Back To Basics

By J.D. Considine, Guitar Word's Bass Guitar, July 2007, transcribed by pwrwindows

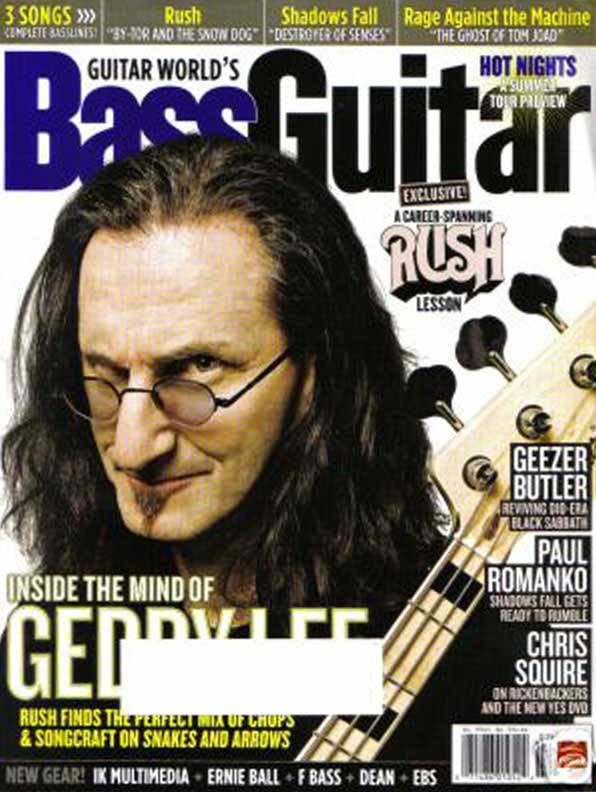

Almost four decades after their humble beginnings, geddy lee and company hire a hardcore rush fan to produce their nineteenth album. The result? Their best mix yet of old-school muscle, classic songwriting, and new-century sleekness. J.D. Considine looks under the hood.

"I think we learned a lot doing that fun little record, Feedback" Rush bassist Geddy Lee says, and on the face of it, his enthusiasm is surprising. Feedback was simply a collection of covers, eight oldies from the Sixties and early Seventies-that Rush used to play in their earliest days. At the time of its release, in 2004, the project seemed little more than a lark, a nod to what Lee described as "songs we played or dug at one point."

But as Rush took those tunes on the road as part of their 30th Anniversary tour, the band's appreciation deepened. "There was something about the way those songs were structured," Lee says. "Those were songs that we were weaned on, and they reminded us alot about some of the essential things about rock songs and rock songwriting that I think we'd drifted away from. It was a real inspiration for us.

"So when we started to write material for the new album, we said, 'Let's just start with Al [Alex Lifeson] and me, in my home, on acoustic guitar and bass-the way we used to write, you know, 15, 20 years ago. Or farther back than that, even." He chuckles, seemingly still amused at the thought of just how long Rush has been around.

"We used to always write on acoustic, and our theory was, if you can make an acoustic rock, adding the electrics is a piece of cake. And somehow you end up with a more fundamentally sound tune. So we tried that, and we just fe1l in love with working that way. It created a particular, intentional limitation to how the songs would be structured and how melodies would be written, because you didn't have that white noise hissing at you from the guitar side. I think that helped make these songs melodically strong."

By "these songs," Lee means the material on Snakes and Arrows, the 18th and latest Rush full-length studio project. Recorded with producer Nick Raskulinecz, it's the band's strongest effort in ages, combining the concise, intensely tuneful approach of 1989's Presto and 1996's Test for Echo with the chop-heavy virtuosity of older albums like 1976's 2112 and 1981's Moving Pictures.

From the semi-orchestral splendor of "Faithless" and "Armor and Sword" to the muscular punch of "Good News First" and "Working Them Angels," Snakes and Arrows is everything a fan could want from a Rush album-and then some. For instrumental fans, it's a garden of delights, thanks to the Neil Peart- driven "Monkey Business:' a gorgeous Lifeson acoustic guitar solo called "Hope" and a giddy bash dubbed "Malignant Narcissism." But the words are pretty impressive, too, with some strongly political writing, most notably "Wind Blows," [sic] a blues tinged meditation on how ignorance seems to be spreading "from the Middle East to the middle West."

Big, Bold Rhythm Section

What's most interesting about the album (particularly from a bass playing perspective) is how much Geddy it's got. Obviously, his vocalsremain a major part of the mix, but his bass also dominates, from the bright, midrange-heavy punch we've come to expect of his J-Bass to floo r-shaking subfrequencies that recall the glory days of his Taurus bass pedals.

