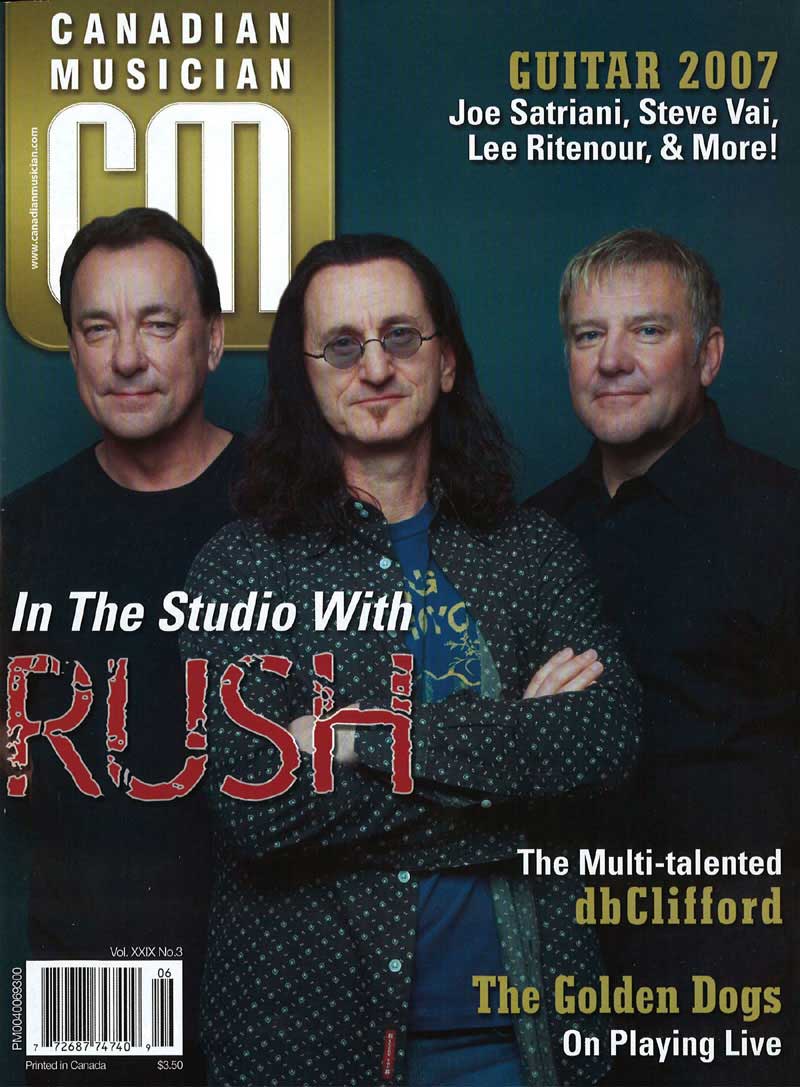

In The Studio With Rush

By Kevin Young, Canadian Musician, Spring 2007

Imagine spending five weeks producing one of the first bands you saw in concert. That's what Nick Raskulinecz experienced when he got the call to produce Snakes and Arrows, Rush's latest record. "Nick as very young the first time he saw us," says guitarist Alex Lifeson. After hearing the band was working on a new record, Raskulinecz asked his management to approach them. Initially, they explained that they already had a producer, but two months later the situatin changed - Rush called back. For Raskulineca it was a dream come true. "For both he and Rich Chycki, our engineer, there's a whole era of Rush that's close to their hearts," says Lifeson. With that perspective, Raskulinecz approached the new record with the intention of concentrating on capturing very specific characteristics that typified the feel of earlier records.

Assembling that kind of experience, says Snakes and Arrows Engineer/Mixer Rich Chycki, had great benefits for the process. He first met Rush while working on a recording of 'Closer To The Heart" for the CBC's Tsunami relief show and has also worked on it's R30 DVD. Wwhen we spoke he was actually in the process of mixing Snakes and Arrows in 5.1, at Mixland Music and DVD in Wasaga Beach, ON. "In this situation the benefit was that there was no translation required. Nick would say 'this is what I'm looking for' and I could just dig in and do it. Eveyone shared a common vision so it worked out really well."

