"Natural Science" - "New World Man" - "Mystic Rhythms"

"...Madmen fed on fear and lies..."

By James McNair, Dave Everley, Geddy Lee, Planet Rock, Issue #13/April 2019, transcribed by John Patuto

Back in the 1970s, Rush were the biggest cult band in the world. Then the Canadian trio tore up the rule book and reinvented themselves for a new decade. In a rare - and exclusive - new interview, Alex Lifeson revisits the extraordinary madness of prog rock's most singular and subversive band.

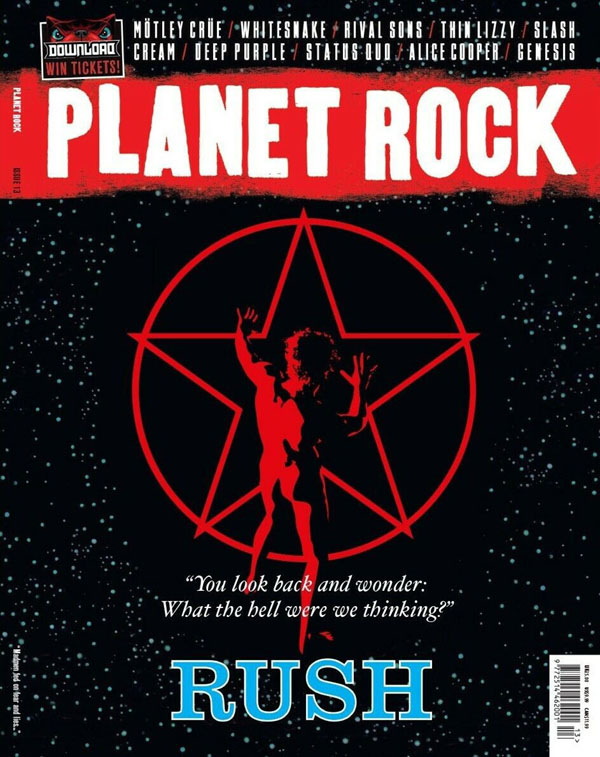

Rush divide opinion, like all the most iconic artists. There are those who consider the Canadian trio one of the most daring, imaginative, unique and influential rock bands in history. There are also alternative (wrong) opinions, but those need not detain us here. Personally, having opened a portal to Rush's fantastical world via a borrowed copy of 1981's Exit...Stage Left album, it's an honour to welcome the Toronto band to the cover of PR 13, and a pleasure to read Alex Lifeson's witty, warm-hearted reflections on the group's incredible four-decade career in our exclusive cover interview.

Natural Science

For much of the 1970s, Canadian power trio RUSH made challenging prog rock records that confounded non-believers with their howling vocals, science-fiction stories and references to Greek gods and Tolkien. Then 1980's radio-friendly Permanent Waves and its mega-selling follow-up Moving Pictures propelled them into the rock stratosphere. James McNair unfolds a tale of cross-dressing, heavy drinking, NASA space launches and three men on a quiet mission to conquer the planet.

It's March 13, 1980...and having checked the tv listings, UK Rush fans are excited. The Toronto-formed power trio's new single, The Spirit Of Radio, has charted, and it seems they are to be guests on Top Of The Pops. Rush won't be touring new album Permanent Waves in the UK until June, and in this pre-MTV, pre-internet age, a gig is pretty much the only way to see them. TOTP is big news, then, and Rush's rabid fan base duly tunes in.

"Here's something else Canada has given us apart from Gordon Lightfoot and The Mounties," quips TOTP host Steve Wright, and for a fleeting moment there is a God. But wait... fecking Xanadu! Rush are conspicuously absent and The Spirit Of Radio is being performed by Legs & Co. through the medium of interpretative dance. In a rare instance of spotty young men rebuffing nubile young women, some of the male contingent of Rush's fan base switch off in disgust. Legs & Co. are at it again on TOTP the following week as The Spirit Of Radio climbs to Number 13. All lip gloss and big hair, one of the girls yawns cutely as Geddy Lee sings, "Begin the day with a friendly voice..."

They weren't wearing lip gloss, but Rush had also started to attune themselves to '80s trends. When they played Glasgow Apollo on June so and is, some fans were aghast that guitar god Alex Lifeson had undergone a makeover, swapping silk scarves, a hirsute expanse of bared chest and his waist-length crimped hair for a skinny tie, a shorter barnet and a jacket that might have come from Topman.

Such stylistic updates signalled a band undergoing a total re-think - not least regarding their music. Released at the dawn of a new decade on January 14, 1980, Permanent Waves was the Rush album which saw subtle New Wave influences begin to infiltrate the band's prog and classic rock roots.

"I had been working on making a song out of a medieval epic called Sir Gawain And The Green Knight," Neil Peart wrote in the Permanent Waves tour programme. But tellingly, the Gawain angle had been put to the sword, its grandiose subject matter ultimately deemed out of step with the new, '8os-savvy Rush.

