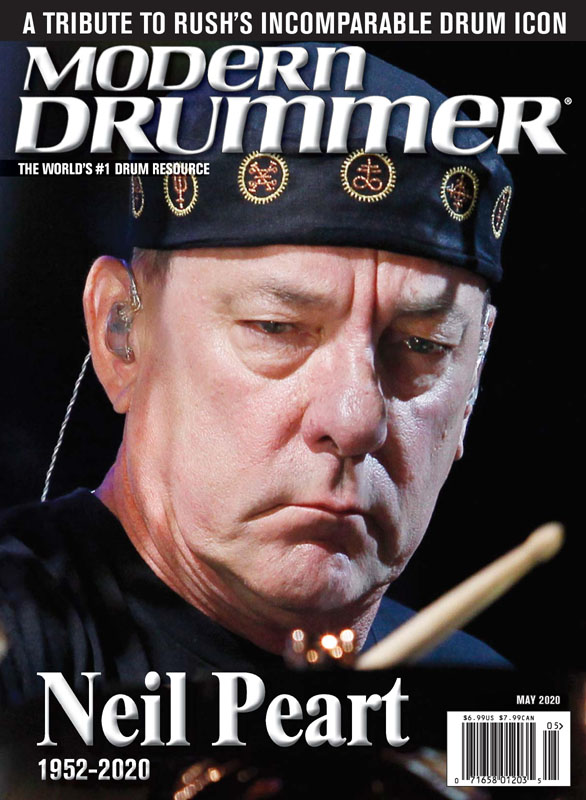

A Tribute to Rush's Incomparable Drum Icon: Neil Peart (1952-2020)

MD pays tribute to the man who gave us inspiration, joy, pride, direction, and so very much more

Modern Drummer, Volume 44, Number 5, May 2020, transcribed by John Patuto

- An Editor's Overview: In His Image

- Reader's Platform: A Life Changed Forever

- Neil Peart Tribute

- Neil Peart on Record

- The Evolution of a Live Rig

- Neil Peart, Writer

- Remembering Neil

- Tributes

In His Image

Role models are a tricky thing. If we're to make our way through life successfully, it's immensely helpful to identify people who have figured it all out. But when you reach a certain age, you realize that "figuring it all out" is a chimera, an unachievable desire that only a narcissist or a lunatic would dare claim. And we begin to perceive what it truly means to be human. We realize that the goal shouldn't be perfection, but rather improvement-of our art, our relationships, our understanding of ourselves. And we come to understand that it's through well-honed skills, hard-earned wisdom, and strength of character that any of us manages to survive in the face of barriers both internal and external, and do it with our humanity intact.

As I write this, a month after Neil Peart's passing, it's strange to say, but his drumming is not at the front of my mind. His humanity is.

Neil was not a magician; he made no effort to mask or hide his rhythmic charms. I agree with those who've suggested that one of the reasons he was so popular was that his drumming ideas were complex enough to intrigue us, but not so beyond our comprehension that we could never imagine figuring them out. They were a gift to us, and a true gift is something that a person can use.

Neil was not a show-off; as active as his playing was, it never overwhelmed the music. "Less is more" was a nonsensical concept to him, at least as some sort of general guideline. (How could you grow up loving Keith Moon and buy into that kind of gobbledygook?) No, he understood that a desire to excite, to entertain, to astound was perfectly human. "Look!" he appeared to shout from behind the drums, "look at this amazing thing I discovered!" Not, "Look at me," but "Look at this." It's not a subtle difference.

And Neil was not a guru. It's a cliché because it's true: The more we learn, the less we know, and Neil seemed obsessed with learning. Moreover, he was not stingy with what he discovered. Those seven books he wrote are not short. And those eighteen albums' worth of lyrics? So many ideas, so much imagery...so many questions! These were not the ramblings of someone who'd "figured it all out." And yet, the confidence with which he shared his ideas-musical, philosophical, interpersonal-was astounding. That confidence, however, was not born from arrogance, but from the knowledge that he put the time and work in to communicate them as clearly and poetically as possible.

Is there a more human activity than to strike an object and marvel at the sound it throws back at us? Is there a more human desire than to tap the shoulder of the person next to us and say, "Hey, listen to this"? Is there a more human pursuit than to keep on hitting that object until you no longer can, because you know that there's no end to the joy it brings you and your fellow man?

And if we believe these things, and want them for ourselves, is there a greater role model than Neil Peart?

