Neil Peart's News, Weather and Sports

Science Island

NeilPeart.net, October 6, 2014

For thirty-four years, over half my life, I have spent time nearly every summer and winter in the Laurentian Mountains of Quebec. It is a region I call my "soulscape," sapphire lakes set among emerald mountains in summer, diamond dust in winter. The thick second-growth woods are rooted among ancient, worn-down peaks, some of the oldest rocks on Earth. Once Himalayan-sized mountains, a series of massive glaciers chewed them down and gouged out the lakes and valleys, flooding them with meltwater.

In these more recent times-say the last twenty-four years-my sanctuary has been on Lac St. Brutus, my favorite place in the world. The lake has four major islands, each about an acre in size, and because they are inaccessible for half the year, none has been built upon. For fifteen years I owned one of them, l'Île Selena, but sold it with my previous house and land when I briefly contemplated moving my retreat to Ontario. (Until my then-new wife Carrie visited, loved the area, and said, "Are you sure you want to leave here?" Which makes a guy go, "Hmm...")

Rich memories endure of my early days on that lake, before I even started to build a house there. Owning a stretch of wooded shoreline and an island with no buildings means no responsibilities-no expenses, no problems, no worries. Just playtime. I kept a battered old rowboat inverted onshore, and would row out to the island with our white Samoyed, Nikki (for Nikita), and a load of camping gear. For the rest of the day Nikki lounged contentedly on a shady pine-needle bed, sniffing the various aromas of lake and woods, while I cleared trails and burned deadfall in the big firepit. In the evening I poured a measure of the Macallan and sat awhile, then rose to prepare a campstove dinner-some dreadful mix of dehydrated noodles, powdered sauce, and canned fish (known to backpackers as "tuna wiggle"). The humble repast was elevated nicely by a good red wine, and an old-school percolator of dark coffee. After such an active day, I soon crawled into my little tent. It had a covered portico that just fit a curled-up Nikki, and he loved being out there with me, of course. The nights were especially magical-all stars and loons and woodsmoke. I miss that island, and sometimes think about trying to buy it back, or maybe better, one of the others-to continue the "starting over" theme.

|

Eagle Rock |

Near the wooded, boulder-studded shores of those four islands, a few tiny islets of rock stand above the water here and there. One of them has a steep cliff into deep water that was always fun for a gang of us to jump off of. Twenty-four years ago just one solitary fir tree grew on its crown, so it became known as l'Île de Noël. (Christmas tree, see.) One neighboring couple told me that in the early years, before there were many houses, an unnamed couple once made the beast with two backs there. So they called it l'Île d'Amour. A large granite stone, an "erratic block" (meaning dropped by a retreating glacier), on top of it suggested the shape of an eagle's head to this bird-brain, so our family called it Eagle Rock. With a young boy's natural reductiveness, Brutus's son Sam called it Rock-on-Top-of-Rock.

That is a lot of names for a little bump of rock, and yet another was bestowed upon it in the summer of 2014-Science Island. For all of August (the heart of summer, just as February is the heart of winter) I was fortunate to be at the lake, with Carrie and Olivia joining me for two weeks in the middle. (Leaving a solitary "reading week" on each side-hurray!) Nearly every day, five-year-old Olivia and I liked to venture out on the lake in our small electric boat, or in my sleek rowboat, and we often stopped at that little island. While pulling the boat up on the rocky shore, I showed Olivia the parallel grooves in the rock's surface that had been left by glaciers. I explained how the tremendous mass of ice had dragged stones along and gouged out those grooves as the glacier retreated, at a speed of maybe an inch a year. Then I pointed upward as I told her the ice was once about two miles high above us.

She looked at me with that wonderful guilelessness of childhood (when does that go? About eight, maybe?) and said with a wide-open smile, "Was that before you were born?"

I assured her it was.

She pointed down at the pale green patches on the rocks and asked me what they were. I told her they were lichen, a primitive plant similar to the moss that carpeted the ground between the exposed rocks.

"They live off the stone itself," I explained, "from its moisture and minerals."

I thought of the old generality about "the nature of things," and pointed around us at the wooded shores as I said, "Everything we see is either animal, vegetable, or mineral."

She thought about that, then fastened on a natural objection. She pointed to the lake and said, "What about water?"

Ah, she had me there for a moment-but then I realized (with a little relief), water is assuredly mineral.

Growing up in California, Olivia has been raised to be conscious of water use-she explains solemnly, "because of the drought." I told her that in Quebec we didn't have to worry about that, which led to explanations of the water cycle of evaporation and rainfall that kept our woods green and thriving, and our lake full of clean, cold water. We talked about clouds, winds, rain, snow, the little stream that runs through our land and swells after rainstorms, fog and dew and rainbows.

