Neil Peart's News, Weather and Sports

Adventures in the Wild West

NeilPeart.net, December 14, 2012

We began the third leg of the Clockwork Angels tour, in mid-November, 2012, with a computer crash. Such a mundane event fostering an adventure would have seemed unlikely to me, but perhaps not to Michael. I am sure he has those kind of techno-geek dreams all the time. ("I was reformating a hard drive and writing code for a killer app - when suddenly I opened a portal in the space-time continuum!")

After an all-too-brief break at home, Michael and I flew to Portland, and Dave picked us up with the bus and trailer. He drove us north toward the first show, in Seattle, but following my request, parked us south of there, in Chehalis, for the night. I planned a short "warm-up" ride for the show day, and in the morning Michael and I unloaded the bikes and set out into the inevitable rain.

Later that day, on the bus outside the old arena in Seattle, I looked over the paper maps of Southern Oregon and Northern California. I needed to work out a route to the next show, in San Jose, but knew that, unfortunately, I would have to stay away from the higher mountains, like the Cascades and Sierras. They would already be snow-covered. So, sticking near the coast, I highlighted some tiny roads through Oregon and into California, including one I remembered traveling with Brutus back in 1996. When I told Michael about that, he acted all incredulous - shaking his head and saying, "How can you remember that?"

The only reply ought to be, "How could I forget?"

Certain roads etch themselves into my mind like a good song, and are remembered the same way - the melody, background, cadence, changes, and overall mood. It is also similar to how I might remember a person once encountered - how they looked, how they behaved, and how we - "got along."

Also, one settlement on that Northern California backroad was called Happy Camp, and that would tend to stick in one's memory. (Who wouldn't want to go to Happy Camp?) But more than that - I recalled how the road followed a river (the Klamath) in long uninterrupted stretches of fast, sweeping bends. I would be glad to revisit such a road, especially in the opposite direction (for every road is really two roads - maybe more, if you add in weather and seasons). From there, I thought we would work our way over to the Pacific coast at Cape Mendocino ("The Lost Coast"), and maybe down to the town of Mendocino for the night. (I always have to put that "maybe" in any riding plans, and this day would be a prime example of why. My all-time favorite church sign: "Want to make God laugh? Tell him your plans!")

After Michael translated that route from my paper map to his computer's navigation program, Mother, he tried to copy it to our onboard units, Doofus and Dingus. It was an operation that he typically did every show day, but this time, it just wouldn't work. Time after time, the cyber-minds failed to communicate. Michael is a trained computer forensics investigator, and he eventually determined that the problem was in his machine. It wasn't a conventional catastrophic crash, a sudden collapse into chaos (what a flight of accidental alliteration - there goes another one!), but a more gradual loss of its faculties - like Hal in 2001: A Space Odyssey. (And it would soon be singing the equivalent of "Daisy Bell" - "On a bicycle built for two.")

(A good story hangs on that reference, for techno-geeks. It was the first song sung by a computer, in 1961.)

Later that day, or night, after many attempts at patches and fixes, Michael thought he had found a work-around. He copied the outline of the route, like a digital stencil, and pasted it onto the maps in Doofus and Dingus. The route and the map were joined at last, but we would learn that they interpreted that design very loosely.

Early the following morning, cool and misty, we set out from a Walmart parking lot in Grants Pass, Oregon. The paper map showed a tiny gray line leading down into Northern California, and although it was marked as paved, I wasn't too alarmed to find us on a gravel road, winding through deep conifers. But as Doofus and Dingus kept making turns onto ever-smaller routes, mere gravel tracks and abandoned logging roads, I began to wonder. I tried to keep an eye on the compass, to make sure we were tending south. Then I began to see patches of snow here and there, and started worrying.

Further episodes in this story will show that we can get through most obstacles - eventually - but not deep snow. Still "the Boys" kept leading us onward, the purple lines on our screens turning this way and that. It seemed like they were just plotting a more-or-less random route, with Michael's applied "stencil" serving as a rough guide to its shape and direction. The riding wasn't unpleasant, but its aim was worrisome, and when I eventually saw a small brown-and-white sign, a marker for a National Forest road, with a number, I felt a sense of relief. "At least we're on a road that has a number." By that point, after rambling through endless evergreens on logging roads with no sign of recent tire tracks, it seemed like civilization.

Then came the "false dawn" of a glimpse of paved road. It might have been the one we were supposed to be on the whole time - though at least two hours earlier, without all that meandering around the rainforest - and it led in the proper direction, toward the southwest. The problem was that it took us higher, and more snow was appearing. Eventually, as shown in the opening photograph, we were threading narrow lines of pavement between streaks of packed snow and ice. Worse was the fear, after previous episodes in Oregon, New Mexico, and Washington State, that we could soon be marooned in a snowpack.

This time the fates were with us, and the road turned downhill, away from the snow, and we emerged just where we (and our route) had hoped to be: Happy Camp, California. As I had remembered from fifteen years ago, the road from there along the Klamath River was a winding delight. After forty miles of that, we paused at the roadside for a break, and Michael declared it his favorite ride of the tour.

However, technology wasn't finished messing with us yet. The transplanted route-map worked fine once we were back on major roads, and we made our way over to the main highway, California 101, and a few miles south to the turnoff for Cape Mendocino - the Lost Coast. Brutus and I had explored that area back in 1996, on the Test for Echo tour, and I had passed through on my Ghost Rider travels, in 1998. A few years later I returned by car, taking a long scenic route home from a track day at Thunderhill in my Aston Martin DB9.

|

The Lost Coast |

The road around Cape Mendocino is a narrow, twisting strip of pavement (sometimes quite "technical," for riding or driving) that leads from the picturesque Victorian town of Ferndale through dense, mossy woods out to a grand vista of the blue Pacific. This was Michael's first visit to the area, and later he told me he had been dazzled to emerge from the dim forest to this fantastic expanse of sea and sky.

When we turned inland again, my route was to take us through the giant redwoods of Humboldt State Park, then down through the big trees on a scenic route called Avenue of the Giants. However, the Boys had other ideas, and led us away from all that, southward into a complicated network of narrow paved roads, little more than one lane wide, twisting through forested hills. The going was slow and difficult, and I was pretty sure those roads had not been on my highlighted route.

