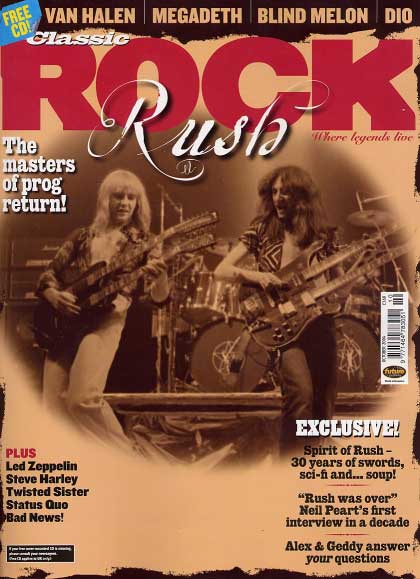

The Masters Of Prog Return!

Classic Rock, October 2004, transcribed by John Patuto

- Closer to Their Art

- Grace Under Pressure

- The Sword & Sorcery Phase

- The Art Rock Years

- The Back-To-Basics Years

Thirty years and counting...Despite nearly imploding, after the terrible events that occurred in drummer Neil Peart's life, the progressive trio from Toronto are back firing on all cylinders and about to make their first appearances in the UK for over 12 years. In celebration, Classic Rock ventures to Nashville to confront Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson with your pertinent Rush questions, and Neil Peart agrees to be put under the interview spotlight for the first time in a decade.

Closer to Their Art

By Philip Wilding

Even after a 30-year career and with more than 20 albums under their belt, Rush are as enthusiastic as ever. With a new CD, 'Feedback', just out and an overdue UK tour about to begin, Classic Rock puts questions from you, our readers, to Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson. I've started so I'll finish: Philip Wilding

Nashville is unseasonably cool, but that doesn't deter Alex Lifeson and Geddy Lee (from) wearing shorts while sound-checking. Each time the band run through the introduction to 'Subdivisions', the Starwood Amphitheater - a natural horseshoe-shaped bowl fitted out with an unnaturally large stage and tiers of red and blue plastic seats - booms deafeningly. It's empty in here. It's a venue designed for around 18,000 people, so band, crew and a handful of guests do little to sponge up the sound as it rises up and out from the stage. A small, blond-haired boy in matching blue shirt and shorts wanders past me wearing a quizzical look and a giant pair of bright red ear protectors that sit unevenly over his ears like two giant ladybirds. He stops and squints up at me, looking for all the world like someone off a Rush album cover from the late 80s. He gives me a solemn wave and a jerk of the head. Geddy asks the band to try 'The Seeker' one more time for luck ...

Later tonight, Rush will play their entire three-hour show in final preparation for their 30th anniversary tour - all 57 dates of it - which begins tomorrow. After weeks in a rehearsal room in Nashville, they're ready to tryout the set list they've finally selected. Their covers album, 'Feedback', which pays tribute to the bands that thrilled the trio in high school (The Who, The Yardbirds, Buffalo Springfield, among others) is finally done and by the time they return home in early autumn Rush will have been across America, briefly visited their native Canada, and played their first European shows in over 12 years.

Backstage, Alex and Geddy slouch on a leather sofa as they flick through the questions Classic Rock readers have sent them. Across the corridor, Neil Peart rattles off a thundering tattoo that sits me up sharply in my seat. Alex and Geddy hardly seem to notice the noise pulsing through the door. "Neil," nods Geddy, holding sheets of A4 gingerly in his hands, "he rehearses to rehearse." Alex grins in agreement, turning over his pages with curious interest.

Why the new 'Feedback' covers album? How did you choose the material?

Chris Tollingron, Canterbury

Geddy Lee: It was short and sweet and it came up quickly. We've always talked about throwing cover songs into our shows for fun, but we've never really followed through on it. Then a friend of mine suggested that if we weren't going to do a [proper, all-new studio] album then maybe this was a good way we could pay tribute to our past.

Alex Lifeson: These are songs we played when we were in basement bands, when we were thirteen or fourteen years old. And there was no pressure, because if in the end we didn't get off on it then we wouldn't do it.

Have you got a favourite Hugh Syme album cover?

Andy Bass, Brighton

GL: I love the packaging he did on 'Different Stages', that's one of my favourites. I'm touting tickets outside; Alex in a straitjacket...I think 'Vapor Trails' is one of his best as well.

AL: 'Signals' was very clever, too. I liked that one.

Be honest, did you shed a tear when you finally put the double-neck guitars away for the last time?

John Dryland, London

AL: Well, sadly, the doubleneck's back - we're playing 'Xanadu' on this tour. I'm shedding a tear because it's back; they're so heavy, they feel like they're seventy-eight pounds, they're awkward, so head-heavy you have to hold it up and squeeze your arm in to keep it in place. To be honest, they're not particularly comfortable to play.

GL: Mine's in the Hall Of Fame in Cleveland in an exhibit of our equipment, and the other one I had was a six-string bass and I gave that to a friend, so I haven't owned one for a while. I don't particularly want to play it again - it's so awkward.

I'm in a band called Tom Sawyer. Do you think Rush tribute bands are a good or bad thing?

Tom Alexander, Carlisle

GL: They're very complimentary. There are times when I'd wanted to hire one to go do this for me.

AL: It's a nice compliment. Everyone starts being a tribute band in one way or another; we had our Led Zeppelin days.

GL: If they can figure those songs out and learn how to play them, then more power to them. In fact there was one band once that used to advertise itself as sounding more like Rush than we did. I liked that. They were the ultimate Rush covers outfit and they sounded more like Rush than Rush; that was their catchphrase.

What did you think when you heard that Dream Theater were including '2112' in their live shows?

Rory Sullivan, Oxford

GL: I didn't know that. Thank you, Dream Theater.

AL: Is that right? Now those boys sure can play.

Is this tour the band's way of saying goodbye?

Darrin Padilla, Qatar

GL: No, we hope there's going to be more studio albums. We're looking forward to doing something next year.

AL: We really got the bug when we were doing these arrangements for 'Feedback', and we both said how nice it would be to start writing together again. So we want to do another record for sure.

How is middle age treating you?

Matthew Goldberg New York

GL: I don't like being age fifty, I don't like the number so I try to avoid it. I work hard at being in shape, but I have a young daughter so that's incentive enough to stay in shape. I don't want her to have an old fogey for a father.

Why does 'Caress Of Steel' usually get overlooked when you're putting together a set list? Do the songs bring back bad memories?

Joseph Brennan, Denver

GL: There's a moment of 'Caress Of Steel' in the live show. It's not my favourite album, it has its moments...It's hard to choose the songs with so many albums, and you have to address what people want with what you feel like playing. It doesn't bring back bad memories of the time or anything; I don't think 'Fountain Of Lamneth' is a very successful concept, but we learned a lot from that. '2112' came out of that, so it was (a) stepping-stone record.

After seeing the Easter Egg (hidden) clips on the 'Rock In Rio' [sic] DVD, how much unreleased video footage of Rush is still in the archive?