That vision, and Raskulinecz's energy, propelled the sessions forward. "When I got involved they had already been writing and doing pre-production", says Raskullinecz. "I went to Toronto for two different one-week trips for about two and a half to three months apart. Then we took a three-week break, met up at Allaire Studios and tracked the whole record in 36 days.

The second concert I ever saw was the Moving Pictures tour. I was 12", he continues. The industry, and how we use and view music has changed unalterably since then. Though the rock and roll mystique has taken a bit of a beating, Raskulinecz didn't let that interfere with his efforts to capture all the old magic, fire, and mystique of Canada's most successful power trio on record. There's a lot of talk of the death of the album these days - the less value is attached to music, the more the record seems doomed. Much of the initial justification for using illegal P2P was that there were fewer tracks worth listening to on any given record and so, for value for your money, you'd be better off to buy only the single. That not the case with Rush. They just don't do throwaway tracks. nor do they write singles or individual songs, says Lifeson. They make records.

"Everything is connected, and a lot of it has to do with the thematic connection of Neil's lyrics. It's always been about the albums for us, and I don't see that changing." Lifeson says. Beyond being what they do, it's what their fans want, and they've built a relationship and nutured it carefullt for too long to lose site of that. "I think we're solidly where we should be with this record."

Recorded at Allaire Studios in Shokan, NY, and mixed in LA's Ocean Way Studios with Raskulinecz and Chycki, the album is a return to the feel of older Rush records, Raskulinecz says. Known for his work with the Foo Fighters (In Your Honor, One by One) and his energy and animated production style, Raskulinecz is no stranger to producing high profile projects. Still, he gets chills thinking about the Rush sessions. Unlikr some projects Snakes and Arrows didn't wear him out, he explains. "I'm energized and refreshed. I'm proud of this record, and the three of those guys for taking a chance with me. These guys can get anyone in the world, man. It's Rush - are you kidding me? I get to work with one of my favourite bands. We had a blast."

Originally, the plan had been to go to Allaire only a week to record drums, but before the end of the first night they decided to stay. The vibe and seclusion of it was a big part of the allure. "It was one of the most inspiring places I've ever been to make a record. Hell, our cell phones hardly worked. We lived, breathed, ate, and slept the record." he says - working from roughly 10 a.m. to whenever they wanted to, sometimes heading into the control room at 2 a.m. if the urge struck them. When we spoke, just prior to the release of the Snakes and Arrows first single, "Far Cry". Raskulinecz was still having trouble believing just how smoothly the process went. "The whole thing doesn't even seem like it happened, because it went by so fast and it turned out so great," he laughs. "It was amazing." So much so, they quickly became a very tight knit team, leaving the mountain a handful of times.

The band nicknamed you 'Bouge'?

Cause of my air drumming and making drum sounds. I always go...Bouge.

What's 'Bouge' the sound of?

It can be a snare drum or tom.

Being such a big fan of the band, were you intimidated at all?

I was the most nervous the first time I met them, but within 10 minutes they made me feel totally comfortable. One of their managers picked me up at the airport, took me to Geddy's house, dropped me off in the driveway and said 'call me when you're done.' We talked for two or three hours about music and recording techniques, and really got a feel for what everybody was thinking, and during that conversation I told them exactly how I like to do it - I like to join the band.

Did you impose a process on the sessions, or was it a meeting of the minds?

I do it the way they were doing it already, so we just fleshed out how to move forward. I like to spend a lot of time on pre-pro and get everything worked out before we go into the studio. That's why we were able to track the record so quick.

So many people are making records in their living room and producing themselves - what do you think someone who wants to produce their own records could learn from watching you work with players of this calibre?

Just having that objective voice, you know? The music will never be as close to me as it will to those three guys, so it's a lot easier for me to say 'that could be different, or that could be better.' It's really, really hard to produce yourself in a lot of ways. I don't think that's producing. I think you're just recording when you're doing it that way.

What do you see as the difference between just recording and producing?

If you're producing yourself, you're never really able to stand outside of it. People that make records in their houses, and have never worked with producers, or worked in studios, have no idea what they're missing out on. There's a wealth of knowledge that producers like myself have because we've been doing this for so long. Getting it done right, he says, is an art. There's a right and wrong way to do things when it comes to engineering. You might not realize you're doing it wrong when you're doing it in your bedroom and it sounds killer, and then you give it to somebody else to mix in a recording studio and you go, holy shit, that sounds terrible. What was going on here? Well, your house isn't tuned. Your bedroom wasn't built to be a room to listen to 65 hz in and guitar tones and drum sound and vocal sounds. Granted, some people make great sounding records in their house, so kudos to them, but it doesn't really work like that for me.

