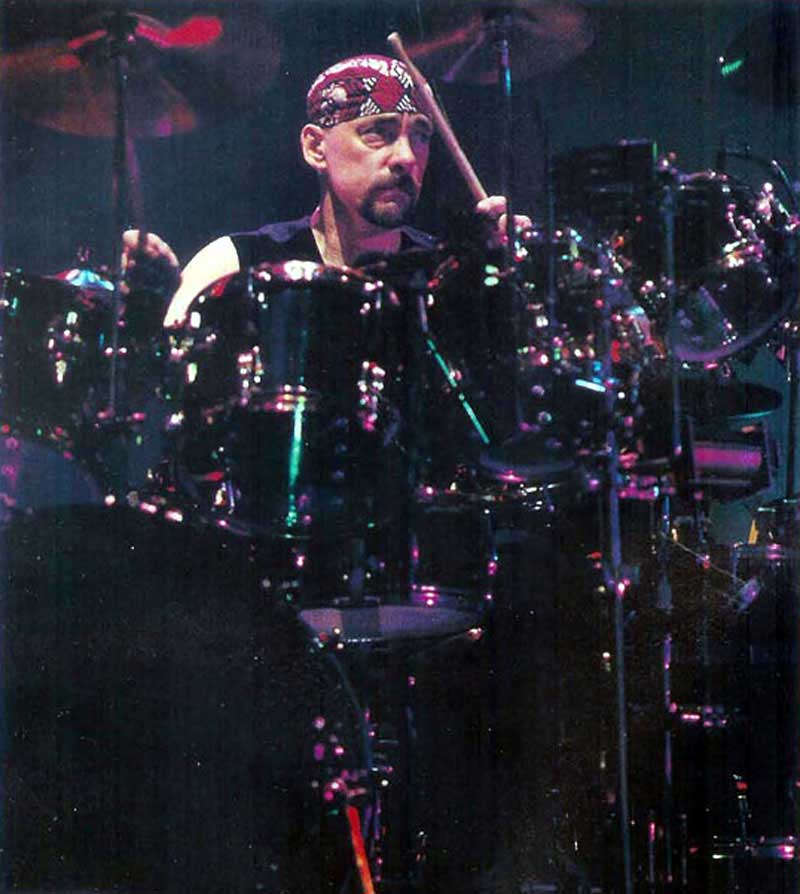

Tech Talk: Neil Peart

By Anne Leighton, Hit Parader, November 1994, transcribed by pwrwindows

Go to a Rush concert and you'll hear great music. Listen to Geddy Lee sing and play bass, Alex Lifeson jam on his guitar, and Neil Peart make his drums talk, scream, cheer, rumble and roar. Nothing in rock and roll is like a Rush show - they don't fit grunge, death metal or "hair band" trends. Rush is their own entity. Almost every drummer in rock thinks Peart is the greatest player, with his fast feet pounding drumrolls and his arms pounding his drumsticks all over the kit. Folks even worship him, which makes him feel ill-at-ease. Peart says "I never wanted to be famous, I wanted to be good. I wanted to be a drummer, not a personality, not an entertainer. I've always had a total problem with fame; it's a destructive thing on both sides." In addition to talking about being an "anti-hero" he called to chat about songwriting and drumming - Neil Peart's craft.

As a writer, you've become a people-watcher. Do you take that further and try to imagine what their entire lives may be like?

I do that with audiences even when I'm on stage, not that I have that much leisure time. But there are little flashes of seconds that go by. The concentration is on 10 and then on 9, back to 10, back to 9. I can't resist imagining their lives and what they were doing the day before they came to that concert what kind of home they go back to. And who can resist flying over a city and looking down and seeing all those apartment windows and seeing those people's lives, every one of them being a novel? That kind of imagination is irresistible to me. Looking at an audience, you're looking at them for two hours and can't help it but reflect on their characters, their lives, their aspirations, all of them.

Can you actually see individuals from the stage?

Yeah, that's one reason why arenas are as big a venue as we're comfortable in. We were - for a long time - an opening act. When we first started headlining it was small theaters which are more intimate because you're dealing with two or three thousand people. They had to kick us into arenas at the point our audience got large enough and we didn't have a choice - we had to play bigger venues. But at least in the arena, when we put the lights on in the audience, I can still see every little circle of light - each little face, even if it's just a circle of light way in the distance - in the nose bleed seats. A couple of times we tried stadium shows, we hated it and felt so alienated from the audience. In fact we didn't even feel like we were playing to an audience. We felt like we were just playing to the staff. We tried it twice and really hated it. So from now on we stick to arenas because it's a comfortable environment to us and we do really feel like we can play to an audience at least in that capacity.

Do you think artists, musicians, folks in the limelight have any kind of responsibility to behave themselves?

