The Story Of The Drum Solo

The History Of The Solo And Its Place In Modern Drumming

By Geoff Nicholls, Rhythm, December 2013, transcribed by John Patuto

Like a good tune and a sweet vocalist, a drum solo must captivate and entertain its audience. Today's modern drum kit was settled by the 1930s when Gene Krupa became the biggest star of the big band era. Somehow we have to imagine how the drum kit was seen back then - still a thrilling novelty, enough to make Krupa's wild tom tom barrages and snare rim-shots the focus of major Hollywood Movies. Just imagine that today...

Through the 1940s Buddy Rich's virtuosity blew minds, stealing the show on stage and screen. Then during the 1950s another shock came with the emergence of teenage rock'n'roll and the 'deafening' electric guitar. In those naïve days, Sandy Nelson's drumming instrumentals topped the singles charts. And as jazz lost its commercial appeal, grown-up rock drum solos arrived big-time with Ginger Baker's ground-shaking 'Toad'. Rock, prog, heavy metal, jazz and fusion drummers vied to create the most brilliant solos.

Then it all went underground. In the UK, punk halted any display of instrumental virtuosity and the rock drum solo was despised. It was still a vital part of jazz, but in commercial genres survived only in heavy metal and prog. Phil Collins' drumming duets lit up Genesis shows, Neil Peart emerged as one of the most hero-worshipped drummers ever and Tommy Lee took the show to the circus. Drumming skills have since climbed unbelievable heights, but the public is largely unaware of this. The time for the next drum soloing star to emerge, a successor to Gene and Buddy who thrills public and critics alike, still seems a way off. But in the meantime Rhythm salutes the long and brilliant history of the drum solo, and asks some top players what soloing means to them.

The drum solo is as old as the drumset itself. The kit began taking shape in the 1920s in New Orleans, where Warren 'Baby' Dodds became the pre-eminent stylist with King Oliver and Louis Armstrong. He was more of an accompanist than a soloist with his 'shimmy' beat, and recording techniques were too primitive back then to capture the kit properly. But he can be heard and seen on later, insightful solo demonstrations like 'Spooky Drums' (1946).

THE BIG BAND ERA

History has recognised the first great drum soloist in William Henry 'Chick' Webb, 'The Savoy King', who led his own orchestra at the Savoy Ballroom in Harlem from 1931 to 1939. His machine gun snare rolls and ability to set up dynamic big band figures set the mould for the whole big band era. Check out 'Liza' (1938) and you'll hear why Gene Krupa admitted that "Chick Webb cut me to ribbons". It was Krupa who became the most famous drummer ever and inspired virtually every other drummer, through to the rock stars of the 1960s. He assembled the first truly modern kit with tuneable double-headed toms, and played solos with a wide-eyed exaggerated style, faithfully copied by Keith Moon three decades later. You still regularly hear 'Sing, Sing, Sing' (Benny Goodman, 1937) with its infectious floor toms today.

Big band swing was the popular dance music through the 1940s and 1950s, and the showman drum solo was a highlight of the evening. Every top band had its own drum star, like Buddy Rich, 'Papa' Jo Jones, Ray McKinley, Dave Tough and Ray Bauduc.

JAZZ GROWS UP

Emerging later in the 1940s, bebop was small group music with a modern, fast and angular approach. Gretsch introduced diminutive 20"x14" bass drums and small kits that accommodated the breakneck tempos. Kenny Clarke, Art Blakey and Max Roach pioneered the new style. This was music to hear in small clubs, not to dance to in large ballrooms. Roach and Blakey played solos at lightning tempos, keeping pace with the improvisatory brilliance of Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie.

