Neil Peart's News, Weather and Sports

The Drums of October

NeilPeart.net, November 2008

|

Final rehearsal, Buddy Rich tribute concert, Oct. 17, '08 "Look ma - I'm smilin'!" |

In my time, I have climbed some serious mountains, from hiking to the top of Mount Kilimanjaro and bicycling over the Simplon Pass in the Alps, to facing down the uphill battles that life throws up in all our paths. However, one of the hardest climbs I ever had to make was just four steps - up to the stage of the Hammerstein Ballroom in New York City, on the night of October 18, 2008.

In forty-three years of playing drums, I have walked onto thousands of stages, of course, and I am always tense and anxious - tense with determination to play well, and anxious about not playing well. But this stage, this performance, was, as my teacher Freddie Gruber would say, "a whole other thing." Earlier that day, friends asked me how I was doing, and I shrugged and said, "Terrified!" They laughed, but that was a pretty accurate confession.

I felt I had a lot to live up to on that stage - the weight of expectations, my own and the audience's, and of course, the peerless drumming deity under whose name we were performing: Buddy Rich. I wanted to do my best - better than my best! - and I would only have one chance: right now. The house was full of great musicians, in the band and in the crowd, and, oh yes - the show was not only being recorded and filmed, it was streaming live on the Drum Channel Web site, all over the world ...

So as I stood at the bottom of those four little steps waiting for the stage manager's cue, my "fight or flight" instincts were powerfully active. I must admit the "flight" option had its appeal: "Just run away, out that door over there and onto 34th Street, and don't stop - they'll never catch you." But, with a supreme act of will, I decided to "fight" - go up there and ... face the music. I could only hope all my preparation would carry me through.

The path that led me to those four little steps had been a long and tangled one, and like so many stories, it started when I was a child. The music my father played on his prized hi-fi was big-band records by Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Glenn Miller, Tommy Dorsey (I would have heard Buddy Rich with the Dorsey band, or Harry James, way back then, without knowing it), Nat "King" Cole, Frank Sinatra, and other greats of that era.

At the age of eleven or twelve, my first inspiration to play drums came from the movie The Gene Krupa Story, so big-band music was deeply engrained in my memories, but, strangely, never in my drumming. In my teens I fell madly in love with rock music, and every day I practiced by playing along with the hits of the mid-'60s on the AM radio in my bedroom. When I started playing in local bands, together we discovered, and covered, the "underground" hits of the day: Jimi Hendrix, Cream, The Who, Moby Grape, King Crimson, Jethro Tull, Grateful Dead - all that adventurous, ambitious, and ardent rock music - and that became my music. That's what I listened to, and that's what I played, for the next - well, forty-three years and counting.

|

Final rehearsal |

In 1992, I had my first opportunity to play with a big band, when Cathy Rich, Buddy's daughter, invited me to play at a Buddy Rich Memorial Scholarship Concert in New York City. Though powerfully intimidated by the challenge, and naturally inclined to avoid it, I forced myself to accept. The results were ... let's say, "mixed." With too little time to actually rehearse with the band (a serious handicap!), it wasn't until we were onstage playing the first tune, "Mexicali Nose," that I discovered two things: I was too far away from the horns to hear them (as far as could be: they were upstage left; I was downstage right), and, second and far worse, the band was playing a different arrangement from the one I had learned!

That situation is usually the stuff of a performer's nightmares (musicians, stage actors, and professional athletes all seem to have them), but all of a sudden it was horribly real. Barely a minute into "Mexicali Nose," I went into what I knew as the first four-bar drum break, only to hear that the rest of the band - what I could hear of them - was still playing! Pushing away the panic, I just played steady time, holding it together while I strained to hear something in the arrangement that I recognized.

Though I survived that "train wreck," it's not the kind of psychic shock and trauma I am able to take lightly, or recover from easily. I played through the rest of the show, "Cotton Tail" and "One O'Clock Jump," and a drum solo, but I was shaken, and - it has to be admitted - wretched.

Later, I resolved that the only remedy for that bad feeling was to do it again, have another try, only this time under more controlled conditions: in the recording studio. In 1994, I produced and played on the Burning for Buddy tribute recordings, and that was a much more rewarding experience (as it remains - I still like listening to that music).