Honestly, no. I believe what Humphrey Bogart said, that the only thing you owe the public is a good performance. But that's more than enough! Role models, to me, aren't heroes. Someone who does a good job is a role model, whether they're a basketball player, a drummer, an actor, or a politician. I don't think they're responsible for being super-human. I object to what we expect of our politicians, because it's a hypocritical level of morality that none of us expects from each other or our friends. It's destructive to look for that. I think if you put yourself out there as a performer or an athlete or a politician, you're responsible for doing that job really well. Beyond that, I don't think any other responsibilities fall on you. When you're growing up, you just need someone who's setting a good example on nice ways to behave. As a drummer, my first drum teacher set a great example. He wasn't a hero, and even that great of a drummer, but got me started so that I'll be forever grateful to him. And there's my grandmother, or the next-door neighbor who bandaged my arm when it was all cut up. There are people like that who set a great example of how to behave in the world - they're the people that you really need. You don't need a hero. What about all the people who, up until a year ago, idolized Michael Jackson? What are those people thinking now? Are they feeling betrayed, are they thinking they're stupid, or are they thinking that he's a big phony? In essence, everybody was wrong; they were wrong to idolize him, and he was wrong to let himself become an idol. It becomes an exercise in denial - they deny that he was like that, they deny that Elvis was a drug freak. Why don't they just pick somebody in the neighborhood who's a nice person and say, "I wanna be more like that"?

When you were younger, did you have famous drummer role-models?

Gene Krupa was an early inspiration for me, and certainly Keith Moon was. But then there's...so many...like every drummer I've heard. All the drummers from the late '60s and '70s, I learned from them all. And, again, that's why I like the role-model idea, because that's what they were to me. And some of them changed along the way, too. While Keith Moon was a drummer I really admired, he wasn't a role-model for me because I soon discovered that I didn't like that style of drumming. I liked to listen to it, but when I got into bands that played songs by the Who, I really didn't like it. It was an important lesson to me, that what you think looks good and sounds good might not be for you. I also learned the lesson about quality, that there's a lot of music that I could like might not be good, and there could be a lot of music that's good that I might not like, which is something that people never learn, unless they care about music enough to get to that point. But you'll talk to people, and they'll say, "Oh, that guy's great!" And you ask them why, and they say, '''Cause I like 'em'" Oh, okay, that enough of a reason. It comes down to taste and quality being the same to them. Taste and quality are not the same, and you should know the difference. I can read a book, for instance, and say, "Oh, that was really enjoyable. It wasn't really a great piece of work, but it was enjoyable." Or you can read another book, like James Joyce's Ulysses and say, "Well, that was an amazing piece of work, but it didn't exactly keep me turning the pages all the way through."

Lee Hayes, who cowrote If I Had A Hammer, once said he likes a song that's good and commercial.

That's the idea, of course, but who cares about a hit? That's not a measure of anything. I think it's a false contradiction to worry about that. We make a record and hope that it's successful. We write our songs, and try to communicate something in them. To me, this is a grey area of morality - as far as I'm concerned, it's immoral to be worried about the market. We'd never say, "I like this, but it's not commercial enough, so we'd better change it." We would never utter those words. We just try to make it as good as we can to our taste, and then hope. Those are separate values. You don't worry about a hit, you don't worry about writing a commercial song. You try to write something that you think is really good and then, because you're a human being and other people are human beings too, you hope that they'll respond to the same thing.

Isn't there a craft to your songs, though? Your songs have good hooks.

"Hooks" is not in our vocabulary. I don't mean that in an insulting way, I just know that's how the industry likes to conduct itself, and the language they use. We do try to get accessibility into our music, where we try to say what we want to say clearly enough that other people can receive it. Sometimes it doesn't happen; sometimes the music remains opaque. We don't let our manager call our records "product," we don't let him call cities "markets". Terminology has nothing to do with what we do. It's the music business, but it's not the music. We draw a very firm line between those two things, and keep them very separate. Not everybody has to share that morality, but it's mine and always has been since day one. As a young drummer, I decided I never wanted to play music that I didn't like. And if somebody offered me a job playing in a polka band or a country band I'd say, "No thanks, I'd rather do real work." Three times in my life, I've taken a day job so that I could afford to play the music I liked. That, to me, was a point of honor, but for other young musicians it isn't. They would take the job in the polka band or the country band gladly, because their point of honor is to make a living playing music. It depends on how strong your will is, how stubborn you are, of course, and what your idea of morality is. To me, it's prostitution if you're willing to sell yourself. But that's my morality, it doesn't have to be everybody's. And not that there's anything wrong with prostitution, either. If you wanna sell it, sell it.

The kid that joins the polka band could think he's learning polka music.

That's not what they're thinking. They're thinking, "I could make some money from this." Everything you have to learn as a drummer in a polka band, you could in an afternoon. It's like the old joke about country music, "There are only two country songs - the slow one and the fast one." From a drummer's point, that's how it is.

Aren't some of your influences where the drumming is like polka music?

Absolutely. I love reggae music, but I would never want to be a reggae drummer because it would drive me crazy. I'd be too bored and restless by that amount of repetition. But I'm perfectly happy to listen to it. It's music that's made for its own sake. Again, it's the sincerity factor; I can tell right away if something's for real. That holds just as true for country music or for reggae, or for any style. In country music, if I hear Hank Williams or Patsy Cline, I know that's for real. So much of it is just fakery, like so much pop music. They're just trying to fool you. A theme I use a lot in songs is that you trade your innocence for experience. It's a process of disillusionment, because innocence is illusion. When I was young, I thought that everybody was making the music that they liked, and every song that I heard on the radio was the best that person could do and what they most wanted to do in the world. And what a disillusionment it was for me to find out that wasn't so, that these people were just making music that they thought would sell. It sounds so naïve, but it was a shock to me. I couldn't imagine that the world worked that way. I thought that everybody did what they wanted to do and made a living from it. It was sad for me to realize that all these people were just selling themselves.