Neil Peart On Drum Solos

By Neil Peart

Rhythm, Part 1 - March, Part 2 - April, 2014, transcribed by John Patuto

Part 1

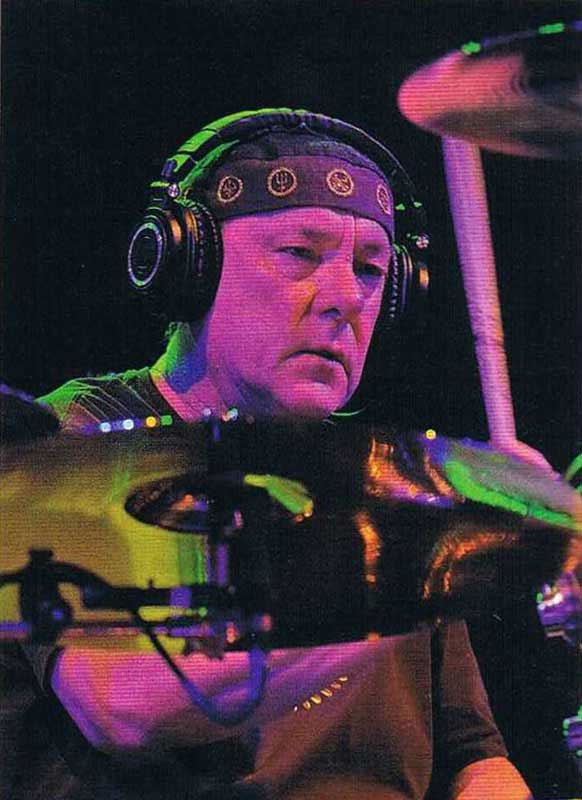

In the first of a two part feature on his approach to soloing, Rush's Neil Peart breaks down one of his Clockwork Angels solos and explains why it's 'all about the drumset'

When I wrote to a friend that I was working on a story about my drum solos on the Clockwork Angels Tour DVD, and about drum solos in general, his comment was to send me an Alice Through The Looking Glass illustration (pictured to the right). Too perfect!

I fear that is how all drum solos sound to many people, and that's too bad. However, I believe most humans can be stirred to their cores by rhythmic drum patterns - it is surely the oldest music. If a drummer can combine that primal instinct with structure, conversation, invention, and a touch of theatre, the audience will be reached, even moved.

Since my first-ever performance on the drums at a high school variety show in 1967, I have played drum solos in every band I was part of. My solos have evolved as I have - even fed that evolution, as the experiments and technical exercises of soloing increased my drumming ability in every application.

So... I hope we can agree that drum solos can be good for the drummer, good for the audience, and good for other musicians. (Break time!)

Right from the rehearsals for the Clockwork Angels tour, in the summer of 2011, I was excited to find myself with three completely different 'frames' in which to solo - opportunities to explore separate interpretations of what drum solos can be. It was also a healthy change from previous tours, in which I always performed one 'extravaganza'. For the past 17 years the band played two long sets with an intermission, and my solo was always in the middle of the second set. This would shake up that habit as well.

The first 'seed' of these changes came about when we were mixing the Clockwork Angels album. Here's how I described it for DW's Edge magazine:

In the recent past I had always performed a long solo, around nine minutes, somewhere in the middle of the second set. But... during the mixing of Clockwork Angels, our co-producer, Nick Raskulinecz, an irrepressible 'enabler,' insisted that I had to do my solo out of the drum break in 'Headlong Flight'. It happened that that song would appear around the middle of the second set, but - íJesu Christo! -'Headlong Flight' is a fast-paced seven-minute song, in the middle of a fast-paced hour-long performance of the Clockwork Angels songs, with another 30 or 40 minutes still to go. Plus coming out of that drum break I will still need to drive through a long guitar solo, another verse, bridge, and a double chorus, all at a fast tempo.

To say the least, it was daunting. But... once again I applied some 'polyrhythmic thinking'.

What if I did two shorter solos, one in each set? Ooh, yes - that had possibilities. Eventually that notion evolved into three 'excursions'. The first was a more traditional solo in the first set, in the middle of an instrumental called, 'Where's My Thing?' (Thus the solo is smilingly titled, 'Here It Is!')