David Edwards, South Wales

GL: The last couple of years my brother's been in charge of all our video production stuff, and a lot of the stuff for the live show he's produced too. There's a bunch of unreleased stuff, but I don't know what we'll do with it. We're sneaking a lot of it in to the anniversary show, so we'll see.

If you could go back and re-record one of your albums, which one would it be and why?

Keiron Stancombe, Devon

GL: Some records I'm not terribly happy with the sound of: 'Presto' is a disappointing-sounding record. From a sonic point of view, it could sound a bit bigger. But they're points in time, there's no point going back. I think the material is strong, and now that is also an album cover I love.

If the year was 2112 and you were the Priests of the Temples of Syrinx, what would you ban or prohibit?

Paul Tippett, Berkshire

AL: I would ban rainy days and mean people.

Is there one song by another artist that makes you stop and think: I wish we'd written that?

Jonathan Miller, Birmingham

GL: Oh, tons. Whenever I hear 'Solsibury Hill'...actually, most of Peter Gabriel's songs I wish I'd written them. There are so many.

AL: The McDonald's restaurant theme song; it would have been great to have written that.

Why do always play on a carpet - for luck?

Ian Sewell, Birmingham

AL: It's comfortable, it absorbs the light...it reminds us of when we were young, practising in our parents' basements on the shag-pile carpet.

GL: We have good carpets.

What was the easiest Rush song to write?

John Matthews, Chicago

GL: There are lots of songs that came together quickly. 'In The Mood' was probably the easiest song we wrote; the bad ones are easy to write.

AL: The Pass' came together very quickly and so did 'The Twilight Zone' and 'Vital Signs' too.

GL: There's usually one or two songs that we end up writing just on the spur of the moment in the studio; 'New World Man' was like that. With 'The Pass', because the lyrics are so strong I found the melody came quickly, and Alex and I put the music together around it. Some songs just fall together, drawn out of the lyrics.

Weather aside, after 12 years what are you most looking forward to about touring Europe again?

Joe Davies, Aberdare

GL: I'm just totally happy to play for our fans there again. I feel bad that we've ignored them for twelve years, and I'm glad we can correct that in some way.

AL: It's going to be so much fun to come back; it's so different to North America. And it's going to be great to come back and spend some time touring around, experiencing a few new cities I've never been to, such as Prague and Milan...We can't believe the way tickets have sold, it's amazing.

Thirty years is longer than most marriages. How close did Rush come to hitting the divorce courts?

Duncan Callow, Ashford

AL: It was after the 'Hold Your Fire' tour for me. We'd just got back from Britain and had gone in to mix 'Show Of Hands', and we were exhausted and nobody wanted to talk about any kind of future at that point.

GL: We've had a few rocky spells, but mostly that is driven by exhaustion, it's not anything to do with. When you step back and look and what you're doing and why you're doing it, then you never want to stop. We're really lucky that the three of us still have the same musical vision and the process of doing it is fun. So as long as those two things coincide then I think we'll still hang around.

What was the last CD you bought?

Keith Fields, Denver

GL: The last CD I bought was Jeff Beck's Truth'. I was doing research for the 'Feedback' project.

AL: The Mars Volta album, it's a crazy record. I think I like it. I think it's the kind of record that you have to sit down with and get inside the whole thing.

Rush's passion for soup has been well documented. Any other plans to follow celebrities (eg Paul Newman) and launch your own range?

Neil Lach-Szyrma, St. Albans

GL: This is from the interview we did on the Rio DVD, right? No, we have no plans for that. We could ask Frenchie, our cook, and maybe put him into business. As we get older we're getting sillier, I admit it.

Have you ever been approached about making '2112' in to a film, and have you ever tried the Willy Wonka 'thing' [where the music on '2112' is supposed to synch with the film?]

Piers Leighton, London

GL: Somebody talked about doing a film version, in the eighties, I think, but it never went very far. It's something I think could be done well. And the Willy Wonka thing, I've never done that - if you time the movie to '2112'...things coincide, right? [laughs]

Which of your songs song came closest to not making it on to an album?

Edward Douglas, Aberdeen

GL: The first version of 'Earthshine' sounds nothing like the one on the ['Vapor Trails'] album. We threw all the music away; we thought the lyrics were great and it was the first thing we wrote musically and we liked it for a week and then the doubts crept in. There are usually one or two songs that you're struggling with tooth and nail. 'Tom Sawyer' was one of those songs, and right up until the end it was a struggle. Everything we did on that song was just like pulling teeth. Alex went through a hundred different sounds for the guitar solo. There's always one song that haunts you and drives you crazy.

You're on a desert island - what's your one luxury?

Phil Littlewood, Bath

AL: A big, modern city.

I know it's like asking a parent to name their favourite child, but is there one of your albums that you think defines Rush best?

Darren Hightower, Dallas

GL: I'd like to say 'Moving Pictures', but then I'd have to say '2112' and then I'd have to say 'Power Windows' as well.

AL: Albums define us at that moment, and I don't think we've stopped developing or growing, so that's a tough one, impossible to answer.

Will there be a 30th anniversary box set, and if so will it include rare and unreleased tracks like 'Tough Break' (from the 'Signals' sessions) and older material like 'Margarite' and 'Tale'?

Troy Kennedy; Detroit

GL: I don't know about a box set.

AL: Tough Break' is a song by Jack Secret, he's Geddy's keyboard technician. He wrote a song that Neil and I did a little bit of work on. But they're not actually our songs.

GL: We did have a really old song called 'The Tale', but I don't know about 'Margarite'.

AL: John Rutsey [drummer on debut album] might have written a song called 'Margarite'; I spend all my time trying to forget these things.

How do you feel about your sex-symbol status among your small but fiercely loyal female fan-base? For the record, we don't find Rush any less sexy without the kimonos.

Tiffini Riley; Illinois

GL: Thank you very much. Where can I get in touch with you?

AL: Tiffini, you're an angel.

GL: You know all the right things to say. Some people get off on kimonos, I suppose.

Have drugs ever influenced your work?

Mat Precey, London

GL: Constantly.

AL: Absolutely.

What did you think of Rainbow using a photo of your fans holding a banner, and adapting it for the inside of their 'long live Rock 'N' Roll' album? Did they pay for using it?

Simon Browne, Middlesex

GL: I don't know who did that.

AL: It is a Rush show, it's Portsmouth, Michigan.

GL: You'd better ask Fin [Costello - Classic Rock photographer], it was his shot.

How ticked off are you are not being inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame, really?

Alaister Lyall, Glasgow

GL: My guitar's in there, I'm not! Actually, it's better than me having to carry it around. These things are outside of us, that's how I feel about it.

Where's original Rush guitarist Mitch Bossi?

Ian Morgan, London

GL: He was a rhythm guitar player who was in our band for a short time.

AL: But he was not an original, he was there I guess it would have been late seventy-one. He was only in the band for about five months, we were just kids. He was good-looking and had good hair, but he wasn't a very good guitar player and he wasn't that interested in the musical side of being in the band. But, yeah, good hair, that's important.

