Three Stages Of Rush

The band's first three concert films, 'tarted up and boxed together', provides a great record of their evolution

By Jon Hotten, Classic Rock, Summer 2006; transcribed by pwrwindows

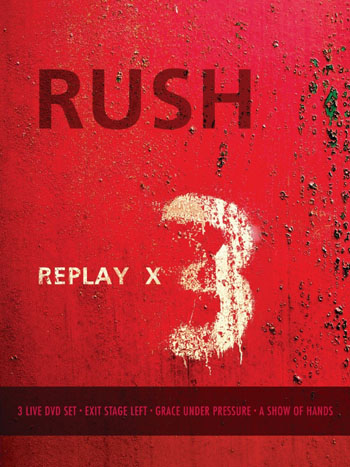

RUSH

Replay x3

Universal

Rush have defined themselves with recordings of their live performances.

Originally it was with the tremendous double albums that came along after every three or four studio releases, each one an event in itself. For those in thrall to the band, these were fetishistic offerings in shining gatefold sleeves, with extended versions of muchloved songs cut into acres of shimmering vinyl. They invited solitary retreat to a darkened room for many hours of geeky aural bliss... (Did Neil hit a different cymbal here? Has Alex tweaked the guitar solo a bit there? What did someone in the crowd just shout at Geddy?).

Those live albums added to the mystique of a band that really should not have had any mystique and yet somehow did. For here were three men who defined 'ordinary'. Compared to totemic performers like Robert Plant or Dave Lee Roth, the Rush trio of Geddy Lee, Alex Lifeson and Neil Peart looked like three guys who'd arrived in the concert hall by mistake, who'd taken a wrong turn en route to a Trekkie convention or a speed-dating evening.

Rush didn't write songs about sex 'n' drugs 'n' rock'n'roll, either (unless you count Limelight, which thumbed its nose at the entire concept). Instead Peart concentrated first on apocalyptic sci-fi stories (2112, Xanadu) or third-person narratives (Red Barchetta, Tom Sawyer), and later on bigger social targets (Big Money, Subdivisions). And then their was the music; often distant and unapproachable and almost baroque in its complexity.

Yet Rush succeeded because the band, for all its faults, adhered strongly to their own internal logic. Once you 'got' Rush, they simply never disappointed. With every new live album, they'd evolved considerably and always in a straight line. Those live albums of the 70s and 80s - All The World's A Stage, Exit Stage Left, A Show Of Hands - were landmarks, not contract fillers.

Now the DVD age defines Rush, or so their sales suggest. Their concert films sell in the quantities that their live albums used to. Bedroom headphone porn has become widescreen, surround-sound porn. Rush fans have got kids and houses and consume their concerts in front of the telly. The band have released a series of set-piece shows (Rush In Rio is five-times platinum, R30 three-times platinum), and now the first three of their concert films - Exit Stage Left (1981), Grace Under Pressure (1985) and A Show Of Hands (1988) - have been tarted up and boxed together, or 'rebadged', as the great Alan Partridge might put it. An audio CD soundtrack of the Grace Under Pressure show plus reprints of the tour books are also included (although not in this review copy, but we'll take their word for it).

It's enlightening to play them back-to-back. That straight-line evolution is not without humour. In 1981, the band had just cut Moving Pictures, the first of their albums to reflect the new decade: out with the 70s sci-fi, in with the glistening techno remoteness of the age. Alex came on stage in a Miami Vice jacket.

Geddy stood behind great banks of keyboards. At one point, both he and Alex played double-necked guitars. Neil Peart was just a head bobbing up and down in a sea of drums, cymbals, chimes and other percussive paraphernalia. They still performed Xanadu without knowing winks between them.

By 1985 they had made Signals, their most divisive yet possibly greatest album, and its grander successor Grace Under Pressure (a title Peart pinched from that old macho glumster Hemingway). The corresponding live show was leaner, harder, less celebratory. They all wore Miami Vice gear, and the set list was filled with songs about paranoia - The Enemy Within, Witch Hunt, Distant Early Warning.

By 1988 they still wore the Miami Vice gear; Neil added a provocative plaited ponytail. Yet they were men more at ease with themselves and their place in the world, perhaps because they were now utterly confident that their audience would follow them anywhere they chose to go. In among the accomplished new songs, they could scatter bits of 2112 and La Villa Strangiato and they could laugh with glee as they played them.

These three live shows reflect an artistic evolution.

Given the subsequent personal tragedies endured by Neil Peart and naturally felt by his colleagues too, it must seem entirely insubstantial. The Rush of a decade-and-a-half on are more organic, less hung up, and they can look back on these shows like a family leafing through its photograph album to remember some uncomplicated and resonant times.