Adam Budofsky

Editorial Director

A Life Changed Forever

Modern Drummer readers immediately shared their heartfelt feelings with us when they heard about the passing of drumming icon Neil Peart. One particular letter stood out for us. We think it speaks for a great many of his fans.

Have you ever experienced a moment when you realize your life has changed? A moment that you will forever remember for the rest of your life? Something where you know, right then and there, that your life will never be the same again? A true defining moment. That is what happened when I heard my first Rush song, and the drumming of Neil Peart.

It was during the Christmas break of 1982. I was riding on a high-school bus, returning from one of my first winter track meets. This was an incredible transitional time in my young life. Having been brutally bullied from third grade on, my life was just starting to normalize in high school. For the first time I was part of a school team, and though I had yet to forge strong friendships, I was making acquaintances, and for the first time people were actually cheering for me when I ran races. This was a far cry from being jeered, or worse.

The 1980s were the age of the boom box-huge portable stereos-and we were allowed to bring them to track meets. Blasting them at the back of the bus was a sacred teenage ritual of the time.

I was sitting midway in the bus, lamenting a less than stellar performance in the JV heat of the mile, when something caught my ear. The sound was coming from the boom box owned by Paul Quandt, who was sitting with his friend Rory Martin. The two were "copiloting" the device, the largest in the high school I think, which earned them the seat of honor, i.e., the last seat on the bus. You know, where the cool kids sat.

The song was "The Camera Eye," and by the time it was over, I knew my life had somehow changed. Musically the song was unlike anything I had ever heard. It was the exact opposite of the pop songs of the day. It was over ten minutes long, contained more shifts in tempo than I could keep track of, was sung with a voice that threatened to crack the windows of the bus, and had drum rolls that seemed to move through hyperspace.

Before it ended, I had moved to the back of the bus, a location I had once feared. Somehow I knew it was okay, since I was coming to partake in the music being offered. By the time it was over, the guys (I don't remember any girls back there) were cracking jokes at my newly discovered "air drumming" skills. But this was also different. I inherently knew they were laughing with me, not at me. I also wasn't the only one air drumming that night.

This turned out to be the start of me becoming friends with upperclassmen, and put me on a path to actual friendships for the first time since moving to my mother's hometown six years earlier. Not only did the music and drums affect me, but through the years, Peart's lyrics spoke to me in a way I never thought music could. Within a year, I would go to my first Rush concert with these people (Dave and Ron), and the love of that band would be a common bond with my college and lifelong friends. The best man at my wedding, Keith, and our friends Todd, Jay, Kevin, Pat, Ken, and more all went to Rush concerts together.

In fact, my first Rush concert was in 1984 (the Grace Under Pressure tour) and I never missed a tour after that, concluding with the R40 tour in 2015, Rush's last. Along the way I graduated from air drums (my mother would not allow drums in her house) to drumming magazines, catalogs, buckets, and more. When I graduated with a master's degree, my wife agreed it was time for a drumkit. Though I've never played in a band, I've introduced countless people to drums. In fact, I introduced my nephew at the ripe old age of one. Three pictures that tell the story are one of him at age one on my lap at the drums; one of him at his first Rush concert with me (Clockwork Angels tour), and one of him winning a statewide award for drumming during his senior year in high school. He continues to play, and lord knows he's far better than me.

Thirty-eight years ago I was discouraged and alone, but to quote another Canadian musician, Rik Emmett from Triumph (who were greatly influenced by Rush), "Music holds the secret, to know it can make you whole."* My life changed that cold, bleak winter night, and Neil Peart has touched every part of my life since then, and only in the most positive of ways.

Neil Peart died on January 7, 2020, and a small part of me died as well. I know many who feel the same. I am left with the gift of thirty-seven years of original music that continues to enrich my life to this day. And as Neil wrote so eloquently years ago...