The air was often fragrant with the slightly skunky perfume of growing marijuana, as we were in a remote part of Humboldt County, famous for growing California's medicinal (and recreational) weed. Passing through one remnant grove of redwoods (so few of the big trees were left after the wholesale logging of the 19th and early 20th centuries that each grove has a name), we were suddenly in a dark twilight, our headlights a pale spray on the pavement.

By the time we emerged at the main road again, the light everywhere was fading into evening, and it was time for a rethink. I knew that if we continued on to Mendocino, we would face a two-hour ride along a dark coast, on a tortuous little road, with fog another possible hazard. (To quote Michael from a previous story, "It's not safe, it's not smart, and it's not fun.")

Pausing at the intersection (always wanting to be safe, smart, and fun), I went through the buttons on Dingus to scan the list of local lodgings, and saw there was a Best Western just two miles away. I decided we would take shelter there, and revise our plans for the following day. Finding ourselves in Garberville, California, willy-nilly, we decided we liked it fine. With our bikes parked in front of our rooms at the classic Best Western, we unpacked and enjoyed our post-ride plastic cups of Macallan. I made up a little song for Michael:

"Get up early, and ride all day

But when it gets dark, find a place to stay."

He just sniffed, but I'm sure he thought it was a pretty good song. I'll bet he was singing it in his helmet for days...

The town offered a selection of motels and restaurants (including a Chinese one with the groan-worthy name of "Cadillac Wok"). Michael and I strolled a few blocks to a New Orleans-style place, and noticed the local "plantocracy" all around. Young people in a variety of hairstyles from dreadlocks to "man-buns" wore colorful clothes that appeared homespun. One guy's outfit I could only describe as "snowboarding pants made by an Incan grandmother." Another young man in blond dreads wore a hoodie decorated with a Grateful Dead album cover. They all looked prosperous, but freaky, and we decided that Garberville was definitely "Growerville."

Next morning I led Michael on a backtrack north through part of the Avenue of the Giants, so he could see the majestic redwoods for himself. He thought he had seen them before, on a ride in the Sierras, but I informed him that those had been sequoias - a related species that can also grow to be thousands of years old. The sequoias are actually larger in girth, but the coastal redwoods are taller (the world's tallest tree is a redwood, at almost 380 feet).

With a sarcastic tone, Michael said, "How did I manage to live so long without needing to know things like that?"

I snapped back, "There's obviously so much you've managed to stumble past without thinking you needed to know. Pretty sad, really."

He said a bad word.

(Michael says a lot of bad words.)

But you know, it occurs to me that an episode like that might be a good example of why Michael and I get along pretty well - despite traveling together day after day, night after night, and mile after mile. (Ten years now, and something over 100,000 miles.) Our attitude toward each other tends to be constantly nasty, but in a funny way. In contrast, as the 2012 part of the Clockwork Angels tour was grinding to an end, after three months, we had both noticed an atmosphere of tension around the work-days. With sixty-five people living and working together in tight quarters in our traveling circus (carried this time by six buses and nine trucks), sometimes individuals get weary, tempers fray, patience fails, and there are altercations. The daily good humor and morale-raising jokes continued (for example, we and our audiences would often be surprised by costumed characters capering about during the shows). But during the day, I would catch the backstage gossip, and hear about certain crew members or drivers getting into verbal scraps. After many (many) tours, you learn that it always seems to happen like that toward the end.

Between Michael and me, the escape from that is that we talk so awful to each other all the time that nothing has to be held back - no tension or resentments build up inside. Petty issues are spewed out in a constant stream of gay banter, acid remarks, vicious insults, and gutter profanity that doesn't allow any grudges or annoyances to linger. It's like a pressure-release valve that's always on, just a little. Or a lot.

Michael still laughs over my comment from a few tours ago, "I love that you feel you can talk to me like that - but I really wish you wouldn't."

|

Mojave Joshua Trees |

Many relationships might benefit from such "loose tongues."

After a week of working "from home," commuting to shows in Southern California by car (those freeways are no fun on a motorcycle), we were on the bikes once again, riding out early across the Mojave Desert to Vegas. On previous tours we always seemed to do that ride in mid-summer, with the temperature well over a hundred, so it was pleasant to experience that well-loved landscape in cool weather. The next day, though, the desert would not be so gentle with us.

After the Vegas show, Dave drove us to a truckstop in Kingman, Arizona. Michael's computer had been replaced by then, and Mother and the Boys were once more playing nice together. After unloading the bikes in the morning, we followed my chosen route down through Western Arizona, on long stretches shown on the map as unpaved. We call those the "mystery roads," because we truly never know what we're going to get. On the previous tour I had chosen a road just east of this one - up through the Vulture Mountains toward Prescott - that was shown on the map with the same dotted line, and it turned out to be a nice paved two-lane through undulating cactus desert.

This one started out as graded gravel, through the middle of what we would come to know is called the Arizona Outback.

And we would come to know why...

At this point, I stopped and straddled the bike and waited for Michael - hanging well back out of my dust. (For that reason, a crosswind is welcome when riding in the dirt.) I put on my four-way flashers and held up my hand - the understood signal for a photo stop - and asked him to photograph me riding through this background. Because, I told him, "It's the only place in the world where you will see both saguaro cactus and Joshua trees. And I believe the Arizona Joshuas are a slightly different species from the California ones."

He shook his head and repeated, in a weary, acid tone, "I don't know how I've managed to live all this time without needing to know that."

I suggested he perform an anatomically impossible act.

The signs that welcomed us to a couple of long stretches of gravel, and an eventual rather desperate plight, were only mildly daunting. Most of the time, these "primitive roads" were decently graded gravel, and the riding was fairly easy, through vast, rugged panoramas of saguaro, mesquite, and Joshua trees. After thirty or forty miles we came out to pavement again, and paused for gas around Wickieup. From there we turned west once more, into the Outback, on Chicken Springs Road. (You pretty much know a road with a name like that is going to lead you into desert desolation.) For a couple of hours everything was fine, more graded gravel and fetching cactus desert scenery. The temperature climbed into the eighties - the first time we had been truly warm on the bikes for about two months - and it felt just fine while we were moving.