And yet ... I still had a nagging feeling that when I played in that style, I was just imitating it, not really feeling it properly. As the old Duke Ellington standard goes, "It don't mean a thing, if it ain't got that swing," and I didn't think I did.

So, in early 2007, when Cathy Rich and I began discussing another Buddy tribute concert (agreeing, "It's time"), I started thinking about trying to upgrade my "swing skills." That notion was reinforced by my old friend Jeff Berlin, a virtuoso bass player (perhaps the virtuoso bass player), in the kind of brutally honest advice only a really good friend - a really outspoken good friend - would offer.

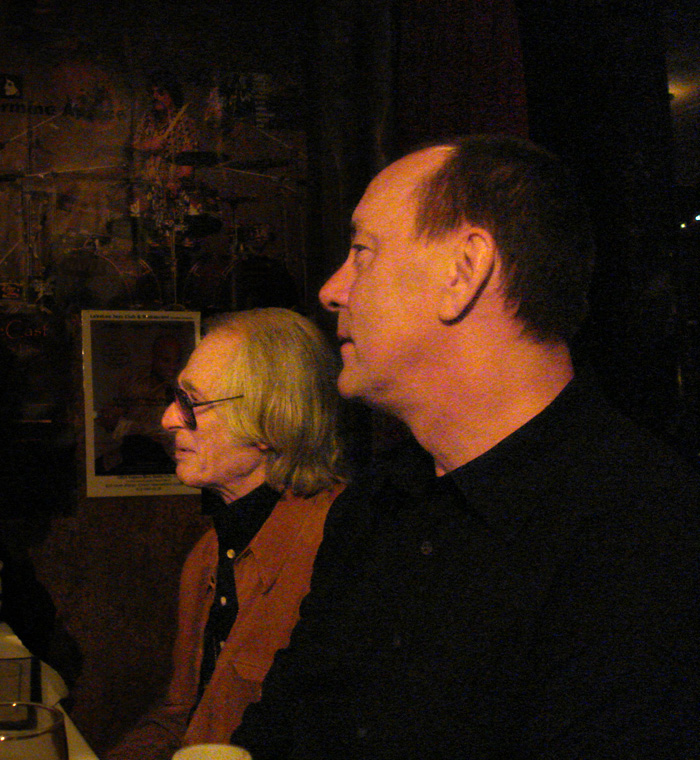

|

Jeff and me, final rehearsal |

Jeff and I, and my bandmates, have been friends for nearly thirty years, going back to Jeff's days with Bill Bruford's band. Since that time, Jeff and I have stayed in touch, however sporadically, and earlier this year, when Rush played in Orlando, Florida, near Jeff's home, I arranged to get together with him in the afternoon. When I told him I was going to be playing at the Buddy Rich tribute in October, he immediately offered to be my bass player. (Maybe "demanded" is more accurate - Jeff's the kind of guy who combines apparently boundless self-confidence with deep-seated neuroses and insecurity. I know many people like that - I see one in the mirror every day!)

Later, as Jeff and I exchanged e-mails about schedules and material, he offered a suggestion. Though phrased in more diplomatic language, the essence of what he said was, "Whyn't ya get some lessons, kid?"

And I said, "Oh yeah?"

And he said, "Yeah!"

And I said, "Oh yeah?"

And he said, "Yeah!"

So - it was on.

But seriously, the only real question for me was who. Jeff mentioned a couple of drummers he had worked with who he thought would be suitable teachers for me in the particular discipline of swing drumming. I consulted with my longtime teacher, Freddie Gruber, now 82-years-young, but pretty much retired from the "game," and another knowledgeable adviser, Don Lombardi, founder of Drum Workshop, and now spearheading an exciting online resource for drummers, Drum Channel (about which more later).