While drawing and coloring one day, we talked about the proper order of colors in a rainbow. I had always used a sequence that seemed good to me, while Olivia had her own preference. We decided to see what Science said. Olivia has great respect for science, especially the natural branches, and is proud when her mother calls her "my little scientist." (That will be helpful for her adult ambitions: to be a doctor, an astronaut, and a construction worker.) An internet search taught us the mnemonic ROY G BIV for the correct order. Red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet. Lovely.

|

Riding Loonie-Back |

One of the oft-celebrated delights of northern lakes is the calls of loons. In our area, each lake has a resident pair that returns year after year. Their vocal tremolos are familiar in movie and TV soundtracks, and even in pop music. In the late '80s I came back from a bicycle tour in West Africa with a cassette by a popular reggae artist from Côte d'Ivoire (Ivory Coast), Alpha Blondy. The technology for sampling sounds and playing them with keyboard or drum triggers was new then, and I smiled at how Mr. Blondy was obviously very taken with samples of loon calls. He would never have heard the real thing in West Africa, but for anyone among us Nordic peoples who has, it is an unforgettable experience. Their various songs are eerie, unearthly, and endlessly haunting, especially on moonlit nights, when they can fish and move around the lake, calling to each other. Olivia and I had been seeing "our" pair of loons often, with their new baby chick. That is always an exciting event on the lake, because loon nests often fail due to a rising or falling waterline, or predators.

Most birds have hollow bones, but those of loons, one of the most ancient of species, are solid and heavy. That weight is helpful for diving deep in search of fishy food, but not for getting airborne-loons require a long laborious taxi across the water. Their feet are far back on their bodies, likewise good for swimming underwater (they also use their wings), but they cannot walk. The nest has to be right at the water's edge, where they can push themselves onto it. If the water falls, they won't be able to get to the nest; if it rises, the eggs float away.

While rowing around the lake one day, Olivia and I heard the adults call to each other across the lake with their "I'm over here!" three-note yodel. We saw the baby loon swimming beside one of its parents, then dive under and come up in a different spot. I told Olivia I thought it was the first day the baby loon had ever done that, and she called out, "Congratulations baby loon!"

(Obviously a triumph another child would relate to!)

|

Loon and Chick |

One time we saw a family of ducks called mergansers swim by, a mother and four youngsters hugging the rocks and trees of the shoreline. Not wanting to romanticize the natural world, I tried to tell Olivia delicately that they usually stayed safely close to shore like that because given the chance the loons would kill the babies. (I didn't get too graphic-didn't add that the loons swim up under the baby ducks and stab them with their dagger bills.) I offered the explanation that this seemingly murderous impulse was actually for "love"-intended to protect the loons' own babies from other fish-eating competitors.

Loons typically incubate two eggs, but usually only one will survive (stacked odds, because they are laid a day apart and hatch that way, so the older chick bullies the younger one until the parents ignore it and concentrate on the one that appears stronger-more likely to survive). Both male and female loons care for the eggs and young, while mergansers are different-I have never even seen a male merganser. The flamboyantly colored males only hang around for mating season in early spring, then after the ten-to-twelve ducklings are hatched, they take off farther north to moult (so they claim... the females probably think, "how convenient"). The female mergansers make up for being single parents by helping each other-I have often seen as many as thirty youngsters trailing after one mother, who is babysitting for the day.

So, with all that talk about geology, meteorology, and biology, one day when we were rowing home, Olivia said, "We should call that place Science Island."

I said, "Yes. I like it! From now on that is its name."

|

Little Pink Butterfly Hood |

Olivia turned five on August 12, and that spring her mother had signed her up for biweekly swimming lessons, so she was now a strong swimmer. No more life-jacket or water-wings for her-just foam noodles for fun. Swimming "free" like that opened a whole new world of enjoying life at the lake, for both of us. (Second time around for me, of course-it's becoming ever more difficult not to talk to Olivia about her lost sister, especially when we boat past the old house, or the island still named for Selena-she would have turned thirty-six that April. So many stories about Selena that I know Olivia would love. But I also know I have to wait until she's better able to comprehend such world-shattering information. Maybe when she's eight or so. I guess I'll know-but it will be hard.) Olivia and I had a good time on the lake and in the lake nearly every day, and one hot day we went swimming four separate times.

On a cool morning when dark clouds threatened rain, we put on our rain jackets and reef shoes and walked down the gravel road to our neighbor's house. We picked up a food container we had left there while visiting a few days before, and on the way back, I led us through the woods. I assured Olivia, "There used to be a trail here." However, that had been fifteen years before, and it was largely overgrown-we had to do some serious bushwhacking. Olivia never faltered-just followed me through the trees, rocks, roots, and moss, pushing her way through the branches in her pink and purple butterfly raincoat. No complaints, no moans, no sighs-because we were sharing an adventure, not an ordeal. Just as last winter she was the Merida (Scottish princess in Disney movie Brave) of snowshoes, now she was the Merida of the summer woods.

When we finally fought through to the shore, I helped her across the stepping stones over the little stream, and we emerged at our dock. I told her I was proud of her, and she said, "Me too!"

|

Misty Morning |

Rowing had long been a favorite summer exercise for me, and I had owned the boat pictured here, with sliding seat and outrigger oars, for twenty-four years. Most every summer day I went for a long row around the lake, feeling the satisfaction of driving my whole body into the oars as the nimble hull sliced through the water. However, I had always dreamed of having a real racing shell...