Listen to Max Roach on 'Cherokee' (1955) and Art Blakey on 'Mosaic' (1961) and 'Caravan' (1962), mixing insane ride cymbal-driven tempos with Latin-derived bell work and Afro-Cuban 6/4 grooves. Both drummers composed melodic solos following song form, Roach famously on tracks like 'The Drum Also Waltzes' from Drums Unlimited (1966) - a piece much copied by Bonham, Bruford, Peart and others. Max even took on Buddy Rich in a 1959 drumming album Rich Vs. Roach - a full-on meeting of two great stylists and pioneers. Post-bop, hard bop, modal and free jazz drummers like 'Philly' Joe Jones, Roy Haynes, Shelly Manne, Elvin Jones, Don Moye, Rashied Ali and Tony Williams and Jack DeJohnette in the 1960s extended the small group vocabulary.

By the 19505 the big swing bands were feeling the pinch, but continued side-by-side with the small post-bop, modern and cool outfits, and eventually the first rock'n'roll bands. Each genre had its drum heroes. Louie Bellson's 'Skin Deep' (Duke Ellington Orchestra, 1951) ushered in the era of double bass drums, continued by Louie's successor Sam Woodyard. Count Basie's drummers, Sonny Payne (one of the all-time great stick jugglers) and Rufus 'Speedy' Jones, were spectacular players with their own brands of soloing and showmanship.

ROCK'N'ROLL JOINS THE PARTY

The novelty of early rock'n'roll and the newly liberated electric guitar meant that, for a while, instrumental groups were chart toppers. And a handful of instrumentals were drum features. Veteran jazz drummer Cozy Cole had a surprise hit with the million-selling 'Topsy, Part II' (1958), which impressed a young Ringo Starr. Cole had been one of the first ever to record a drum solo, 'Load Of Cole' in 1930 with Jelly Roll Morton.

Even more prominent, the American Sandy Nelson scored international hits with 'Teen Beat' (1959) and 'Let There Be Drums' (1961). But perhaps the biggest of this first crop was 'Wipeout' (1962), a surf beat sixteenth-note tattoo, thrashed out enthusiastically by the 17-year-old Ron Wilson with The Surfaris. In the UK the two Shadows drummers Tony Meehan ('See You In My Drums', 1959) and Brian Bennett ('Little B', 1962) were exceptionally skilled by early DIY rock-pop standards, setting a high benchmark for the British drummers to come.

All these pop solos were still heavily influenced by the jungle toms of Gene Krupa. But another, more subtle influence was that of Joe Morello. Dave Brubeck's 1959 'Take Five' (With its drum solo in 5/4 time!) is the best-selling jazz single ever. Morello's silver Ludwigs also presaged the rock invasion with their deep bass drum and fat toms, unlike the hard and tight sounds of bebop. Morello thus became as big an influence on rock drummers as Buddy Rich.

Yet the first drummer to really lift rock into the grown-up sphere derived his inspiration from elsewhere. In his solo 'Toad' (Cream, 1966) Ginger Baker employed double bass drums and RLFF-type patterns (inspired by Sam Woodyard) that have been an absolute staple of rock solos ever since. Meanwhile Buddy Rich, already a legend, achieved perhaps his greatest moments when he reformed his big band (against all music industry trends) and finally arrived in the UK. Showcasing his new signature 'West Side Story Medley' (1966) with devastating fills and climactic solo, Buddy would be a UK hero from then on. Buddy's all-round paying and solos, including the follow-up 'Channel One Suite' (1968), are widely considered the greatest displays of drumset mastery ever seen.

The decade closed with Led Zeppelin and John Bonham. Bonham's reputation has expanded with the passing decades. His mammoth solos on 'Moby Dick' referenced not only Ginger and Buddy, but Joe Morello's bare hands soloing on 'Castilian Drums' (1963). A golden generation of British drummers - Mitch Mitchell, Ian Paice, Bill Ward, Carl Palmer, Jon Hiseman, Clive Bunker, Barriemore Barlow and others - all offered up marathon solos nightly.