In the middle of the second set, I would take an extended drum break in 'Headlong Flight', for which I incorporated samples of the bass and guitar parts - wanting to create a version of one of my most admired soloing approaches, as exemplified by Steve Smith or Dave Weckl, for example. I speak of 'soloing over the changes', where the solo holds the tempo and structure, while the band joins in on specific hits or phrases. I have not yet convinced my bandmates to help me create that exact 'set-up', but this is a fun approximation. One superior element is that because I trigger the 'accompaniment', I can improvise freely against a set of changes that is random, rather than arranged.

Finally, late in the second set I would perform a stand-alone piece on the electronic drums, combining more melodic synthesized sounds from a Roland V-Drum patch called 'Melodious', and another array of sampled sounds selected by me and the band's longtime programmer, Jim Burgess, which was more 'cinematic' in concept. (We called that set-up 'Steambanger'.) Here is a more detailed look at each of those solos, beginning with comments by Rhythm's Geoff Nicholls.

'Where's My Thing?'

'Here It Is!'

Very much a powerhouse drumset solo in the more traditional sense (band leaves the stage in 1960s/'70s style - and need a strong cue to come back in), but with the electronics, effects, and triggering adding a sonic and dramatic boost, perfect for stadium-sized shows. So this is the drum solo expanded by electronics, while never losing sight of the fact you obviously love playing the acoustic drumset (perhaps still first and foremost?).

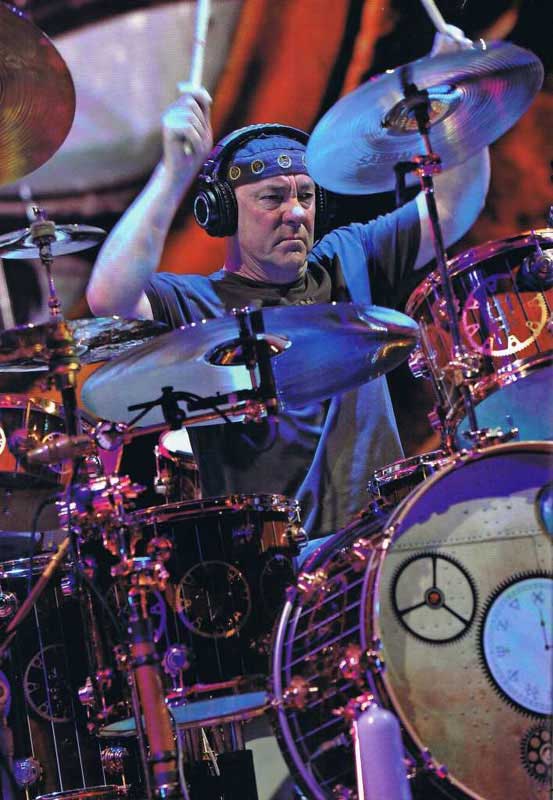

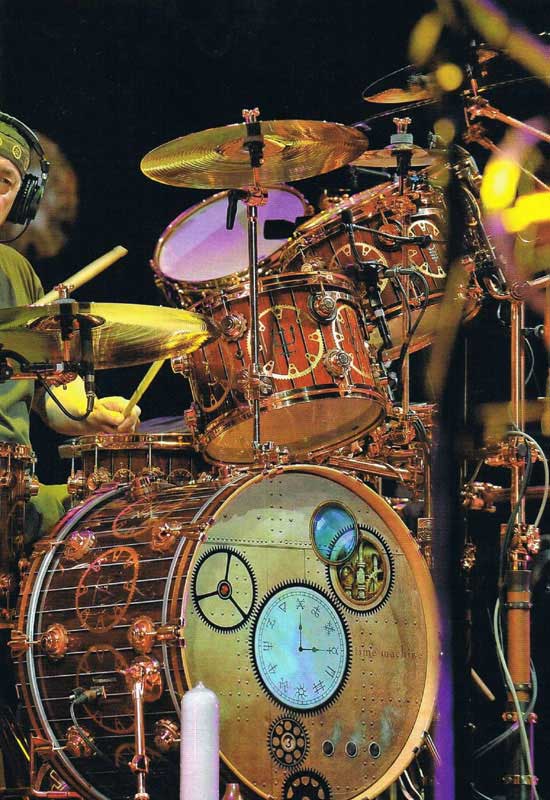

Yes, everything is all about the drumset for me, in several ways. The 'line on the riser' was drawn clearly for me in the '80s, when I first started experimenting with electronics. I realised right away that they would have to be 'satellites' around the main kit, and would never replace a single one of my acoustic drums or cymbals, just augment them.