GL: And John Rutsey? He just wasn't up for it, psychologically. He just didn't have the stuff to go on the road. When we got our first deal and the songs started breaking he just...it wasn't a life he wanted to pursue so he just bowed out.

We've had a large fridge, three tumble dryers...which domestic appliance will you have on stage next?

Jon Dahms, Ramsgate

GL: You'll see when we get to Europe.

What do you think of each other's solo albums?

Jane Partridge, Kent

GL: I think 'Victor' is a really interesting record. Really highly creative, very dense. Neil's done good versions of those big-band numbers on his. I don't listen to it a lot, it's a drummer thing.

AL: 'My Favorite Headache', I thought it was great. It sounded great, the songs are really good.

Like Zeppelin, you've used the author Tolkein for inspiration. What did you make of Peter Jackson's Lord Of The Rings adaptations?

Tom Penrose, Scarborough

GL: Oh, I loved them. The second's my favourite.

AL: Amazing, and they were true to the book. I can't wait to see them all in sequence. Peter Jackson did an incredible job.

How much money would it take to get Rush to record another concept album?

Anthony / Rodarte, Arizona

GL: Ten million dollars! But I am thinking in nineteen-seventy terms. It's not impossible; it could happen.

Is it true that Alex was involved in a film during the 70s, called Come On Children, and if so is it available anywhere?

Carl Moran, Dublin

AL: I was involved in that. It was ten kids living on a farm together for ten weeks and the interaction between them, and the cameras were always on, like reality TV before reality TV. Alan King was the filmmaker and he had made a few films like that; A Married Couple was one. I auditioned for it and there were about three hundred kids who went up for it.

It didn't turn out the way Alan envisioned it would. We weren't very interesting so nothing really happened with it. It kind off flopped as an idea. It shows up on TV occasionally; I've seen it, it was on a few months ago. I was going through the channels, and there I was and it was really shocking. It was nineteen-seventy. I was seventeen at the time.

Does someone really burp at the end of 'The Camera Eye', or is it my speakers?

Mark Irwin, Carlsbad

GL: There is a noise there, but not a burp.

AL: A fart maybe, but we're not rude enough to burp.

As 'Hemispheres' and 'A Farewell to Kings' were recorded at Rockfield Studios, I've bet a friend that the birdsong on 'The Trees' and 'Xanadu' comes from Welsh birds. Do I win?

Paul Lewis, Porth

GL: It is a Welsh bird and he does win the bet.

Can Neil sing, or play anything apart from drums?

Jack Smith, Portsmouth

GL: He cannot sing.

AL: And he can't play anything at all, including games and cards.

Do you ever watch Neil's drum solo from the side of the stage, and do your jaws drop?

Rick Shadle, Phoenix

GL: Every night.

AL: Our jaws still drop.

GL: He's disgusting.

Did Rush ever throw a TV out of a hotel window or trash a tour bus?

Robin Dewson, Bedford

GL: We've partied hard, yes we have; we've had our moments.

AL: We never threw a TV out of the window and we never trashed a tour bus because that was our home. But the odd hotel room, yes. We've rearranged furniture.

GL: Usually when we were too drunk and we'd been away too long. When you're away too long and you're living in this unreal world and you have frustrations and they come out.

AL: Or you're simply in a mischievous mood.

Gene Simmons used to refer to you as the 'junior Led Zeppelin'. Do you take that as a compliment?

Denise McBride, Illinois

GL: We think quite a lot of Led Zeppelin, it's true.

AL: Geddy has been on holiday and met Robert Plant.

GL: We had connecting rooms at this hotel, and he was leaving his room as I was entering mine and we looked at each other. Then about an hour later we were in the restaurant and we started talking. He's a charming guy. We got along great. And then he came to Toronto and gave me a call and me and Alex went down to see him and Jimmy Page play. He's a good guy.

AL: And we met Jimmy Page, and I was so excited. It was the summer of ninety-eight. They sounded so good and Page played so well. We were in the dressing room talking to them and they were so gracious. We were talking to them right up until they went on stage. With us no one's allowed in the dressing room half an hour before the show, with them we were chatting, and the crew came to get them and we walked with them toward the stage. We stood by the monitor board on Jimmy's side, it was a real treat.

Why do you think the 'Starman' logo has endured so much, even after you stopped using it?

Craig Okes, Nimitz

GL: Good branding, like the Nike 'swoosh? It must be his bum; people like the guy's bum.

AL: And the fist, the whole bum and fist thing!

Before you were headliners, who were your favourite band to open for?

Kevin Watkins, Salisbury

GL: Kiss were always great to play with. They were an example of how to work hard and put on a good show, they played all the time, they taught us how to entertain an audience. They had a work ethic.

AL: Rory Gallagher was another. He treated us really well. Blue Oyster Cult, Bob Seger...they were great. We played with everyone.

Does Alex really eat a lot of cheese?

Joe and Anita, El Paso

AL: This is Geddy's fault!

GL: We had Rush facts on the website and they were all bullshit. That was one of them. No, not as much as people think.

Geddy, how far are the Bluejays (baseball team) going to go this year?

Paul Jones, Chepstow

GL: Not very far. Their new uniforms look awful, too. In all fairness, they've always had bad uniforms. But I believe in them.

And finally ...

When you argue, who usually wins?

Mark Foster, York

AL: He does.

GL: That's not true.

AL: We never argue, we discuss.

Grace Under Pressure

By Philip Wilding

Apart from chatting to a few drum magazines, Neil Peart hasn't done a major interview in a decade. As Rush begin their 30th Anniversary tour, Classic Rock persuades the enigmatic drummer to break his silence. All ears: Philip Wilding.

Neil Peart's dressing room is bordello red. Across the corridor from the one Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson share, Neil's is filled with a black-and-white drum kit that dominates the space. Possibly not to be outdone, Geddy and Alex keep a well-stocked bar in theirs. Neil's smoking; he smokes a lot. He grins a lot, too. This is not the stone-faced drummer lost at the back somewhere behind racks of equipment, sparkling aluminum stands and sets of cymbals grouped around him like satellites around the Earth. That's when he's concentrating, his face set hard against the ever-shifting beams of light making great washes of colour across the stage.

Back here at the Starwood Amphitheater, before Peart practices for over 30 minutes just so that he can go on stage to rehearse a three-hour set (including a drum solo that makes your arms ache just watching it), he's relaxed, excited, up. A few drum magazine interviews aside, he hasn't really spoken to the press since Rush toured their 'Test For Echo' album.

Peart's daughter died in a car accident in the summer of '97, then less than a year later his wife succumbed to cancer and also died. Rush as an entity pulled down the shutters and turned off the light. Time passed. Eventually, Peart moved out to California. And then, in September 2000, he married again. One two-week period aside - in which he played every day - he didn't pick up his drumsticks for four years.

