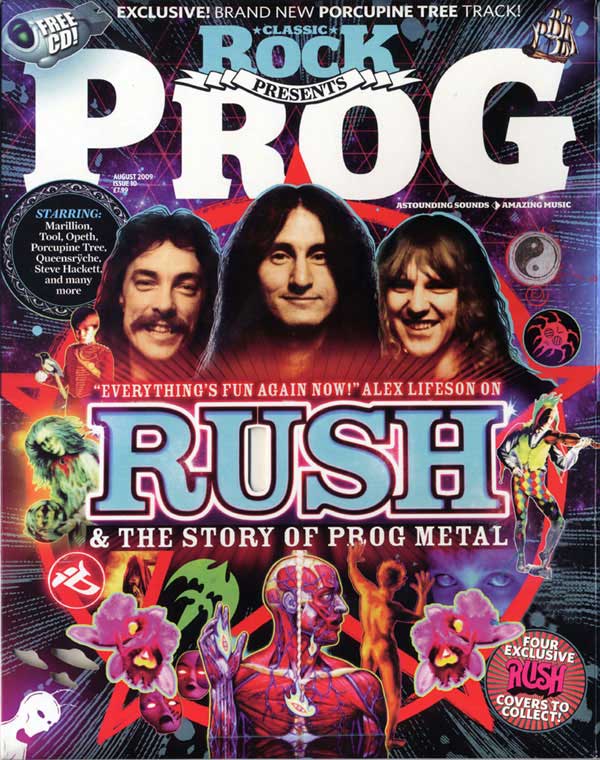

RUSH & The Story of Prog Metal

By Philip Wilding, Classic Rock Presents PROG, August 2009, transcribed by John Patuto

Making Waves

With roots as a modest jobbing rhythm and blues bar band in the 60s, by the 70s Rush had reinvented the progressive rock wheel and set the tech-metal bar for generations to come. In an exclusive interview for Prog, Alex Lifeson takes Philip Wilding on a journey of time and motion.

The next time you see Rush guitarist Alex Lifeson it'll either be as a cross-dressing cop or he'll be showing you how the extended and somewhat tricky guitar solo on Working Man is done via your home computer set-up. Times are tough all over, and even though Lifeson once made a name for himself in pan-stick make-up and a kimono promoting the band's 2112 album, who knew that it might come to this?

Alex is at home in Toronto and he's laughing, he laughs almost as much as Rush drummer Neil Peart smokes; that's quite a bit refreshed and relaxed after a friend's wedding in Barcelona and being off the road and out of the studio for almost a year, a year which, by all accounts, he's pretty much dedicated to playing golf and tennis. And teaching people to play the guitar.

"The Apple thing was fun", he says by way of explanation. "They have this new thing on the Garageband software [the mini-home studio affair that is part of Apple's iLife bundle] where songwriters and musicians teach people how to play their songs. It's great, you'll be able to download me. I went in and they filmed me for four days doing a song a day: Tom Sawyer, Limelight, The Spirit Of Radio and Working Man. It's really comprehensive stuff and you can slow it down to really watch what I'm doing.

"It was odd, you realise how difficult it is to play some of those solos slowly, especially on something like Working Man."

We imagine it's quite difficult to master at its normal pace.

"I guess," and there's another laugh, "I'm not sure how much time I spent on that solo originally, I didn't know better, I was a kid when I wrote that. But I loved doing the Garageband stuff, though, and the end result is just great. When you're learning to play with just notation it's not the same - what the right hand is doing is so important and you never get to see that stuff."

Rush began their career by spending six years as a bar band playing rock and roll and R'n'B (not the Usher kind). Their covers album, 2004's Feedback, pays testimony to the songs they grew up covering and then encoring with in places like the small Toronto neighbourhoods of Willowdale and Hamilton. Their self-titled debut of 1974 reflected that grounding too, although, famously, it saw original drummer John Rutsey's departure just as a disillusioned Neil Peart was returning from an unsuccessful spell in the UK where his dreams of playing music for a living were dashed, and he'd resolved to knuckle down and begin working for his father back in Canada.

"I think we'd decided that we were going to change musically even before Neil joined us", says Alex. "By the time it came to Fly By Night [1975] we'd been playing the other stuff for years, playing in bars and clubs and as you said Feedback was originally where we'd come from, those were the songs we learnt to play with, learnt to jam to. Of course, when Neil came in he had this music and all these lyrics and a whole new feel and approach to stuff and he wanted to expand our music too.