(That is what led me to the rear kit, and the rotating riser, around 1984.)

This solo absolutely focuses on the voices and traditions of acoustic drums. The electronic effects only add atmosphere, or unusual sound textures. And, even those are all still played by me, on a V-drum or Dauz pad, the MalletKat, or Kat foot trigger. Every sound you hear originates with a stick or a pedal, randomly triggered at will.

Over the past few years, improvisation has been a major aspiration for me, both in creating drum parts for songs, and in soloing. In that spirit, this solo was approached without any plan other than the above theme: traditional solo with 'extras'. I would simply launch into it from the song, and let the dynamics rise or fall into whatever 'frame' next occurred to me. I don't think I even consented to attempt it until the final few rehearsals, determined to keep it as fresh as possible. I just demonstrated the cue to come back in to Alex and Geddy, and the rest would be... a mystery.

(Lighting director Howard was disconcerted by that - accustomed to my usual 'composed' solos, where he could program fixed cues for lighting changes. But if I could wing it, I figured he could!)

Right away I loved building out of the triplet-feel snare fill in the instrumental (thank you Terry Bozzio, who in turn thanks Tony Williams!). I sometimes held that jagged, tension-building pattern as long as mind, hands, and feet could keep it together. Riffing out from there, that fill dictates the initial feel and tempo, and after that, I just let myself go.

That felt dangerous at first, all right, but that's what I wanted. ('Danger is my middle name' - well, actually Ellwood is, but never mind about that!) I wouldn't have attempted that even five years ago, but I hoped experience would be my guide. Not just experience in playing solos, it is important to relate, but experience in listening to them.

It didn't hurt that my first inspiration to play drums was the movie The Gene Krupa Story, in which the man himself performed so wonderfully, and was even pretty well 'lip-synced' by actor Sal Mineo. In retrospect, I could hardly have chosen a better starting point.

I count myself lucky to have learned to play in the mid-'60s, and - of all places - in Southern Ontario. It is true that compared to now, it was hard to 'see' live music (rare on television, and no instructional DVDs, websites, or apps). However, on the plus side, there were so many bands around in that time and place, and they were remarkably 'musicianly'. (Seems the only word.) Pretty well every drummer performed a solo, and I noticed some things. There were drummers I liked a lot when they played with their bands, but not on their own. They would have the technique, all right, but, I realise now, no sense of phrasing, structure, dynamics, tension and release, or telling a story. All I knew at the time was that while I admired their drumming, I didn't enjoy their solos.

Other soloists of the time were brilliant and inspirational. Two unforgettable Canadian examples were Skip Prokop with Lighthouse, and Jerry Mercer with Mashmakhan. Skip was a brilliant technician - a champion rudimental drummer, I recall - and delivered a superbly musical solo, while Jerry's live solo in 'Letter From Zambia' had all the primal power and drama the title suggests, and seemed to tell a story. Decades later, their influence remains in my ideal of what a solo ought to be.

My only other exposure to real rock music (as opposed to radio pop) in that primitive time was records, and Ginger Baker certainly opened the floodgates with 'Toad' - the vehicle for my own first solos. Other worthy recorded solos from rock drummers of the time were Carmine Appice with Vanilla Fudge, Peter Rivera with Rare Earth, and Michael Shrieve with Santana. (Woodstock, of course.)

Then there was The Tonight Show and Buddy Rich's many appearances. Well... I freely confess that back then I couldn't even understand what Buddy was doing - it was way over my head. But I certainly felt something like Louie Bellson once said, 'There are all the great drummers in the world - and then there's Buddy.' I did not ever expect to attain that level of mastery. Still don't...

It occurs to me that the movements of the 'Here It Is!' solo actually came to represent something of a drumming autobiography. I don't think it's too much of a stretch to say that drum soloing, at its best, is a kind of storytelling.

I learned that very vividly at one point in my life, as recounted in my book Ghost Rider. After a long, difficult period in which I hadn't played the drums at all for about two years, I arranged to have a quiet, private place where I would be able just to sit down and play. (Not to see if I could -to see if I wanted to.) As I got going, just riffing in what I thought was an aimless fashion, I realised I was telling my story. Thinking back over the patterns and moods I had wandered through, I thought, 'This is that part, and that was that part,' and so on. It was a remarkable insight, and helped me become 'reinspired' on the instrument.