Peart had lost his spirit - that was how Geddy Lee had put it to me when I'd interviewed him and Alex around the time of their then comeback album, 'Vapor Trails'. That album belied the fact; it was ferocious and dazzling, and prompted you to remember why you'd fallen so heavily for Rush the first time around. It's themes hinted at heartache; its imagery aspired to redemption. The tour that followed it, including a string of sold-out stadium shows in South America - the band's first on that continent - proved their vitality, not least to themselves.

I hadn't been sure what to make of Neil Peart. Press cuttings suggested economy and wit; his books, especially the excellent Ghost Rider (which charted his tragedies and the journey he took to come to terms with his loss), a talented, self-effacing voice. Live, however, his deeply furrowed brow and permanently buttoned-up lip put me in mind of a former headmaster who bore a grudge against me, albeit one sporting what looked like a deflated fez. In interview, there are brief moments of introspection, admittedly, but only when Peart is attempting to fully articulate answers to certain questions (none of which he ducks, by the way). Otherwise, it's long ribbons of cigarette smoke and lots of laughter - and no sign of that hat.

The three of you seemed to have a lot of fun making your recently released 'Feedback' covers album.

Oh yeah, you know, the songs that we first learned chords and drum parts to in the first bands we played in that influenced us when we were fourteen or fifteen...how couldn't you? It was great, and so much fun to go in and not to write the songs and not worry about the lyrics and construction. Normally in our cycle of things - album, tour, time off-we should have been making an album right now, but we weren't going to miss our anniversary and not commemorate it in some vital way, so we came up with that. And we recorded them so fast. We were whipping off a couple of songs a day, easily.

How did you go about choosing the live set-list to celebrate Rush's 30th anniversary?

That was big. We started at the beginning, you know. We do 'Finding My Way' at the beginning, we do the 'R30 Overture', songs we wanted to play, but not in their entirety. We always wanted to bring back things like 'Mystic Rhythms', so we just added a wish list. And, of course, we had way too many. 'Closer To The Heart' got retired because we got sick of it, but our other songs are pretty difficult to play, so you don't get sick of them every night. They're not songs you can easily cover, either. There was that British band Catherine Wheel, who did 'Spirit Of Radio', and they did a really good version, and I heard an interview with the guy going: 'The parts we left out were the ones we can't play...' [laughs]

Your personal touring schedule is different to the rest of the band's, isn't it?

I leave straight off the stage and sleep on my own bus in a truck stop or somewhere. Then I load the bikes off in the morning and, if it's a day off, I ride somewhere in the mountains or wherever. Or I get up in the morning and ride into the show and just have a world apart as much as I can. I started doing that around 'Test For Echo'. I used to bicycle before that. I always had a bicycle on the bus with me, and at least then I could get the bus to drop me off and I could get away. But the motorbike is, like, complete freedom.

On the Rush In Rio DVD you all look pretty beat up by the demands of a long tour. How will you cope with the 57 dates you're doing this time?

As long as I can play well, I don't care about injuries. The 'Test For Echo' tour I had an elbow brace on my arm at the end of that, but I can still play well. I don't care if it hurts, as long as I can get in the default position, as it were. It's when you can't play that it gets depressing.

I know that Geddy didn't feel like he was getting to play fully during tours for albums like 'Hold Your Fire'.

With the late eighties there was so much technology available to us that we couldn't resist. We have this rule that we have to do everything ourselves; there's no tapes. If I can hit a trigger for a keyboard sound, I will, and Alex and Geddy were dancing all over to cover sounds. That's something now that when we put a set together we're very conscious of. Geddy's like: 'I don't want to be up on the keyboards all the time.' So we separate them out. And that's the joy of our older material and the 'Feedback' stuff, we just play.

On a happier touring note, you got to play '2112' in its entirety for the first time on the 'Test For Echo' tour.

When it came out in seventy-six we were still supporting or doing an hour-long headline set, so we did an abridged version even at the very beginning. And even when we started headlining small theatres and such we still kept it abridged. So by 'Test ...' we thought it was time. And playing it you do find yourself grinning at the past in a way, being in that young man's headspace. You tend to be harsher on your old material than you need to be, and then it's: that's not so bad at all. And for some of them you go, wow, that's good. So they make it back into the set.

After the disappointing reaction to the 'Caress Of Steel' album, you almost didn't get to make '2112'.

'Caress ...' didn't actually do any worse than the albums before it, they all did about a hundred thousand copies in the US. But if our record company hadn't been in such turmoil, I don't think we would have kept our recording contract with three records only selling that many copies. That tour, too, was so stagnant. We called it the 'Down The Tubes Tour', we joked about it among ourselves. By the end of that year we were unable to pay our crew's salaries - or our own.Things were dire, and we were getting a lot of pressure because that was in the summer of seventy-five, and by the end of that year we were in the proverbial dire straits. Polygram had written us off before '2112' had come - we'd seen their financial predictions for seventy-six and we weren't even on it! And then it was all, they don't want a concept album...It became a do or die situation. Fortunately, things just turned around slowly; we were getting better gigs and the records started selling better. We became respectable or something in the industry and then we never got intrusion or leverage from the record company. It was the turning point, true justice!

Do you think 'Caress...' deserved the criticism?

It was weird. We loved it so much when we made it. We were flushed with the excitement - it was our second album together as the three of us - and we knew we were going all over the shop stylistically. Then when it didn't do well we were kind of stung about it for a little while. No, I don't think it really stands up. It is all over the shop, and it is experimental, and it's only real virtue is its sincerity, but at least that's something. We see our bridges, though; we wouldn't have made '2112' if we hadn't made that.I can trace the roots of all our material from our previous experiments. Sometimes the experiment didn't work but the lesson is learned and it becomes a template for the future. It's about nineteen-eighty that I really start to like our music like a fan. Before that there's stuff I like in an affectionate way, because we were brave, but as far as achievement I really think we started to bring it together a bit with 'Permanent Waves' ..., but particularly 'Moving Pictures' and from then on.

'Caress...' was also your first album that had cover art designed by Hugh Syme.

He was playing for the Ian Thomas Band when I met him, and they had the same management company as us. They showed me some artwork he'd done for Ian Thomas and I really liked it. I had collaborated on [preceding album] 'Fly By Night' with the art director at Mercury Records, so I was kind of the spokesperson for our graphic arts department. I still am. Hugh and I struck up such an artistic collaboration that he and I can be on the phone and bounce ideas off each other, and know how it's going to look before it's done. He does my book covers, my videos, the instructional DVD...he's my graphics art guy."

But you were foiled in your attempt to get cartoon cat Snagglepuss on the cover of 'Exit Stage Left'.

We only wanted the tail for 'Exit...'. We wanted to have the rest of the cover and just his tail exiting stage left. But even the tail was beyond the pale, moneywise. We went through a similar thing for Rio when we wanted to use 'The Girl From Ipanema', and they wanted something like forty thousand dollars just to use it. And our publishing guys said: 'Do you want to reconsider and use something else?' And we didn't, because it's a highlight of the show, Alex introduces us and I play a little and then Geddy goes into '...Ipanema', so we had to have it whatever it cost. There are amazing things like that that you run in to all the time.