Everyone would gather

On the twenty-fourth of May

Sitting in the sand

To watch the fireworks display

Dancing fires on the beach

Singing songs together

Though it's just a memory

Some memories last forever

Al Prescott

Westford, Massachusetts

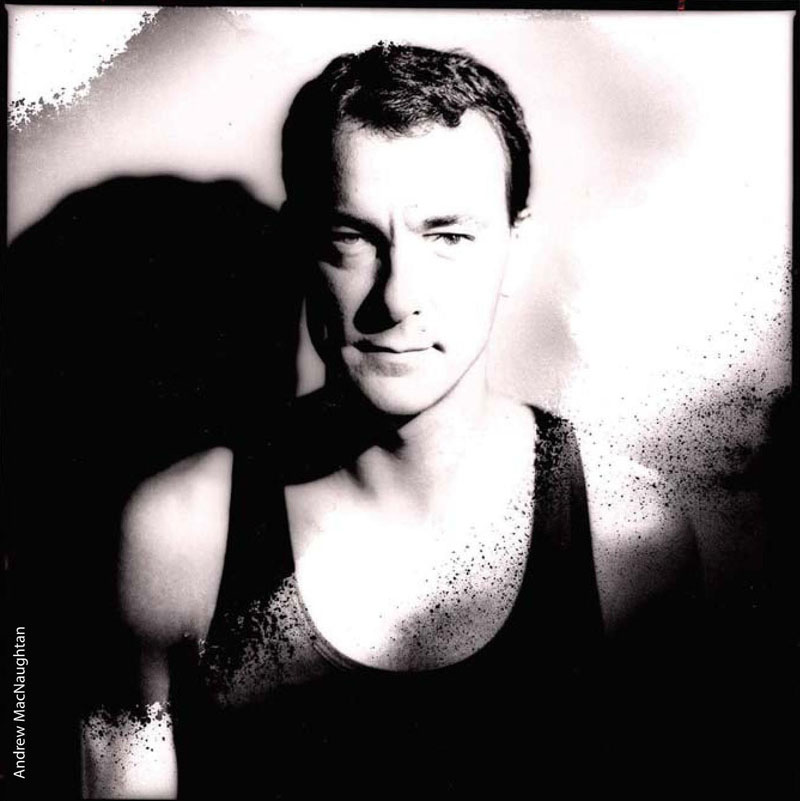

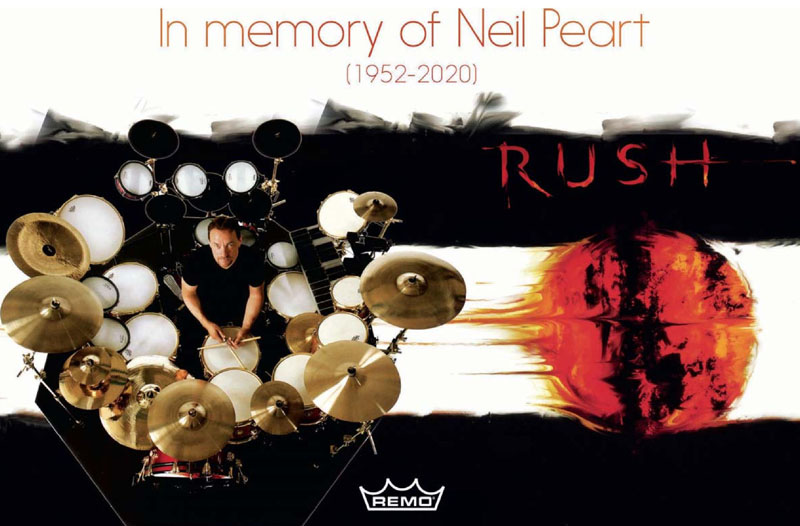

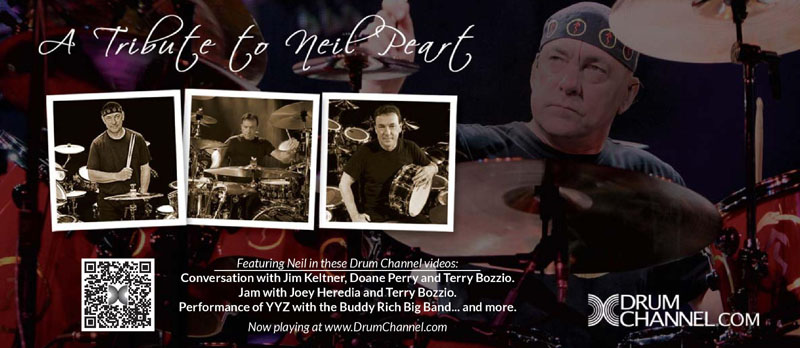

Neil Peart Tribute

Neil Peart, the longtime drumme and primary lyricist for the semina prog band Rush, passed away o January 7 after a several-year battl with brain cancer. He is survived b his wife, Carrie Nuttall, his daughter, Olivi Louise Peart, and hundreds of thousands o fans who reacted in utter shock when th news was made public several days later.