It was November 24, 2012 - the Saturday of Thanksgiving weekend - so there were more people about than we would usually encounter on such a remote track. Ahead of us, long clouds of dust announced the approach of small all-terrain vehicles, "quads," and we kept well right on the track to avoid them - or let them avoid us.

At one crossroads, Doofus and Dingus pointed us forward, but a large yellow sign announced, "No Through Road." A few big pickups with flatbed trailers were parked in a clearing, and people were loading and unloading their quads. One had a shotgun mounted across his handlebar, and I asked its rider what he was hunting. "Quail," he said.

I pointed up to the "No Through Road" sign, and told him we were trying to make our way to Alamo Lake, then south to Wenden. My paper map and the GPS said the roads connected. He nodded, seemingly knowingly, and said offhandedly, "Oh, you can make your way around."

Those words would come to haunt us, as we discovered what it meant to "make your way around" that lake.

Alamo Lake is a reservoir on the Bill Williams River, and its deep blue expanse came into view among the folds of green-dotted brown hills ahead of us. Somewhere across that lake was the road we needed to get to - to get gas, to get water, to get anywhere.

The road continued to be fairly firm gravel, with only a few deeper stretches where our wheels sank in and threated to "upset" us. Those tended to be in the lower dips - so-called washes - where flash floods leave loose debris that is later simply graded over. Sometimes we had our feet down as outriggers, ready for a dab to steady our balance, but there was nothing too dramatic. Just a normal "primitive road." However, as we neared the lake, that road became something less than primitive - either unborn, or long dead. We circled around a few small, rough tracks that meandered into dead ends, and it truly seemed to be a "no through road" situation, despite what the hunter had said. Trying one last loop, we encountered a couple sitting in their quad, and I pulled up beside them.

With a self-deprecating smile, I asked, "Do you know where you are?"

The woman laughed and nodded, and when I explained our situation and our quest, she said that one of the tracks looked like a dead end, but wasn't. She said they were headed back that way to their camp across the lake, and we could follow them if we liked. The man said there was some silt - "like talcum powder," the woman added - and a stretch of sand, but they seemed to think we could manage it.

It is a truism of adventure travel that when things get really bad, you seldom stop to take photographs - you're busy trying to survive, and nothing seems more important than to keep moving forward. The trail they led us down was narrow and very rough, just wide enough for a quad to negotiate, with tight, winding switchbacks up and down through close-set ravines. The surface was rutted, eroded, and studded with rocks of all sizes and troughs of sandy gravel - fine for an all-wheel-drive quad, but more difficult for heavy motorcycles. As my bike bucked under me, and I fought for control over boulders and skidding in gravel, I was thinking, "I am going to get hurt." I knew I was going to fall over, it was only a question of when - and there were so many hard things to land on.

Michael got stuck first, his rear wheel spinning into gravel and sand on an uphill hairpin. I parked my bike and walked back around the corner to help. His rear wheel was buried so deep that the best fix was to lay the bike right over on its side, slide it sideways a bit, then stand it up on firmer ground. We set off again, but minutes later, I was down. However, the bike lay against a rut that kept it upright enough for me to raise it myself. Then, trying to tiptoe down a steep, narrow, rutted incline, I went over hard, jumping clear as the bike landed far down on its side. Switching off the engine, I said some bad words. Another group of quad riders was waiting at the bottom for me to get out of the way, and a couple of them helped me get the bike upright again.

The next time it went down, and we got it up and started again, a middle-aged guy with a Harley T-shirt said, "If my bike fell over that many times, it would never start again." By then I had lost count of how many times we had been over. Several times I got mired in deep, loose gravel, and smelled burning clutch as I tried to power out. This was all getting a bit ...serious.

Finally we reached the "landmark" the first couple had told us about - the rusted carcass of an old-style, rounded school bus, about half of it buried under sand and gravel. (Perhaps a clue to a flood that had destroyed what used to be a road around there?) We had made it through the silt, a few inches of light powder over a hard surface, so not too bad. But now came the sand, and the other quad riders gave us the impression there was quite a stretch of it.

The exertion and the high-eighties temperature were getting to Michael, who does not tolerate heat well. He rested in the shade, grateful for a bottle of water and a can of Sprite offered by our "guides," Stephen and Karen. (I was carrying a little water, but Michael was not. I had asked him back at Wikieup, just before we turned onto Chicken Springs Road, with a store across the road, if he wanted to stop. He had said, "No - I'm all right." Now he wasn't. Some kids never learn...)

I rode ahead to have a recon of what was ahead of us. Almost immediately I bumped down a steep bank into a deep expanse of sand. Down went the bike, and with it my heart. I saw that the expanse of bare, rippled sand stretched ahead a long way, and we were never going to make it across that. Yet going back was out of the question. We were getting low on gas, and even the spare gallon on my bike's rear rack might not be enough.

And then, out of nowhere - a miracle of humanity occurred. All of those quad drivers gathered around to help us. Three couples, in their fifties, spent a good two hours of their holiday afternoon to help these two stranded motorcyclists.

One couple had their dog with them on their quad, a black spaniel named Mandy, and I joked that I was going to remember this rescue as "Operation Mandy." The man called John brought over a length of heavy yellow rope - saying that his friends always kidded him about carrying it - and we tied it around the forks of Michael's bike. Tom, with the Harley shirt, and I held it upright while his wife, Cathy, pulled with the quad. It was still tough going, just keeping the bike on its wheels in that deep sand. Holding onto the handlebar and the luggage case, my boots scrabbling for traction, I was leaning so hard into it that it felt like I was supporting most of its weight. After a while I said to Tom, "I'm about to lose it." He said, "Me too," and called ahead for his wife to stop. (I liked how he always called her "Baby.")

|

Operation Mandy 2.0 |

Behind us, another strategy was being attempted. Michael, Stephen, and John lifted the front wheel of my bike into the rear box of Stephen and Karen's larger quad, and that proved to be the best solution. Michael and Stephen crouched in the back to steady the bike, while Karen pulled slowly along. Their little caravan soon caught up to our noble but less effective effort, and a group decision seemed to favor waiting for the larger quad to get my bike to "solid gravel," then come back for Michael's. Tom and I were left alone with Michael's bike, and things were quiet for a long time. We stood beside the stranded motorcycle in the shade of cottonwoods, tamarisk, and dwarf willow in the dry river bed. This belt of green looked better watered than the surrounding desert, and I felt a distinct coolness seeping from them. I asked Tom if the river flowed underground in that area, as desert rivers sometimes do, and he said he thought it did.

