A Rebel And A Drummer

By Scott Bullock, Liberty, September 1997, transcribed by pwrwindows

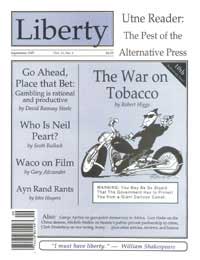

Rush's outspoken individualist drummer talks to Liberty's interviewer about Ayn Rand, his left-wing critics, and the pleasures of not selling out.

Mention that you like Rush to a libertarian or conservative between the ages of 25 and 40, and you might be surprised at the response. Rather than immediately assume you are talking about a tubby right-wing radio commentator, the person will likely think you mean a hard rock power trio from Canada whose songs have vigorously defended individualism and technology for over 20 years.

With no Top-40 or MTV exposure, Rush - guitarist Alex Lifeson, bass player and vocalist Geddy Lee, and drummer Neil Peart - has nevertheless built up an enormous fan base. Its last 16 albums have gone gold or platinum, and the group is one of the most successful and enduring live acts. Rush has a strong allegiance amoung young people tired of the nearly monolithic leftward slant of rock groups. Even a cursory listen to Rush will explain its attraction. As Bill Banasiewicz said in Visions, his biography of Rush, the main interest in the group throughout its career, in addition to making great music, has been in promoting human freedom.

The band released its first album in 1974, chock-full of Led Zeppelin-like guitar riffing, vocal wailing, and pedestrian lyrics. Things got much better by the second album with the addition of drummer Neil Peart. Not only did Peart bring an exciting rhythmic influence to the band, he also became the groups lyricist.

Peart's lyrics were a surprising change of pace, and unique in the annals of rock. At the time most rock lyrics fit into one of three categories: collectivist, left-wing political songs, maudlin singer-songwriter fare, or macabre heavymetal posing. While some of Peart's musings resembled the science fiction-fueled sagas popularized by Yes, Genesis, and other progressive rock groups, Peart's main inspiration was novelist and philosppher Ayn Rand. Indeed, Rush's epic 1976 album, 2112, was inspired by Rand's novel Anthem, a dystopian tale of one man's struggle to revive individualism in a world so collectivist that even the word "I" is prohibited. In the liner notes to the album, Peart sets forth his appreciation for "the genius of Ayn Rand." Peart actually signalled his interest in Rand in 1975's Fly by Night. In that album's "Anthem", Peart writes:

I know they always told you

Selfishness was wrong

But is was for me, not you

I came to write this song.

Rand's influence and philosophy is evident in numerous other Rush songs, including many that have become FM rock staples. Peart's lyrics for "Free Will" neatly sums up the victim mentality of many alternative rock bands (and fans):

There are those who think that

They've been dealt a losing hand...

All pre-ordained

A prisoner in chains

A victim of venomous fate.

Here Peart could have been writing about Billy Corgan of Smashing Pumpkins, who screams "Despite all my rage/I am still just a rat in a cage." But the Rush song rejects this sense of helplessness, insisting that

You can choose a ready guide

In some celestial voice

If you choose not to decide

You still have made a choice

You can choose from phantom fears

And kindness that can kill

I will choose a path that's clear

I will choose free will.

(from Permanent Waves [1980])

In the early 1980s (and even today on album-orientated rock stations), it was hard to escape Rush's best known song, "Tom Sawyer," from 1981's Moving Pictures album. Transforming Twain's young individualist into a "modern-day warrior," the song celebrates maintaining one's independence and inquisitive spirit in an increasingly collectivist world. The song contains perhaps the most Randian nugget in all Rush songs: "His mind is not for rent/To any god or government."

Rush's response to their increasing fame was the majestic "Limelight," also from Moving Pictures. Rather than whine about how rough it is being a rock star, the song takes a clear-headed approach to dealing with the pressures and temptations of stardom. While admitting that "living on a lighted stage approaches the unreal," one must nevertheless put aside alienation and all of the other bogus complaints of rock stars, and "get on with the fascination" of making music. (If only Kurt Cobain had listened.) Driving home the point, the song features a blazing guitar riff and an electrifying solo by Alex Lifeson.