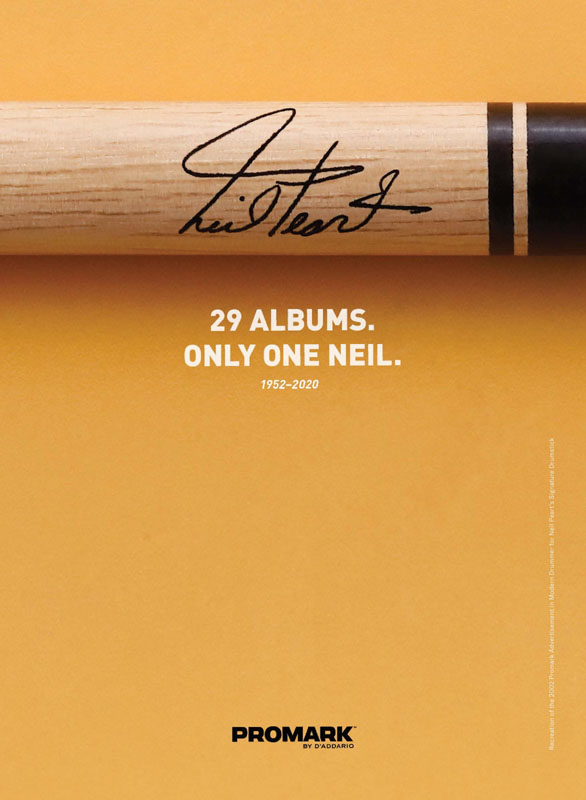

Peart experienced immeasurable success throughout his forty-plus-year tenure with Rush. The group released dozens of gold and platinum albums, was inducted into the American Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and the Canadian Music Hall of Fame, and received numerous Grammy nominations and Juno music awards. In 1983, at the age of thirty, Peart became the youngest drummer to be inducted into the Modern Drummer Readers Poll Hall of Fame. And in 2014, a survey of MD readers, editors, and professional drummers ranked Peart third among the fifty greatest players of all time-behind only Buddy Rich and Led Zeppelin's John Bonham.

It's easy to see why Peart ranks so highly among the legends. His playing on Rush songs like "Freewill," "Limelight," and "Subdivisions" inspired generations of drummers to pick up the sticks. He was a master at making odd time signatures feel right at home on an FM dial. And while Peart didn't invent the rock drum solo, he certainly refined and expanded the art over the years touring with Rush. Devotees pore over the evolution of "the Professor's" elaborate live drum setups. And even those who've never sat down at a kit found themselves air-drumming to Peart's parts.

Peart was born on September 12, 1952, in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. He started playing drums as a child after picking up a pair of chopsticks and banging on his sister's playpen. When he was thirteen his parents enrolled him in drum lessons. At eighteen he moved to England to pursue music, but left two years later to return to Toronto. In 1974, after playing part-time in various local bands, Peart auditioned for Rush. The next forty years yielded dozens of albums, live performance videos, sold-out shows, and tens of millions of albums sold. The drummer took a hiatus from the group after tragically losing his first daughter, Selena, in 1997, and then his first wife, Jacqueline, in 1998. Peart returned to the band in 2002 after remarrying, and continued playing until his retirement in 2015.

An avid motorcyclist, Peart was known to ride his bike alongside the Rush tour bus from venue to venue, and the drummer's passion for literature inspired him to author seven nonfiction books about his travels and life. In 1994 he produced a tribute album to Buddy Rich, Burning for Buddy (a second volume came out in 1997), and throughout his career he contributed to numerous educational books and DVDs. With Rush, Peart's philanthropic pursuits included fighting cancer and other diseases, advocating for human rights, and raising funds for disaster relief and music education.

Peart's deep and thorough insight into drumming and life in general has graced the pages of MD dozens of times since he first appeared on the magazine's cover, in 1980. So perhaps it's no surprise to find, in a 1984 MD feature, this response to a question about what he thought his purpose in life was: "You can ask those questions, but what's the point? The point is I'm here and making the best use of it. Why am I spending my life in this particular manner? Most times that tends to be a combination of circumstances and drive. The fact that I wanted to be a successful drummer was by no means a guarantee that I was going to be. But circumstances happened to rule that I turned out to be one."