Tom and I made some small talk - he had lived in Arizona for over thirty years, because his wife was from there, and I told him that was why I lived in California, too. He scouted ahead a short distance, and thought the next stretch of the trail looked firmer - perhaps if we pushed the bike that far, it would be ridable. I said, "I like the way you think," and he replied, "I'm not the kind to just stand around and wait." I said, "Yeah - I'm that way too. I'll try pushing while you ride, if you like."

It seemed right that I, as one of the "strandees," should do the heavy work, while my rescuer should ride - if he could, anyway. And it turned out that Tom's Harley T-shirt represented a real rider (not always the case, as even non-riders probably know). Just by the motion of his left hand on the clutch lever - smooth and easy - I could tell he was good. He sat astride the bike and got the rear wheel spinning, while I leaned into the rear rack and started pushing. Dust and sand sprayed up over me, but it worked. Our progress was slow, but steady, and when we reached the firmer area, Tom rode a long distance. I followed on foot - happy just to be moving forward. Eventually Tom got mired in soft sand again, and when I caught up with him I pushed for another stretch, until we reached a worse obstacle - a steep, rutted bank of sand up to higher ground. John came along in his little quad, and directed his wife, Pam, to drive it through the scrub up in front of the motorcycle. (These men and women were all so competent.) There he tied on his yellow rope and towed the bike up and over that last hump. The trail seemed ridable from there, so I offered to take over from Tom. He snickered and said, "Sure - let me do all the riding, then take all the glory!"

The whole group of us, rescuers and rescuees, gathered where my bike had been delivered to the end of the gravel road. Earlier, after taking a few shots during a pause in pushing Michael's bike, I had passed my camera to John on his quad, asking him to take any photos he could. As we posed for a group shot at the end, with John's wife Pam holding my camera, someone pointed to it and said, "That is one dusty lens."

Sure enough, the photo was a bit blurry, but - historical.

It was at this point that I astonished Michael by introducing myself - by name and by profession - to our rescuers. I started by asking Tom, "Are you a fan of rock music?" He nodded tentatively, not knowing what I was getting at. Turning to face all of them, I said, "Well, I play for the band Rush. If any of you are going to be in Phoenix tomorrow night, I would like to invite you to our show."

Tom shook his head and said, "Whoa - I used to listen to Rush all the time." Then he made a wry face, "I just wasn't sure if you meant that modern kind of rock."

The rest of them seemed excited about the idea, so I brought out my little Montblanc notepad (always properly accessorized, even in the Outback), and they wrote down their names. Michael gave them his cell number in case they had any trouble picking up their tickets.

(Later he said to me, "Wow - after traveling with you all these years, I've never seen you ‘come out' before."

I fixed him with an ironic glare, "Someday you'll learn that there's always a proper time to come out.")

Our new friends looked at me with a little more "interest" now (I suppose to them, it was as if some kind of alien had dropped into their midst), but in a nice, easy, Western way. To me the important thing was that they had devoted all that time and effort to helping us - just because. I have learned from traveling in many inhospitable areas, from Africa to the Arctic to the American deserts, that people in such places band together. When you have a problem, if you are fortunate enough to find any people around, they are going to help.

(In this case, they even invited us back to their camp for steaks! We were certainly hungry - but we needed to move on.)

The sun was just setting as we fueled up at the Wayside - a funky desert oasis in the middle of the Outback, offering food, fuel, and RV spaces. With darkness coming on, we decided against the thirty miles of gravel that would bring us to the highway near Wickenburg - the nearest town where we might expect to find a motel and a meal. Instead we rode a few miles of gravel to a paved road, then down and around eighty miles. (Longer, but wiser.) The moon was nearly full, which cast a comforting light over the utter darkness of landscape and road, and the air was still warm. I rarely choose to ride at night, for reasons of safety and (lack of) scenery, but this was one enjoyable night ride, to a very welcome Best Western in Wickenburg, Arizona.

When Michael walked out of the lobby after checking us in, he was carrying two small lunch-size paper bags, and handed me one. "A present just for bikers," he said. The brown bag was decorated with the above artwork, by the owner's seven-year-old daughter - "because she likes motorcycles," the front desk clerk told us. (You have to love the "ya-hoo!" - and the "harley-davidson" on the tanks.)

When little Kenzie suggested to her parents that their motel should give motorcyclists a "special present," it was decided to offer these little bags - containing a couple of washcloths, for bike-cleaning (the darker reason for those being that too many riders use their room towels for that purpose), a Tootsie Roll, and a couple of hard candies. It was a sweet ending to a long journey.

As Michael remarked, "This has been the kind of day that raises your faith in humanity."

I agreed. The "better angels" had definitely been on our side, and it could have ended much worse.

But as I sat in the plastic chair outside the motel room with my Macallan, and tried to put down some notes about the day, different shades seemed to complicate the story. Not taking anything away from our rescuers (indeed, I will forever remember them with affection and gratitude), a reconstruction of events took me back to the hunter who told us, despite the "No Through Road" sign, that we could "make our way around." Maybe he was the kind of man who can never say "I don't know" (we've all met them), and felt compelled to offer that casual misinformation. Or maybe it was because he was sitting on a four-wheeler instead of a two-wheeler, and didn't know the difference in what we could "make our way around."

Either way, if that Thanksgiving Saturday had been nearly any other day of the year in that remote corner of the Arizona Outback, there would have been no one to ask. Our choice would have been between what the map and GPS said, and what the sign said. I am sure we would still have gone forward, but less confidently, and when the road petered out into nothing, we would have turned back - while we still could.