PROG, METAL AND JAZZ-ROCK

Into the 1970s the drum kit expanded exponentially. A new breed of heavyweight jazz players, led by Tony Williams, Billy Cobham and Lenny White, allied stupendous jazz chops with rock power and gave us jazz-rock fusion.

Cobham left jaws on the floor with the Mahavishnu Orchestra and his 1973 masterpiece, Spectrum, the ultimate drum-led album mixing funky tunes and grooves with incredible soloing. Billy's double bass drum boogie 'Quadrant 4' led directly to Simon Phillips' Space Boogie' (Jeff Beck, 1980) and Alex Van Halen's 'Hot For Teacher' (Van Halen, 1984).

The 1970s was also when hitherto unheralded session drummers came to be very cool indeed. Steeped in jazz and r'n'b, Steve Gadd allied passion with a super-clinical accuracy. In 1977 he recorded Steely Dan's 'Aja', nailing the complex eight-minute track in a single take, reading the part cold and culminating with the most hip drum solo imaginable. Back in the UK, prog gave us Carl Palmer who combined classical percussion with rock, while in Genesis Phil Collins and Chester Thompson delighted with their dual-kit solos. Thus inspired, Rush's Neil Peart, bucking the growing anti-muso trend, staged multimedia solos on fabulous drumsets, eventually combining kit with percussion and electronica. Neil caught the imagination of fans worldwide who to this day worship him as a drumming deity. Terry Bozzio went even further with his unique solo composition concerts for a monumentally expanded drumset.

THE MODERN ERA

Post-punk, metal and prog continued to throw up great players and move the art of drumming in new directions, particularly in the furtherance of four-limb coordination and double-bass drumming. Eyes were opened by the Cuban Horacio Hernandez playing cave with his left foot while soloing with the other three limbs.

The possibility of such seeming independence would have been deemed impossible a generation before, but now led to a new breed of super talents like Thomas Lang, Marco Minnemann, Mike Mangini and Pete Zeldman who befuddled the average -- drummer with their fantastic multi-pedal orchestrations. And over in the metal blastbeat corner the double bass drum speed and dexterity of Derek Roddy, George Kollias, Gene Hoglan, Pete Sandoval and the rest was frankly incredible.

But let's not forget, the drum solo has all the while continued to evolve in its natural home of improvised jazz. Brian Blade, Bill Stewart, Peter Erskine, Martin France, Jeff Hamilton, Jeff 'Tam' Watts, An Hoenig, Lewis Nash, Dave Weckl, Vinnie Colaiuta and many more continue to beguile us with their lifelong pursuit of the ultimate musical solo.

THE MODERN DRUM SOLO

Nothing divides people like a drum solo. Lacking melody and harmony, many believe the drumset is best kept to its primary accompanying role. But there are many different forms a solo can take. Drum soloists are expected to excite, but solos can also be tasteful, thoughtful and even melodic. In both jazz and rock a drummer might 'trade' two, four or eight-bar phrases or fills. A solo might follow the song form in eight, 32 or 12-bar sections. Some compositions are specially written to feature the drums, while some of the tastiest soloing occurs when the drummer stretches out over an ostinato phrase or vamp. Then there is the major drum feature, where the drummer is given complete freedom.

One of the world's most accomplished all-round drummers, Steve Smith, says: "I have no preference, I like all forms of soloing and have worked on everything [Vital Information, Hiromi Trio, Zakir Hussain, Journey]. I've always taken soloing seriously and have been called upon to solo in almost every musical situation I've been in. Most jazz gigs require the drummer to provide a solo voice equal to that of the other musicians. With [pianist] Hiromi, [guitarist] Mike Stern and Vital Information, I solo in at least half of the songs we play. That is exceptionally demanding and requires a large vocabulary so that I don't repeat myself solo to solo, or night after night."