All these songs represent the band's most successful period, 1980 to 1984, when they transformed their style from sometimes meandering progressive rock suites to catchier, more tightly crafted songs. Nowhere is this new approach more evident than in the first song from Permanent Waves, "The Spirit of Radio," which was also literally the first song released in the 1980s, on January 1, 1980. Hearing it in the car, amidst late '70s disco dreck, was a welcome shock, and instantly made fans of many who had overlooked the less radio-friendly Rush songs of the '70s. The song has an insistent, muscular sound that fairly leaps from a car stereo and is itself a paean to radio, and to the sheer exhileration of driving a car with a great song coming over the airwaves.

The song represents another consistent theme of Rush - an appreciation and defense of science and technology. While many rock songs bemoan progress and technological advancement, Rush uniquely embraces science, space exploration (most noticably in "Countdown," from Signals), and, on the band's latest album (albeit with some reservations), the Internet and global communication.

"The Spirit of Radio" also represents, however, a certain ambivalence in Peart's philosophy. Although his lyrics almost always affirm individualism, several reveal a degree of suspicion about a fundamental tenet of Rand's philosophy of "Objectivism" - its belief in the morality of commerce. "The Spirit of Radio" glorifies the technology of radio, but it also rails against the corruption of this bright medium by, of all people, "salesmen!" (sung in one of Geddy Lee's patented shrieks). In "Natural Science," from the same album, Peart states his belief that ultimately "art as expression/not as market campaigns/will still capture our imaginations."

Peart, a thoughtful, self-educated man, was introduced to Objectivism by reading The Fountainhead while a teenager. When he was 18, Peart moved from Canada to England to pursue a music career; but unlike most of his peers, he never viewed music as a "mercenary endeavor." Music, to Peart, is pure expression, and to play only for a paycheck is "prostitution" and "pretty evil." He worked a day job to support himself, and played only music he loved. It's little wonder that he was so entranced by The Fountainhead. As Peart commented in an interview with me, speaking from his home in Toronto, Howard Roark, the book's hero, affirms the principles of integrity, individualism, and self-reliance by which Peart was already seeking to fashion his own life.

Howard Roark stood as a role model for me - as exactly the way I already was living. Even at that tender age [18] I already felt that. And it was intuitive or instinctive or inbred stubbornness or whatever; but I had already made those choices and suffered for them.

Shortly after Peart joined Rush, the group faced a crisis. Rush's first three records had sold fairly well, but the record company wanted more and pressured the group to change its style. Consultants were brought in, and Rush was on the verge of "selling out" to make its music more marketable. After much debate and tension with the band, and between the record company and Rush's management, the group members decided to stick to their artistic visions and reject the advice of their would-be handlers. The result was 2112, a very successful album that both increased Rush's reputation and record sales, and vindicated Peart's artistic vision. So it isn't surprising that Peart expresses some hostility toward salesmen, marketers, or anyone else who would undermine artistic integrity.

The dilemma faced by Rush in the mid-1970s reflects a certain tension in Rand's philosophy - between her insistence on integrity and individualism on the one hand, and the demands of the marketplace on the other. After all, businesses are in a certain sense slaves to the preferences and desires of others (a fact often overlooked by those on the left). If the comsumer does not like its products, a business fails, no matter how principled the capitalist or excellent his offerings.

Of course, Rand never claimed that making money (or selling records) should be the ultimate aim of an entrepreneur (although certainly he is entitled to the money he makes). Rather, a businessperson, artist, scientist, or musician should realize his own dreams and ambitions by adhering to the highest standard possible. Hopefully, others will appreciate quality and be willing to pay for it. If not, then the individual still keeps his integrity. And Peart doesn't attack capitalism so much as he criticizes anyone, inside or outside the business world, who would try to stop an individual from achieving his vision.

