A Life in Canadian Rock

Neil Peart's Foreword to The History of Canadian Rock 'N' Roll by Bob Mersereau

March 1, 2015

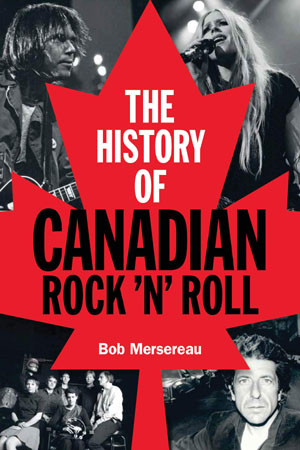

The History of Canadian Rock 'N' Roll

by Bob Mersereau

Foreword written by Neil Peart

Published March 1, 2015 by Backbeat, 320 pages, ISBN 1480367117

It must have been the summer of 1964, so I was going on twelve. A group of four or five families from our neighborhood was living in a ragtag cluster of tents at Morgan's Point, on the Ontario shore of Lake Erie. We were all camping there together for a few weeks that summer, while our dads commuted to St. Catharines for work. It was a boyhood ambience of sunburns, mosquito bites, campfires, a warm, shallow lake with a threatened undertow, playing coureurs de bois in the woods, and a first kiss under the sumacs.

One evening some of us kids were gathered outside the dance pavilion. We were too young to go in, and couldn't have paid anyway (to have a quarter of your own was a big deal then), but stood nearby to listen. Who can now imagine such a remote time, pre-everything, when a man could remember the first time he ever heard rock music?

(And if that makes me "old," I'm comfortable with it-proud of it. If a youngster tells me he was born in any later decade, my only response is sympathy: "You missed so much.")

According to the posters, they were called The Morticians. They were pictured in long-tailed suits and top hats, and the battered hearse they and their gear traveled in was parked outside. My first impression of live rock music was that it was loud-surprise. They probably had a bunch of fifty-watt amps, but I'd only ever heard Dad's hi-fi, the car radio's single speaker, and the little transistor pressed up to my ear at night. The guitars were brash, jangly and warmly, voices echoey and unintelligible, something low was rumbling the walls, and I couldn't understand why the drums sounded so metallic-not knowing what cymbals were. But the drumming sure galvanized my attention.

So did the noise...

It was the time of the British Invasion, and soon there were rock bands everywhere-in every dance hall, and in every second garage. In those years I often spent school holidays with my Blackwell grandparents in Georgetown, Ontario. By an accident of familial timing, my uncle Richard was just a year older than me, so more like a cousin. He played drums in a band called The Outcasts, emulating the "blue-eyed soul" trend that was everything in nearby Toronto.

Even as I took up playing drums myself (well, practice pad and magazines on the bed for the first year), the musical education that was being delivered to me in little old St. Catharines was, in retrospect, astounding.

It is probably safe to say, from this twenty-first-century vantage point, that there was no better decade in which to be a kid than the '50s, and no better decade to be a teenager-especially an inspiring musician-than the '60s. Discuss...

(If you missed it, see above sympathy.)

It was not radio or television or even word of mouth that introduced me to the music I came to love-it was cover bands. While I very much appreciated the R&B that influenced the "Toronto sound," and played it in some of my earliest bands (still identifiable in my playing today), the first music that really electrified me was the "second wave" of the British Invasion. That was when rock 'n' roll became rock, I guess-edgy, aggressive-sounding bands like The Who, The Kinks, and The Hollies. I did not hear that kind of music on Top-40 radio, not then, but I heard it played by Graeme and the Wafers. They were a mod-style band from the Prairies who took up residence in the Niagara Peninsula one summer-and rocked my world.

The bands I saw at high schools, the roller rink, and the Castle ("A Knight Club for Teenagers") included local heroes like The Modbeats, The Evil, The Ragged Edges, The Veltones (still remember their mournful single on CHOW radio from their hometown of Welland, "Just Another Face in the Crowd"), and dozens more, plus so many truly excellent bands from Toronto.

A few records trickled out from there, too, and we all liked the singles and albums by Mandala and The Ugly Ducklings. (One of my earliest conversations with bandmate Alex was about that album Somewhere Outside-including "Gaslight," a single that ought to have been a huge hit everywhere-and Alex laughed when I played the staggered drum figure that opened "Just in Case You Wonder.")

And the drummers! Anyone trying to lay down funky beats for those blue-eyed-soul bands simply had to have more chops that a surf-rock drummer. So they were all at least good, and some were masters whose playing still echoes in this eternal youngster's inner transistor. Whitey Glan with Mandala, Skip Prokop with Lighthouse, Graham Lear with George Olliver's Natural Gas, Danny Taylor with Nucleus, Dave Cairns with Leigh Ashford, and many more-all playing in my hometown on a weekly basis. Every drummer did a solo-it was simply expected-so even just standing in the audience, no young drummer ever had it so good.

Further afield, it was an adolescent thrill to see The Guess Who at a county fair in Caledonia, then again at the psychedelic youth pavilion called "Time Being" (1967, of course, the Summer of Love-still not fifteen, I was a little young for all that, but sure wanted to be part of it!) at the Canadian National Exhibition in Toronto. The next time I saw The Guess Who was at a pop festival at Brock University in 1969, with Mashmakhan (Jerry Mercer another great drummer) and a number of local bands-including my first band with a handful of original songs, J.R. Flood. In front of ten thousand people, I played a drum solo in Santana's "Soul Sacrifice," just as Michael Shrieve had done at Woodstock, and it received a life-affirming reaction.

My head didn't swell, but my ambition did....

In later years I would be privileged to become part of the history of Canadian rock, achieving unimagined success and accolades with my bandmates ("the Guys at Work") Alex and Geddy.

Even that road was illuminated by touring with other Canadian bands-crossing paths early on with The Stampeders, April Wine, the great Downchild Blues Band, as we all struggled as opening acts and playing rock clubs around the U.S.

This book spotlights the pivotal role played by Ronnie Hawkins in early Canadian rock, and he had his part in Rush's history, too. Our Moving Pictures album was written in the summer of 1980 at his farm near Peterborough-the same farm that hosted John and Yoko a decade earlier.

When Rush started to headline, we were able to bring other Canadian bands, like Max Webster and FM, on our U.S. tours. We even brought Max on a European tour-but even then they never caught on in the way we, as fans, expected they would. That "divide" remains a mystery-why so many great bands, from the '60s and up through the '70s and '80s, failed to make that connection with American (or European) audiences. (That is to say, even when they had the opportunity.)

The Tragically Hip are another puzzling example. As a longtime fan of theirs, singing their praises, I sometimes describe them to unaware Americans as "the Canadian Pearl Jam." In some aspects, notably lyrics and arguably songwriting in general, The Hip are the superior in that comparison-but again, by and large, Americans didn't "get" them. I don't get that.

Seeing them play at the House of Blues in West Hollywood one time in the early 2000s, I had rarely seen an audience more engaged with a band's songs. But alas, there weren't as many in that audience as there might have been....

The rest of the story can be left to the book you are about to commence reading. It is enough to say that the history Bob has researched so lovingly, and woven so deftly into an entertaining story, reflects a vitality, a creativity, and a power that is profoundly worth celebrating. It begins at a time when the only native rock was... the Canadian Shield and the Rocky Mountains....

Neil Peart, 2015