To honor Neil Peart's musical contributions-and the outsized influence he had on so many people, in so many forms-we begin by examining the music he made with the progressive-rock band Rush, pointing out highlight moments on each and every studio album they recorded with him, from their 1975 sophomore set, Fly by Night, through 2012's Clockwork Angels

Later we trace the evolution of his famous drumsets via several of Rush's iconic live albums, and then survey the popular books he wrote during his lifetime, a "side career" that Neil took to with the same energy and thoughtfulness that he approached his playing and...well...everything else that interested him throughout in life.

Finally, we hear from the pro drummers: some household names, others less famous, but all profoundly influenced by their exposure to Peart's life's work. All have a unique tale to tell, but also share with their peers an utter respect not only for Neil's artistic accomplishments, but for his humanity, and the role that he reluctantly yet brilliantly played as representative to the world of the power and glory of drumming.

Neil Peart on Record

Ilya Stemkovsky

Rush came to prominence in the mid-1970s and quickly rewrote the rock music rulebook. Marrying the expansive concepts of the great British progressive-rock bands to a decidedly North American hard-rock aesthetic, Rush initially focused on complex song structures and instrumental pyrotechnics, in the process raising the performance bar for rock musicians and blowing the minds of their followers.

By the early '80s, influenced by the sounds of new wave and other contemporary styles, Rush tightened their arrangements, wrote progressively stronger hooks and melodies, and incorporated more contemporary musical elements, all the while continuing to up the rhythmic ante. This unusual recipe found a welcoming audience on FM radio with slick yet sophisticated releases like 1980's Permanent Waves (featuring their breakout track "The Spirit of Radio"), '81's Moving Pictures ("Tom Sawyer," "Limelight"), and '82's Signals ("Subdivisions," "New World Man").

Through a series of classic records featuring brilliant, cerebral, and yes, busy drumming, Neil Peart ascended to the throne, inarguably becoming the most popular drummer on the planet. Importantly, each new Rush album documented the creative progression of a drummer who never stopped challenging himself-and, by extension, us. Here we trace that progression by homing in on Peart's work on each of the band's studio albums. Strap yourself in: it's going to be quite a ride.

Fly by Night (1975)

Fly by Night (1975)

Caress of Steel (1975)

Caress of Steel (1975)

2112 (1976)

2112 (1976)

A Farewell to Kings (1977)

A Farewell to Kings (1977)

Hemispheres (1978)

Hemispheres (1978)

Permanent Waves (1980)

Permanent Waves (1980)

Moving Pictures (1981)

Moving Pictures (1981)

Signals (1982)

Signals (1982)

Grace Under Pressure (1984)

Grace Under Pressure (1984)

Power Windows (1985)

Power Windows (1985)

Hold Your Fire (1987)

Hold Your Fire (1987)

Presto (1989)

Presto (1989)

Roll the Bones (1991)

Roll the Bones (1991)

Counterparts (1993)

Counterparts (1993)

Test for Echo (1996)

Test for Echo (1996)

Vapor Trails (2002)

Vapor Trails (2002)

Snakes & Arrows (2007)

Snakes & Arrows (2007)

Clockwork Angels (2012)

Clockwork Angels (2012)

With Peart's passing, Clockwork Angels became Rush's final studio statement, and with it they and Neil went out on top.