"Subdivisions" (1982) also seems to attack one of the crowning achievements of modern capitalism, the suburbs. Long a target of leftist culture critics, suburbs are generally defended by free marketeers as a place where the working class can gain a modicum of comfort and independece unknown in pre-capitalist or socialist societies. Peart, however, sees the 'burbs quite differently:

Sprawling on the fringes of the city

In geometric order

An insulated border

In between the bright lights

And the far unlight unknown

Growing up it all seems so one-sided

Opinions all provided

The future pre-decided

Detatched and subdivided

In the mass production zone.

Nowhere is the dreamer

Or the misfit so alone.

Subdivisions -

In the highschool halls

In the shopping malls

Conform or be cast out...

Any escape might help to smooth

The unattractive truth

But the suburbs have no charms to soothe

The restless dreams of youth.

(from Signals)

To Peart, the suburbs can crush individuality. But is this a repudiation of Objectivism? Most Objectivists and libertarians, and even some conservatists, share Peart's thoughtful skepticism toward mass culture. We may defend suburbs, strip malls, and a Boston Market on every block, but we truly glorify the upstart entrepreneur, the non-conforming artist, and others who challenge conventional wisdom and powerful institutions (many of which are dominated today by the left).

Furthermore, though he loathes the suburbs, Peart writes tributes to cities:

The buildings are lost

In their limitless rise

My feet catch the pulse and the purposeful stride

I feel the sense of possibilities

I feel the wrench of hard realities

The focus is sharp in the city.

("The Camera Eye" from Moving Pictures [1981])

Rand would probably not have objected to Peart's contrast between subdivisions and cities. She lived in and glorified Manhattan, not Westchester County.

For long-time observers of Rush, it is clear that Peart has drifted from his more obvious attachments to Objectivism. The more overtly Randian references in Peart's lyrics have dwindled. Power Windows (1985) even contains a song called "Mystic Rhythms," in which Peart takes an almost worshipful, animistic view of nature. On Rush's latest album, he seems to attack the West for supposedly causing Third World poverty:

Half the world cares

While half the world is wasting the day

Half the world shares

While half the world is stealing away.

("Half the World," from Test for Echo [1996])

But Peart says that he has few problems with Rand's philosophy, citing only two specific areas of disagreement. Contrary to Rand's rejection of any form of government welfare, Peart supports a safety net for those in need. Although he would prefer that welfare be funded voluntarily, he is not convinced that private charity alone could support the truly needy. Also, Peart was turned off by Rand's attacks on hippies and Woodstock:

I always loved machines, and I always loved the workings of mankind in making things. I stayed up all night to watch the Apollo moon landing, and at the same time I was just as excited by Woodstock. There is in fact no division there. In both cases you're talking about the things that people make and do. So I didn't see any division, but of course Rand did, in seeing us all as the unwashed Bohemian hordes.

Although Peart is now inclined to write off Rand's hostility toward the Woodstock kids as a "generational thing," it was her essay on Woodstock and rock music which forced him to realize that he did not agree with Rand on every issue.

That was when I started to not become a Randroid, and started to part from being a true believer. I realized that there were certain elements of her thinking and work that were affirming for me, and others that weren't. That's an important thing for any young idealist to discover - that you are still your own person.

Over the years, Peart has made fewer direct references to Rand, and he admits that one cause of the decline has been the intense hostility such sentiments have evoked among rock critics, especially in Britian:

There was a remarkable backlash, especially from the English press - this being the late seventies, when collectivism was still in style, especially among journalists. They were calling us "junior fascists" and "Hitler lovers." It was a total shock to me.