Another drummer equally adept at jazz or rock is the UK's Ian Thomas [Eric Clapton, Mark Knopfler, Tom Jones, TV/movies, Laurence Cottle, David Sanboum]. He says, "I much prefer to play it over a sequence, over a tune you can quote or can be singing in your head. You can play musically rather than in a drumming-gymnastic way. I soloed in [Hamish Stuart's] 'Queen Of My Soul' and sometimes everybody stops and for me, that's the worst thing - I want something to play off. So I asked Will [Lee, bass] if he'd keep some ostinato under me, holding it down. It makes sense to the audience, rather than [being] something that has no reference point."

Although professing to not enjoy soloing, Gavin Harrison says, "There is a song we [Porcupine Tree] play called 'Hatesong' and we improvise over the ending, and it sort of turns into a drum solo and guitar solo together, and that is interesting in much the same way as in jazz where the band plays a vamp and you solo over it. And I do a couple of small solos in 05ric, always over a vamp. I never liked those solos that went on for so long no one knows where the beat was, including the drummer, and the tempo has gone out the window and in the end he or she has to turn round and shout, 'One, two, 1-2-3-4...' That always seemed a dreadful failure to me!"

TELL A STORY

Cut loose and free to solo at length, there is even more need for structure. Funk giant John Blackwell Jr [Prince, John Blackwell Project, Justin Timberlake, Cameo, Maze] explains, "My approach to a solo depends on the moment and the type of music that I'm doing, but no matter what, I always want to tell a story. A story has a beginning, middle and end. I feel if I don't approach it that way, then it doesn't make sense to the audience or to myself. To me you're just talking and saying nothing."

Dream Theater's new super-technician Mike Mangini also aims to tell a story. He says, "I construct a solo based on the same rules that would make a written essay, meaning ideas that transition in some way and have a mechanical connection from statement to statement to the end. The ideas, or sentences, are a combination of the best technical things I can play given the parameters of musicality. I can't just throw ideas in, I have to use the ones that are most fun to play but that work together in a way that comes across as palatably as I can, based on the rules of good storytelling."

Steve Smith elaborates: "When it comes to playing unaccompanied drum solo pieces I have a variety of approaches. Establishing melodic themes, playing over a foot ostinato or a left hand ostinato or a combination of foot and hand ostinatos. Over that, I develop themes and melodic rhythms. As for form, that's wide open. The solo can use a simple A section, B section concept, or more extended versions where there may be three to four different parts. My solo pieces tend to have sections that are composed and then improvised, much like playing a song."

ROLL OUT THE SHOWMAN

Whatever the structure, drummers regularly have to contend with the public's perception that drum solos should be visceral, visual and entertaining. John Blackwell is cool with this: "I think that showmanship is very important, especially in shows with artists like Prince and a few others I play with, because you want to entertain the people that came out to see you. It makes you creative. For example, I spray my sticks with fluorescent paint and use them only in a certain part of my solo if I'm playing for a pop or funk group, and that always wows the crowd."

Arejay Hale [Halestorm] agrees. "I always found solos somewhat unexciting when the player didn't interact with the crowd. It always seemed like the drummer was just playing for himself. My approach is to make it feel like the whole crowd is a part of it. It's more fun for me and for them, to interact and get them involved. It's my duty to take over the show like a 'frontman behind the kit' for the solo and really have fun with the audience. I like using electronic pads to make weird space sounds, I've even used dubstep samples. Sometimes I'll do a call-and-response with the crowd, smash my gear, jump up and down, kick my cymbals. I'll solo with just my hands or giant sticks. I want people to leave with something unique and fun to take home."

Mike Portnoy remembers his Dream Theater solos. "In the 1980s/'90s I was more of the Neil Peart type of soloist, into the chops and the spectacle with the huge drumset. I stopped doing solos because I felt it was redundant, but my last couple of years I was going more for the Tommy Lee, entertaining approach. I'd take a tom and walk out to the stage front playing on the tom, on the floor, the mic stands and then [getting] drummers in the front row that I saw playing air drums and I would have them play on the torn with me. Whoever was the best I would bring up to my kit and let them solo with me on stage."