"It's funny: mixing and getting the right balance in our songs is always, by far, the toughest thing about recording," Lee says. "We go through these phases where we get paranoid that the guitars aren't present enough and loud enough, and that was the way we were with Vapor Trails, where it was very much, 'Let's get the guitars really raw and steamy and rockin'.'

"On this album, after the songs were written, the production team of Nick and Rich [Chycki]-Nick in particular-was driving to put the guitar into its own space, so that the rhythm section can be big and bold and beautiful, and the guitars can be present without smashing up all those other elements of the rhythm section. And what it brought to light was that interplay between Neil and 1, and the fact that we can create a rhythm section that holds the melody- and holds the heart of the song- with the guitar free to play all those lovely inversions and unusual chordal parts that are Alex's forte.

"I thought that took a lot of maturity on Alex's part, to back away from the giant wall of massive, heavy guitar, in order to bring back some nuanced sound to his style."

Flamenco Chops

Meanwhile, Lee's own lines are surprisingly dominating and aggressive, particularly when he resorts to the flutter-fingered technique he describes as flamenco-style finger pick ing. "It started to evolve from [1993's] Counterparts;' he says. " 'Animate' was the first song I actually tried doing it with, and on my solo album [2000's My Favorite Headache], I started doing it more. With Vapor Trails it was really much more present. And now, it's just part of the toolbox."

Still, he's hard pressed to explain how, exactly, he does it. "It's hard to think about how you do it when you're doing it without thinking," he says. "I use two fingers, and it just depends on the kind of riff I'm doing. It's like a slap, but I'm not slapping with my wrist; I'm slapping with one finger, just back and forth, up and down. Sometimes I'll use my index finger, and sometimes I'll use my middle finger.

"The tone is a matter of what part of the body of the bass that I pick over. I'II do it closer to the neck if I want more of a slappy sound, or I'll do it over the pickup if I want it to be a bit more big and ratty. It's a weird thing- I don't think about it anymore when I'm playing it, so when you just asked me that question now, I'm trying to imagine myself doing it and reconstruct the stupid way my fingers attack the bass."

When it's suggested that he could put a special video track on the next concert DVD called "Close-Up on the Fingers," he laughs. "People keep bugging me to do my own instructional video, and I don't know. I find it hard to imagine myself in that environment, showing somebody the ridiculous ways I've learned how to play the bass. If I do it, it'll be called 'Don't Try This at Home.'''

Considering the level at which he plays, it's odd to hear Lee mocking his own technique. But he tends to sec his playing style more in terms of expediency than technique, and as such is a bit embarrassed to think that explaining how he plays could be considered educational.

''Why would somebody be interested in this?" he says. "It seems like a freak of nature, this whole style I've developed. But at the end of the day, it's the results, and I'm able to use it to create the kind of bass-scapes that I want to create, and I know a lot of people are interested in how I do that. So I guess it would be, at some point, appropriate to show someone."

Perhaps he could do it sports show-style, using close-ups and freeze-frames from concert footage.

"Right," he says, laughing. "Get one of those little marker things, and circle the fingers: 'Look at how terribly positioned my wrist is in this position. That's why I have tendonitis at the end of the tour.' "

The Jaco Bass

Jokes aside, the most important thing about Lee's bass playing is what he does, not how he does it, and nowhere is that more obvious than on "Malignant Narcissism;' a tune he wrote without even realizing he was doing it.

It all started when the folks at Fender, with whom he has an endorsement deal, sent a Jaco Pastorius-model Jazz Bass to Allaire Studios in New York, where the band was recording. "It's one of the coolest instruments I've ever played," Lee says. "It sounds amazing and plays amazing. I picked it up, and within a half an hour of owning it, I was just jamming with myself between vocal takes, and playing this riff that just felt so fun to play. Our producer was listening, and he started recording the riff through my vocal mic, just acoustically. He said, 'Man, that's a song right there you just wrote.'

"Neil happened to be hanging around, and he had this four-piece drum kit set up. So the next day we took that bass and the amp, sat down, and threw an arrangement together."

Because Lifeson was in Florida at the time, the initial track was just drums and bass. 'We said to ourselves, 'We already have enough music for this record, so if we do another instrumental, we've got to put a time limitation it.' So Nick said, 'Okay, two minutes and 15 seconds.' And we just threw this song together that actually came out at around two minutes and 15 seconds." In fact, the track is listed at 2:17- not bad for something just thrown together.

Lee admits that he's not much of a fretless player ("usually, it's a failure," he says), and that recording with the fretless J-Bass was "scary. Me playing a fretless bass is like, 'Jumpin' Jehosaphat, I hope you don't want any other instruments to this, because tuning's going to be really interesting.'" He laughs. "I figured if I played fast enough, the wrong notes wouldn't have time to be heard, really. The passing notes will just pass too quickly. I think it worked out well because it's such a damned beautiful bass to play and to listen to. Now everybody associated with the session wants me to get them one. That's a good sign.