Then at that very juncture, that very point-of-no-return, we met Stephen and Karen, and they too had encouraged us, offering to lead us down a trail we would never have found, and which they couldn't know we wouldn't be able to ride.

So, I summed up the day with this little metaphor:

"People get you into trouble,

"People get you out."

Talking to the friendly front-desk guy, he told us the Rancho Grande Best Western in Wickenburg was one of the original five charter members of that association. That impressed me, because for many years that blue and yellow sign was my default choice in my random travels around North America. Up through the '90s, each property under the Best Western sign was independent and unique, and many of them were classics of the old-school motel - where you park in front of your room and walk to the attached restaurant. However, lately I had been disappointed to see the brand betray that heritage by devolving into an increasingly watered-down chain of corporate outlets. It seemed they were even buying up big-box joints from budget chains and calling them "Plus," when they were minus - the room-front parking, the restaurant, and the character.

Asking about restaurants for dinner, our front-desk friend highly recommended a nearby barbecue place, but they closed early. Michael and I were not ready to go anywhere - not even out of our riding clothes yet - so we opted for take-out. (Another key to a successful partnership: I think up good ideas - Michael executes them.) Still covered in the dust of the day's journey, we sat at the little table in Michael's room and tore into deliciously smoky racks and brisket and beans.

|

Desert Rat |

Back in January, when manager Ray first sent me the proposed itinerary for the tour, there were two features that immediately stood out to me. They were not the cities where I would be playing shows, because where I work doesn't matter much to me - not as much as how I get there. So my eyes tend to be drawn to the days off, and especially if I see two of them in a row. Those rarely come along (not "economically sound"), but can allow me to stretch my travel range between shows to some amazing journeys. One perfect example from a couple of tours ago: two days off between Phoenix and Albuquerque - the first day spent riding through Arizona to Monument Valley for the night, then through Colorado to Taos, New Mexico, for the second night. In this Bubba's touring life, it doesn't get much better than that.

This time, I was looking at two days off between Chicago and Detroit, which suggested interesting possibilities around the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. (That eventually became our sublime day off on Mackinac Island - see "The Better Angels.") The second pair of free days lay between Phoenix and Dallas, setting me up in the heart of the West. My first inclination was to aim for Southern Utah, with its unparalleled national parks - Bryce Canyon, Zion, Capitol Reef, Canyonlands, Arches - and one of my favorite destination towns, Moab. (Not least because it's in the middle of all that.)

But... it was November, and all of those places were cold, and potentially snowy. Another always-welcome candidate would be Grand Canyon National Park, but its low temperature at the time was 16 degrees. Oh, no. I would need to think "South."

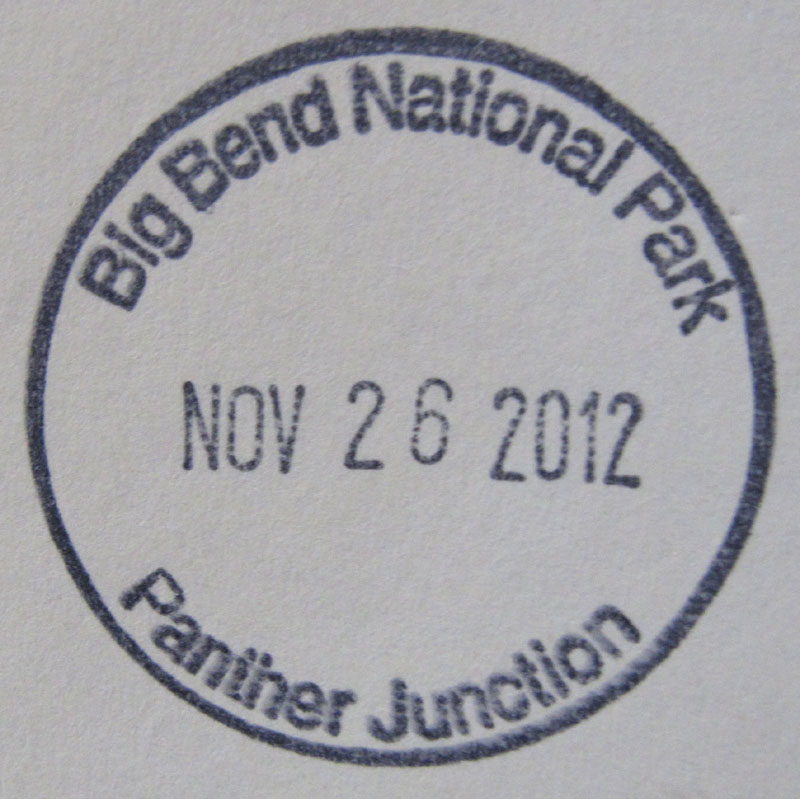

That spin of the compass needle directed me right to Big Bend National Park, way down deep in Texas.

For those two days we would be joined by a guest rider, Brian Catterson, longtime friend and veteran moto-journalist. (Like a number of my friends, we began as a "mutual appreciation society:" I liked his work; he liked mine.) As a traveler, Brian is a calm, competent companion (there goes that alliteration again), and had made an appearance on every tour since Vapor Trails, in 2002. Now just past fifty years of age, he had spent his professional life immersed in the sport and documentation of motorcycling. He was experienced in every kind of two-wheeled action, from extreme race machines to the light and agile motocross bikes of his youth. (We could have used bikes like that in the Arizona Outback!) Lately, after retiring as editor-in-chief at Motorcyclist magazine, he had returned to motocross bikes, as a hobby - or maybe a career. (My invented diner placemat of ads on Bubba's Bar 'n' Grill listed "Catterson's Small Engines," and we joked that it was coming true.)

|

Brian and Michael, Big Bend National Park |

I would find it impossible to name my favorite national park, among so many splendid places (truly America's crown jewels), like Death Valley, Yellowstone, or Bryce Canyon, but if I did try, Big Bend would be a contender. Other than Death Valley, it is also the national park I have most frequently visited.