GIVE US A TWIRL

For John Blackwell, a keen student of drumming history, showmanship started early. "I learned how to twirl sticks when I was 14 at Keenan High School in South Carolina. To this day, you can go there and see kids of 10 doing things with sticks that I probably did not learn or could not do. Keenan's marching drum section was always being challenged by other schools to see who had the best dance moves, the combination of rudiments and choreography with stick twirls. It was a really serious situation, to the point where if you could outdo the other drum section they would resort to fighting to see if you could outdo them that way. That's when I ran!

"After Keenan I went to Berklee College of Music. I practised for hours trying to figure out how to use the stick twirls I learned at Keenan around the entire drumset. I would go to the video library and watch drummers like Gerry Brown, Lionel Hampton, Sonny Greer, Sonny Payne, Carmine Appice, Dino Danelli, Jonathan Moffett and Sonny Emory. These drummers became a big influence, but I wanted to do it my way, so more hours were spent coming up with my own way of doing things."

Slipknot's Joey Jordison, following in the Tommy Lee tradition, has gone to extremes to make his audience gasp. Even while coping with sophisticated props, Joey finds room for variation: "I have never constructed a solo, ever. That is kind of weird because all of my drum solos with Slipknot have been half-drum solo, half-theatrics, with me being flipped-upside-down and all that. My solo is limited because I'm in a five-point harness and the chair is back from my drums a little so they're harder to play. I adapted to be able to play like that and still play a solo. One day I'd like to play a solo without worrying if I'm bolted in right, but it's all for the show and you can still see all my characteristics in my solo. I have to think about my balance too when I start tipping forward - it's like a rollercoaster and your whole body wants to fall and your arms want to hang. I've got to pull myself all the way back, and that is extremely hard to do while I'm playing all of these crazy 32nd notes and hitting cymbals."

With his advanced concepts, Mike Mangini is conscious of not losing the audience. "I have to make it for everybody," he says. "There are so few of us that have wired our brains to even begin to comprehend and recognise so many patterns that are so easy to do once you put in the work. Most people don't recognise a base time, a feeling of 11 while a pattern of maybe five of those 11 notes is occurring at the same time. I have to tailor my solos to people who are not musicians, I can't expect them to do the studying. They want to see sticks being spun and the guy that flips upside down. That drummer might be more entertaining. You need to please those people. I don't judge that, I think all of that is tremendous and needs to be valued."

COMPOSED OR IMPROVISED?