Going back to the 70s, you've described that decade as 'a dark tunnel', while one of the tours you did in that period became the Drive Until You Die tour. Were things really that bad?

We were playing so much, we were doing nine or ten one-nighters in a row, and we were driving ourselves, don't forget - we were doing three-hundred-mile shifts each across Texas. It was play, drive, play drive. And if you did get a day off there was no recreation about it, you would just lie in a dark room and be stunned, watching cartoons because you were so drained. It was soul-destroying. It takes so much out of you. It was an important turning point, because we hadn't learned to say no yet; we were these kids from the suburbs. So that's where we were caught in the mid-seventies. Then we'd go off the road and straight into the studio. We did four albums in the first two years and then one every year afterward, and we were playing so much. Then, we'd go in with a few acoustic guitars, some words sketched out, and we'd blitz, just work and as hard and as long as we could. We'll never do that again. We had to learn that we can only do so much. It was impossible to hold any kind of relationship together at the time, let alone between us three.

You said that making 'Hemispheres' has left you with a few scars, some which are still visible. What did you mean by that?

We were just coming out of a long period of work, and I think we'd ended our tour in Britain. We went straight off to Wales to record an album with nothing written and just worked ourselves into the ground. The job gets done and doesn't suffer for it, but you do. Whatever it takes, it was always the same with us, all those years. The shows didn't suffer, they got better; we built our legend as a live band - and what a great legend to have. But that record took so much out of us that stress suddenly became a factor and we realised that we had to make a decision about how we were going to work in the future. I think it was a hard lesson learned.I remember that at the end of 'Hemispheres' we said we were never making a record that way again, that part was over. 'Permanent Waves' was a step, we were stepping out of the longer formats to a certain degree, especially with 'Spirit Of Radio' and 'Freewill'; we were learning to be more concise. A lot of lessons were learned at that time. We stepped back from it.

Tell me a little bit about Canadian author Lesley Choice, who helped you get your first book published.

I loved his writing, and I wrote to him, just a fan letter, and he wrote back and said: 'You write well. Ever thought about writing a book?' And I was like: 'Who, me?' I'd written about eight books by then, but had just published fifty copies for friends. That was a luxury I had that I never had in music; I didn't have to grow up in public. I would write things with way too many adjectives, stream-of-consciousness stuff, and it was okay to do that. By the time I'd got to publishing The Masked Rider I'd written six to eight books by then and put them aside. And everything fits in travel writing - it's like a backpack - and that's why I gravitated to it.

And you wrote Ghost Rider during the sessions for 'Vapor Trails'?

I was writing it all the way through. We were in the studio for a year, working quite leisurely at the songwriting, and while I was working on the lyrics I'd always try and write a page a day. By the time we were mixing I was in the revisions of Ghost Rider. So I was in the studio lounge, the guys are back and forth, there's a mixing desk right there behind the window, the TV's on, people are in and out, and I'm trying to revise. It made me realise that it started back in the seventies - my constantly reading to escape a crowded dressing room. I learned to focus that way. Now I have my own little room and my own bus I have privacy, but I couldn't get it then and the only way to get some was to hide behind something, and the book became that.

You've always said that your lyrics were informed by prose more than by poetry.

I always read prose, though I have gone back now and learned to appreciate poetry a bit more. But they [lyrics] are always written as song lyrics, not as precious poetry. And my stylistic influences were always prose writers who created moods, and those were the people I read. I've developed...you learn the skills, as you do in music. It's a craft. And a very hard one to put in simple words when you have a complex reason to life or a feeling within yourself. The more skill you have at that, the more satisfying it becomes. A song is...what, a hundred words? That's very little to get right what you want. I love bringing the words to Geddy and Alex. I sense their belief even if they want to change a part here or there, because I know they're going to like it. And that excites me.

Talking of people you admire, you've praised TS Eliot's ability to 'flood the image'

It made me realise you could enjoy something even if you didn't exactly understand it. At first it can be intimidating; it was like when I was a teenager and I saw my first Fellini movie. I was like: 'What?!' But those images stayed with me, and there would always be a line in TS Eliot that would come home to you and you would resonate with it. As a lyric writer, you're trying to trigger an emotional response, and because your words are being sung as well that gives you so much more ammunition. When I first hear a song being sung I can tell what resonates with Geddy and works in his heart. It's music, after all, not science.

And you avoid overtly confessional lyrics?

I like to find the universal aspect of a song. A lot of the songs on 'Vapor Trails' are an example of that. They're obviously very personal. but I try to find a way to transcend them. This is what memories are like for everybody - those vapor trails in the sky. It's not just me, they fade. The nature of memory I explored in a few of those songs - even 'Ghost Rider' [the song] is about my travels - but I tried to find universal emotional touchstones that other people could discover in their lives. Maybe people will find their own resonance in a song. I like to weave imagery that has a basis in me, so that it's heartfelt, but that is also obscure enough so the listener can find something within it for them. It's like a wind chime; the wind blows through it and makes it sing.

The lyrics to one of your songs, 'Limelight', seem a pretty straightforward distillation of the problems of fame.

We were dealing with that at the time, especially me as I'm kind of shy. That song was trying to deal with those themes and express them in some way. I realise now that it's inexpressible. When someone comes up to me and goes: 'Neil!' And you don't know them...If anyone in normal life gets recognised by a stranger then it's just weird. I never set out to be famous, I set out to be good.

What can you remember of the first show in Hartford, Connecticut, when the band kicked off on the 'Vapor Trails' tour? It must have been a massive step.

It was so emotional for the three of us, because they [Geddy and Alex] had been so strong for me and so supportive through my troubles. We hadn't played in front of an audience for so long. I said to Ray [Danniels], our manager, at the end of that show, that it would have been a shame if this had never happened again. Because of course a few years previously I was convinced that it was never going to happen again. And in that show we just looked at each other and it was just so very powerful and emotional.

You talked earlier about transporting yourself to shows, and you've said that since getting on a bicycle you've developed a whole new affection for America. Meaning?

For twenty years all I saw were arenas and hotels and the tour bus. Songs like 'Middletown Dreams' could never have happened if I hadn't gone out on my bicycle and realised there's a Middletown in every State. I met and continue to meet people on an informal basis like that, in a hotel or a gas station or whatever. These interludes with real Americans outside of any other context, well...you get talking to somebody and think, this is the real America, you know. There are a lot of experiences and images that I could never have got without going out there and finding them. I travelled here on my motorcycle because I want to write a book about this tour and I thought there's no better way to start the book than with a road trip. So I rode the bike from LA to here, to Nashville. It took three days, two thousand miles, it was a slog, but I wanted that immersion in America and the American road, especially to begin the tour, because to me there couldn't be a better set up to build the tour from.

You're finally coming back to Europe. It must be a sort of homecoming for you, having lived in London in your teens.