"There had been a shift from the last vestiges of the rock scene of the early '70s to the punk movement," Lifeson later told writer Paul Elliott. "And by 1979, when we started working on Permanent Waves, we were not so much in our own little world." Now, songs inspired by Tolkien, Greek mythology - or, indeed, The Knights Of The Round Table - were out, while lyrics about human relationships, ethics, and the simple joy of listening to the radio were in.

All the same, Rush were still Rush, and while the group was starting to big up certain New Wave acts, the title of Permanent Waves was in part an act of defiance, upholding the enduring worth of old-school musicianship. The LP had time-signature changes galore, Peart was still an inspiration to air-drummers everywhere, and Lifeson's emotive solos on Freewill and Different Strings were among his best to date.

"I think there are two ways you can write songs," Rush's frontman and bassist extraordinaire Geddy Lee explained to Canadian magazine Music Express in January 1981. "Either you approach the lowest common denominator or you assume everybody out there is the ideal listener. We prefer the latter approach. We try to appeal to [our fans'] intelligence."

Rush had closed out the '70s with A Farewell To Kings and Hemispheres, two albums recorded at Rockfield Studios in rural Wales. Tiring of the Monmouthshire drizzle and the expense of recording abroad, the band returned to Canada to make Permanent Waves in Morin Heights, Quebec. At Le Studio, wall-sized picture-windows brought natural light and views of the Laurentian Mountains. A private lake and Lifeson's lasagne recipe also fed into the easy atmosphere.

"Making that album was incredibly relaxing," the guitarist told your scribe in 2003. "We'd play volleyball, and row across the lake to work. It was autumn, but a kind of Indian summer and [producer] Terry Brown's little cocker spaniel Daisy was running around." It was on The Spirit Of Radio, a song inspired by the slogan of Toronto station CFNY-FM, that the good vibes spilled over into the music. Lifeson's joyous, looping guitar figure was his approximation of a radio dial surfing the airwaves, while Erwig Chuapchuaduah's subtle steel drums on the song later provided Rush trivia quiz compilers with a tough question.

Peart, ever the antidote to all drummer jokes, was beginning to hone a different, more personal kind of lyric circa Permanent Waves, hence Entre Nous, a brilliant exploration of the limits of human empathy. Neil being Neil, though, he still made room for something a little more esoteric. Clocking in at nine minutes and 20 seconds, and split into three sections titled Tide Pools, Hyperspace, and Permanent Waves, Natural Science wasn't very Ultravox or The Police.

At root, the song called for a more balanced and thoughtful approach to the oft-competing disciplines of science and nature. "What it boils down to really," Peart told Innerview magazine in March 1980, "is we've just got to take ourselves in hand. It's [human beings] that need taming, not nature."

Further into the same article, Peart spelled out what was important to Rush as musicians.

"A pet bee in my bonnet, I think, is integrity" he noted. "I think the most important thing for any musician to learn is how to say no: 'No, I won't do that; that's not why I'm here; that's not why I spent six years learning my instrument.' I don't see the glory in being a full-time musician if you're not playing the music you love to play."

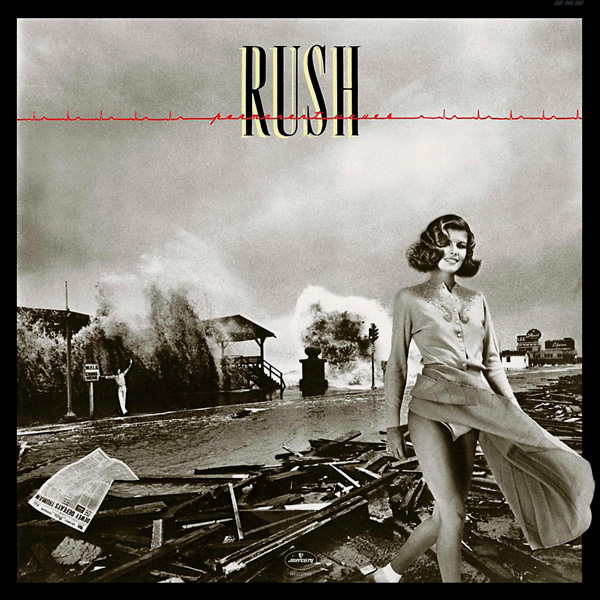

The sleeve of 1979's Hemispheres had depicted a naked male ballet dancer prancing atop a brain. Consequently, it had been an awkward talking-point for Rush fans quizzed about it by less enlightened school-mates, for whom a naked man's bum on an album sleeve still seemed uproariously funny. The cover of Permanent Waves, in contrast, featured leggy Canadian model Paula Turnbull flashing her knickers. While some fans had ported Hemispheres around town under wraps in an Our Price carrier bag, with Permanent Waves they let it all hang out.

Controversy adhered to the Permanent Waves sleeve in any case. Some 32 years after the Chicago Tribune's infamous "Dewey Defeats Truman" headline had miscalled the result of 1948's US Presidential Election, the paper objected to Rush and their art director Hugh Syme reprinting it on the album's front cover. Later print runs of the artwork would have the headline blanked out, and when soft-drink giant Coca-Cola objected to Waves' use of their logo, subsequent editions replaced it with Lee, Lifeson and Peart's surnames.