"Plus Ged and I felt like doing stuff that wasn't just hard rock, it was part of that whole learning curve, we knew that we wanted to do extended parts, suites if you will. We'd started going that way, even the sort of extended jam that was Working Man, but then on Fly By Night we experimented with By-Tor and the Snow Dog and is was starting to naturally move that way."

Fly by Night would garner them critical and commercial acclaim and, more importantly, help them begin (to) find their own voice. Also, in Neil, Geddy and Alex both suddenly had the lyricist they so desperately craved. For all its artistic aspirations and experimentation, Fly By Night was a relatively straightforward listen and was going over hugely well on their ever-expanding tours both as a headliner and as a support to bands like Kiss and Rory Gallagher. They'd now got into the grueling regime of touring for months at a time (if they had a night off as the support group, they'd book themselves into a club show as headliners) and then spending literally weeks writing and recording their next album. On their rare days off, they'd rent a hotel room, draw the curtains and watch cartoons all day, barely able to move. The hotel rooms would get bigger, but they wouldn't really learn to take a break until 1980's Permanent Waves LP. Neil Peart still recounts the story of recording the Hemispheres album at Rockfield in Wales - a session which they tagged a British tour onto as they were in the UK and their management thought it would be a good idea to get some more shows under their belts - and dragging himself out of the studio at 7am after working on his drum parts all night to discover a foggy Welsh morning and not have a clue what day it was.

"We were enjoying ourselves, I don't think we saw that kind of reaction coming," says Alex, a little ruefully.

Their third album, Caress Of Steel saw the band embracing their new artistic bent, complex, elongated pieces and a concept that sprawled over one side of the album was the order of the day. They sat back, delighted, the critics and their fans were less so. It couldn't match the reception or sales that greeted their previous effort, though it didn't bomb as badly as is sometimes made out.

"Our first real attempt of doing what we really wanted to was with Caress Of Steel, to an extent with The Necromancer, and then we did our first whole side of an album with The Fountain Of Lamneth. We really enjoyed the experience, we were very happy with it at the time. We were stretching out, trying new things, but then people don't always want new stuff, I guess. I know how people felt about it, but without making that album we'd have never have been able to make 2112.

"I remember it happening, just pouring out of us. Things seemed to be going that way, it seemed to go pretty easily for a first attempt now, but it's only 20 minutes, it'd be 80 now, imagine that? It would be intolerable. Nick [Raskulinecz - the producer of Snakes & Arrows] wanted us to do that, he was saying things like, just do one song, make it one song, but we talked him down. He's a great producer, he's got great ears and he was such a fan of our music, but one 80-minute song, no. Nick, no..."

Nick persuaded the band to revisit their musical past. As proud as the trio are of their catalogue they're determinedly forward-thinking. Rush aren't a band you'll see on a summer tour with other bands of their era churning out a set of hits and looking defeated when they play something new and the audience files out to find the bar or toilet. With Nick's help, Rush managed to look back yet still sound contemporary and vital. Suddenly, they'd made one of the best records of their career.

"Yeah, we brought back the Moog pedals for Snakes & Arrows, I resurrected the classic chord for the beginning of Far Cry, but was it a surprise to make one of our best albums in our 50s? Yes and no, it wasn't really a surprise, we went into make that album and we were so up about it," says Alex, "We worked on the songs at Ged's place and wrote everything acoustically again, the way we used to write albums like 2112. There was something genuinely special about it, plus add Nick's enthusiasm to all that and it was bound to be satisfying. But yeah, you're not meant to be doing some of your best work in your mid-50s."

"Plus we went back to being in a residential studio too [New York's Allaire Studios, in the Catskill Mountains], and that helps. But when I think about it, we could have been in a studio downtown and it wouldn't have mattered as we were so excited about it, we got caught up in the whole momentum. I suppose we did reinvent ourselves in a way, but all we did was revert to how we'd done things in the past; the acoustic songwriting. We'd let that approach drift a little, technology caught up with us and then overtook us a bit, so suddenly we had all these toys you can waste time with. Also, it's easy to dress a song up that way, you can't duck the point that a song's any good or not when it's just two acoustic guitars and Geddy and I are sitting opposite one other just feet apart..."