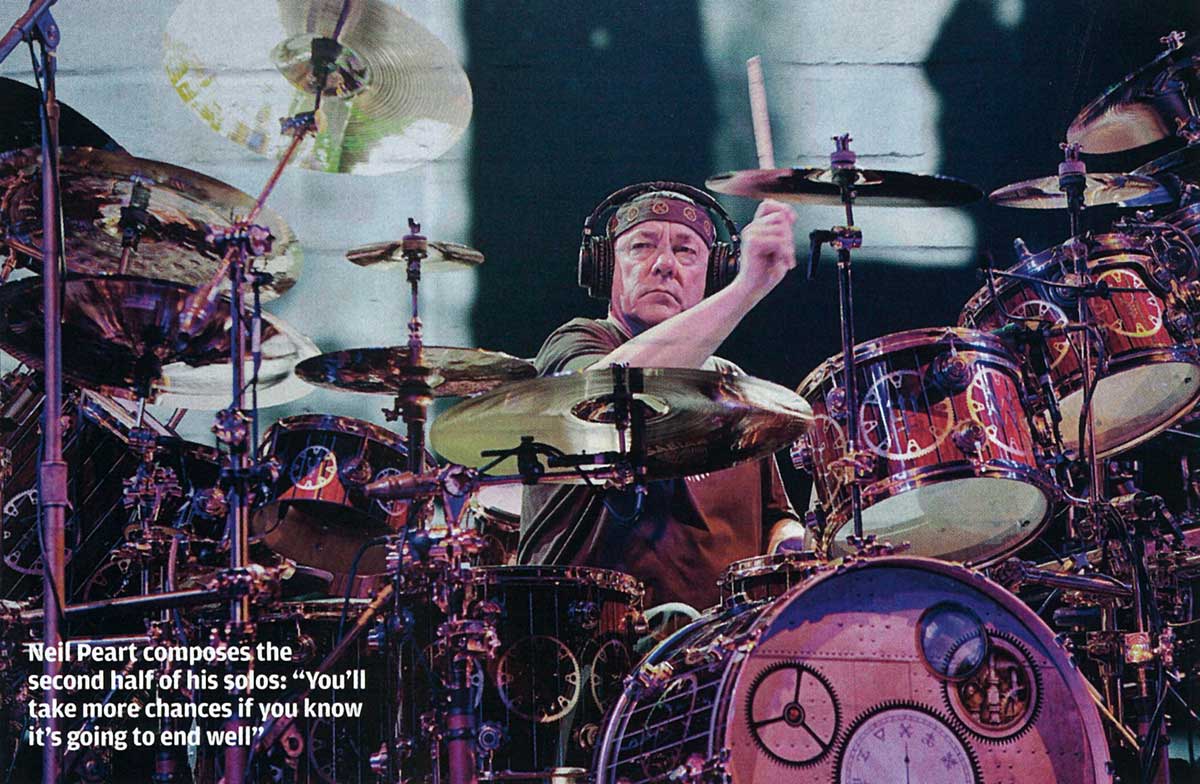

Improvisation is the soul of jazz but, in a more commercial show, how prearranged does a solo need to be? John Blackwell warns, "A solo should not ever be practised, because it will never come out the way that you practised or wanted it to be." And even Neil Peart, known for his meticulous approach to his drum parts, told Rhythm, "I might work on something in my warm-up routine, and it's in my solo that night. I cover myself in that the second half of the solo is well organised, and presented for the audience as a performance piece. You'll take more chances if you know that it's going to end well. I actually found it daunting in one way but exciting in another. Before that show, that's one thing I know that I don't know - the songs are laid out and most of our-arrangements are pretty tight, but there's that edge of, 'What'll I do tonight? Where will it go, where will it take me?"

Elaborating on the way he balances compositional and improvisational elements, Neil added, "Freddie [Gruber, renowned drum teacher] had defined me as a composer. He said, 'Look, when you play, you're composing.' And I accepted, yes, I'm a compositional drummer and when I did the Anatomy Of A Drum Solo video I defined myself that way - 'I composed this solo and I play variations within the movements but it is a composed piece.' Then right after that I went, 'Well, I want to improvise. I don't want to be just a compositional drummer.' So I deliberately set out to learn that, within the context of my solo, making the first half of it improvisational over three different ostinatos, and then the second half was composed so I know it is always going to resolve into something from the audience's point of view."

Neil largely paved the way for Mike Portnoy, who reveals, "When I did the big solos [in Dream Theater] I was completely flying by the seat of my pants. I would have no idea how it was going to start, finish, and what was going in the middle: It was always, from night to night, a spontaneous reaction to the moment. Usually I would know the ending, a way to get out, and that would serve as the cue to the band members to get back on stage. To this day, every fill I play in every band is in the moment and different from show to show."

To have this amount of freedom though, you need a wide vocabulary and the confidence to go for it. Ian Thomas says, "I obviously have muscle memory and little licks that I will play more often than not, but there is no predetermined order. I think about the tune first and let my hands roam about and see what they come up with, and that way I think you are properly improvising, rather than, 'I'm going to do this lick followed by that lick.' And yes, there might be a bag of things I play regularly, but they can be joined up in completely different ways that are relevant to the tune. It doesn't always work of course, sometimes it's better than others. And some of the best things happen when you screw up.