Now, here's a chain of happenstance that strains credibility. Back in the early '80s, I played on a couple of songs for a Jeff Berlin album, and in the Bay Area studio where we recorded, I met Steve Smith for the first time, as he was playing most of the other tracks on Jeff's album. A decade later, at that Buddy Rich tribute concert in '92, Steve also performed, and we met again for the Burning for Buddy sessions in '94.

|

Freddie and me, watching Joey play |

That's when I met Steve's teacher, Freddie Gruber, who became a hugely important musical influence and friend to me, and introduced me to the products of Drum Workshop (showing up at my house with one of their bass-drum pedals, to replace the antediluvian device he had frowned at on my practice kit - Freddie had also taught Don Lombardi, and been involved in the early years of DW). Earlier this year, at Freddie's 82nd birthday party in a nightclub in the Valley, where our friend Joey Heredia was playing, I met another former student of Freddie's, Peter Erskine. Peter had taught Steve Smith years ago, when they were both teenagers. What a web of connections.

Peter began his drumming career with the Stan Kenton big band, then went on to cement his reputation with perhaps the preeminent jazz group of the '70s and '80s, Weather Report. All along, Peter remained a teacher - for more than thirty years now, and he is currently Professor of Drumset Studies at the University of Southern California - and has continued to record and perform with a wide variety of artists, including Steely Dan, Chick Corea, Joni Mitchell, Diana Krall, various classical ensembles, and studio work ranging from big-band jazz to film scores.

All that - and the guy lived fifteen minutes from my house!

As the English would say, "S'obvious, innit?"

During a break in this summer's Snakes and Arrows tour, I scheduled a lesson with Peter. When I parked in front of his house in Santa Monica and walked up to the door, sticks in hand, I had to smile at myself. I was a thirteen-year-old beginner again, climbing the stairs to the Peninsula Conservatory of Music on St. Paul Street in St. Catharines, Ontario, for my Saturday morning lesson with my first teacher, Don George.

And of course, that's how I had to feel - there's no point in taking lessons if you're not going to surrender to the teacher. That's what I had done with Freddie back in '94 - followed his guidance to the extent of changing just about everything I had done before, in thirty years of playing:the way I held the sticks, the way I moved my hands and feet, the way I set up my drums, the way I sat at them - everything.

When Peter welcomed me into his backyard teaching studio, he told me he had watched my Anatomy of a Drum Solo DVD, and had appreciated it.

I said, "Hey, as far as I'm concerned, I'm a butcher, and you're a surgeon."

Peter laughed and spread his hands dismissively, "You're not a butcher."

I raised a hand up high, palm out, and smiled, "Hey - I'm a good butcher; I'd just like to get a little more surgery into it!"

So we began. The object of this course of study was to make me a better big-band drummer, but that proved to be a complicated assignment, and it started with the most basic element. Peter asked me to play slow quarter notes on the ride cymbal, just "ding, ding, ding," and I did, with a kind of circular flick of the wrist between each beat. That was part of what I had learned with Freddie - to think about what happens between the beats, and make it part of the music, a kind of rotary motion that makes your playing a dance.

But Peter pointed at that little flick of the wrist, and said, "What's that?"

Well, Peter had studied with Freddie too, so he knew what I was doing, and I was puzzled. I looked at him and said, "Um - timekeeping?"

Peter shook his head and put his fist to his chest, "Timekeeping is here. It's internal, and doesn't come from waving your hands in the air!"

He paused and raised a magisterial finger, "Own the time!"

So we started with that, working on remaking my ride stroke - again, the most basic of drumming techniques - with Peter offering visual metaphors like, "Pretend you're scolding your dog," with his index finger extended. "Your stick tip is a laser," with his fingers indicating the range of motion it should have - a thumb and forefinger apart.As I tried to replicate his instructions, I would slip into old habits, and Peter raised his finger in the dog-scolding gesture, and scolded me: "Quit waving!"

I laughed and tried again.

Thinking about it later, I came to understand that Peter's method didn't actually contradict Freddie's at all - it was simply a "higher evolution." Perhaps now I was ready to take that understanding of "the dance" and internalize it - make it part of my thinking, part of my feeling, part of my time-sense, but not part of my actual motion.

After that first three-hour lesson, which seemed to fly by, Peter gave me a printed list of exercises to work on, and a CD of music to listen to and play along with - but, he stressed, on high-hat only.