In analyzing my solo from the R-30 Tour (2004) for the instructional DVD Taking Center Stage, I discovered that it actually had a chronology to its story - roughly the history of drumming from Africa and Europe, and where they combined into American music. Even the big-band finale seemed a fitting conclusion to that 'history'. I had not planned that structure for the story, but something was going on subconsciously, I have to believe.

In the 'Here It Is!' solo, the 'chapters' have their own stories to tell. Right off the top, I have loved the opening motif of freestyle snare work over driving bass drum since I was a kid, and it still 'works' for me.

And here's a profound axiom I will offer for free: 'In drum soloing, what is exciting to play has a good chance of being exciting to listen to.'

That is a deep observation. In more recent drumming explorations, the ostinatos are a big part of my storytelling technique. Max Roach's 'The Drum Also Waltzes' has served me for practice and improvisational soloing for about 20 years, while the Brazilian xaxado ("shashadoe") rhythm is a more recent fascination - only attempted in the past two or three years. It took a long time to get 'free' over the waltz time, but now I can flail around at will, in any tempo or time signature. I'm not there yet with the xaxado, but am happily working on it.

ALL ABOUT THE DRUMSET

Here is another way in which it's 'all about the drumset' for me. In the late '70s and into the '80s, whenever I dabbled with keyboard percussion or - in the '90s - hand drums, and thought of getting serious, I would reach an automatic turning point. Realising the dedication it would take to try to master those instruments, I would 'retreat' to the drumset. Because musically, that mix of four-limbed expressions already represents a lifetime of study, and of rewards. Glad to say that after 48 years of devotion to the drumset, it remains completely fulfilling - challenging and exciting - for me.

For example, when our year-long Clockwork Angels Tour ended recently, I was happy to lay aside the sticks for a while. For the past 10 years or so, my bandmates and I have been on a near-constant cycle of touring and recording, and during that time, I never thought about having drums at home. (It is especially complicated living in Southern California, where basements are rare, so you have to get very elaborate not to be 'anti-social'.) Whenever I needed to rehearse for a tour, the Drum Channel studio was only an hour up the Pacific Coast Highway. Sometimes, on a longer break, I even went there just to play for the fun of it. Not rehearsing, performing, or recording, just freeing my mind and body to express whatever emerged.

This October, barely two months into my self-styled 'sabbatical' from drumming and lyric-writing, my friends at Drum Workshop invited me up to the factory to try out some new shells, and I jumped at it. Once again, an opportunity just to play.

(During the hour's drive up there, I also laughed at myself for having a lyrical idea. 'You're not supposed to be doing that yet!')

Returning to the 'Here It Is!' solo, the 'floating' snare section of delicate rudiments is also a longtime personal favourite. (It occurs to me that it is played not to a tempo, but to a pulse.) Then, laying down a rapid single-stroke on the snare, I bring up the bass drum and hi-hat for the Brazilian xaxado ostinato. Again, the delivery of that section changes radically from night to night, often introducing new figures worked out on my warm-up kit before the show.

Sometimes that would resolve into jagged, staccato phrases, with double-pedal triplets and odd syncopations. Other times I would resolve with another device going back to my earliest solos, the double-hand crossover between the snare and floor tom. (Inspired by my first teacher, Don George, who once told me that those and four-way independence would be my hardest challenges. He wasn't wrong.)

Like the previous passages, those are never easy, and each of those sections could vary greatly from night to night - depending on my oh-so-human peaks and valleys, mentally and physically. As Somerset Maugham said, "Only a mediocre man is always at his best."

Best of all is when the phrases flow out - never effortlessly, but when my labour is repaid by my own excitement about what I am 'getting at'.

I repeat, 'In soloing, what is exciting to play has a good chance of being exciting to listen to.'

Next month: Neil breaks down another Clockwork Angels solo and considers the drum solo's future.

Part 2

In part 2 of his insightful exploration of drum soloing, Neil Peart breaks down another of his Rush solos, reveals his soloing influences and considers the future of the drum solo

This month, I will refer specifically to the arrangement that I happened to deliver on the night the DVD was filmed [Rush's new DVD, Clockwork Angels Tour]. In the tour's progress, these elements often appeared in different orders (listening back to this rendition now, I am gratified that the entire solo evolved a great deal during the remaining 40-or-so shows of the tour), but for our purposes, we'll consider this 'the one.'

