacNaughtan recalls. The photographer went on to found a Toronto music magazine; Rush bought some of his photos for the Power Windows tour book, and that led to a full-time job at Anthem. The band didn't even know about the old fan club until MacNaughtan brought Skid Row singer Sebastian Bach (a former member) backstage during the Roll the Bones tour. "Bach didn't waste any time telling Rush that l used to do a Rush fan club," MacNaughtan says, laughing.

MacNaughtan characterizes the band members as intensely private individuals who disdain the trappings of rock stardom, including videos, photo shoots, and interviews, He says they all have healthy senses of humor, and he has tried to capture that in his work: The CD booklet for Counterparts features a photo of Peart at the end of the '92 tour sitting on a toilet displaying a mohawk haircut that MacNaughtan had just given him.

But the photographer says the faithful rarely pick up on the humor when they meet their heroes. "They're not perceiving Neil as he should be perceived: as a human being, as a funny, goofy guy, and as an intellectual," MacNaughtan says. "Neil knows everything about everything; art, history, literature. Of course, a fan will never know this."

"The horror of being the object of such obsessiveness must be enormous, especially given where Peart is coming from-the individual attempting to work with integrity," Weinstein says. One might assume that knowing beforehand that the faithful will deconstruct every rift and word on an album would weigh heavily during the recording process. But Peart, Lifeson, and Lee say they barely think of the fans. Their attitudes about their following vary dramatically, offering insight into the band members' personalities.

Lee is bemused by it all. "Every once in a while you get the overly intense Rush fan who has come to know you, and it's a little scary," he says. "But for the most part, they're pretty considerate, polite, and introspective. They're very intense, usually, and very enthusiastic. But I think fans of anything are like that. I'm a baseball fan, and I'm pretty nutso. If you ran into me at a ball game, I'd be pretty hyped-up."

Lifeson is almost paternal. "I think our audience is into the band as much as we are, and they take as much time and care with our music as we do," he says. But Peart says he rarely recognizes anything of himself in his admirers. "How much commonality can there be?" he asks. "People find what they want to find or approach our music from many different angles."

Like "Rush Manager-Syrinx." Peart dismisses anyone who can't back up his or her views. "The problem in a democracy is you get a lot of uneducated opinions with all the strength and fanaticism as if it were revealed truth." he says. "When I get an opinion from someone who's done research for a long time, I take that with a lot more weight than someone who listens to a talk show on the radio and says. 'Wait. that's not right.'"

For Peart, this is as true in rock 'n' roll as it is in politics. He believes that because he's played drums for 30 Years, he's more qualified to judge what constitutes good rock music than any critic or fan. The fact that a lot of people disagree with him despite his obvious expertise is one of the factors that drew him to Paglia.

"Her odyssey has been much like mine." he says. "She came out of '60s feminism, so her credentials are sound. Then her study, basically 25 years of scholarship, led her to certain conclusions that people dismiss with a snap. She spends years and years studying something and then says, 'There's this and this difference between males and females,' and somebody says, 'No there isn't.' This bothers me, too. If somebody's not willing to do the homework on it, then they have no right to the opinion. As Joe Walsh so eloquently put it, "There's just no arguing with a sick mind.'"