One night a heavy rain hammered down on our metal roof (wonderful sound-nature's drum solo) for hours, and in the morning Olivia and I went down to the dock to bail out the boats. While sitting on the rowboat's wooden seat, I leaned toward the stern with the bailing cup and heard a "snap"-the seat had broken in half. Fortunately enough of it remained for me to keep up my daily rowing routine, at least in a half-assed fashion-which was not much of a change. (Badaboom.) An internet search for a new wooden seat came up empty, but did lead me to the sites of several builders of racing shells. A spark lit up in my brain. "Yes," I thought, "now's the time."

For some reason that summer, after all those years of "recreational" rowing, I rose to a new level of engagement. I reveled in the feeling while I was doing it, putting all of my strength through my back, arms, and legs into that rhythmic motion, and I loved how I felt after-unlike cross-country skiing or snowshoeing (or drumming), there was no pain, just an all-over sense of well-being. Which is why we exercise, right?

So I chose a builder who offered an old-school look with mahogany veneer over the hull, but included modern carbon-fiber hardware and oars. I placed my order for delivery next spring-ready for another summer. It's going to be so great...

Similar to cross-country skiing, the flowing rhythm of rowing is a subtle combination of many small cogs, levers, and energy sources. With much practice, they are refined into clockwork synchrony, until you don't even have to think-each part of the body knows its job. When I decided I wanted to write about rowing, I tried to pay attention to each of those elements, and mentally put them in words.

Breathe in deeply while the body slides the seat sternward, wrists twisted to "feather" the oars (to flatten the blades and cut wind resistance). Arms extend to reach the oars forward-then twist the wrists and pull up to angle the blades just into the water, to make the "catch." Begin to exhale as you uncoil through the shoulders, arms, trunk, and legs. Feet press hard against the footrests as the leg muscles extend, sliding you back on the seat as you pull through the whole body to drive the boat forward.

The wake surges for a moment with the propulsion, and the next time the oars meet the water a satisfying distance has been covered from the previous circles of ripples. At the end of the stroke, curve the oar blades back to feather position, keep your legs flat for a second, out of the way of your hands as you pull the handles close in to your body then start to extend them again. The handles must be low so the blades are high-not to touch the water and "catch a crab"-and staggered just the right amount, one above the other, so they don't knock together. (The rubber covers on my old handles are battle-scarred from early trial-and-error days.)

Take a deep breath and repeat, repeat, repeat...

After a long row, I return to the dock well heated up, especially on sunny days. Once the boat is tidily lashed to the whiplines, I shed my clothes, don my goggles, and ease into the water. There is an old wooden dock farther down the shore that is never visited-no house was ever built on the lot. It is about a quarter mile away, so a perfect target to swim to and back. Easing into the front crawl's natural flow, I breathe on alternate sides, every third stroke (called "bilateral breathing"), a technique I learned long ago from the late Mike McLoughlin.

Mike was a longtime member of our touring family, starting our first merchandising operation in the late '70s (a business continued today by his son Patrick). Back then Mike was an open-water swimming enthusiast, and on days off would go offshore in places like San Francisco Bay. When I first became interested in distance swimming, in the 1980s, Mike explained that if I started out trying that three-stroke rhythm on the front crawl I would be able to develop it, but it was very difficult to adopt later. The stamina and breath control I had built through drumming helped me to master the technique, just as they aided with long-distance cycling, cross-country skiing, and rowing.

Coming up alternately on opposite sides of your body to breathe seems clearly superior, but I notice that when I'm at the Y and using the cross-training machines, which overlook the pool, I very rarely see anyone going three strokes between breaths-always two, on the same side.

(And when I'm on those machines, or in that pool, don't I wish I was really cross-country skiing, or rowing, or swimming in that beautiful lake?)

Distance swimming rewards the same economy of motion and smooth full-body technique as does rowing or cross-country skiing. (Or drumming.) I was pleased that Craiggie captured the particular moment shown above-not just the picturesque splash as I kicked, but my arm emerging from the water in a relaxed curve, the wrist bent and doing no "work" until it has to. Just that trailing wrist demonstrates a general principle that applies to every sport that requires rhythmic stamina. (It is certainly a principle espoused by my late drumming teacher, Freddie Gruber. "If the stick wants to fall, let it fall. If the stick wants to bounce, let it bounce.")

Which brings us naturally enough (for the fourth time) to a topic I haven't given much "coverage" to lately: drumming.

While I was at the lake by myself for the first week, I was happy to be invited to the home of my neighbors (a few lakes away) Paul Northfield and Judy Smith. Their little house on Lac Cochon is elegant and comfortable, good taste evident in art, lighting and music, and they are both fine cooks. Paul and Judy also have long associations with the place that first brought me to the Laurentians-nearby Le Studio, where the Guys at Work and I recorded at various times from 1979 until 1995.

Paul was the engineer on many of those sessions, from Permanent Waves right up to Vapor Trails in 2001 (though recorded in Toronto), on the Buddy Rich tributes he and I recorded in the early '90s, and on my second instructional DVD, Anatomy of a Drum Solo. Judy had been with Paul all through those years, and had managed Le Studio for five years in the mid-'90s. And of course they had known my "first family" all through that era. So we go back.