I was in London for eighteen months. I was eighteen, so it was such an important time for me. I'd never been away from home before. I played with some bands, and became so disillusioned with the music business that when I came back from there I was prepared to work with my dad for a living and play music part-time. I worked in the farm equipment business and I accepted the reality. I wasn't going to sacrifice my ideals musically, I made the choice that I would work for a living, then I'd play the music I loved at night. Then Rush came along the following year. That was nineteen seventy-four - thirty years ago.

The Sword & Sorcery Phase

By Geoff Barton

Rush has their first taste of success in 1975, when they changed from being a basic hard rock power outfit and became something altogether more mystical and grandiose. Geoff Barton claims the band have never bettered the days of 'By-Tor & The Snow Dog'.

Whenever I'm wandering around my local shopping precinct (the Elmsleigh Centre in Staines, Middlesex, if you really want to know) I always find it very hard to walk past the beguiling Games Workshop emporium without giving it a second glance.

More often than not I find myself pausing to peer at the earnest young lads inside, grouped around the gamestable and plotting elaborate military manoeuvres with their miniature orcs and elves. And all the while I've got a wistful glint in my eye.

That's because, way back in the mid-70s, I too was obsessed by the genre of sword and sorcery, so the sight of my friendly neighbourhood Games Workshop in full, fantastical flow always brings some whimsical memories rushing back.

I admit it: I used to live in a mad world of demons and wizards; dungeons and dragons; broadswords and battleaxes. I used to devour novels by Robert E Howard, creator of Conan The Barbarian. I knew every word of The Hobbit by heart. I had all of Michael Moorcock's books; I was enthralled by the author's cunningly conceived 'Multiverse', and I loved his character Elric of Melnibone (the albino king with his soul-devouring rapier, Stormbringer) best of all.

Of course, all this has been reduced to utter nonsense these days (I blame Terry Pratchett). But it made perfect sense to me, way back in the mists of time...especially in 1975, when the call of the Great God Cthulhu somehow wafted over to conservative Canada and summoned up 'Fly By Night', the second album by Toronto trio Rush. By Odin's beard! I immediately found myself infatuated with this band.

Earlier, Rush's self titled debut had more or less passed me by. With John Rutsey hitting the skins alongside guitarist Alex Lifeson and bassist/vocalist Geddy Lee, I had pigeonholed the group as a fair-to-middling hard rock power outfit in the classic British mould of Cream and Led Zeppelin, although Lee's chipmunk squeal certainly set Rush apart from the pack. Was that a good or bad thing? It was difficult to say, but I didn't worry about it unduly at the time.

However, 'Fly By Night' marked a Rush Renaissance - yes, with a big capital 'R' - as the band adopted a brand new, deeply flamboyant mind-set. Having acquired a flashy, twirly-moustached drummer called Neil Peart, the three-piece shifted direction dramatically. They became mystical and grandiose; enchanted and other-worldly; weird and wondrous. They garbed themselves in flowing kimonos, voluminous blouses and satin trousers. They began to sing about 'misty mountains' and 'sighing trees' and places 'where the Dark Lord cannot go'. They visited the tobes (tobes?!) of Hades and traversed the river Styx. And, of course, they related the tale of the cataclysmic clash between By-Tor and the Snow Dog. I listened to this epic struggle between good and evil countless times on my unwieldy hi-fi headphones, the initial skirmishes between the two mythical creatures first resounding in my left ear, then running across the forehead to my right ear, the final denouement taking place in the epicentre of my cerebellum.

Wow! This was the battle of Helm's Deep distilled into the single groove of a humble vinyl record. Nice work, producer Terry Brown. Suddenly Rush had become my favourite band in the entire world.

The love affair continued, from 'Caress Of Steel' (didacts and narpets, anyone?), via the jaw-dropping '2112' (the tour de force concept piece where Rush really assumed control of my senses), right through to the live masterwork 'All The World's A Stage' (straightforward, good-time rock'n'roll tracks such as 'What You're Doing' and 'Finding My Way' now offering an agreeable counterbalance to Rush's more grandiloquent rallying calls).

Then came 'A Farewell To Kings', my favourite Rush album of them all. As a writer on Sounds, I actually spent a few days with the band while they were making '...Kings' down at Rockfield Studios in Monmouth, South Wales. I remember venturing into a cow shed adjacent to the studio where a vast, elaborate drum kit had been set up. Birds twittered outside and a gentle breeze blew up, rustling in through the doors and causing some of Neil Peart's giant wind-chime devices to tinkle back in response - listen carefully, and you can hear it all happening on the record.

Yea verily, there be magick in the air.

But sadly I fell out of favour with Rush when they came up with the 'Hemispheres' album in November 1978. I should have known something was afoot when Geddy Lee told me in February that year: "Synthesisers are going to play a bigger part on the new album. That's something I've been working on. I've just acquired an Oberheim Polyphonic and I've been trying to figure out how to play it...I think I've got the hang of it now. It can make endless sounds, and I'd like to incorporate it into the album..."

These were desperate, tragic times. When 'Hemispheres' was released, it sounded as if Rush had metamorphosed into nothing less than a turgid, torturous techno-rock trio. Plus, to compound the agony, I didn't understand the 'conclusion' to 'Cygnus X-1', one of the outstanding tracks on '...Kings' that the band had promised to wrap up on 'Hemispheres'. I'm a simple sci-fi soul; all I wanted was to find out what had happened to the spaceship (the Rocinante) after it had plunged into an imploding star - a black hole. But instead of admitting the Klingons were to blame in a tidy Star Trek-style ending, Rush embarked on a baffling progressive-rock marathon packed full of allusions to Greek mythology. I'm sorry, but I didn't understand a word - or a note - of it.

It took me ages to gather my senses and come to the grim conclusion that Rush weren't my No.1 band any more. I eventually plucked up the courage to face down Geddy Lee in late 1981, backstage at the Brighton Centre on England's south coast, when the band were on tour to support their 'Moving Pictures' album. The intro to the eventual article summed up my dilemma succinctly: 'After the gold Rush: Geoff Barton writes his first Rush feature for (count 'em) three years and asks, Is there life after Maple Leaf Mayhem?'

Despite the passage of time, Lee, to his credit, remembered my review of 'Hemispheres' very clearly: "You couldn't decide whether the album was the best or worst thing we'd ever done, right? That was the most disgusting case of fence-sitting I've ever come across!"

But Geddy, I pleaded, all I really wanted from you was a shipshape conclusion to an enjoyable little sci-fi tale about a doomed spacecraft. Really, was that too much to ask?

"It took a left turn, that tune," Lee admitted. "We did the first part on '...Kings' and that was great, but when we sat down to write the second part we found that we really didn't know where to take it. But we'd already said 'to be continued', so we had to do something...Neil [Peart] had been working on this whole Apollo/Dionysus thing for some time. It wasn't supposed to be part of 'Cygnus...', but then after several discussions we thought, well, maybe we can combine the two ideas and kill two birds with one stone."