By the time I had performed that solo a few dozen times, a natural series of 'movements' emerged from that free approach - a dynamic arrangement that seemed 'right.' I did not resist that evolution. It remained true to the spirit of improvisation, as each element within the movements was deliberately not allowed to become fixed. For example, when I went to the snares-off section over the waltz-time, I would be careful to begin the torn work in different areas of the kit every night. In every section of the solo, I would aim to keep transitions into and out of every pattern that might repeat as varied as I could.

An ending to a story, or a drum solo, is key, but at first I let that just 'happen' as well. Eventually it became clear that the flurry of hands and feet with cymbal accents was the ultimate climax - for me, and for the audience.

The axiom might be, 'If nothing works better, go with it.' (Even a drummer can sometimes see a no-brainer.)

However, it brings up a critical point. Like that climax, in other sections I would sometimes stumble across a rhythmic pattern that really excited the audience, and I would hear and feel their response. I liked that it happened naturally, but just on principle, to preserve that spirit, I refused to let it become a 'device'. It might seem irresistible to return to that pattern again, but not every night, and never the same way.

Some might feel there is nothing wrong with stringing together a series of such 'devices' (not to say 'tricks') that always work for the audience - you're supposed to be entertaining them, after all - and some performers would be happy with that result. Such methods are obviously how the formulaic arrangements of pop and country songs are assembled. But that seems to me a shallow pursuit. As my bandmate Geddy once said about the idea of songs having 'hooks', 'We are not trying to catch fish.'

And that, duh, is why drum solos almost never appear in pop and country concerts. Not 'part of the formula'. And notice that modern pop songs almost never have a single real drum in them, yet in concert, they always have a real drummer. For the dynamics, the excitement, the action of it all. They still need us.

Me, I want to tell a story, not just perform a schtick, so I have to be careful about those tricks. Some of them are just fun, like the stick tosses, and don't affect the music, or the 'purity of intent'. That's what has to be guarded.

Funny thing about the stick-throwing. I heard of such juggling feats as a kid, told about big-band drummers like Sonny Payne. A good story about Buddy Rich, who loved Sonny (he called him 'Funny' Payne), watching him play in the Count Basie band with my late teacher Freddie Gruber. As Sonny twirled and tossed sticks around and caught them, Buddy leaned over to Freddie and growled, 'He better be careful - he might hit something.' I also heard that the Rascals' drummer Dino Danelli performed such tricks, but I never saw it done.

When Golden Earring opened for us in the early '80s, I saw Cesar Zuiderwijk doing it, and thought it was cool. So immediately (and shamelessly), I started copying him. It was simply fun to try to do, and always risky. At best, after 30 years, I manage to catch nine out of 10, but still, some of them just 'get away'. When the stick is in the air, the audience seems to share the tension with me: "Will he catch it?" If I do, they are as relieved as I am.

I always used to think there must be some trick to it, like jugglers and magicians have, and that probably guys like Sonny Payne could do it perfectly every time. Then Terry Bozzio directed me to a wonderful film of the Basie band playing in Sweden, and Sonny was dropping sticks all over the place. But oh, when he "hit something" - then it was sweet perfection.

'THE PERCUSSOR (I) - BINARY LOVE SONG (II) - STEAMBANGER'S BALL'

Less 'drumistic' and much more about melodic percussion - atmospheric, cinematic, classical, other-worldly, hints of sci-fi and computer games... Hand-to-hand 16ths, but triggering melodic runs, sequences, combined with percussive shaker, hi-hat type sounds.

The main title 'The Percussor' derives from the novelisation of the Clockwork Angels story. Author Kevin J Anderson envisioned a clockwork drummer - 'The Percussor' - that began a hypnotic performance, then dropped a stick, and flew to pieces. (That was one of the few scenes in the novel I contributed to directly - I could relate!)

The subtitle, 'Binary Love Theme', comes from my motorcycle-riding partner, Michael, who is a computer geek who likes to try to insult me. (And those are his good qualities.)

During my pre-tour rehearsals, drum tech Lorne 'Gump' Wheaton put up a set of the new generation of V-Drums beside my main kit. Between bashes on the 'real' drums, I would experiment with their capabilities. A number of the programmed drumsets, from traditional to unearthly, were fun to play with, but I kept coming back to this one, 'Melodious'. I could play on it for hours.