Not content with reverting to type musically, the band played an expansive US and European tour in 2007 and then as demand grew added another leg in 2008 to encompass parts of South America, Canada and anywhere they might have missed the first time around.

"The final leg of the last tour was when we caught up on parts of the US we'd missed, yeah," says Alex, "It was okay, but the problem was that we'd tried to condense the tour, we wanted everything finished before Labor Day [the first week of September], so we shoehorned in all these dates without too much space between them and we were just beat. You've seen us live; we don't do things by half. We played well I think, but it was something like between 40 and 50 shows and we're doing a three-hour-something show, but some of it was really great, we certainly got back in our groove again.

"Also, you know, getting to do songs like Entre Nous again, there was the demand to do stuff like that, the crowds really seemed to like hearing it, that makes everything fun again too. After we'd done the R30 tour and drew a line under things like Closer To The Heart, it was good to look at different parts of our catalogue and experiment with some of the less well-known material, the stuff that we haven't aired for years. I know Ged was knocked out when he went back to listen to Permanent Waves and it was so much fun to rearrange those songs in the way we did, I hope we get to do a lot more of that, to tinker a little with some of those old songs when we play them again."

For Neil and Geddy the lowest ebb of their time with Rush was around the recording and touring of Hemispheres (1978). As Peart remarked: "Geddy and I have often discussed probably the lowest part of our whole lives, with other exceptions in my case [Peart lost his daughter and wife in the space of 10 months] and that was the Hemispheres era, just feeling so bad and so drained." For Alex, the nadir came later, after another epic tour had almost done for them.

"Post-Hold Your Fire was the lowest ebb for me," he says. "I don't think I'd ever consciously thought of leaving the band, but I was feeling a bit lost, we'd just been through Europe and the UK and then we'd come back from Britain and I think we'd recorded the show in Manchester and we had a week off after what had been a very long tour and then it was back into the studio for the mixing of Show Of Hands [live DVD, 1989].

"The three of us were sitting there at the back of the mixing room with these black circles under our eyes, barely speaking to each other at that point and then I remember we were talking about taking seven months off for the first time ever. Thinking back on it now, we were selling ourselves short! But it was clear to all three of us I think that if we didn't take that break then that we'd have to stop, we were completely exhausted. It was a very rigorous tour, very long and it was when we were using a lot of new technology on stage too. Geddy was really tied to his stuff, singing, playing, the pedals, the keyboards, he had to focus very hard all set, we all did. That's still a real issue when we plan sets now, Ged doesn't want to be tied to one place on stage, he needs to roam!"

Ultimately, of course, the band was forced to take an extended hiatus in 1997 when Neil's daughter was killed in a car accident and his wife died from cancer less than a year later. Neil - a man who plays the drums every day of the year, though will allow himself Christmas Day off- put down his drumsticks and didn't really pick them back up again for two years.

"I'm not sure what kind of band we would have been if we hadn't taken that time off, who can tell?" says Alex, "It was four years and we certainly didn't stop, I produced and did TV stuff, it was just that playing in Rush at that point wasn't an option. Then when we did reconvene for Vapor Trails and it became this most emotional and powerful record. We think very highly of that record, but there are things wrong with it, the way it sounds, it could have been better recorded, we would have done things in a different way, but I suppose we weren't thinking straight, no, not that, it was just very raw, very visceral, you know."

Normally very effusive, Lifeson struggles with the words momentarily: "A lot of that stuff on there is first takes and demos, but because of what had happened and how we felt, we didn't want to re-record, they felt too precious in a way, we were very protective of those songs at that time, we were all feeling very tender about it. Rich [Chycki] - my engineer - re-remixed One Little Victory and Earthshine for Retrospective III and they sounded just great."

"I'm not a big fan of those compilations to be honest, they come and go, they're contractual obligation things, but we'd all been feeling the same way about the sound of Vapor Trails and we've talked about revising the sound, we've talked about it a lot, I guess enough time's passed now, I think we're more curious than anything to see how it would sound. Now having heard what Rich has done with some of those songs too, it's really made us think about it a lot more. He did a great job, he and I actually share a studio now, that's where he did the work, it's a place I have in town, I'd been away and when I came back he'd ripped all of my gear out, he apologised when he saw the look on my face, I thought I'd walked into the wrong building, but what a great mix room we have now."