My review of the Brighton show summed up my aversion to Rush's new direction: 'They have become a horrific hark-back to the early 70s,' I wrote, 'when cold "technique", finger-flashing "expertise" and mind-boggling "musicianship" were revered above all else, and for all the wrong reasons.'

In the end, I found myself in full-on begging mode with my one-time Rush hero. "Some time in the future," I whimpered at Geddy pathetically,"is there any chance of the band composing some more sword and sorcery numbers? In fact, just one would do. It can be as long or as short as you like. Pretty, pretty please?"

"It's unlikely, to be honest with you, Geoff," Lee replied. "That's the difficult thing about being a fan of a band - any band. I've done the same sort of thing myself: you sort of tune into a group at a particular moment; you're drawn by the material they were playing at that particular stage in their career."

In fact Geddy was spot-on with his comments. But I wasn't listening.

"From our point of view," he continued, "we can't stay in that moment. That's why so many groups break up - they figure, well, we'll keep on doing the same thing. But after a while they become bored and complacent, and stop caring about what they put on record. And their audience stops caring too."

Geddy's argument was an entirely convincing one, and it's absolutely true to say that Rush have strived for, and attained, numerous fresh peaks since (to paraphrase Air Supply) I found myself all out of love with the band.

But that doesn't sway my belief that, out of every single one of Rush's multifarious musical phases, their sword-and-sorcery period was the best. After all, the band still play '2112' - and it remains the Goddamnblasted highlight of their modern-day set. And, fittingly, there's no sign of bewildered Greeks bearing convoluted prog-rock gifts. No sign at all.

As Conan The Barbarian would undoubtedly say, while slyly digging a rusty dagger into your ribs: "Ain't it the truth, by Crom!"

The Art Rock Years

By Dave Ling

For many Rush fans who had thrilled to the likes of 'Hemispheres', the band's 80s love affair with technology caused their love affair with the band to cool. Chilling tale: Dave Ling.

For many Rush fans, the mid-period between 'Hemispheres' and 'Power Windows' represents the band's golden age. As you're by now already aware, 'Hemispheres' marked the beginning of "desperate, tragic times" for our own Geoff Barton, who had championed them in the pages of Sounds since the early days. But I beg to differ with his passionately expressed viewpoint, and doubtless so will many of you.

Hopefully Geoff won't hate me too much for pointing out the obvious, but this dichotomy is probably best explained as an age thing. Don't get me wrong, I too was left reeling by the trio's sci-fi period - the silly cloaks, the stack-heeled boots, the other-worldly lyrics and especially the immortal, spell-binding concept-album jiggery-pokery of '2112' - but being a teenaged reader of Sounds at the time of 'Hemispheres' was a very different proposition to analysing music for a living.

'Hemispheres' was the first Rush record that I bought and fell in love with; the group's earlier works were all investigated retrospectively. That probably made a big difference. If for no other reason, Rush's albums between 1978 and 1985 (yes, I know I'm pushing this time-frame in the case of the latter) represented the band's golden age to many of us simply because we felt like a part of them. I absolutely worshipped 'Hemispheres'. From the moment it arrived in my life it barely left the turntable. Rush were just...different.

Its Hugh Syme-designed sleeve - a naked man astride an enormous human brain, reaching out to another human wearing a pinstriped suit - made it fundamentally more cerebral than the other stuff I listened to at the time: Status Quo, The Sweet, Purple, Sabbath. 'Hemispheres' was music that wore its graduation gown over a denim cut-off; a sophisticated yet deliciously energised noise, it made you want to scream aloud: Yes, I'm a rocker, don't pigeonhole me as just another mindless moron (although, thinking about it now, I probably still was one at the time).

As Geoff has already pointed out, 'Hemispheres' was the album with which bassist/vocalist Geddy Lee really began to experiment with keyboards. (Lee undoubtedly ventured way too far in that direction, although in my own estimation not for several albums yet). The track that took up the entire side one of its original vinyl edition was 'Cygnus X-1, Book 2'. Ambitious and riveting, it relates the battle of heart and mind in 18 minutes of lavish, muscular and thoughtful pomp rock. I fully accept Geoff's observation that it offers no real conclusion to its predecessor, 'Cygnus X-1, Book One - The Voyage', from the previous year's 'A Farewell To Kings' disc, but that's relatively unimportant - whatever happened to poetic license?

My fate as a hopeless Rush fan was sealed the following summer during a family holiday to Canada. The band just happened to be playing a couple of addon shows at the end of their 'Tour Of The Hemispheres' while we were in their home town of Toronto, and my cousins offered to take me along. To call the experience mind-blowing would be an understatement. If memory serves me correctly, the group played the two halves of 'Cygnus...' back-to-back during the course of a quite staggering show. 'The Trees', an eloquently worded tale about the pitfalls of superiority and selfishness, also appeared in the set, which was rounded off by a haunting, epic 'La Villa Strangiato'. That gig sealed a love affair that, although it often heightened and dramatically cooled over the ensuing years, has remained fundamentally important.

Amazingly, 1980's 'Permanent Waves' was a match for 'Hemispheres'. A track from it, 'The Spirit Of Radio', even took Rush into the UK Top 20 for the first time. Presumably by now Geoff was pulling out his hair by the clump, as the band finally severed their last remaining ties with sci-fi and moved into the field of highly polished, intelligent art-rock. '...Radio' combined incisive lyrics (how ironic that drummer Neil Peart would vilify the integrity of broadcasters just as his own band finally made their playlists) with an unusually commercial yet resolutely rocking song structure; the keyboards remained, though. But while some Rush die-hards howled betrayal, the incoming hordes gratefully took their seats in the front row of Hammersmith Odeon.

Released in 1981, 'Moving Pictures' maintained both the group's commercial and artistic growths. Synthesisers were liberally plastered all over the likes of 'Tom Sawyer', 'Red Barchetta' and 'Limelight', although still not at the expense of Alex Lifeson's thrusting guitar. But the material was so good that they could've played it on a Stylophone for all most of us really cared.

Meanwhile, Rush shows went from strength, the addition of specially filmed movies for '...Barchetta' enhancing classic rock riffery and transporting their storytelling skills into a whole other realm. The venues were bigger than we were accustomed to, but Rush still felt like 'our' band. If anything, having side two of their live album 'Exit...Stage Left' recorded on their British tour even helped to strengthen the bond (although the less said about its murky sonics the better).

Something changed with the 'Signals' album. By 1982 Rush were using keyboards as a primary instrument, often relegating Lifeson's contributions to that of almost an after-thought; opening track 'Subdivisions' was almost devoid of guitar. The record's saving grace was the quality of tracks like 'New World Man' and 'The Analogue Kid'.