Feel is very important to Raskulinecz - not just the feel of individual performances, but also the overall vibe of the sessions. "When the sound is right - and if you're a musician you know what I'm talking about - if the sound is right and everything feels right, you're going to deliver the goods." And getting the band to deliver the goods is what Raskulinecz focuses on...

That's what my job is. After you get everything arranged and get the songs figured out, you put your pom poms on and be the cheerleader for the team. There were a lot of really inspiring moments making this record: watching Neil Peart play drums like he does, and standing three feet away from Geddy Lee when he's recording bass tracks. It's one of the most inspiring things I've ever been a part of. We really made a performance record - they're playing everything. There's no audio manipulation, no sitting in front of a computer for hours and moving things around and fixing things and replacing things. There's zero of that on this record. These guys don't need that technology. Basically, the main reason we use it is because of the speed. It's a hell of a lot quicker to make records than it is with tape. There's no comparison.

What's the difference between editing to get the performance you want as opposed getting good solid performances from the players straight up?

It just feels different. You can cut something up and make it perfect, but all the records I know and loved and listened to when I grew up weren't perfect. You can hear those imperfections in the old performances: out of tune vocals, missed drum hits and stuff like that. When you just listen to music none of that matters. The song is what's important. I don't want to get absorbed into the technology, I don't even think about the technology. I just think about the song and how it feels. That magic you get when you hear a great song, to me, that's the most important thing. I don't care if it's perfect. It's how all of the instruments work together. When you listen to a great song, you don't hear each thing individually. You hear it as a whole.

You're really animated in the studio and really get into the performances?

I do. I'm a fanatical air drummer, guitar player, everything. That's how I do it. I'm standing three or four feet away from Geddy and I'm playing with him, same thing with Neil. I'm definitely all about feel. If it doesn't feel right, then it's not right yet. And I think that's how records used to be made. Like I said before. I try not to get overwhelmed by the technology, because the technology can take the song away.

What do you mean?

You become so wrapped up in fixing little things, but in reality they're not wrong, that's part of the vibe. You don't listen to music with your eyes. You listen with your ears. You look at it and there's the kick and there's the bass and you go, 'well I need to move that.' It's automatic. Your ears don't hear things the same way because your brain isn't processing it the same way.

How do you go about getting to the point in the relationship where you walk up to Neil Peart, Alex Lifeson, or Geddy Lee and say, 'you know, I don't like that?'

I pretty much did that immediately. I think that's one of the reasons that they went in my direction. After the initial meeting we went down into the basement and listened to some of the demos they were working on. I immediately said, "this could be better, that could be better, this could be different." And I think they were, like, 'holy shit, this kid just came in and, told us what he thought' instead of sitting there and telling them how great they were. Part of the producer's role is to be brutally honest, and hopefully you're in that position because the band likes your work. If I'm recording with the Foo Fighters, and Taylor doesn't nail a drum track, I tell him to do it again. If Dave isn't singing great, I tell him to do it again. It's exactly the same thing with Rush. Because I'm so familiar with their records, I know what they're capable of achieving.

For Raskulinecz, the biggest thing was to capture the feel of early Rush. That meant using their past work as a template to drive the process, getting deep into songwriting, arrangements, instrument choices - everything. "Everybody got equal treatment," he says. "Look, Neil Peart is probably the greatest drummer in the world, but if it doesn't sound right, or feel right, then he needs to go do it again. The very first day we did a drum track, and it was awesome. When he was finished, I said, 'okay, we got that and it's great, but what if you try it this way. He thrives on that.'

Raskulinecz also had a very concrete list of things to capture that make up Rush's sound and feel - Taurus Pedals on almost every song, for example. "For me, that's a huge part of the sound of Rush. We changed guitar sounds on every song to give every song it's own identity," he says, employing a lot of Lifeson's and Lee's classic guitars: Lifeson's tobacco sunburst ES 335, his Les Paul, his Telecaster, and Lee's original black Jazz Bass."