Rush's UK tour in support of Permanent Waves ran from June 1 to June 22, 1980, following two isolated UK dates at Bingley Hall, Stafford in September 1979, where punters heard work-in-progress versions of The Spirit Of Radio and Freewill. Already road veterans with a good 12 years on the clock, all three men were married fathers by 1979, and this, together with their upbringings -"we're good middle-class boys from the suburbs", noted Lee - meant they tended to approach the typical temptations of touring more circumspectly than their more rock'n'roll peers.

"Perhaps the secret of a successful marriage is absence," Rush's singer later joked when I asked him about faithfulness and groupie culture. "If you discount time spent asleep and time on the road, none of us has actually been married for that long. But seriously, we'd rather stick it out and fight it out - that's just the way we are with our marriages. Plus, by the time lots of girls started coming to our shows we were way too old to take advantage of it!"

Lee's tongue was firmly in cheek, of course, but Rush were never squeaky clean - and especially not in the '70s and early '80s. A Passage To Bangkok from 1976's 2112 testified to their love of cannabis, and as events after those aforementioned Bingley Hall shows demonstrated, they liked a drink too. Rush's support in Stafford came from Wild Horses, a band featuring two legendary Scots hell-raisers: ex-Rainbow bassist Jimmy Bain, and ex-Thin Lizzy guitarist Brian Robertson. When the two bands communed, a cup of Horlicks then bed wasn't an option.

"I remember us all being drunk with Jimmy in this bar called Mortons," Geddy Lee told me in 2003. "He was going, (passable Scottish accent) 'Geddy, you're brilliant! Take ma shoes! You've got to have ma shoes!' I said, Jimmy, I've got footwear - you'll have nothing to wear home. He wasn't having it, though."

"Yeah, I think I remember that night", Brian Robertson told me in 2010. "I definitely remember Alex travelling around with a flight-case full of Chivas Regal. They could be pretty crazy, those guys. One night, Alex turned up at my hotel dressed in a smoking jacket and a cravat, and Geddy had on a frilly woman's nightie and high heels. They started doing this bizarre skit based on some North American comedy series they'd seen as kids, acting it out in funny voices. It was totally lost on me."

Roberston also recalled the power of Rush live, having also toured with them while in Thin Lizzy. "You couldn't believe that it was just three fucking guys making that big a sound. By the time we supported them in Wild Horses they already had the bass pedals and some synths, but even still..."

Prior to starting work on their next album, Moving Pictures, Rush enjoyed a musical palette cleanser with Canuck pals, Max Webster. The two bands were close from years of touring together, and Max Webster keyboardist Terry Watkinson had given Geddy Lee some of his first synth lessons. On July 28, 1980, during a huge thunderstorm, the two bands joined forces to record a live-in-the-studio version of Battle Scar for Max Webster's criminally unsung album, Universal Juveniles. Peart recalled the joyous "Wagnerian tumult" that ensued at Phase One Studios in Toronto, and the day's good fortune didn't stop there. Pye Dubois, the Canadian poet who wrote Max Webster's lyrics, was present at the session, and wondered if Rush might be interested in some new words of his. Long-term fans of Dubois' work, Rush were interested, and his lyric, then titled Louis The Lawyer, was ultimately reworked for Tom Sawyer, Moving Pictures' much-celebrated opener.

Rush had actually been musing upon an in-concert sequel to 1976's double live set All The World's A Stage. But feeling inspired and motivated, they launched into another studio album instead. They were back at Le Studio in Morin Heights for the whole of October and November 1980, but this time sessions were more taxing. Problems with guitar sounds and deciding upon the perfect arrangements for some testing new material made Moving Pictures a difficult nut to crack.

Light relief again came in the form of volleyball, the band often playing out in the floodlit yard of Le Studio into the wee small hours. "It was minus 20 degrees," recalled Lifeson, "but we drank plenty of cognac to keep us warm. People were falling over, but it was a riot and it kept our spirits up."

Back indoors, one of the few tracks that came easily was YYZ, a dazzling instrumental named after the identification code for Toronto's Pearson International Airport. A skewed celebration of coming home off tour, the tune's odd-meter opening spelled out 'YYZ' in Morse code. "It's always a happy day when YYZ appears on our luggage tags," noted Peart.