"Say you are playing over a sequence, you can play over bar lines and get yourself into a mess, and you have got to get yourself out of it. Saxophonist friends say the good stuff happens when you are trying to get out of a mistake. And if you are not brave enough to make a mistake, you are never going to know. You have got to be brave enough to mess up."

DRUM CLINICS

In-the-moment improvisation differs significantly from carefully prepared clinic performances. Gavin Harrison advises caution. "When you are young or an amateur the thing that stifles you the most is lack of technique, so when you see a drummer playing with a lot of technique it impresses the hell out of you, just on a physical-mechanical level. You are so impressed that this guy can go so fast you are not listening to whether it is musical. But don't get confused between technique and music. Nine times out of 10 it is not music. I would be just as impressed watching a gymnast do incredible things on the bar. Is it art? A contemporary dancer would say that is not art, it is gymnastics."

Steve Smith makes a similar distinction. "Becoming famous in the drum world for being a good clinic soloist, and being a successful drummer in the music world, are two different things. The common ground is musicianship. If you have developed your musicianship then you can be both successful as a clinician and be a successful, employable player. Some drummers who are successful in both worlds are Steve Gadd, Dave Weckl, Russ Miller, Keith Carlock, Jojo Mayer, Aaron Spears, Gregg Bissonette, Simon Phillips, Daniel Glass and Gavin Harrison."

But clinics can have other benefits, as Steve reveals. "I've been able to develop my solo playing by doing clinics. And drum festivals are the last place that players of every musical genre can all play on the same bill and find an open-minded audience. That was the beauty of [innovative concert promoter] Bill Graham's concerts in the 1960s. He would have the Grateful Dead share the bill with Charles Lloyd with Jack DeJohnette on drums. Or book the Miles Davis Quintet with The Steve Miller Band. The only place you can find that kind of openness today is at drum festivals. And it works! You'll find Jeff 'Tain' Watts on the same bill as Jason Bittner, and the audience respect both players."

SO IS THE SOLO ALIVE AND WELL?

Most drummers love to witness great soloists and today drum clinics/fests are where you can see them up close. But is there a move back towards accepting solos and drum musicianship in the more mainstream music scene?

Mike Portnoy thinks so: "[Over] the last decade it's become cool again to play an instrument. Games like Rock Band and Guitar Hero helped make it acceptable again for people to try to be good musicians. All the years I was in Dream Theater that was the biggest struggle - for us to gain recognition and acceptance, and I think we finally did. Now the bar is through the roof. You look at YouTube and there are 10-year-old drummers that are doing s**t that I can't do, no way. There are kids out there raising the bar daily. It's amazing."

"My feeling is that the drum solo is alive and well in the idiom that it really suits, which is jazz," concludes Ian Thomas. But what about outside of jazz? It's drummers like Portnoy, mostly in prog-and metal, who have kept the solo alive in rock. Steve Smith suggests that "musicianship and virtuosity are held in high esteem in these genres and most virtuosic players like to play solos! From my perspective, being a strong player is to be equally proficient as an accompanist and a soloist. In the pop world, songwriting and singing reign supreme and musicianship is valued to the degree that it serves the writer's or singer's vision. If a band or singer has a drummer that can really play, then hopefully they have a solo in the show. Then it's my hope they create a solo that succeeds on levels of musicality and general audience entertainment. I've recently seen two very good drum solos at rock shows: Marco Minnemann with Joe Satriani and Mike Mangini, playing one of the most amazing drum solos that I've ever seen, with Dream Theater. Vinnie Colaiuta stretches with Sting and Keith Carlock gets to blow over 'Aja' with Steely Dan. And I hear that Tony Royster Jr gets to solo with Jay-Z and Aaron Spears with Usher, which is cool... those cats can play!"