That night the subject of Le Studio's abandonment and ruination came up, and the very next day I had an email from Meghan at our office asking me to do an interview for the guys at Banger Films (makers of the Beyond the Lighted Stage documentary). They were making a show about one of the Guys at Work, Geddy, and wanted to talk to me.

It was immediately obvious where that interview had to take place.

A few days later, on a pleasantly cool and overcast afternoon, I put the top down on the Z8 (Zed 8, when it's in Canada) and took the short drive to meet the Banger crew. The route was what I think of as back-back roads, mainly gravel, and in one way it might seem a shame to subject a beautiful car to all that dust and flying stones-but in reality it was absolutely the right thing to do. Another one of those times when I hear "On Days Like These" on my inner radio. I pulled up in that familiar driveway for the first time in about fifteen years (hearing that it was abandoned and crumbling, I had never gone back to look).

At the moment of arriving, and even on the way there, I felt some emotions bubbling up, but I kind of pushed them down for the moment-unsure exactly what I was feeling, or would feel. Later I realized that the experience was really just too much to process all at once-because no other place on Earth had been more important in my life. So that's big.

Glancing back at all the days and nights, the weeks and months, the summers and winters, the songs, the albums, the laughs-it was a long emotional parade of memories. Yet at least the ghosts there were happy ones, so it was enjoyable to wander among them.

Our first visit to Le Studio was in the fall of 1979, to record the basic tracks for Permanent Waves. After making the previous two albums, A Farewell to Kings and Hemispheres, in rural Wales and London, it was great to find a place we loved that was only a six-hour drive from our homes.

(Still remember my first drive up there, at such a beautiful time of the year. I was in the black Mercedes 6.9 sedan I had bought in 1978, just after Selena was born, as my idea of a "family car." What a crazy big muscle car that was-one of the few in my multi-car life I wish I'd kept.)

|

Le Studio 2014: A Farewell to Things |

In subsequent years we returned to record and mix Moving Pictures, then to mix a live album, Exit: Stage Left. There wasn't much for us to do on that project except occasionally approve performances and balances, so we started messing around with other things. Alex built and crashed radio-control float planes; Geddy learned everything in the world about baseball (his new passion then), and I did a painstaking nut-and-lug restoration of an old set of Hayman drums that were laying around the studio basement. Apparently they had belonged to Corky Laing, drummer with Mountain, and I liked the way they sounded. Each of us eventually started fooling around with our instruments, and wrote "Subdivisions"-I remember the Guys at Work coming up to me in the driveway of the guest house while I was polishing my Ferrari 308 GTS (black over red; lovely car) and playing the demo for me on a cassette player. (I played those Haymans on the demo we recorded.)

In the summer of 1982 we returned to record that song properly, and to put together the rest of that Signals album. During those Signals sessions, the Tama drum company asked for a portrait of my new kit. (The shell design of those prototype "Artstar" drums, in candy apple red, was inspired by the Haymans-I asked Tama to replicate their relatively thin shells, because I liked the way they resonated.) I dreamed up the idea of doing a photo shoot in the middle of the lake-setting up the drums on a swimming raft that was moored offshore from the studio. With our band crew and the studio guys helping, each piece of the four drum boards on which the stands were mounted was ferried out by rowboat, followed by each of the drums and cymbals. I canoed out there, then sat and played while microphones were recording from shore (interesting experiment, but never used for anything). Art director Hugh Syme and photographer Deborah Samuel floated around me in a pedal-boat while Deborah snapped away, and the resulting image was used by Tama on a large fabric advertising banner.

|

Rockin' It Forward |

That banner was popular with a younger generation of drummers coming of age in the '80s (because in that era of rampant drum machines, there weren't that many "real" drummers and drumsets to get excited about). My friend Taylor Hawkins told me he searched out one of those for himself not long ago, to honor a teenage fantasy-but that it now hangs on his son's wall. Nice-corrupting yet another generation!

Then, in the long winter of 1983-84, we struggled with the making of Grace Under Pressure. (One of our "trouble child" records.) From then on our visits to Le Studio became more sporadic-as we experimented with "settings" again, recording and mixing in the English countryside, in London, on the tropic isle of Montserrat in the Caribbean, and in Paris. (Because we could.) In the '90s we returned to Le Studio with Rupert Hine and Stephen W. Tayler to record the basic tracks for Presto, and with Peter Collins and Kevin "Caveman" Shirley for the same on Counterparts.

Around that same period, Paul Northfield and I recorded the Buddy Rich tribute albums in New York City, then brought them back to Le Studio to mix. Later that decade, starting in the summer of 1997, my world came crashing down piece by piece, like a bad country song ("My baby died, my lady died, my dog died-and my best friend went to jail"). During those "wilderness years" (see Ghost Rider), I did not pick up a pair of drumsticks for two years. In the summer of '99, I had an urge to quietly, privately see how I felt about drumming. Under another name (a covert operation-ha, "black ops"), I booked the little back room at Le Studio (called "The Far Side") for a couple of days. My local friend Trevor helped me sneak in my old yellow Gretsches, and I spent some time setting them up and tuning them. I sat behind them and picked up the sticks, curious to see if I could still play, really, and maybe how I felt about it.