As with previously-described electronic effects, every note in this solo is played. The difference is that on some of the pads (hi-hat, snare, ride, cymbal and bell), each strike would be a different note in an arpeggio. The crash cymbals were sustained minor chords, while other pads triggered percussion samples. The four toms were fixed piano notes, which I asked Jim Burgess to modify - adding a slight delay, so they were more like plucked harp notes. Playing on my 'back kit' for this, I could still reach some of the acoustic kit, like floor toms, piccolo snare, and cowbells, and they are incorporated into these pieces.

The 'Binary Love Theme' steps through a series of movements, everything improvised, or grown out of improvisation. The basic progression on this example is from waltz to 4/4, then to 7/8, but I even played with that juxtaposition from night to night.

Incidentally, quite a lot of paradiddle sticking is employed to achieve certain combinations of rhythm and melody. A reminder to practise those rudiments.

Second section with rhythmic ostinato and cowbells, 'block' sounds and other-worldly hits - steampunk effects - into xaxado (but electro) bass drum again... so melodic but still driving...

For this Jim Burgess and I selected an array of 'pre-electronic' industrial sounds. Metal sheets and iron boilers, steam release valves, anvils, sledgehammers, white noise, and sonar blips. Improvised patterns build to a repeating theme, which cues the video operator, Dave Davidian, to start the accompanying 'Percussor' film.

That is not 'done to click', but is a cooperation between Dave and me - his timing, and my tempo control, you might say.

As a general thing, I use very few 'click' cues in our live show - and then only for sequenced passages that are too legato or vague to keep in sync with, and sometimes for the sake of the string players. (Holding together 11 musicians is exponentially more complicated than when we are just three!)

At the end, where the Percussor goes to pieces, I try to portray that with a 'deconstruction' of the pattern, then end with a couple of steam-train whistles. Because... well, just because...

The Future Of The Solo

Finally, I have been asked about the 'future' of the drum solo. As mentioned, these days it is absent from the 'mainstream' of popular music, but I would venture that has been so since the dawn of recorded music. Jazz has always embraced self-expression, freedom, and virtuosity, and that has not changed. Some rock musicians have also aspired to those values, but in the final analysis, it is up to the audience.

The popularity of more adventurous music ebbs and flows, but does seem to endure. Perhaps in these times even the word 'progressive' has evolved from admired, to despised, to mildly respected.

Certainly it has always been true that drum solos are more exciting in concert than on record. Again, drummers have a visual thing going on - what is nowadays called 'optics'. If it is left up to the audience, I believe drum solos will endure.

Because for almost a hundred years now, through countless style changes in hair, clothes, and music, people have been excited by a drummer playing something that excites him or her.

It's in our very cells. Usually...

"But before Alice could answer him, the drums began. Where the noise came from, she couldn't make out: the air seemed full of it, and it rang through and through her head till she felt quite deafened. She started to her feet and sprang across the little brook in her terror, and had just time to see the Lion and the Unicorn rise to their feet, with angry looks at being interrupted in their feast, before she dropped to her knees, and put her hands over her ears, vainly trying to shut out the dreadful uproar.

"If THAT doesn't "drum them out of town", she thought to herself, 'nothing ever will!'" (From Through the Looking Glass, by Lewis Carroll.)

12 Essential Drum Albums

By Jason Bittner

With 'Shadows Fall', Jason has built a reputation as one of metal's finest players. Here he breaks down his most influential albums

#1 Rush Exit...Stage Left (1981)

"The reason I picked Exit...Stage Left is because it's impossible to pick just one Rush studio album. Rush are my favourite band, and Neil Peart is my favourite drummer. I can't possibly sum up the band in one record, but I can say that Exit... epitomises a period in time when Neil was most influential in my life.

"When I was a freshman and sophomore in high school, I would come home every day and play along to this record - at least to the best of my ability. I set drums up so they were just like Neil's, having everything as exact as I could - the same everything. It was that important to me. I could go on about how awesome the record is. The drum solo is still one of my favourites ever. It's definitely my favourite Peart solo. The drum sound on the record is amazing, too, which is saying something because sometimes the sound on live records can be lacking. Okay, if I had to pick a favourite Rush studio album it'd be Moving Pictures - a brilliant album all the way around."