Even though it's only July, Lifeson's thoughts are already turning to the autumn and starting work again. A few weeks before we talked he's got up on stage with The Tragically Hip at one of their shows in Toronto and encored with them ("We were playing golf together and they invited me down, I love playing at other people's shows like that, no responsibilities! Well, only to the band in question..."). Whereas Geddy can put his bass to one side and not look at it for months on end, Lifeson, like Peart is, you feel, someone who can't leave his guitar alone. Though, that doesn't stop him enjoying his time in the sun.

"I'm feeling good, I'm enthusiastic to get going again," he says. "We've been traveling, playing tennis and golf and in the nicest way it's been great not to think about the band for a while, because whether it's mixing the live stuff for DVD or dealing with the catalogue then there's almost always something. We came off the last album and decided that we'd have a year away from it all, but that was after last summer and now the fall's coming, it'll be here before we know it.

"Tentatively, we start work on the next album in the fall - I did mention it to Ged before he went away on holiday and he sort of looked the other way. Come September and we'll certainly have some plans, we did the last record, or we started on the last album in the fall and I'd like to do that again, start recording maybe. I don't know who might produce, that's some ways off yet."

And when not strolling or teeing off along the greens or enjoying the 2009 Wimbledon final - he's a huge tennis fan, he once realised his dream to play at Queen's Club in West London and promptly put his back out on the court - he's been exercising his acting muscle. For those who don't know them, The Trailer Park Boys is a cult comedy show in the US and Canada. Think South Park with actors and possibly a little more subversion - they're also Rush fetishists. The band appeared on their first movie soundtrack, shows are named after Rush songs and Alex has appeared in the show more than once. Even bound and gagged, he's a natural.

"There's been more acting. I did a small part in a movie called Suck, it's a vampire film, Moby, Alice Cooper, Henry Rollins and Iggy Pop are in there too, it's a Canadian director and it looks great, I play a border guard," he says, warming to the subject. "I'm also in the second ... Trailer Park Boy's film, I really enjoy working with those guys, they hand-picked the part for me, I'm usually in some kind of uniform, this time I get to play a cross-dressing cop, how hard can it be?"

And he's still laughing as the phone line goes dead.

Why do I love Rush?

"Because RUSH WERE COOL!" says producer/songwiter Jason Perry.

"There are some things that you just cant put your finger on. Life's great enigmas... Why anyone would love Rush is one of em.

I properly love Rush and I'm not the only one. Much has been written about musicianship and Peart's lyrics but how many dare admit that in the 80s and early 90s RUSH WERE COOL! I'm totally serious.

My name's Jason and I'm a record producer. Before that I was, and am about to be once again, the singer in a band called A. We had a song called Rush Song and before we were called A we were called Grand Designs. Ahem...

The first record I bought was So Lonely by The Police and the first gig I saw was The Jam when was 12. All good then. Until I heard TOM FUCKING SAWYER!! Shit the bed!

I moved from Leeds to a village in Suffolk where all the village metallers were into Dio and Saxon and Maiden. Nothing wrong with that, but I dressed like a mod. I didn't fit in. I loved The Police and U2 and Big Country but I also loved Van Halen and Maiden. I wanted to like rock music and get a normal girlfriend at the same time!

Rush to the rescue. There was a picture of Atex Lifeson in Kerrang! wearing a cool black and white T-shirt under a white suit jacket playing a red Strat. He had white hair with this awesome Duran Duran-style fringe. He could have been in The Police or Japan but he was in a rock band. It was the Signals into Grace Under Pressure era and the fashions were not a million miles from what your average rock/emo kid wears now. I really thought that 80s Rush were the coolest band in the world. I had the Grace Under Pressure live video to prove it and I wore the tape out. Geddy was playing synths and Neil was playing Simmons drums and they had lasers and back screen projections, All the crowd had short hair and looked like Tony Hawk and they were all air drumming to The Spirit of Radio. Rush were, and still are, a refreshing diversion from anything else that's going on in the rock world. I think that's one of the main reasons why I loved 'em and will always love 'em. They never really fitted in. They looked like they'd fallen into the pages of Kerrang! by mistake and they seemed a million miles away from all the bluster and excess of all those other bands. I've always been that way too and I've often felt like a square peg in rock's round hole.