What I found myself doing that day was playing my story. I thought I was just hitting things aimlessly, but suddenly I felt the narrative that was coming out of me-or maybe through me. "This is the angry part-this is the lost part-this is the journey."

It was kind of spooky.

So, to consider Le Studio at all was to consider a lot of my life that had been centered on that place, and so much of my best work. But it felt good to reflect on it all now, with pride, and relief that it was over. Because I wouldn't want to do any of that again.

Why?

|

The Door of Doom |

If this door could talk, it could tell you why...

It simply leads between the control room and the recording room-but sometimes those few steps represented a hard, painful journey. You would pass through it after listening to a playback, on your way out to try it "one more time." Or ten. Or a hundred. I will never forget the sound of that latch (made for a walk-in freezer, like in a slaughterhouse, I guess). As you pushed in on the round knob, the spring compressed with a dull rasp, the latch opened with a metal-against-metal swipe, and it ended with a hard, cold "snick."

In the days of Permanent Waves and Moving Pictures, for example, we would first have spent a few weeks at a country place in Ontario working on the songs. We arrived at Le Studio with some songs ready, some mapped out, and at least one yet to be written. So we ended up playing each of those songs many, many times, all of us in the room together-making a heck of a racket as we flailed through and worked out the arrangement, our parts, the interaction with the other guys' parts, sonic issues, and the overall performance. It was utter chaos, which made the constant repetition all the more necessary.

In recent years we have learned to do all that detail work separately, adding nuances to our own and each other's parts in a "leapfrog" fashion. Tweak the arrangement on a demo, add a sketch for the drum part, update the bass and guitar parts to suit, then redo the drums to raise the level of "action and interaction." This method allows for the more improvisational approach I prefer these days, but thirty years ago my drumming was more compositional-so the endless repetition served me well in creating those intricately detailed drum parts.

But it hurt. I do not "wish I could live it all again," but still, there are many, many good memories from those days.

|

"Right Over There..." |

As I stood in front of the low, weathered building with the Banger crew, I described the recording of the intro for "Witch Hunt" on those very steps. On a night in early winter, with a few snowflakes in the air, we set up a microphone outdoors and acted out the vigilante scene. The rabble-rouser was played by yours truly, shouting out stuff like, "We've got to stand up for law and order!" and "We have to protect our children!" The mob I was inciting to mayhem was made up of the Guys at Work-band, crew, and studio guys.

Another thirty-four-year-old memory emerged as I led the Banger camera and crew around to the back of the studio building, where the lake appeared through the trees. I described the recording of the intro for "Natural Science," down by the lakeshore. On a cold night late in 1979, Alex and I stood at the water's edge with rowboat oars and canoe paddles, stirring the water. A microphone on a stand beside us captured the sound effects for the "Tide Pools" section. (Considering all our experiments with sonic environments and music-making gadgetry-digital recording, electronic instruments, midi interfaces, digital sampling-that studio represented a kind of "Science Island," too.)

All these years later, after standing and looking out at that lake again, kind of overwhelmed by so many flashes of memory, I turned back toward the building. Shading the reflections with my arms, I looked through the plate-glass windows into the recording room and saw the parquet floor where my drums had been set up so many times-where I had "faced the music," and faced that curséd control room door.

|

"My Drums Were Set Up Just There" |

The studio building sits at one end of a small kidney-shaped lake; at the other end is the guest house-a large, multi-bedroomed dwelling, beautifully decorated by owner André Perry and his partner Yaël. Also apparently abandoned now, the guest house was augmented by a smaller building, "The Little House on the Driveway," usually shared by a couple of crew members. Commuting between there and the studio in summer, you could take a rowboat, canoe, or pedal-boat, or in winter, cross-country ski. On summer nights you could drift in a boat in the middle of the lake, in perfect silence and utter darkness, with the Milky Way seeming to loom down over you from overhead.

In the winter of 1980, when we were working on Moving Pictures, and a couple of years later for Grace Under Pressure, I made two "commuter" ski trails: one over the ice and snow around the lakeshore, and one through the woods, on land. I took the lake crossing in the daytime, or if there was someone with me. (Alex had a brief flirtation with cross-country skiing the first winter, when the late Robbie Whelan, then assistant engineer and invaluable member of the recording team [see "Not All Days Are Sundays"], taught us to ski. Fifteen years later Alex would take up motorcycling at the same time I did, then later give it up-he's fickle that way!) Alone at night, I took the "overland" route through the dark woods, with the parallel tracks in the snow faintly visible by moon or stars. Skis tended to follow those grooves easily enough, but I have never forgotten one snow-covered boulder in the woods that always, time after time, made me start and think "bear!" A momentary thrill of fear tricked me every time, just for that split second. Certainly we are all hard-wired to respond to stimuli like that-anything that looks or sounds like it might eat you.

|

Commuter Lanes |

In the early '80s we stayed in the guest house for long stretches, working at the studio for months at a time, refining songs and arrangements, recording tracks and overdubs, and mixing. We also played a lot of volleyball. We would stop work an hour before dinner and play, usually with enough guys for four or five on a side, and after work-starting at midnight or one a.m., and sometimes continuing until the light of dawn appeared. (In high summer at that latitude, the sky would start to pale about 4:30 a.m.) The uprights that supported the net were topped by a few floodlights on each side, to illuminate the playing area, more or less. An errant ball rolling off into the darkness could be a problem. As autumn brought down the leaves and then the snow, we would shovel the court every night, and keep playing as long as we could.