Brutus and I first passed that way back on the Test for Echo tour, the first concert tour I did by motorcycle, in 1996-97. In March, 2003, it was the destination on the car trip that became the centerpiece of my "musical autobiography," Traveling Music. Since then I had led Michael there two or three times, often staying at the same fine resort in nearby Lajitas where Brutus and I had stopped for breakfast that first time.

It was Brian's first visit to Big Bend, and his first time seeing much of West Texas - our three-day journey would cover a thousand miles of Texas backroads between Van Horn and Dallas. Brian was usually content to ride behind Michael and me, and being on my spare bike (red, like every motorcycle I have owned), he called himself "the little red caboose."

When I led Michael and Brian up to the Chisos Basin area of the park, with its monumental rock formations and winding switchbacks, Brian said, "Mountains in Texas! Who knew?"

|

Chisos Basin, Big Bend |

I pointed over to Emory Peak, which I had hiked up during the Traveling Music journey in 2003, and told him it was almost 8,000 feet. Yet the Guadalupe Mountains to the north had a few peaks that rose even higher. Texas most assuredly has mountains. It's got pretty much everything.

Writing about Texas reminds me of trying to write about Africa - hard to describe to people who have never been there, or even to those who live there and haven't seen much of their homeland. The Big Bend area may be the most spectacular, but I also love the vast expanses of West Texas, the Gulf Coast around Corpus Christi and Padre Island, and east toward Louisiana, with bayous and cypress trees, the Piney Woods north of there, and the Hill Country west of Austin.

Texas truly is a country unto itself, beyond all the clichés, and its people are equally varied and unique. For example, it still remains true that rural Texans are the most courteous drivers in the country, perhaps in the world. Riding the two-lanes (which Brian was also delighted to see posted at 70 mph), cars, pickups, and larger trucks will pull right onto the shoulder as you overtake them. Sometimes you're not even thinking about passing them yet, but are willing to cruise behind them for a bit, but when they pull over like that, you feel you have to go by - always with a big wave.

|

Hill Country Byway |

Some readers might be surprised to learn that law enforcement is equally relaxed in Texas - especially compared to police states like, say, Ohio. In maybe 20,000 miles of riding in Texas over the years (over 2,000 just that week), I only remember being pulled over once - back in '97 with Brutus. Even then, the officer was friendly and let us go with a warning. Generally, if you respect the towns and villages, as we always do, you're not going to have a problem on the open roads. I have never encountered a speed trap in Texas, except on the interstate - and those speed limits are so high (80 on the long rural stretches), you've got to be pushing pretty hard to get into trouble even there.

Another part of Texas Brutus and I explored on that first tour was its most southerly region, south and west of Corpus Christi. That time we rode down from San Marcos, and stopped for breakfast at a tiny crossroads town called Tilden. I believe that was in November, too - sixteen years ago. I want to retell that story here, as recounted in Traveling Music, because now it has a different ending...

Somehow the open spaces on the map of South Texas had led us to expect a desolate land, but it was obviously fertile, and artfully cultivated. Plow and disk harrow had combed the brown soil into neat contours and swirls, like a Chinese garden, and the fields lay in elegant fallow. With my farming heritage and farm-equipment background, I had to admire this example of deft tractor-handling, and "excellence on earth."

The farms gave way to arid, rolling ranchland, and dark herds of cattle hunched under the dull sky. A pair of hawks flew between the few bare trees, their plumage dramatically patterned in dark and light, like magpies. The scrubby ground-cover was green with the recent rain, and occasionally dotted with small oil wells, a prehistoric-looking "dipper" rising and falling in slow-motion rhythm.

...

Thoughts of breakfast were beginning to gnaw, and I was tempted by signs pointing toward towns a few miles off our route, where we might find a diner. Many of the towns in that part of South Texas had names like Peggy, Nell, Rosita, Alice, Christine, Charlotte, Marion, Helena, and Bebe, and I imagined lonesome cowboys pinin' for the girls they left behind. (The female population of frontier Texas, like all the West, was probably half wives and daughters, and half prostitutes.)

Brutus and I rode on, pinin' for the diners we'd left behind. Finally we came to another little crossroads town, called Tilden, the seat of McMullen County. A new brick courthouse with a tiled roof stood on one side of the road, and opposite it, the Cowboy Cafe.

The walls inside were lined with rows of well-worn cowboy hats, each tagged with a name and year, and a poster for a '50s Western movie starring Rex Allen, the "Oklahoma Cowboy." A framed black-and-white glossy of Rex himself was autographed with folksy good humor, testifying that the Cowboy Cafe "filled us up real good."

Brutus and I peeled off a few more layers of clothing as Willie Nelson played on the radio, then sat down to the strains of "Don't Come Home A-Drinkin' With Lovin' On Your Mind." This late in the morning, the Cowboy Cafe had only one other customer, a silent man in a straw cowboy hat hunched over his plate. A tiny Mexican woman shuffled to our table, her crippled body barely as tall as we were - sitting down. She wore a large, shapeless T-shirt reading "Always A Lady," and her toothy smile and good-natured banter soon had us laughing with her. We looked at each other and smiled; this place was the real thing.

A tall, lean man came in, dressed in neat denim jeans and jacket, and a collared work shirt. He sat at the table beside us, saying "Morning, Gloria," and after a bit of banter with her, he leaned over to us. He looked to be in his fifties, his smooth-shaven face refined-looking, only mildly weathered by an outdoor life.

"I see by your licence plates that one of you fellows is from Ontario."

I raised a hand, "That's me."

He stood and introduced himself, shaking our hands. "I'm Johnny Nichols, and I run a ranch just down the road here. The man who first settled it was John Fitzpatrick, who come down from a place called St. Catharines. You know it?"

I laughed, "Sure do - I grew up there!"

"Right near Niagara Falls, right?"

I nodded, smiling.

"See, I've looked into it all."

Johnny Nichols sat down again as Gloria brought his coffee, then continued. "Uncle John, we called him, he come over to Canada from Ireland in the 1860s. He wanted to come down here then, but the Civil War was on, so he started farmin' up there. Then once the war was over, he worked his way down the Mississippi on the log booms, all the way to New Orleans, then made his way over here, and started runnin' sheep. A couple-a years later, his younger brother Jim followed him down, but one cold morning his horse was kinda skittish, and it reared up on him. Jim was tryin' to hold on, and his hand come down on the hammer of his gun and he shot himself in the leg. Died of blood poisoning."