"We worked off the demos and Neil tracked to those," says Rasculinecz. "Some of the songs we cut with Geddy and Neil playing together on the floor. Then we started overdubbing guitars, and at that point, we used both rooms at the studio. Alex did guitars in one room and me and Geddy did vocals in the other studio. "Doing vocals and guitars simultaneously isn't usually the way Rush records, but it shaved roughly eight weeks of their process, Lifeson says. Then again, the whole process was a little different, he explains...

"Typically we'd go into a studio on the first day of writing and continue writing for 8-10 weeks and then move into a studio and start recording at that point." This process was more casual, Lee an Lifeson working three days a week, in five or six hour sessions for just over a month. "We only live a few blocks from each other. It was very relaxed and easy. We started last March and carried on that way for about five weeks. We went to Neil's place in Quebec and spent a couple days with him, went over the material and got a feel for the direction. Then we went into a studio in Toronto in May and worked for that month, continued writing and got caught up on the songs that we'd written."

Overall, it was more like the approach they took earlier in their career. "Ged and I wrote acoustic guitar and electric bass, which was very different from what we'd been doing for a long time. In the early days, that's how we wrote, but not in the last 20 years. There was an immediacy about the music. When you write on acoustic you know right away if it works or not and if it doesn't it's quite obvious to you." Although they worked from demos, they didn't allow themselves to be limited by them. "I didn't feel precious about anything. I wanted to start from scratch all over again."

He's come full circle, he explains. "I think the main approach to my sound now is straight into the amp, turn it up and go. There's something that just grabs you about it. It touches something. And I think that's why classic rock is such a successful format these days cause it's got all that in it."

Rush however, is hardly your average classic rock band. Anyone remotely familiar with the band knows the starman graphic - created by Hugh Syme, it first appeared on 2112 in 1976, a symbol of the abstract man against the masses. In many ways, it's symbolic of Rush's approach to music and career from the very beginning. After forming in 1968, the band immediately went through extensive lineup changes. It wasn't until Neil Peart joined in 1974 that the band solidified. Change has always been an integral part of their career, as is their individual development as musicians and their tendency to embrace new technology and musical styles without diminishing their own character.

"They've never gone backwards," Raskulinecz says, and his approach was never intended to change that. "It was never really about making them sound like old Rush. It's about making it feel like an old Rush record. Rush is never going to sound like it sounded. They're never going to make 2112 or Moving Pictures, or Hemispheres again - it's always been a forward-thinking band."

"I think the album does come across like that," says Lifeson. "It's hard for me to be objective about it, obviously, I hear elements of our whole history in the record." Still, the sound is fresh, he adds.

No surprise. From their early blues-tinged metal through their unique take on '70s prog and right up to their new release, Snakes and Arrows, they've never resisted evolution. Rush has survived changing musical and industry trends, the pitfalls of fame, and temptations of fortune, as well as personal tragedy. Along the way they've influenced countless musicians and rank fifth behind The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, KISS, and Aerosmith for consecutive gold and platinum albums by a rock band. Since Moving Pictures, arguably their most well-known release, they've consistently released new material and routinely sell in excess of a million records each time out, still pushing the envelope musically, for both their fans and themselves.

This time out, pushing the envelope took them to a place, Lifeson says, they haven't been in some time...

"For the first time in a long time I'm really eager to get back in the studio and do some more writing. It was such a wonderful experience. There was never any moment where I felt we were stressed out or up against the wall." A great deal of that, he says, was due to Raskulinecz's and Chycki's enthusiasm and their ability to keep things moving. "I would love to get back with that combination and do another record sooner than later."

The source of the excitement in the studio, judging from Raskulinecz's feeling about the album and the process, is the band itself, the chemistry that has held fans enthralled for almost four decades. It's a long, deep-seated chemistry - the kind few acts are able to maintain. "We're great friends. I've known Geddy since I was 12 years old. We've had so many of the same experiences," says Lifeson. "It's the same thing with Neil. We've gone through so much together - great experiences, difficult experiences, and, even at this stage of our lives, we're always laughing. It's just wonderful to be around each other, even before you take in work." And that work is still incredibly satisfying for all of them - more than ever, in fact. "There's a flow to this record, from beginning to end - it's really connected - a real album - we're really, really proud of it."