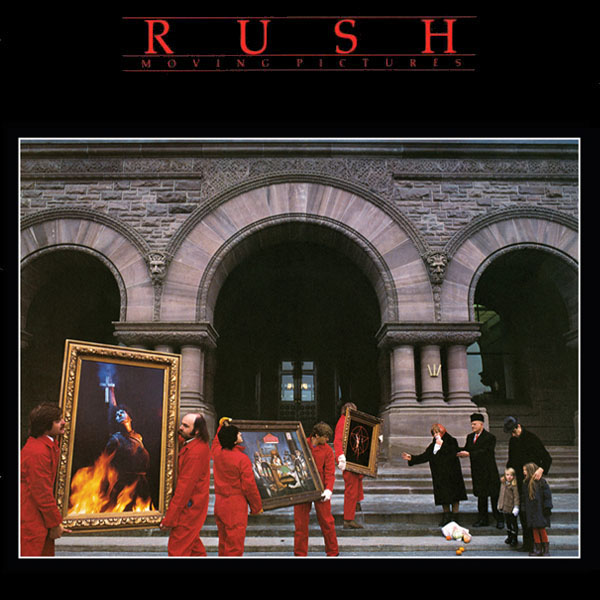

As was customary, the album's sleeve had a visual pun (Look! Men moving pictures!), but elsewhere much was new. Fizzy Oberheim OB-X synthesizers were more to the fore on Tom Sawyer, while on Vital Signs, a taut, reggae-imbued closer that had arrived at the 11th hour, the influence of The Police's Stewart Copeland could clearly be heard in Peart's drumming. Lee's voice was changing too. Long subject to slurs of the 'chipmunk on acid' variety, it now began to lose a little altitude - but without sacrificing any of its passion and power.

"Yeah, some of those old insults I got about my voice were a little painful," Lee told me in 2003. "I'm a human being, after all. On our early records I was like, If the music needs me to howl like the damned in Hades, then I will howl! But from Moving Pictures onwards it wasn't really appropriate any more - that wasn't what the material called for."

Elsewhere on the record, Lifeson's wonderfully atmospheric solo on Limelight seemed to stop time itself, and would become one of his favourites to play live, while Red Barchetta - part-inspired by Richard Foster's 1973 short story A Nice Morning Drive, and named after a style of Italian sports car - told a futuristic story about a world where such vehicles were banned (shades of 2112's censorious priests, anyone?).

It was Limelight, though, one of Peart's most personal lyrics, which spelled out exactly why you wouldn't find the introverted drummer present at any of the fan meet-and-greets that Lee and Lifeson would later wholeheartedly embrace. "I can't pretend a stranger is a long-awaited friend", ran part of Peart's lyric, an eloquent debunking of fame and some of its less desirable trappings. No wonder Rush fans who had managed to acquire the drummer's autograph counted themselves lucky.

Moving Pictures' stand-out track, the aforementioned Tom Sawyer, was simply an instant classic, a song which Geddy Lee later described as Rush's "defining piece of music from the 1980s" It would spill over into wider popular culture, as demonstrated by the version sung by South Park cartoon character Eric Cartman in tribute band 'Lil Rush. "A modern day warrior named Tom Sawyer/He floated down a river/On a raft with a black guy," screeched Cartman. He was paraphrasing, obviously, but Rush loved the irreverent nod, and used the clip that South Park creators Matt Stone and Trey Parker had made specially for them in their live show's rear-screen projections from 2007 onwards.

"Matt and Trey were fans and we'd become friends," recalled Lifeson. "When we asked them to do it they were all over it. In fact, they came back from their holidays specially to do it in time for our deadline, and we just thought it was hilarious."

This was just one example of Rush's self-mocking sense of humour, something often overlooked by the band's detractors. "Yeah, it's always been the 'serious' songs about Greek Gods and mythical creatures that have gotten the most flash in the press," Lee told me. "That and Neil reading [controversial Russian-American novelist and philosopher] Ayn Rand. Critics said we were humourless, but in the early days at least 'stupid' would have been more accurate. Journalists would say we were pretentious and me and Alex were like, "What is it they think were pretending to be?" That's how stupid we were.

The second half of Moving Pictures kicked off with The Camera Eye, Neil Peart's lyric an affectionate nod to the streets of New York and London. A curious and unwieldy beast with some ace moments - plus, at one point, a Dick-Van-Dyke-does-Cockney voice saying, "Alright guv?" - the song was the last-ever Rush composition to breach 10 minutes, and wouldn't age particularly well.

"Yeah, that one needed a huge edit," Lifeson told me years later. "The Camera Eye was like this strange hang-over from our pomp-rock days, something overly influenced by bands like Genesis, and not actually entirely Rush-like."

"Sometimes you look back at stuff and think, Jesus! What the hell were we thinking?" chipped in Lee. "But even The Camera Eye was an honest expression of where our heads were at, fucked up as they might have been."

Released on February 12, 1981, Moving Pictures proved to be a true landmark for Rush. Often cited as one of the finest works of their career - and the record which even the most casual Rush fan tends to know - it reached Number 3 on both sides of the Atlantic, and would eventually sell more than four million copies in the US alone. The days when you could catch the band at London's Hammersmith Odeon were now officially over. Rush had joined the school of rock's elite, taking their place among a select group of world-beating stadium acts.

"Everything changed," recalled Lifeson. "Before that, we were still in debt, but when Moving Pictures came out we were able to renegotiate our deal and a lot of our financial worries disappeared. The intention was to take our foot off the gas a bit, but we still toured a lot. The obvious thing to do was to put out another live album..."

Rush's second double-live set Exit... Stage Left arrived on October 29, 1981, but the band enjoyed some down-time in the months before its release. One particularly special day out came on April 12, 1981, when Lee, Lifeson and Peart were among a select few privileged to watch NASA launch their Columbia space shuttle at Cape Canaveral, Florida. "It was deafening," recalled Lifeson. "Louder than Van Halen. The ground shook and we decided we were going to write a song about it right away [this turned out to be Countdown, from 1982's Signals].

