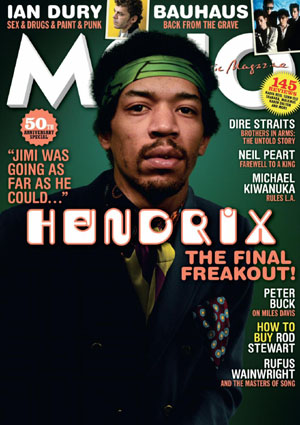

Neil Peart: A Farewell to Kings

Rush's drummer played like a gene-splicing of Moon, Bonham and Buddy Rich, wrote startling lyrics and stayed resolutely himself. After his passing, we pay tribute. Master drummer, questing lyricist, perfectionist and polymath, Rush's Neil Peart left us on January 7.

By Mark Blake, MOJO, April 2020, transcribed by John Patuto

"A BRILLIANT MAN who ruled our radios and turntables," wrote Foo Fighters' Dave Grohl of Neil Peart, who succumbed to brain cancer aged 67. "Not only with his drumming, but also his beautiful words."

Peart was the drummer and principal lyricist of Canadian rock trio Rush. His virtuoso performance and lyrics informed their 1980s hits The Spirit Of Radio and Tom Sawyer, and 18 studio albums, including the multimillion-selling 2112, Permanent Waves and Moving Pictures, between 1974 and 2012.

Rush were a cult band who became platinum artists. Yet despite hit records and arena status, Rush never lost their outsider image. It was something their audience admired and which was partly driven by Peart's restless musicianship, lyrics and world-view. "I've never been happy with anything I've done, but I keep trying," he said, quoting his idol, Buddy Rich.

Neil Peart was born on September 12, 1952 in Hamilton, Ontario, and began playing drums aged 14. He approached it with the same obsessive zeal that he would later apply to other hobbies, including literature and motorcycling. It was a defining Peart trait. "He was weird," said his mother, Betty, in the 2010 Rush documentary, Beyond The Lighted Stage. "He read everything and even learned to knit because he had to know how it was done."

Peart drummed in several local bands before moving to London, aged 18, to further his career. Session work and gigs proved hard to come by and he found work at Carnaby Street jewellers The Great Frog, selling handcrafted rings to visiting rock stars. Peart returned to Ontario 18 months later, taking a job alongside his father at a farm machinery dealership. Then came an offer to audition for Rush.