I drove home that day feeling dazed by this flood of information, and a little unsure. Could I do this? Devote myself to months of daily practice? Would it do me any good?

But I resolved to try. Because that's what I do - I'm a heck of a "tryer." I had warned Peter right away, "I'm a slow learner - but I'm stubborn!"

During the final run of the Snakes and Arrows tour in July, I started working on Peter's exercises in my pre-show warmup. When the tour was (finally!) over, I retreated to my Quebec house, where I set up a little practice corner in a spare room - just a throne, a high-hat, and a metronome (a lot more neighbor-friendly than a whole drumset, especially if you live on a lake in the woods). Every day I made time (in both senses) to keep working on Peter's economy-of-motion ride stroke, and exploring time and rhythm at different tempos. Then I would put on the headphones and tap along with one of Peter's "playalong" selections.

When I got back to California in early September, I scheduled another lesson with Peter, and the first thing he asked me to do was play a quarter-note ride on the high-hat. Peter watched me for a minute, then nodded and said, "Perfect." What a glow of satisfaction (and surprise!) I felt at that moment.

As an adolescent, when I worked Saturdays and holidays at my dad's farm equipment dealership, he would send me off to do something - polish a tractor, clean out parts bins - and when I finished, I would say, "Is that good enough?"

Without even looking at what I had done, Dad would say, "If it's perfect, it's good enough." So in my father's scale of values, my ride stroke was "good enough."

It's nice when hard work pays off.

Today, September 24, 2008, at precisely 4:32 p.m. Pacific Standard Time, for the first time in recorded history, I commenced to SWING!

It was as if I was looking down from a great height, for I watched my right hand ticking away on that high-hat, and it was OWNING THE TIME!

You know what I'm talkin' about!

Peter gave me some more exercises to work on, and I continued practicing every day. By then I had played nothing but high-hat for over two months (though I must say it never became tedious), and one day I sent Peter an e-mail, titled "Epiphany."

At my next lesson, Peter said he wanted me to play along with "Love for Sale," one of the Buddy Rich arrangements I would be performing at the upcoming tribute concert, on his drums - right now. ¡Jesu Christo! It would be the first time I had played an actual drumset in two months, and the first time I had ever played that song on a drumset. And not only was it in front of my master teacher, but he was going to record and film it ("for reference," he said).

I struggled through it as best I could (at least I knew the arrangement, if only on high-hat!), then had to stand aside and watch ruefully while Peter sat down and played it - properly. (I thought that was really unfair!) His playing was delicate, eloquent, and economical - a kind of artful, effortless surgery that expressed supreme musicality. I have written before that I believe the first deadly sin for humans might be envy, but right then it was hard not to feel a little of that poison.

|

Professor Erskine expounds for the cameras |

But fortunately, Peter teaches drumming with the same attitude my editor, Paul McCarthy, brings to my prose - an attitude I have described as "critical enthusiasm." Rather than telling you what you're doing wrong, they tell you what you're doing right - then suggest how you might do it better. That works for me.

The lesson pictured here was conducted for the cameras of Drum Channel, in their state-of-the-art multimedia studio in Oxnard, California. For nearly two years now, Don Lombardi has been developing and nurturing his "baby," building a team to create an online resource for drummers with unlimited horizons - a teaching forum, an archive of drumming history, a faculty of instructors impossible to match in any other medium, and an online "community center" for all those who worship at the Altar of the Drum.

Earlier this year, while I was preparing for the summer 2008 part of the Snakes and Arrows tour, I rehearsed in Drum Channel's studio for a couple of weeks, and in return for that opportunity to do my preparation at home instead of in Toronto, I filmed some instructional material for Don.

Drum Channel is a separate enterprise from the Drum Workshop factory, but is adjacent to it, so the number of prominent drummers who come through there is staggering - and exciting. Just while I was working there in April, and again for ten days in October before the Buddy Rich show, I encountered such an inspiring variety of great drummers, from artist-in-residence Terry Bozzio to old friends and new who were also contributing material for the Drum Channel: Gregg Bissonnette, Doane Perry, Joey Heredia, Chad Smith, Danny Seraphine, Alex Acuña (Peter's predecessor in Weather Report), Ralph Humphrey, and Steven Perkins. I saw bits of footage Don's team has shot of other drummers, and I can tell you, it's wonderful stuff - of the moment, and for the ages.