Clocking in at one hour and 16 minutes, and recorded in Montreal and Glasgow in 1980, Exit... Stage Left featured 12 classics from Rush's career to date, plus one little curio. Broon's Bane, named for Rush's producer Terry Brown, was a haunting Lifeson acoustic guitar piece. Vibrant versions of Tom Sawyer and The Spirit Of Radio helped propel the album to Number 10 in the US, and the "Glaswegian chorus" got a sleeve credit for singing bvs on a version of Closer To The Heart recorded at the Apollo. But in truth Exit... wasn't a recording that placed the listener at the centre of the action. "There was a lot of meddling with the tapes to try and make sure we had the best performances," Lee later conceded. At times it felt like you could hear the joins, and in the press, Rush held their hands up to the album's fixes.

The band were out on the road again in support of Exit... Stage Left from October 1981 until three days before Christmas. So much for taking their foot of the gas. For Peart it was another chance to feed his voracious appetite for books, gathering inspiration for new lyrics. "The down-time of touring was always tedious to me," he noted years later. "Reading became my escape and a nurturing way to actually spend time, rather than killing it."

As 1982 got underway, Rush looked like a shoo-in for Best Rock Instrumental Performance at the Grammy Awards that February. But Moving Pictures' YYZ lost out to The Police's Behind My Camel, a tune from 1980's Zenyatta Mondatta which Sting didn't play on, and about which its co-producer Nigel Gray said: "What would you find behind a camel? A monumental pile of shit."

Police fans to a man, Rush were gracious in defeat, but having begun the new decade with two much-acclaimed studio albums, they could afford to be. "In the early-to-mid-1980s we were at our peak popularity first time around," said Lifeson, yet that level of fame and success was as nothing compared to what lay up ahead. Scot McFadyen and Sam Dunn's acclaimed 2010 documentary Beyond The Lighted Stage - and Lifeson's audaciously daft 2013 speech as Rush were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame - cemented the love folks felt for the Canuck trio, but they finally called time in 2018, citing the great pain Neil Peart now felt while drumming.

It was back in 2015, though, that Peart gave a quote which again underlined the importance to Rush of 'integrity' "People say, 'Did you ever dream you'd play Madison Square Garden?'" he told Sirius XM. "No. I dreamed of playing at the roller rink and my high school - your goals increase over time."

New World Man

Widely acknowledged as one of rock's finest guitarists, ALEX LIFESON was always Rush's unsung hero. When the band split in 2015 at the end of their 40th anniversary tour, Lifeson quietly slipped out of the limelight, but Planet Rock has coaxed him out of retirement for a rare and exclusive look back over the Canadians' extraordinary career. "We did it our way," he says, proudly.

"It Hurt Like Hell."

This is Alex Lifeson's memory of being repeatedly tasered on New Year's Eve 2003. Rush's guitarist was arrested while trying to defend his son Jason in the face of heavy-handed security at The Ritz Carlton Hotel in Naples, Florida. John Cannivet, a former Ritz Carlton employee and eyewitness, later stated that Lifeson and his family had suffered "extreme police brutality" Lifeson's own recollection is that "it was like a shock from an electric fence times a hundred"

For Rush fans, the incident seemed out of character for the guitarist. Sure, Lifeson liked a drink and took the piss out of Kiss in the animated series Big Al's Tiki Bar, but street brawls? Hardly the MO of this famously fun-lovin' and gently humorous rock icon.

Born Alexandar Zivojinovich on August 27, 1953, Lifeson would have learned accordion if his Yugoslav parents had their way, but thankfully for rock fans he learned guitar instead. Over 19 studio albums with Rush, beginning with 1974's self-titled debut, he developed an adaptable, yet instantly recognisable, style alongside fellow virtuosos Geddy Lee and Neil Peart, his soloing full of deliciously eccentric phrasing on classics such as The Spirit Of Radio and Tom Sawyer.

Lifeson was always the most flamboyant and mischievous member of Rush, "the class joker", by his own admission. He rocked white silk strides and a fedora on the sleeve of 2112, glued hotel-room furniture upside down with Thin Lizzy's Brian Robertson, and occasionally caused playful umbrage while dressed as 'The Bag', of which more later.

But all good things must come to an end, and after wrapping their R40 Live 40th Anniversary Tour at the Los Angeles Forum on August 1, 2015, Rush disbanded, citing the increasing physical pain Neil Peart felt while drumming as the very necessary reason for their demise.

"It wasn't until about a year later that I started to feel better about it all," says Lifeson today. "I realised we'd gone out on a high note."

What's your fondest memory of that final tour?

The closing show in Los Angeles was very powerful. I remember looking around the whole arena and trying to take it all in. The lighting. The crowd. The people around me. It was very emotional for us. I loved the way we presented those shows, starting with [final Rush album] Clockwork Angels and then working our way back to the very beginning. But had we done a typical-length tour of about 80 dates, I think I would have been more satisfied with it.

But you've since come to terms with Rush being over?

Yes, I think so. I don't want to be in a band and tour any more. I don't feel the need to carry on with what I did for almost half a century. I'm fine with it now. And I'm as busy as I would ever want to be.