The same reservations and recommendations applied to 1984's 'Grace Under Pressure'. 'Distant Early Warning' might have been one of the best songs the band had ever written, but Lifeson was in danger of being rendered obsolete by waves of dancing, pulsating keyboard. Long-time Rush producer Terry Brown had by now been shown the door - the first time Rush had worked with anyone else since 1975 - in favour of Peter Henderson (Supertramp/Paul McCartney). Once again, the likes of 'Red Sector A' and 'Kid Gloves' kept cries of 'sell-out' at bay, but it was all beginning to sound a very long way indeed from 'By-Tor & The Snow-Dog'.

For many Rush fans, the introduction of ex-Gary Moore collaborator Peter Collins for 'Power Windows' in 1985 was the final straw. A tongue-in-cheek single called 'The Big Money' still more than hit the spot, but for a band that once had so much identity, the cold, impersonal feel of the 'Power Windows' album was a shock; the embracing of technology aligned to virtuoso performances was starting to seem more important than energy levels. Worse still, the songs were infinitely less riveting than during the group's heyday. Like Geoff Barton before me, I decided it was time to leave Rush to it...

The Back-To-Basics Years

By Malcolm Dome

After their rise to success in the 70s, being derided as 'uncool' and out of step in the 80s, and searching to establish a direction in the 90s, Rush now find themselves praised by - and influencing - a number of new prog kids on the block. Let's go round again: Malcolm Dome.

It was a shock, honestly. It's 1996, and I'm on the phone to Rush guitarist Alex Lifeson. I've just been listening to his debut (and so far only) solo album 'Victor' - and it rocks!

"But Alex," I splutter in near ecstasy, "your album? it rocks!"

The 'eloquence' of my statement-cum-question might have been lost somewhere between my brain and my mouth, but the point was still pertinent. Rush had long since had to suffer any criticism; they were so good that you got the feeling they could do a Black Lace tribute album and make it sound erudite, articulate and downright classy. But did they still do 'rock' in the 1990s?

"You know," Lifeson responded, "I'm glad you said that. Because much as I love what we do in Rush, on my solo album I wanted guitar, and then some more guitar!"

Maybe that's what was missing from the Rush repertoire as they started to clamber into the last decade of that now dead century; the guitar had been pushed somewhat to the back of things, and was difficult to hear above the clang of keyboards and electronic dazzle.

The mythic metallic pomp of the Rush we'd grown to love in the 70s had given way to a sharper, more streamlined sound in following decade, and another decade later they were more esoteric in their instrumentation. If the 70s saw them aligned to Styx and Judas Priest, and Rush in the 1980s were defined by an affinity with The Police, in the 90s they were firmly alongside latter-day King Crimson.

Rush had ended the musically threadbare decade that was the 80s with the comparative disappointment of 'Hold Your Fire' in 1987 and 'Presto' two years later. Both records were too clinical for my rather rusted taste. But I did see the band live in Montreal in '88 and they could still burn bridges with their passion for performance.

The first album of the 90s was 'Roll The Bones', arguably their most satisfying since 1984's 'Grace Under Pressure'. Strangely, so many of the lyrics here dealt with death and dark subject matter; some people may read something significant into these words, because drummer Neil Peart, as usual, was the lyricist, and it was as if he was seeing several years into the future, when his daughter and wife would die within months of each other.

'Roll The Bones' itself nodded toward the trend of the day with a brief rap section (Rush displaying humour?!), and 'Bravado' and 'Neurotica' were well thought-out, evocative, albeit claustrophobic pieces. This album was to prove significant for UK fans of the band, because in April 1992 the trio played a storming gig at Wembley Arena. It proved to be their last show over here. Until now - 12 long years without a sniff of Rush on stage in Britain. Gone were the days when every single year, Rush would be the early favourites to headline at Donington, and despite their detestation of outdoor shows.

"We hate them," Peart told me in Montreal in 1988. "The sound is always so poor. We'd rather do multiple dates indoors at a small venue than subject ourselves and the fans to such poor conditions."

True to their word, Rush have never played an outdoor show in the UK - and after 1992, they studiously avoided us altogether. But the albums kept on coming, and the quality of them was never in doubt. With musicians like these three, nothing less than a masterpiece was expected every time. We didn't always get it, but at least the new albums kept our attention every time.

By 1993's 'Counterparts', Rush could claim that the line-up then had been together almost 20 years - a major achievement. But why had they locked things down so well together?

"I guess we have a mutual respect," Lifeson feels. Peart offers a view from a different angle: "We give each other space, we don't live in each other's pockets. We're mature enough to know that this life we lead isn't real." You can't imagine that coming from any other drummer.

'Counterparts' told of a band who, yet again, were being driven forward by the shifting times. Always restive, now it was grunge and the alternative scene that fascinated them. Listening to the record, it was as if Rush had been both galvanised and challenged by it. I did get the feeling that they lived in perpetual fear of being made obsolete. So they adapted to the times. AC/DC prospered through sticking rigidly to their strengths; Rush didn't really know their strong points, only a desire to push on musically. Throughout it all the fans' dedication and devotion was almost unshakable.

But 1996 was to prove a turning point. Rush released the complex 'Test For Echo', started touring, even hinted at a welcome return to Britain. Then Peart suffered his double tragedy. Lifeson and Lee gave the drummer the space to grieve and decide for himself what he wanted to do - if anything. Lee decided to explore his own musical topography with 2000's 'My Favorite Headache', which, really, was indistinguishable from a Rush album.

And then something amazing thing happened: Rush became cool again. It started with young bands like Cave In and Opeth praising them, and also citing them as an influence, and it grew from there. One band, Coheed & Cambria, even boast a Geddy Lee soundalike in vocalist Claudio Sanchez. And as a whole new era of prog rock began to open up, Rush were pulled back into the limelight. There was even a genuine buzz about their 2002 album 'Vapor Trails' - possibly the first time that a new album from the trio had been so anticipated in nearly two decades.

While 'Vapor Trails' was a little more stripped-down than some of what Rush had done before, it wasn't the band's present, or immediate past, that was fascinating people again. In an ironic twist - which probably wasn't lost on Lee, Lifeson and Peart - those new bands who were worshipping at the altar of the Rush's back catalogue were inspired by the band's sword & sorcery imagery and cod-epic music of the 1970s. How strange that, having spent so many years carefully reinventing their sound and style, Rush were being hailed by a new generation - one far removed from the sensibilities of 'By-Tor & The Snow Dog' - because of their early period.

So, here we stand in 2004. Rush have just released a covers album called 'Feedback' recalling their own influences - from Buffalo Springfield to Cream, via Blue Cheer and The Yardbirds - and they're in the throes of a tour, celebrating 30 years with the current line-up, that at last brings them back to the UK. And still their appeal is almost unfathomable. Intellectual, slightly distant, low-key, they don't exactly seem like the sort of band to endear themselves to rock fans who love passion and personality. But maybe even that's about to change.

Lifeson's arrest after a fight at a Florida hotel last New Year's Eve sparked both surprise and a sly thumbs-up from fans; maybe in middle-age Rush will discover sex, drugs and fisticuffs. There again?

Whatever, Rush's stock is higher now than it's been in two decades. Who can argue that they don't deserve it?