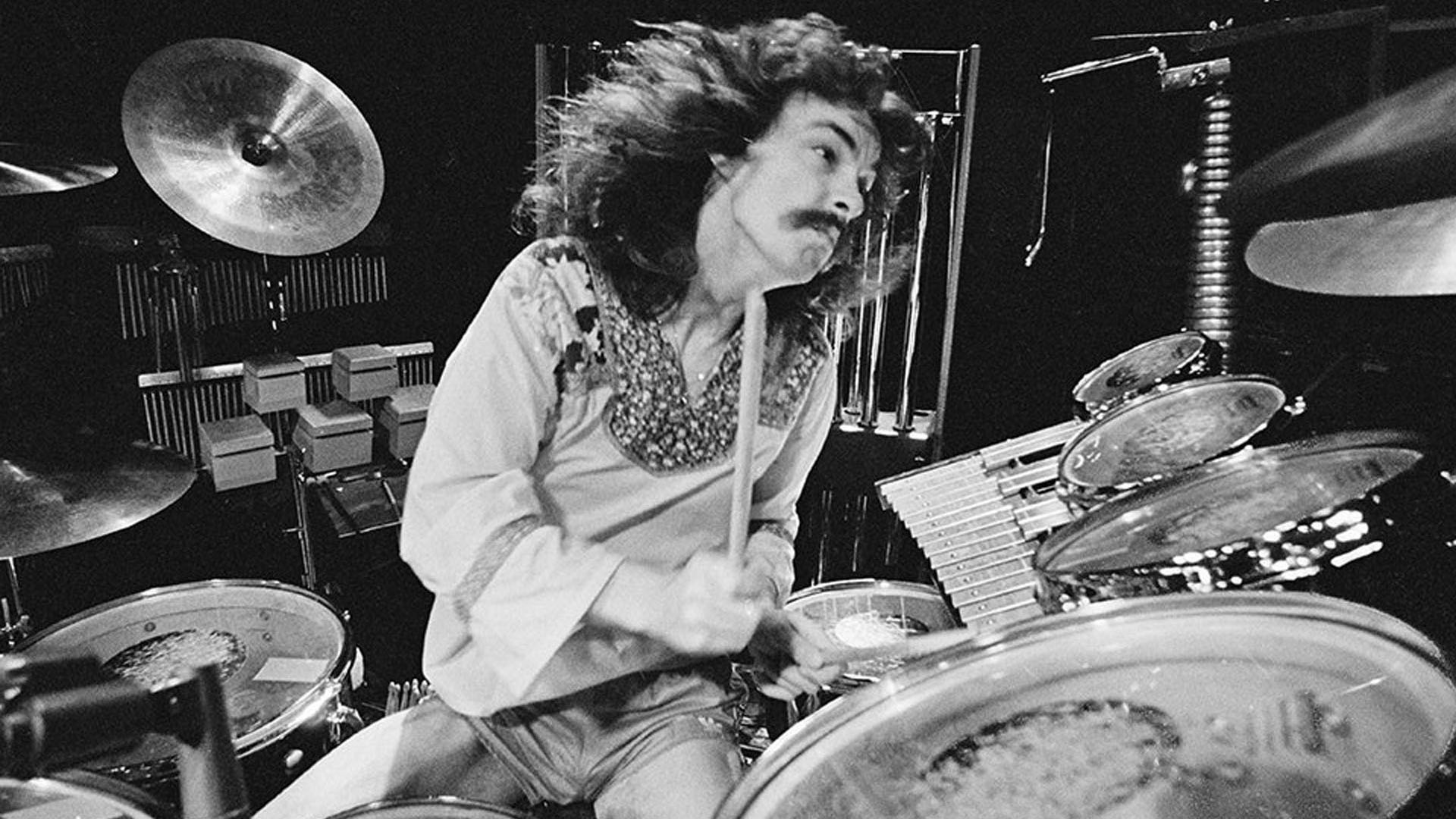

The band, comprising vocalist/bassist Geddy Lee and guitarist Alex Lifeson, had formed in 1968, released one self-titled album and had just fired their original drummer. Peart joined in July 1974, making his Rush debut opening for Uriah Heep at the Pittsburgh Civic Auditorium. "He played like Keith Moon and John Bonham at the same time," recalled Lifeson. "All these insane triplets..."

On the road, Peart read voraciously to fill the time. His bemused bandmates suggested "the new guy" try writing lyrics. Peart debuted as a drummer and lyricist on Rush's second album, 1975's Fly By Night, writing words for its sci-fi centrepiece By-Tor & The Snow Dog, and kickstarting Rush's preoccupation with sword-and-sorcery themes.

Inspired by British prog rockers Yes and Genesis, Peart encouraged Rush to think bigger on third album, Caress of Steel, which included a one-minute drum solo in the six-part suite, The Fountain Of Lamneth. The album bombed, and the band feared they'd be dropped by their label, Mercury Records. Instead, the following year's 2112, Peart's futuristic fable of one man's struggle against a totalitarian dictatorship, based on right-wing philosopher Ayn Rand's novella Anthem, became a Canadian Top 5 hit.

Peart referenced Rand's philosophies again on 1977's A Farewell To Kings and '78's Hemispheres, prompting NME writer Barry Miles to accuse Rush of "preaching what to me seems like proto-fascism." The accusation stung, particularly as Lee and Lifeson's parents were Holocaust survivors. Peart later described himself as "a left-leaning libertarian".