In early October, once again I traded some instructional filming for the use of Drum Channel's studio as a rehearsal space, the presence of my master drum tech, Lorne Wheaton, and the world's best commute - up the Pacific Coast Highway through Malibu to the farmlands of Ventura County, one day smelling of onions, another of cilantro.

Don and I thought it would be worthwhile to film a session of Peter teaching me - not only instructive in its substance, but also in its spirit, its message: after forty-three years of playing the drums, a guy like me could still try to learn something. (Jeff Berlin's advice to me applies to all musicians, really: "Whyn't ya get some lessons, kid!")

|

Jamming with "El Tejón" |

I also spent a day hanging and playing with my young friend Nick Rich, Buddy's grandson. I have known Nick since he was six, when we were both nervously awaiting the start of our first Buddy Rich Memorial Scholarship concert (that year, Nick's contribution was break dancing to Michael Jackson!). We "bonded" then, and kept that bond as he was growing up. Twenty-four now, decorated with all kinds of skin ink, body ornaments, and striped hair (I call him El Tejón, "The Badger" - he calls me "Uncle Noyle," after my grandfather's nickname for me, or - ha ha - "Grandpa"), Nick has become a fine drummer. He studied with the great Dave Weckl (another student of Freddie's), and has integrated some of Dave's fluid, intricate funk style with his own natural exuberance. Nick and I played "drum duets" for a while, and it was great to discover that our drumming interlocked as tightly as our characters always have. (I love that crazy mixed-up kid.)

This time Nick would be playing drums at his grandfather's tribute, and it meant a lot to him (he was only two-and-a-half when Buddy passed, in 1987). Nick was going to perform two of Buddy's more rock-oriented charts, "Beulah Witch" and, "Mercy, Mercy, Mercy" (originally a pop song by the Buckinghams, written by Joe Zawinul, founder of Weather Report - Peter told me that when he joined Weather Report, Joe gave him some "homework": the works of Nietzsche). That weekend Nick and I had a chance to rehearse our material with a real, live band, along with the other West Coast drummers in the show: Terry Bozzio and Chad Smith.

Don had suggested bringing in some music students from the nearby California State University at Northridge, where our bandleader, Matt Harris (Buddy's last keyboard player), taught. Matt had also written some special arrangements for Terry and Chad, while I had commissioned a big-band treatment of Rush's "YYZ" from one of Buddy's other longtime musicians and arrangers, John La Barbera. That arrangement had never been played before, so it would be a good opportunity to check it out, along with the chance to play through my other selections: Buddy's trademark arrangement of "Love for Sale" (a supreme challenge, but it was probably my favorite of all Buddy's vast repertoire, and I just had to try it - never mind that it had already been played so superbly not only by Buddy, but by Steve Gadd and Dave Weckl), "Time Will Tell," which had a good bass showcase for Jeff Berlin, and the traditional swing numbers, Duke Ellington's "Cotton Tail" and Count Basie's "One O'Clock Jump" (both of which had featured in my drum solos with Rush in past years).

For two days in mid-October, the Drum Channel studio was crammed with four drumsets and drummers, fifteen other musicians, an arsenal of video cameras, and a platoon of operators and engineers. It was a surreal scene, really, that perfectly exemplifies my title, "The Drums of October." Drums have never been a bigger part of my life than they were that month.

And the actual drums I played in October were pretty special, too. DW's restlessly innovative drum designer, John Good, imbued them with all his "Wood-Whisperer" magic, and they glittered in classic white marine pearl, like Buddy's, with gold-plated hardware for a little modern bling. My cymbal array was also completely redesigned for the performance - different ride, high-hats, and lighter Paragon crashes - with help from Chris Stankee in onsite testing, and, in the Sabian factory in New Brunswick, Mark Love, the cymbal alchemist ("literally," I told him, "turning base metals into gold").