The following passage was written for a bio and tour-book essay for Presto, in 1990. (Funny that I first referred to the Guys at Work as "Rash" in that story-a joke that would recur over twenty years later, in comedic films to accompany the Time Machine tour.)

A long day's work behind us, we gathered outside, charged by the cool air of early summer in the Laurentians. We doused ourselves with bug repellent, then gathered on the floodlit grass, took our sides, and performed a kind of St. Vitus Dance to shake off the mosquitoes. Occasionally one of us hit the ball in the right direction-but not often. Mostly it was punched madly toward the lake, or missed completely, to trickle away into the dark and scary woods. ("That's okay; I'll get it.") We were as amused by Rupert's efforts at volleyball as he'd been by our songs, but indeed, all of us had our moments-laughter contributed more to the game than skill. And if the double-distilled French refreshments subtracted from our skill, they added to our laughter.

Between games the shout went up: "Drink!", and obediently we ran to the line of brandy glasses on the porch. Richard the Raccoon poked his masked face out from beneath the stairs, wanting to know what all the noise was about. "Richard!", we shouted, and the poor frightened beastie ran back under the steps, and we ran laughing back onto the court. The floodlights silvered the grass, an island of light set apart from the world, like a stage.

On this stage, however, we leave out the drive for excellence; no pressure from within, no expectations from others. Mistakes are not a curse, but a cause for laughter, and on this stage, the play's the thing-we can forget that we also have to work together.

Work together, play together, frighten small mammals together: Are we having fun yet? Yes, we are. And that, now that I think about it, is why we do what we do, and why we keep doing it. We have fun together. How boring it would be if we didn't. Not only that, but we work well together, too, balancing each other like a three-sided mirror, each reflecting a different view, but all moving down the road together. As the Zen farmer says, "Life is like the scissors-paper-stone game: None of the answers is always right, but each one sometimes is."

Those reflections from over two decades ago make a good segue to the part of the story the Banger guys wanted me to address: one of the Guys at Work, Geddy. Having said that Le Studio was the most important place in my life, it follows that the most important collaboration in my life has been with Geddy. That's all I really wanted to say on camera-though I don't think those actual words occurred to me until later.

In any case, the interviewer, Sam, had his eye on "the show" they were making. Naturally enough, he was looking for some incisive remarks from me, maybe some kind of "dirt"-if not blood. Preferably bad blood. He was careful about it, trying to bring me around to that sort of nitty-gritty by apologizing for "being like a three-year-old, asking the same question again and again." But a complex relationship that has endured for over forty years is not going to be defined in a sound bite. It's like asking a spouse of that duration to define the other-tread carefully!

I am often reminded of when Carrie and I were first getting to know each other, late in 1999. She had worked in human resources (loathsome name) for some big corporation, and asked me, "What do you think your friends would say is your worst flaw?"

My immediate answer was, "My friends wouldn't say anything bad about me!"

She said, "You're being evasive."

But honestly, I didn't think I was. I was simply puzzled, and even now can't imagine such a scenario.

Perhaps it represents yet another echo of the line from the song "Presto" that I often cite as being always-and-forever true, "What a fool I used to be."

Then, in talking about Geddy, Sam also wanted me to presume to analyze why the guy is the way he is. Oh no, no, no.

(Not entirely unconnected, the dawning insight expressed in "Magnetic Mirages" continues to swell into a paradigm shift in the way I look at other people and their behavior. "They can't help doing what they can't help doing.")

Now... certainly I don't want to diminish Alex's role in the music created lo, these many years, by the Guys at Work. After all, he is our Musical Scientist, the Funniest Man Alive, and a shamefully underrated and thoroughly wonderful guitar player. But the musical relationship between bass player and drummer, the rhythm section, is famously tight (or ought to be!). And of course the bond of trust necessary between lyricist and singer is even more intimate.

Posing in front of Le Studio that day in August 2014, I told the camera that as bass player and drummer, the communication between Geddy and me operated on three levels: 1) auditory, when we listen to what each other is playing and respond to the ideas, accents, and patterns; 2) verbal, when we discuss different approaches we could take together and try them; and 3) something that verges on the telepathic, when suddenly we're both playing an interlocking pattern, onstage or in the studio, and laugh out loud.

I explained how the lyrics were completely subservient to their purpose-to be sung-and that if Geddy found something awkward to sing, I changed it. If he found something pleasurable to sing, I tried to write more like that!