Busy with invitations to play on other people's records...

Yeah, I do get quite a few. And I take up almost every offer. It's fun! It's mostly manipulating the guitar for new sounds. I can smoke a joint and do that for weeks (laughs).

When Geddy Lee played with Yes at their Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction in 2017 it obviously meant a lot to him. Watching that, did you have a fantasy equivalent, some thought about who you'd like to sit in with?

Well, Chris Squire was a huge influence on Geddy's bass playing. So to have that request - and to play on Roundabout of all songs - was something Geddy wasn't going to pass up. I suppose the equivalent for me would have been to get up and play with Zeppelin when they were inducted. I've been such a fan of Jimmy Page over the years.

Let's go back a bit. Your eldest son Justin was born in 1970, four years before Rush put out their debut album. How did that early responsibility affect your career?

I was only 17 years old, so it was a rocky start for me and my wife Charlene. I was just finishing high school and music was everything to me. It was a difficult thing to take on.

But you and Charlene are still together...

Well, it worked out for us. Relationships don't often work out under those conditions. There was a connection between me and Charlene that was very, very unique to us. We managed to get through that and many other rough points in our history together. When I was growing up divorce was rare, you worked things out.

Last January, for International Holocaust Remembrance Day, Geddy gave his most detailed interview to date regarding his family's horrendous experiences at three different concentration camps. As kids hanging out together in Rush, was there a point he confided his background to you?

Oh, I knew about it from the beginning. The first time I met Geddy's mum I saw her concentration camp number tattooed on her arm. That stayed with me. My parents came from Yugoslavia, and my father was in a work camp in Austria. The war affected everybody. Both my parents came to Canada as undocumented refugees. So Geddy and I shared a common background, and that really bonded us. Two Canadian-born Eastern Europeans whose parents had been displaced by the war.

In Rush, when did you first alight on a guitar style where you thought: this is me, this isn't just the sum of my influences?

Probably around the time of 2112. My main guys were Townshend and Page and Beck, but Steve Hackett was in there, and so was Steve Howe. I don't know how aware of my influences I was, but I took a little bit from everywhere. I think that's how it is for most musicians. You have to start somewhere. I was lucky. I was born at a time when all the electric guitar greats were coming through. But I think it was on 2112 that I really started to think about my sound and my style, rather than, "What would Jimmy do here? What would Pete do there?" I always felt like I had to take up as much space as I could. We were only a three-piece.

I guess not many Rush fans would single out Tears from 2112 for special mention, yet when Alice In Chains covered it for the 40th Anniversary reissue I was reminded what a great song it is...

Yes, that is a good one. On those earlier albums we always had a track that was a kind of production number that we didn't intend to do live. Tears was like that. So was The Twilight Zone [also from 2112], although we did end up playing that live. As a singer, Geddy would gravitate towards those very melodic tracks. That was always his nature. That was how our relationship worked. I was very instinctive. All my best stuff was in the first couple of takes. Ged was more methodical. I would get impatient, but Ged's approach served us well.

We read that there isn't much unreleased Rush stuff in the vaults, but there must be something? From the Fly By Night or Caress Of Steel sessions, perhaps?

No. There really isn't anything. We only focused on what was going to be on the record. We were never the sort of band that recorded 20 songs and picked the best 12. All that's in the vaults is a load of crazy outtakes. Moments between recordings when we would have some fun. Will those ever be released? Some of them, perhaps. Others, absolutely not (laughs).

Let's explore the legend of The Bag, by which I of course mean the big paper laundry bag with a stupid face drawn on it that you would put over your head to make mischief while on tour in the early days.

Well, what can I say? The Bag was The Bag. I had no control over what The Bag did. I was always the class clown and I always had a twisted sense of humour, so The Bag appealed to me. It used to appear a lot when we were hanging out with Ace [Frehley, Kiss guitarist], because Ace adored The Bag and he was always shouting, (drops into Frehley's screeching Bronx accent) "Alex! Bring out The Bag!" So I'd draw this goofy face on a Holiday Inn laundry bag, poke out some eye holes and go with it. The Bag had no internal editor, so he would say whatever he wanted to whoever he wanted, usually causing some offence, or if it was Gene [Simmons, Kiss bassist] pure anger (laughs). The Bag made a few appearances at pool parties, too.

Thin Lizzy's Brian Robertson told me that you'd also travel around with a flight-case full of Chivas Regal, and that, one night, you turned up at his hotel dressed in a smoking jacket and a cravat, with Geddy in a frilly woman's nightie and high heels. Can you shed any more light on that evening?

"Evening?" I think you mean "evenings" (laughs). I got so close with Brian. He and I were like soul brothers. I loved that guy so much. We were very close with Thin Lizzy, and I remember we played a lot of three-way shows together when Styx was the headline act. Styx weren't very friendly or approachable, so we hung out with the Lizzies, drinking like crazy and waking up in each other's tour vans.

So it's all true?