Flip through any Rush review from the '70s and early '80s, and you're likely to find a reference to the supposedly fascist overtones in Rush lyrics - invariably in reaction to Peart's admiration for Rand. Peart says he was "shocked, stunned, and wounded" that people could equate adherence to individualism, self-reliance, and liberty with fascism or dictatorship. This savage reaction awakened Peart to a "polarity" between Rand's philosophy and that of critics.

For me, religion is life, and nothing else is worth living or dying for - or killing other people for. But a large part of the world is convinced otherwise, so you tend to just allude to it in writing, but shut up about it when you're in an intolerant group. You know, the Salman Rushdie lesson.

Convinced that he should stop sending up "flares" by directly referencing Rand, Peart worked to incorporate her ideas in a more subtle manner. The Randian elements in such songs as "Tom Sawyer," "Free Will," and the more recent "Mission," (from 1987's Hold Your Fire) are far more effective than the heavy-handed style of "Anthem" and 2112. This movement away from hard-core Randianism paralleled Peart's rejection of involvement in the organized movement:

In the late seventies I subscribed to the Objectivist Forum for awhile. And it could be such a beautiful thing, it could be like a breath of fresh air coming in the mailbox. But it became petty and divisive and also factionalized....I tend to stay away from it [now]. It's in the nature of the individualist ethos that you don't want to be co-opted.[Also], the ones most devoted to the cause are the ones with least of a life. A friend of mine who was involved in the Ayn Rand estate and the initial institutes and so on noticed that all of the coteries surrounding her didn't do anything....

The whole philosophy is about doing things... with an eye towards excellence and beauty. And that was the one thing that was lacking in any of the coteries surrounding her. So that's another reason people stay away from [the official Objectivist movement], saying, "Well, I have a life and I'm living the philosophy - so why do I want to stop and talk about it with other people who aren't doing it?"

Peart acknowledges that other thinkers besides Rand have influenced his philosophy. Jungian psychology, for instance, provides themes for a number of songs, and Peart also cites John Dos Passos as an influence on his thinking. Still, the Objectivist influences persist. Encapsulating the Objective cultural critique, Peart remarks that in too much of popular culture today, only the "poor and dumb" are glorified, never the "rich and smart." And his "Heresy" (1991) is perhaps the only "fall of communism" song that recognizes the essential link between personal and economic freedom:

All around that dull gray world

From Moscow to Berlin

People storm the barricades

Walls go tumbling in

The counter revolution

At the counter of a store

People smiling through their tears.

(from Roll the Bones)

Politically, Peart describes himself as a "left-wing libertarian," noting that he could never be a conservative due to the right's intolerance and support of censorship. Moreover, the rise of religious fundamentalism in America and throughout the globe "terrifies" him. But he also sees rising intolerance coming from the left, exemplified by a Toronto law "forbidding smoking in any bar, restaurant, coffee shop, doughnut shop, anywhere." Thus, though he believes that economic freedom is generally increasing, Peart also observes that "socially it seems to be the opposite - there is actually more oppression."

Apart from the unique lyrics and world view, another aspect of Rush that makes the group so appealing, especially to hard-core music aficionados, is that all three members are virtuoso musicians. Each one of their albums demonstrates a refinement of their musical skills. The members take music seriously and constantly explore new musical ideas. Neil Peart is one of the most admired percussionists in any genre of music, a sort of drumming ubermensch whose extraordinary technique dazzles and delights musicians and non-musicians alike.

Last year, Rush released its 20th album, Test for Echo, and will tour again this summer to sold-out venues. Whether the band will break up after this tour is discussed passionately among fans over the Internet. Whatever the future of Rush, libertarians and Objectivists can delight in a band whose music they can enjoy without having to ignore or cringe at the lyrics. Some of Peart's lyrics can be strident or contradictory, but most are eloquent and desperately needed defenses of individualism in a collective age:

I'm not giving in

To security under pressure

I'm not missing out

On the promise of adventure

I'm not giving up

On implausible dreams -

Experience to extremes

Experience to extremes.

("The Enemy Within," from Grace Under Pressure)