Because surely the essence of collaboration is making each other happy, yes?

|

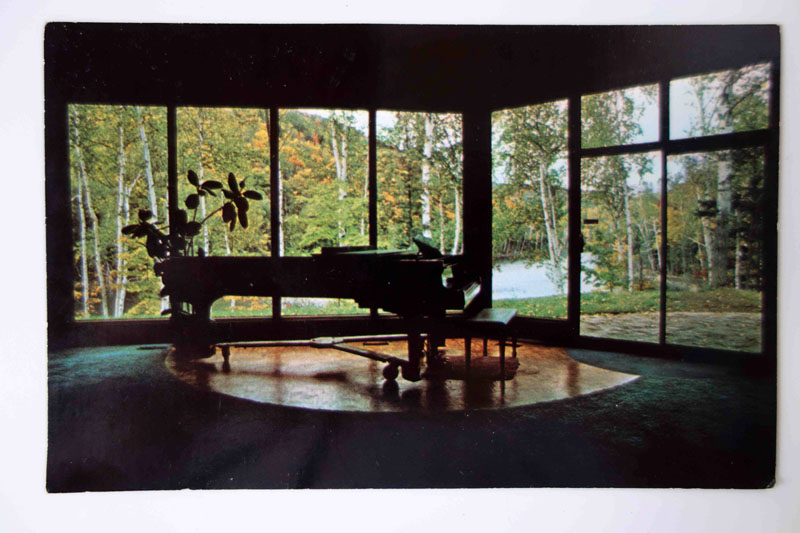

1970s Postcard |

This photograph is from almost forty years ago, and as of August 2014, that very piano sits among the ruins. Inexplicably, it has been left to moulder away in the summer's damp heat and the winter's brittle cold.

My feelings were running high during that visit, but I could not quite define them-words failed for a time. Some people described the place's abandonment as "sad," but wandering through those rooms did not make me feel that way. What I felt was more like lucky, and an overriding sense of gratitude-that we had been fortunate enough to live and work in a place like that, all those times, in every season. And others like it: Air Studios in the tropical paradise of Montserrat, the "quaint" British residential studios like Rockfield, the Manor, and Ridge Farm, and Bearsville and Allaire in New York's Catskill Mountains. In today's lean and hungry music industry-for better and worse-such facilities are all part of a vanished world. Certainly it will be a long time before a rock band will ever again enjoy and be nourished by such artistic and playful retreats.

That, to me, is the really sad part.

Because, see, we've all got enough unhappy ghosts, don't we? The world is full of them-even among the living. There's just so much anger everywhere, a growing epidemic that, as much as any plague, threatens our extinction.

|

Conjuring the Happy Ghosts |

Not long ago I read about a publication called CyberPsychology & Behavior analyzing people's disgraceful behavior behind the mask of the internet. Of course, in the tradition of psychology's desperate wish to be seen as a science, they had to give it a fancy new name: "online disinhibition effect." It describes the unsurprising insight that "people say and do things in cyberspace that they wouldn't ordinarily say and do in the face-to-face world."

Really.

I have drawn that comparison before about people in their automotive cages, how they would never behave like that if they were walking. That might be called the "onroad disinhibition effect," for "cars" easily replaces "cyberspace" in that analysis. So too would "crowds." Seems like a lot of people will choose to be nasty if they can get away with it, without being "seen."

Such thoughts bloomed large in my mind when I returned to Los Angeles after spending August in Quebec-traveling from a place that is gentle to one that is harsh. September is often the hottest month of the year in Southern California, a season that glares, blares, and stares down at you with a relentless solar flare. (That bunch of rhymes started out accidentally, I swear-oops, there I go again! Can't help it, I guess, any more than I can help tapping on this tabletop while I'm thinking.)

From lake and woods and top-down gravel roads through cool green leaves and conifers, I was suddenly thrust into a jungle of concrete, glass, and steel, in a creeping mass of baking metal boxes. In my own cocoon, my eyes and heart were assaulted by a homeless guy sprawled on the sidewalk. Sirens wailed past to where an old Mercedes sedan had just punched its stately grille into a palm tree, dust and steam still rising. The driver stood beside it, apparently unharmed. (Those cars were built strong.)

A few blocks on a circle of emergency vehicles with flashing lights stood at the curb. Inching by, I saw a young guy being wheeled away on a gurney. He was sitting up to direct a paramedic who was trying to disassemble his bicycle to bring it along. Obviously he had been knocked down on his bike-but at least he was conscious.

Still-harsh.

As Olivia said to me on the phone a few days after she came back, "I miss Science Island."

Me too-can't wait to ski by it this winter, and row by it next summer, in my spiffy new racing shell...

|

Poised For Action |

As if that were not enough news, weather, and sports for one broadcast, I really must give a report on the avian visitors to Bubba's Seeds 'n' Suet. (No, no-I must, I really must!)