We made the appropriate grimaces of sympathy and shook our heads.

"Then old Uncle John, he'd been battlin' with this neighbor of his for a long time over water rights, and things started gettin' bad. They all used to stay out on the range in tents, you know, and one day this neighbor come ridin' into Uncle John's camp, shootin' and hollerin', and Uncle John shot him out of the saddle, dead."

He paused for effect, then added, "But he got off for self-defence."

...

Then Gloria brought his breakfast, and a couple of other ranchers came in and joined Johnny Nichols at his table. All of them looked the part of ranchers and cowboys in their denim jeans and jackets, high-heeled boots, and hats.

...

Their conversation was sprinkled with the relative merits of petroleum, its color, pressure in pounds-per-square-inch, and the percentage of water they were pumping. Johnny Nichols shook our hands again as we left, and just south of Tilden we saw the sign arching above a sideroad, "Nichols Ranch, Est. 1879 by John and Maggie Fitzpatrick."

Their ranch had been established by "Uncle John" Fitzpatrick, who had made his way down to Texas from St. Catharines, Ontario, my hometown, way back in 1866. From then on that little crossroads town and county seat of Tilden, Texas, took its place on our "mental maps" for good, and we would never forget the Cowboy Cafe, or Johnny Nichols, or Gloria, or even Rex Allen, the "Oklahoma Cowboy."

The reason for that long digression (apart from correcting the spelling of "Nichols," and the wording on the sign), is because it describes a place and people that are now completely gone.

In the years since that first visit, I have often routed Michael and me through Tilden. It made part of a nice ride toward Padre Island, where I liked to stay between shows in East Texas. (Even just for the music of the surf through my open door all night.) On my second ride through Tilden, early in the 2000s, I was sad to see the Cowboy Cafe closed (replaced briefly by a barbecue place, which was also closed on my next visit a couple of years later). But the little town and the surrounding landscape of mesquite ranchland remained pleasant to travel through, on long straight two-lanes with little other traffic. As recently as June, 2010, I had passed through and found it unchanged.

This time, it was all different, and after what I had witnessed in Western North Dakota back in September (see "The Better Angels"), I knew immediately what was going on. It was those frackin' frackers. What Johnny and his fellow ranchers had been doing the old-fashioned way, pumping up a little oil more-or-less as a sideline, was now a vast industrial complex pumping chemicals two miles down to smash the oil out of the rock - "hydraulic fracturing," or fracking.

The West Dakota boom, on what was called geologically the Bakken formation, had been going for three years, while this South Texas operation, on what was called the Eagle Ford formation, had to be less than two. Doing some online research, the only date I found was 2011, so maybe only one. The machinery of modern fossil-fuel extraction moves swiftly, and massively. Hundreds of semis, crude-looking tankers and construction gondolas, crowded the little highways, warping the pavement into lumpy black dough that pounded us on the bikes. The mesquite scrub was lined with new fences of white steel pipe, pierced with dozens of gateways and raw gravel roads. Travel trailers stood at the gates with security guards in Hi-Viz vests, checking trucks in and out. Plumes of flame belched from high steel stacks, burning off natural gas, and vast construction sites for processing and storage works - enormous tanks, pumps, and pipes - were scraped out of acres and acres of mesquite. A huge truck stop was under construction near Tilden, and the ramshackle buildings that had housed the Cowboy Cafe were gone - completely obliterated.

The next town south, Freer, seemed to be the center of the boom, as it was of the region. Freer was surrounded by improvised RV parks spread out on acres of bare gravel, offering electricity, water, and - one hopes - septic tanks. Multiple signs advertised for truck drivers, and a brand-new Best Western glared with fresh paint in its unfinished gravel lot. Other construction sites rose up like broken teeth.

|

Calm and Timeless - Before the Approaching Storm... |

As I observed earlier about not taking pictures when things get too hairy, that is also true when things get too ugly. I hadn't taken any photographs of the devastation in West Dakota that time, and the only one I took around Tilden this time was the Nichols Ranch gate.

Comparing it with a similar photo I took in 2010, the fence of barbed wire and wooden posts had been replaced with the white steel pipes, but the most telling difference was the mailbox - gone now. Sad symbolism. No doubt before long the sign will be gone, too. Johnny and his family, like all the rest of the ranchers who once ran their cattle and pumped their watery oil above the Eagle Ford formation, don't live there anymore. (Echoes back to something I wrote in "The Better Angels," "The saddest roads in America are the ones where people used to live, but don't anymore.")

As I rode south from the old Nichols ranch on that pounded (and pounding) road, I felt sick to my stomach, and even a little prickly around the eyes. A place I loved like an old song, like an old friend, had been devastated. Nothing more than a sleepy little cowboy town, and some lonely two-lane roads between hardscrabble ranches in the mesquite scrub - but it had meant something to me. The mess in West Dakota had been shocking and appalling enough, but now it was personal.

Modulating to a more positive key, Michael and I ended the day with this view of the beach on Padre Island. (Yes, Texans drive trucks on their beaches - but I'm sure they still pull over to let you pass!) In late November, the beach chairs were piled by the concrete boardwalk and drifted around with sand. The offshore oil rigs were a further reminder of what I had seen that day, and the pipeline running across the beach seemed ominous - but apparently it only carried sand and water, to replenish the beaches after storms. And in the warm night, the waves murmured their steady, rhythmic music.

And getting back to music, as I would have to do the next day in San Antonio, the three shows in Texas marked the end of this year's part of the Clockwork Angels tour. For a few months we would be saying goodbye to our touring world - which, for me, centers on the bus, the Bubba-Gump room, the daily motorcycling, the backroads and motels, and, of course, the stage.

Before soundcheck at the final show, in Houston on December 2, the three of us gathered in front of the string players, which had become a daily custom. After they had tested their instruments and monitors, and before we all played together, I would sit cross-legged on the subwoofer behind my drums, while Alex and Geddy came in from their sides of the stage and we talked and joked for a few minutes with the "stringers."