There's a feeling inside when you love Rush. Like you're the only one and you feei like you've found this amazing cool secret, it must be how Jehovah's Witnesses feel and to be honest I've often felt like knocking on a few doors myself and spreading the word. But then you go to Wembley for three nights of sold-out shows and realise that you're not alone and that you're not special and that there's plenty more Rush geeks out there. Hey, I even saw a girl once! Cool.

Then there's the music...

Everything I know about music comes from air drumming to Rush. Feeling every skip and every late 'down-beat'. Those endings. In A we used to milk our endings - I remember DJ Chris Moyles going off on Radio One for about five minutes about our endings. We had a song called Champions of Endings which was about the end of Limelight. I love the way that Alex rarely plays chords, he chugs and punctuates and adds colour, just like Andy Summers or The Edge or Pete Buck. I love the way Geddy and Neil play together and how there's always movement. When Rush are at their peak, they move and swell and change gears effortlessly. They can be emotional too, like when the synths come in during YYZ, that fat 80s synth sound and those glass smashes. Makes you feel like you've just had that first kiss."

Rush: The Movie

Fresh from their success with IRON MAIDEN's Flight 666, filmmakers Sam Dunn and Scot McFadyen turn their attention to Rush.

It seems fitting that the two men who have managed to present rock music in a well-structured and thought-out light cinematically in recent years should turn their attention to Rush. That's exactly what fellow Canadians Sam Dunn and Scot McFadyen are now doing, with the first ever feature film documentary on Geddy, Alex and Neil.

"Geddy had been in Metal: A Headbanger's Journey and we were thinking about other bands we could work with," explains McFadyen. "We felt that Rush had always been overlooked by the critics so we met them on tour and they liked what we said. We started working on it, then Iron Maiden came about so we took a break to do that and raised the financing for the Rush film. We've started on it now and done a load of interviews so now we're editing with a load of archival footage.

We've been lucky, not only have we had access to [Rush management] SRO's archives but also Geddy, Alex and Neil's own personal archives," enthuses director Dunn. "I was just at Geddy's house this week. Going through his personal collection of memorabilia. I dug up some gems I don't think Rush fans have ever seen so we're hoping to offer something new."

As Rush fans themselves, Dunn admits this is making him feel like a kid let loose in a candy store.

"Well, Geddy's definitely the premier band archivist. He has a massive collection of photographs and clippings. We even got our hands on Neil's handwritten lyric sheets from back when they were making Fly By Night, 2112 and A Farewell To Kings, and I don't think they've ever been seen before."

Given the private nature of the band, particularly drummer Neil Peart, the fact that the band are fully co-operating with the filmmakers makes the prospect of the finished cut even more mouth-watering.

"Well they're not quite at the end of their career - they have a few albums left in them," states McFadyen. "They're going to start recording their next album soon and we're hoping to be able to show that in the film. They seem to like the scope of what we were doing. We were going to take the time and energy and talk to hundreds of people. We were hoping for the ending to have them to be inducted into the Rock 'n' Roll Hall Of Fame. So we're kind of holding off to see if that might happen, because if any band deserves it it's them.

And as for the reclusive Peart?

"Neil's very private but that's understandable given everything that he's gone through," muses Dunn. "But what we found was that when you get Neil on a motorbike in a remote area, the kid comes out in him. So we have filmed Neil riding through Quebec, parts of Europe and California and we've found that when you sit down with Neil, one on one, he loves to talk. And Rush fans know that he's smart and articulate and always has something interesting to say."

The as-yet untitled film will also feature contributions from a host of musicians who have toured with or been inspired by Rush, including Billy Corgan, Trent Reznor, Tool, Foo Fighters, Kiss, Uriah Heep and Primus. Dunn and McMadyen look to complete filming at the end of this year, so a theatrical release is slated for early next summer.

Watch out for exclusive footage of the three members interacting with each other in the band's unique way.

"We got some rare backstage footage in Europe," Says Dunn. "And the camaraderie between the three really comes across. They're almost telepathic and I think that's what's been behind their great success. They have such a deep understanding of each other's personalities and of each other's strengths. That's something that's pretty amazing to see and what we want to convey in the film."