Even the sticks I held in my trembling hands at the bottom of those four little steps were different. For this music, Peter had recommended something with a narrower shoulder and smaller bead than my usual "rock knockers," and out of a huge selection sent to me by Kevin Radomski at ProMark, I immediately gravitated to a pair of Joe Morello's signature models. They just felt "right" in my hands, and when striking and rebounding off the high-hat. (Coincidentally, that very day, in the car, I had listened to Joe's lovely playing on "Drumorello," on the first Burning for Buddy volume - and it had been sitting beside Joe in the studio while we recorded that, hearing him make those DW drums sing, that inspired me to try out their drums myself.)

Now, back to those four fateful steps. Short version: I climbed them. As quite a few of us in the show seemed to agree later, "It could have been better; it could have been worse." That, of course, is because we all apply my father's values: "If it's perfect, it's good enough."

For myself, once I was on that stage and behind the drums, I felt like I was in a kind of kinetic trance, my mind spinning in frantic orbits. At one point I remember watching my hands and feet play a certain figure correctly - all by themselves! That was proof enough that the hours of rehearsal and preparation had paid off. Generally, I just tried to play it safe and straight, not taking too many chances, and in the end ... it could have been worse.

Though I had watched all the rehearsals at Drum Channel and in New York, I didn't watch the actual show. I shut myself away in my dressing room and tried to escape the tension by reading a book (I know, weird, but it works for me, and I had chosen a perfect book - Case Histories, a gripping mystery by Kate Atkinson, whose genre is referred to as "literary thriller," which apparently doesn't have to be an oxymoron).

But my dressing room was right beside the stage, so of course I could hear every note of the show, and it clearly offered such a wonderful range of styles, in the drummers and the material - largely from Buddy's catalogue, plus some music specially commissioned for the event. As onstage host, it was Cathy's job to stitch the whole evening together (as she realized suddenly, with a little trepidation, just before the show), along with video clips of Buddy and us performers (as I stood twitching beside the stage while my long-winded video introduction played, I called over to the headsetted stage manager, Don Sidney, "Tell that guy to shut up!").

The audience was treated to a fantastic band, assembled by one of the featured drummers, Tommy Igoe (in a single word which I mean to convey much, Tommy's playing is "accomplished"), along with John Blackwell ("prodigious" - after watching John play at rehearsal, and talking with him a little about our lives - he told me Ghost Rider had helped him through a similar tragedy of his own, and the way he said it made my eyes prickle - I told him, describing his playing and his nature: "You're a monster - with a beautiful spirit," then added with a laugh, "and you can put that in your bio!"), Terry Bozzio ("inimitable" - the more time I spend in his company, the more I am inspired by his example of total creative dedication; and he was joined onstage by percussionist Efrain Toro, who can only be described as "delightful" - such a warm spirit in his playing and his demeanor), Chad Smith ("effervescent"), Nick (El Tejón) Rich ("formidable"), Donnie Marple ("promising" - the young winner of a drum solo contest), and a last-minute guest appearance by Peter Erskine ("masterly"). Peter happened to be in town recording, and when he told me he was going to be at the Buddy show, I made a wide-eyed grimace and said, "It's a good thing I work well under pressure!"

But Peter was very kind, and sought me out after the show to offer some encouraging words. While watching Peter play at rehearsal the day before, I had turned to a friend and said proudly, "That's my teacher!" When I told Peter about that, he aimed a thumb at me and said, "That's my student!"

|

"Facing the Music," onstage October 18, 2008 |

I gave him a big hug and said, "I'm not finished with you yet!" I already had the notion that I would want to continue studying with Peter, for I had learned one very big lesson: understanding more about jazz drumming is simply understanding more about drumming. That's got to be good - even in the "October" of my own years.

So, as Freddie would say at the end of telling a long story, "That's the way it went." I warned at the outset that this tale would be "long and tangled," but there was so much to tell. In such cases, I often think of the title of a novel by the Senegalese writer, Miriam Bâ, So Long a Letter, because it carried the same meaning.

Sure, it might have been better if I had taken time to write some of this between my previous report in August and now, but ... I was busy doing all that. It always seems that the more I have to write about, the less time I have to write it.

But I'm not complaining.

My life is not perfect, but it's good enough.