By now the soundcheck routine was well established. Together we played the first half of "Clockwork Angels" and the first half of "Red Sector A," which checked out everybody's various "systems." Then the three of us gave sound engineer Brad the beginning of the opening song, "Subdivisions," so he was set for the start of the show. When Brad had heard enough, he would shoot up his hand for us to stop, and that became a game among us - watching for that upraised hand, and stopping immediately, laughing as we all froze on the same beat.

After soundcheck, dinner, and my warmup in the Bubba-Gump room, I changed into my "stage costume" and walked with Michael down the hallway to stage left. It was showtime - one more time.

One fun feature I have added to my performance this tour is the "T-shirt gun." For many years, at the beginning of our encore, Alex and Geddy have carried out baskets of bundled T-shirts and tossed them out to the crowd. That never appealed to me - not feeling comfortable in front of my drums - but somewhere I must have seen one of the air-powered guns that are used at sporting events to shoot souvenir T-shirts into stadium crowds. That, I thought, might be fun.

Michael soon took over as my weapons-handler, while John "Boom-Boom" Arrowsmith, our pyrotechnician and daily-events photographer, prepared the "ordnance" (T-shirts tightly bundled in fluorescent tape - so people can see them coming!). I run out for the encore, and Gump hands me the loaded gun. I climb up on the strings riser, and wait for the lights to come up on the audience (again, I want people to see the flying shirts - don't want anyone getting hurt). I fire the first two rounds, then bend down to let Michael reload while I turn the dial to prime the pressure. Soon we had it down to a tight routine, and were getting off four separate shots. Then I would lay down the gun and scramble across the subwoofer to the drums, ready to start "Tom Sawyer."

At first I was shooting T-shirts with my "yearbook" photo from the tourbook - created by Geddy for all three of us on an app called Oldbooth - then one with my "g'nome" character on the front, and finally a West Side Beemer Boyz version, with a riding shot on the front, and one of my favorite maxims on the back, "The Best Roads are the Ones No One Travels Unless They Live on Them."

Here is a great shot by Boom-Boom, showing the first shirt in flight, and the second just leaving the muzzle. Michael waits to load the last two shirts.

One aspect of my "distribution system" that particularly pleases me is that my T-shirts go high into the crowd - "far and away" - into the less-expensive seats. Consequently, I have never seen anyone down front wearing one of them at another show, as I regularly see the ones Alex and Geddy toss into the front rows.

After thirty-five shows, and 13,632 motorcycle miles, we finished the Houston show on a very high note, so to speak. The performance itself felt triumphant, and after, we gathered with the stringers for a champagne celebration. It was the first time I stayed after a show on the whole tour, and a couple of the stringers joked that they were used to seeing me as a blur on my sprint to the bus.

A few nights earlier, when we were filming some shows for an eventual concert DVD, director Dale had a cameraman trying to capture my flight. He caught a comment from a female security guard, an older lady with a broad New York City accent. She turned in amazement as I ran past, and gasped,

"Oh my god! He runs faster than Britney Spears! And she was running full out!"

But on this night I stayed behind, and raised a glass to my bandmates - all ten of them! Geddy proposed a toast to the stringers, and said that not only did we love their contributions musically, and the energy they brought to their performance, but they were fun to hang out with, too.

He nodded toward me, and said, "I've never seen him so happy on a tour! He's been...Mr. Goodvibe!"

|

Love Notes |

Nothing wrong with that, obviously, but I was a little mystified. I hadn't actually felt any different. Maybe the "deeper currents" of my being were calmer; my inner compass steadier - I don't know. Fundamentally, I liked the way I was playing, and felt strong and consistent from night to night. I was beginning to master the improvisational mode I had been pursuing for several years - and in three different solo contexts throughout this show. (Michael calls the third one, on the electronic drums, the "Binary Love Theme." He says that's where I play the "love notes," as opposed to the "hate notes" on the acoustic drums. Or the "gay notes" on the piccolo snare. He is a very disturbed man.)

Just before soundcheck at the Seattle show, I recorded a radio interview with Michael Shrieve (veteran drummer with Santana, Go, Automatic Man, and more). In my early drumming years, Michael was a strong influence on me - his legendary solo with Santana in the Woodstock movie a formative paradigm. All these years later, drums were a kind of religion that the two of us shared - we could easily have talked for hours. During our conversation, Michael mentioned the resonance for him of a quote I had used in Bubba's Book Club.

|

Classic Arena Backstage Scene - Bus, Trailer, Bikes, Dumpster |

"The most valuable of all education is the ability to make yourself do the thing you have to do, when it has to be done, whether you like it or not."

(I didn't remember the source, until Michael told me it was Aldous Huxley, from my review of his novel, After Many a Summer Dies the Swan.)

So, considering my recent life in those terms, for all those months I had been doing what I had to do - my job. But I had also been doing what I wanted to do: making that job as interesting, challenging, and rewarding as I possibly could. (Everyone knows it doesn't always go that way.)

Musically and visually, I was proud of the show we were presenting - the overall production, and aspects like the alternating sets, with a few different songs from night to night. After thirty-eight years together, I was confident that Clockwork Angels was our masterpiece, and I felt that the string section during those songs elevated our whole "presence." Drum tech Gump had been keeping our elaborate setup perfect, and any glitches had been few and minor. With regular treatment and a brace when I played, my aching elbow ("lateral epicondylitis") had held out for the duration, without inhibiting my playing. (I think I wrote once before, "If I'm not happy on the drums, I'm not happy anywhere.") On my bus, Dave and Michael and I had a comfortable routine, and my motorcycle explorations had been entertaining and rewarding.

And now I was going home to my family for a nice long rest, before starting up again next spring and summer. Soon three-year-old Olivia and I would be walking down the streets of our neighborhood, singing a new song we made up together:

"I'm so happy ?

I'm so happy ?

I'm so happy - to be with you!"

Somehow I know that when Michael rides behind me again, in a Midwest monsoon, a snowy Oregon road, or a cloud of Wild West dust, he will sing that same song. But with some bad words added...