Yes. We were really into Chivas Regal at the time, even although it was a blended whisky. We're much fussier now. I remember me and Brian glued a hotel room upside down. But the dressing up thing he told you about was me and Ged's tribute to [late '50s, early '60s US sitcom] Leave It To Beaver. I played Ward, and Geddy was my wife, June, and we'd show up in character at these drunken hotel-room parties. But my recollection is that Brian loved it. In fact, he got himself a housecoat and a hair net and he became another character called Judith.

Scot McFadyen and Sam Dunn's acclaimed 2010 documentary Rush: Beyond The Lighted Stage was very significant for the band. Do you think it changed people's perceptions of you?

It did. Very much so. Playing in Rush day-to-day I think we missed the significance of some of the things that happened along the way, and we didn't think there was a story there. When Scot and Sam proposed the idea we tried to discourage them, but they said, "No. You're wrong. We think there's amazing stuff here that you just aren't aware of." I remember seeing the first edit and being blown away by it. I thought, "This is a fascinating story with a lot of humour in it and for once it shows us as we actually are."

What did the film change?

Well, we all know the jokes, don't we? The ones about how it's best to go to the women's loo at Rush shows because there won't be anybody there (laughs). But after the film, I think that mothers, particularly, began to feel a strong connection to us. Suddenly we saw many more women at the shows. And not just women with their men - groups of four or five women on a girls' night out.

The stills of you all in your Y-fronts when John Rutsey [first Rush drummer] was in the band and the drunken meal you, Geddy and Neil have at the end: you obviously gave McFadyen and Dunn free rein...

Completely. This was their documentary, not ours. We knew we had to stand back if we wanted to get an objective view of our story. People said nice things about the drunken dinner footage. Scot and Sam set the cameras up and disappeared, so after a while we weren't even aware we were being filmed, and the more we drank the crazier it became. It gave a good snapshot of our friendship and our connection. That was exactly how it was for us for 46 years.

Your infamous "blah, blah, blah" speech when Rush were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2013 caused quite a stir. Is it true that Geddy and Neil had no idea what was afoot?

Well, until the last minute, I didn't know myself! We had a little rehearsal in the afternoon, just checking the teleprompter was working. I was reading my speech and trying to memorise it - no easy task when you get to this age. In the end I thought, "I should just get up and go blah, blah, blah or something." And then it was, "Oh my God! Do I actually have the balls to get up there and do that?" So, during the actual show, when we were sitting at the table, I leaned over to my wife to tell her my plan. Then somebody gave this very serious and grand speech and she was like, "And you're gonna [go] blah, blah, blah?"

But what transpired was pure satire, you taking the piss out of celebrity speeches...

Well I committed to it as I was walking up to the podium. And, yeah, I did have a mischievous smile on my face, because I was thinking to myself, "Al. You're gonna do this." Geddy and Neil had no idea what was going on. I think they were confused. I had my back to them and they couldn't see I was acting out the whole story of Rush and how we got there.

I'm not sure I understood all of your miming, either, but you obviously felt you were acting out something quite specific.

Exactly. Plus all these people were getting up and giving these long-winded speeches, most of which were really fucking boring. I thought, "Here we are in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame - isn't rock supposed to be irreverent?"

So what was Geddy and Neil's immediate reaction after you basically said "blah, blah, blah..." for three minutes?

They wanted to kill me. They were really upset. They were like, "What is the matter with you? How could you do that after our heartfelt speeches?" Then the following day I got an email from Neil saying, "I owe you an apology the size of Texas. I am so sorry that I got upset. I've been inundated with emails from everybody I know saying, 'Wasn't Alex's speech great?"

Will you ever get around to following up your 1996 solo album, Victor?

It's a different time in the industry. Victor was a very personal project for me and I wanted to be in charge of every single little thing. I feel like I could have done a better job, for sure, but it gave me what I needed at the time. But to make a follow-up album today? I don't know. That said, I probably have enough material for three or four solo albums. I listen back to the stuff I've been doing every now and then and I love the songs and then I hate them. It feels kind of meaningless because I'm not locked into anything anymore.

Where do you stand on the 'never meet your heroes' thing?

I'd say meet them, just don't be a crazed fan. When me and Geddy went to see Page & Plant in 1998, that was big. Geddy had been staying at the same hotel as Robert [Plant] in Morocco, and they'd smiled and nodded at each other a few times. Then on the last night Geddy said to his wife, "I've got to go over and tell him how much he's meant to me." So he did, and Robert said, (drops into passable impersonation) "Oh, Geddy! It's about time you came over - sit down and have a glass of wine." Anyway, next time they came through Toronto Robert invited me and Ged down to the show, and when Jimmy introduced himself I was like (scared voice), "Whoah.. it's Jimmy Page!? He was so gracious, though. A real gent. It was interesting, because a half-hour before Rush shows nobody got to come anywhere near our dressing rooms, yet we were joking with Jimmy and Robert until the last minute before they went on. We even walked down to the stage with them.

You've been a licensed pilot for many years. What thrill did flying bring that you couldn't get from music?

Well you could easily kill yourself flying, so there was that thrill. Being in a big fancy-schmancy rock band you hire people to do everything for you. So flying was about me taking control again.

Who would win at golf, you or Alice Cooper?