Rush were never critics' darlings, which had the knock-on effect of attracting a large, earnest cult following. At the height of punk, the handlebar-mustachioed drummer wrote lyrics inspired by Samuel Taylor Coleridge's Kubla Khan for Rush's 11-minute party-piece Xanadu, while fans memorised his percussive arsenal ("wind chimes, bell tree, triangle, vibra-slap...") as listed in the gatefold of A Farewell to Kings.

Peart's kit grew bigger with every tour, and most of Rush's 11 live releases included drum solos by the man Lee introduced on-stage as 'The Professor.' Referencing Buddy Rich, Gene Krupa and Keith Moon, these solos were an exercise in what Lee called "power and dexterity". For years, Peart played with his sticks held thick end out down, and he never stopped learning; even taking lessons from jazz teacher Freddie Gruber in the mid-'90s.

The end of the 1970s saw a stylistic shift in Rush's music and Peart's words. Permanent Waves went Top 5 in Canada, the US and the UK, but success came on Rush's terms. Its hit single, The Spirit Of Radio, accommodated Peart's critique of overly-commercialised radio formats, metal riffs, prog keyboards and a mid-song reggae breakdown. "There's no music that can't be Rush music," he cautioned.

However, Peart later cited 1981's Moving Pictures, with its songs about conformism, childhood and mob rule, as the moment "Rush became Rush". The single, Tom Sawyer, included a percussion masterclass: a combination of heart, soul and metronomic precision, with a 180-degree fill mimicked by air drummers at Rush shows forever more. Its lyrics — about a boy on the brink of adulthood — were also compelling to an audience experiencing the same transition.

Moving Pictures was Rush's best-seller yet, but Peart shunned fame and adulation. "I can't pretend a stranger is a long-awaited friend," he wrote in Limelight, before revisiting his days as a school misfit in 1982's Subdivisions ("Be cool or be cast out...").

If Rush were an outcasts' band, then the bashful, deeply reserved Neil Peart was their poster boy.

Throughout the '80s Rush embraced new technology and sounds, alienating some of their existing fanbase. Yet 1984's Grace Under Pressure, while a far cry from 2112, remains a haunting time capsule of period-piece synths and Cold War paranoia, with Peart's lyrics for Red Sector A partly inspired by his bandmates' parents' experiences in Dachau and Bergen-Belsen concentration camps.

Away from Rush, Peart became a common-law husband and father and a keen cyclist and motorcyclist, essaying his travels in four books, beginning with 1996's The Masked Rider. But his personal life was blighted by tragedy. In 1997, his daughter, Selena, was killed in a road accident. Ten months later, her mother, his partner Jackie, died of cancer. Peart detailed the grieving process and a cathartic road trip across Canada and North America in the book Ghost Rider. His bandmates presumed Rush over. "There was no were question of replacing him," said Lee. But Peart married photographer Carrie Nuttall in 2000 and returned to the group two years later.

Rush's stock rose immeasurably in the years ahead. 2010's Beyond The Lighted Stage was a warm-hearted band history, featuring effusive praise from Billy Corgan, Trent Reznor and Jack Black, among others. All reverted to gibbering teenage fanboys when they talked about Peart.

Rush and their drummer's lyrics also almost came full circle. 2012's Clockwork Angels was a self-described dystopian steampunk-inspired concept album, with Peart's words referencing sources as diverse as Voltaire and Cormac McCarthy. But it would be Rush's final studio release.

Peart announced his retirement in 2015. He was later diagnosed with glioblastoma, a virulent form of brain cancer. He lived with the disease for three-and-a-half years, but kept it secret from all but family and close friends until his death on January 7.

Rush started out as a hard rock band, but always refused to be held back by any musical genre or rules. Until the end, both they and their shy, bookish drummer refused to stand still. As Neil Peart wrote in 1987's Prime Mover: "The point of the journey is not to arrive... anything can happen."