In order of "frequent flier miles," goldfinches were most numerous, along with chickadees, the two cheeriest species of birds in our woods. A pair of young red-breasted nuthatches appeared to be fresh out of the nest (years ago I looked out my bedroom window one summer morning and saw four thumb-sized nuthatches perched side by side on a branch, on their first outing). These two comical, nattily-feathered nuthatches fluttered clumsily to the feeder, all adolescent awkwardness, bumping and chasing each other around, stumbling on the perches. They made me smile, and I called them the "Knucklehead Nuthatches." Occasional mobs of blue jays swarmed in and chased the other birds away (though not the nuthatches and woodpeckers) while they rifled through the seeds. I also spotted a few house finches, white-crowned sparrows, a white-breasted nuthatch, and a downy woodpecker.

I noticed that none of them seem to care for suet in summer, while that mix of animal fat and seeds is popular with many species in winter-maybe it goes rancid? Perhaps it's a seasonal variation in diet-I have reported how the summer goldfinches favor tiny black seeds called niger (package now reads Nyjer), while in winter they don't touch those, but choose sunflower seeds.

|

Two Goldies and Two Knuckleheads |

In the grass below the feeder a number of squirrels and chipmunks nosed (probably thanking the sloppy jays), and we had regular sightings of deer around the house. One morning Olivia and I were on our way down to the dock when I caught a glimpse of brown velvet in the woods across the stream. I reached out a hand to Olivia's shoulder, then put a finger to my lips. A yearling deer stood twenty-five feet away, and we all stayed frozen for a couple of minutes-checking each other out.

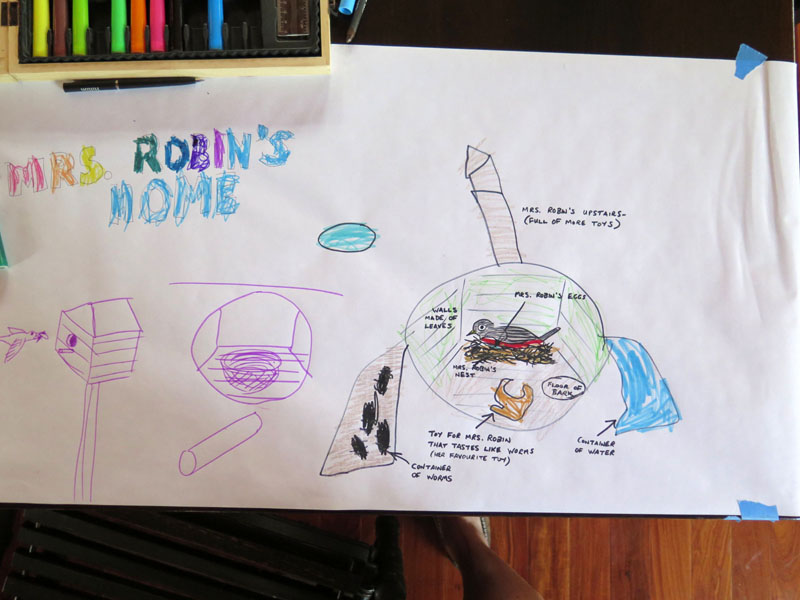

One day Olivia noticed an old birdhouse in the garage, and asked what it was. The concept puzzled her, and when we got to our "art table," I drew a quick sketch of a bird carrying a bug as it flew to a birdhouse. She wondered what it was like inside, so I sketched the view through the hole, with the nest made of grass and leaves.

|

art direction, vision, and colors by Olivia, preliminary sketches and lettering by Dad |

Well, Olivia had some ideas on building a better birdhouse. She drew a larger circle, then asked me to draw the inside. The walls should be made of leaves, the floor of bark, and there should be a bird on its nest. I decided to draw a robin sitting on its eggs. One of our crayons was called robin's egg blue, so Olivia knew what color to make them. I had told her before that robins ate worms, and she took the marker and drew an amorphous shape, colored it brown, and told me it was "Mrs. Robin's favorite toy-it tastes like worms!"

Thinking of every need for Mrs. Robin, she added a container of worms on one side, a container of water on the other, and an "upstairs room" that she said was "full of more toys." Lucky Mrs. Robin!

Olivia wanted to title the finished work "Mrs. Robin's Home," so I outlined the letters and she filled in the colors (we just say "ROY G BIV" for short now), plus robin's egg blue for the rest. "For the sky," she explained.

|

Bonus Picture |

Now Mrs. Robin joins the rest of our friends from the summer of 2014-Olivia the Pig and Princess Stephanie, Toot and Puddle, Boo and Buddy, Baby Loon and ROY G BIV, "Love Shack" and "Gangnam Style," Holly Shiftwell and Finn McMissile (a.k.a. Olivia and Dad), current favorite painters David Hockney and Jackson Pollock (she's David; I'm Jackson-when I requested permission to use one of Mr. Hockney's works in Far and Near, I shared with his representative that after Olivia viewed some of his works in San Francisco, she stood in front of her easel and declared, "David Hockney... inspires me"-the lady said she couldn't think of a nicer tribute), Merida and Angus (he's Merida's horse), all to be remembered and treasured for the rest of our days, in the timeless and unforgettable universe of Science Island.