Alice for sure. He is much more of a golf addict and much steadier. Golf became an important part of his therapy as he moved out of his addictions - and that was many, many years ago now. Alice still plays every day. Maybe just nine holes on a show day, but still.

I read that, although the official line is that Neil has given up drumming, he's actually teaching his daughter how to play. True?

(Cautiously) I think he might be. I know that he supports her interest in playing drums. He's definitely provided some guidance for her, yeah.

So if you and Geddy just hang around for another 10 years you could be out there playing I Think I'm Going Bald with Neil's daughter?

Yeah (laughs). Great!

Seriously, though, what's your conversation like when you and Geddy see Neil these days? Do you talk about Rush?

We seldom talk about the band. But we might get nostalgic about certain memories, and we certainly share a laugh. Neil lives in Los Angeles, but the three of us try to get together a few times a year. We have a great time. We talk about current events and our families and we always share a couple of great dinners and plenty of wine.

Not many bands who were together as long as you were still have that.

It's fantastic. I can't think of another band from our era that are still friends like we are still friends. The Stones never see each other unless they're working. The Eagles hated each other for decades. ZZ Top couldn't stand each other. But it's high pressure being in a touring rock band and people change as individuals. The Grateful Dead was the best one. They had different-coloured tape designating the different guys' stage areas, and nobody was allowed to cross somebody else's line (laughs). And we thought the Dead were brothers, man!

So what kept Rush together all those years?

Coming home off tour and no longer being fancy-schmancy rock stars. Taking the kids to school. Picking up the dry-cleaning on the way home. We weren't single crazy guys who could just party on. We loved being together and we laughed so much. And we cared so much. What Neil went through [Peart lost his first daughter Selena, then aged 19, in a car crash in August 1997 then his first wife Jacqueline to cancer 10 months later] was just so devastating for him, obviously, but also for all of us. And yet we came back again and managed to regain the level of workmanship that we'd aspired to from the beginning. That's probably the one thing that I'm most proud of. We did it our way.

Mystic Rhythms

Precious artefacts uncovered in a deep dive through Rush's back catalogue.

1. BY-TOR AND THE SNOW DOG

1. BY-TOR AND THE SNOW DOG

(on Fly By Night, 1975)

"Tobes of Hades lit by flickering torchlight..." So begins Rush's first ever fantasy epic, a wonderfully preposterous account of a battle between By-Tor (Lee) and Snow Dog (Lifeson). The crazy time-signature changes; the Olympian drum-fills; the growling, treated voices; and chimes that bring things to a close after eight minutes, 37 seconds - what's not to like?

2. LAKESIDE PARK

2. LAKESIDE PARK

(on Caress Of Steel, 1975)

Neil Peart's sketch of childhood innocence at a park in the Port Dalhousie suburb of St Catharine's, Ontario was one that Lee and Lifeson could easily identify with; Peart spent time there as a fairground worker in the summer of 1966. A wistful, tautly arranged song with a magical Lifeson solo.

3. LESSONS

3. LESSONS

(on 2112, 1976)

Tucked away on 2112's less-celebrated Side Two, Lessons blends grooving acoustic verses with barnstorming, power-chord driven choruses, Lee repeatedly screaming, "You didn't listen again!", at the top of his magnificent range. A rather Zeppelinesque affair, and a rare example of a Rush song written solely by Alex Lifeson, lyrics and all.

4. RED SECTOR A

4. RED SECTOR A

(on Grace Under Pressure, 1984)

One of the most emotive songs in Rush's entire back catalogue, and for an obvious reason: Peart's lyric was partly inspired by Lee's mother's first-hand account of the Holocaust, though he approached the subject in a more generalised way. Quite a feat, all the same, to write a piece powerful enough to carry that weight. "Any time we played it live we never forgot what was about," says Lifeson.

5. TERRITORIES

5. TERRITORIES

(on Power Windows, 1985)

Mid-period, synth-infused Rush at their most bonkers, largely thanks to the crazed Lifeson riff that begins around 1.19, and Lee's stonking, funked-up bass. As ever, Peart was deep in thought, the song an overt critique of cliques, whether nation-sized or much smaller: "In every place with a name/We play the same territorial game."

6. TIME STAND STILL

6. TIME STAND STILL

(on Hold Your Fire, 1987)

Singer Aimee Mann was actually Rush's third choice to duet on Time Stand Still after Cyndi Lauper and Chrissie Hynde, but she proved Lee's perfect foil on a brilliant pop-rock song about fleeting glimpses of beauty.

7. BRAVADO

7. BRAVADO

(on Roll The Bones, 1991)

Bravado wasn't that well known initially," says Lifeson, "but it became a very popular song for us live. I think it has a really beautiful nature to it, and it wasn't necessarily what people expected of Rush." Peart's lyric has shades of Rudyard Kipling's If, and the song's arrangement is just perfect.

8. HEADLONG FLIGHT

8. HEADLONG FLIGHT

(on Clockwork Angels, 2012)

An 11th-hour reminder that Rush could still deliver a dazzlingly virtuoso epic if they put their mind to it, Headlong Flight was manna for Rush fans, offering startling proof that there was life in the old dogs yet. "I wish that I could live it all again," roars Lee on their unwitting last hurrah.