"Fender was kind enough to make me a fretted version of it," he adds. "I'm going to play around with that as well, and bring them both out on tour with me."

The Return Of The Moog Taurus Pedals

Other than the Jaco J-Bass, Lee made almost no changes in his bass rig, relying mainly on his trusty 1972 Jazz. "There are no real effects on my bass, except on 'Wind Blows,'" he says. "In the pre-chorus or the B-verse-whatever you want to call those things- there's some overdubbed bass through a Mu-Troll, creating this kind of phased out, pulsating sound." Otherwise, he relied on his usual trifecta of an Avalon U5 tube D.I., a Palmer PDI-O5 speaker simulator and a Tech 21 SansAmp RBI preamp.

"But quite often I overdub a lower bass part on top of my bass, because on many of the songs I play chordal patterns, and some of those chordal patterns are high up on the neck, which adds an interesting, arpeggiated feel to the song. Like on 'Armor and Sword,' I'm playing chords and arpeggios through the entire chorus-nothing, really, that is a traditional bass part. So then, because of the lack of bottom, I'll go in and I'll play a bass track that's just kind of a soft, pulsating low-end complement. And then, of course, Nick will make me put bass pedals on there as well, to go an octave even below that, so that there's lots of pant-flap happening."

Raskulinecz, it turns out, is a big fan of Lee's old Moog Taurus bass pedals. "He was insistent that I bring out my old Taurus pedals, which of course I don't even own anymore because we'd sampled them long ago," Lee says. "I had to go and borrow them back from the people I sold them to. He wanted all those old, classic, Rush-sounding keyboards, and some of them I just kept making excuses about, because there was just no way on earth I was going to go there. 'Gee, Nick, I can't find that sample. Sorry!'

"Of course, by the end of it I fell back in love with them and couldn't wait to put them on more and more songs. I think the Taurus pedals are on all but two songs on the whole album."

"The other thing we rediscovered was the Mellotron," he adds. "At Allaire studios they had a beautiful old Mellotron. So we creanked it up on a couple songs, especially 'Faithless' and 'Good News First,' and they really added that whole orchestral feeling to them again. But it's the late-Seventies version of orchestral-it has more in common with King Crimson than with an actual orchestra."

A Real Rush Geek

Working with Raskulinecz was, says Lee, "kind of refreshing for us, because he was such a positive human being, and I really hadn't worked with a producer who had so many ideas so quickly in a long, long time. So he was a real treat."

He was also a dyed-in-the wool Rush fan, and that, oddly, took some getting used to. "It's kind of weird, the way he appeared in our lives, because we were kind of set to work with another producer," Lee says. "But the negotiations were not going well. So we said, 'Let's look around some more.'"

Lee had heard of Raskulinecz through his production of the Foo Fighters, and so the band requested his demo reel. "It was very impressive, just in the sense that someone made this that had a real love and knowledge of music. No matter what song or style, the reel was showing off good material or good sound or good production whereas a lot of reels we listened to, there aren't very good songs on them. And I'd think, Why would you want to hire a guy who can't tell the difference between a good song and a bad song enough that he puts kind of a mediocre song on his reel just because it's got a mix he did?"

Raskulinecz was in the studio with another band at the time but offered to take the red-eye from Los Angeles to meet with Rush. "Offered to fly up on his own dime, too, which is unheard of in the music business," Lee says. "So he flew in, and Alex and I met him at my house. He's such a lovable guy, you can't help but like him. Anyway, we played him a couple of our songs, and he flipped - but kept it quiet that he was really a huge Rush fan. He said he was a fan of the band, but"- Lee laughs-"I didn't know how seriously he was really a fan of the band."

Once they began to work in the studio, however, the band discovered that both Raskulinecz and engineer Rich Chycki knew the Rush catalog "intimately."

"Every once in a while, we would hear these two guys singing lines from songs I had forgotten that I had even written," Lee says. "They were singing the words from 'Chemistry,' fer cryin' out loud, from the Signals album. I'm like, 'Chemistry'? Jeez, that's obscure. That happened all the time.

"And in the evenings sometimes, when we were doing bed tracks, Nick would want to jam every night. So everybody's in there jamming, and of course those two always want to play Rush songs." He chuckles. "It was really sweet, actually. Never did I think we would work with someone who was one of our fans.

"But we found the right one to do it. And it meant a lot to him to do this record. He put his heart into it. And I remember when he left after that first meeting, he said, 'I will not let you down.' And he didn't."