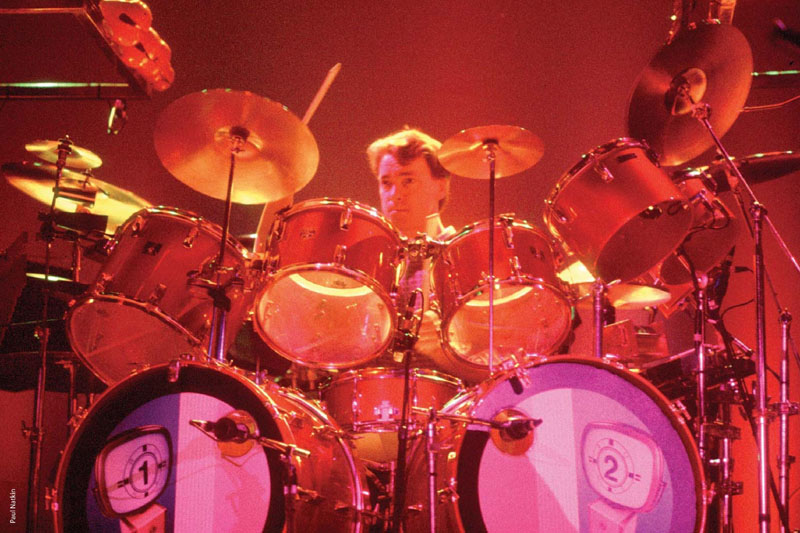

The Evolution of a Live Rig

By Ilya Stemkovsky

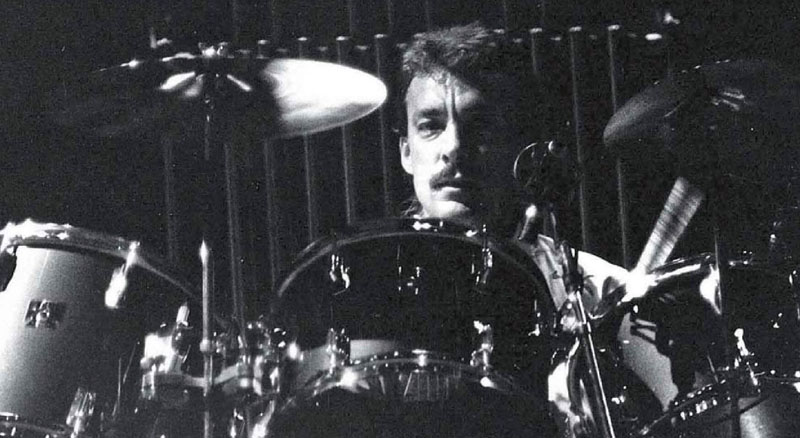

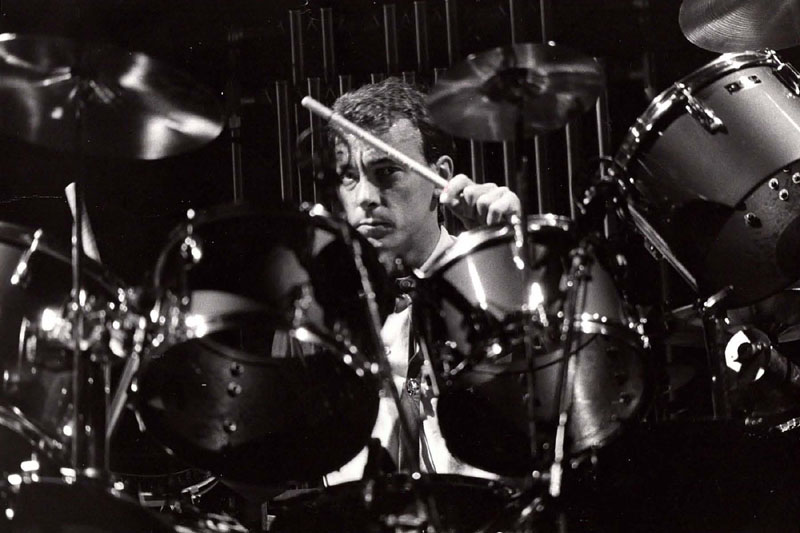

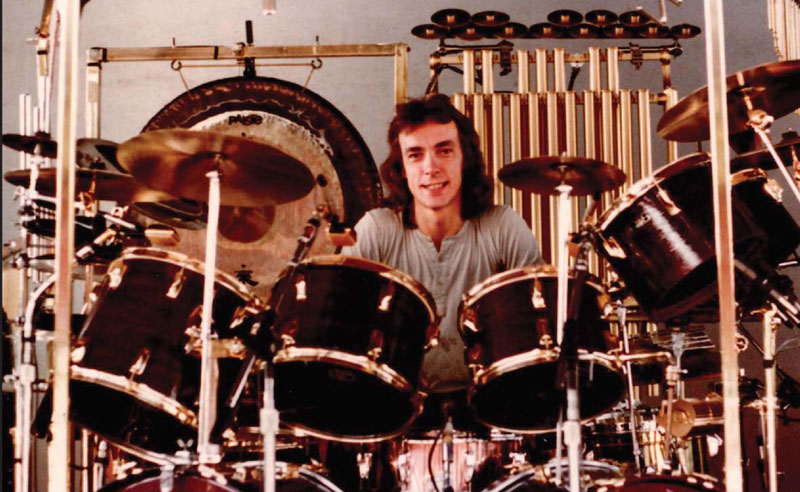

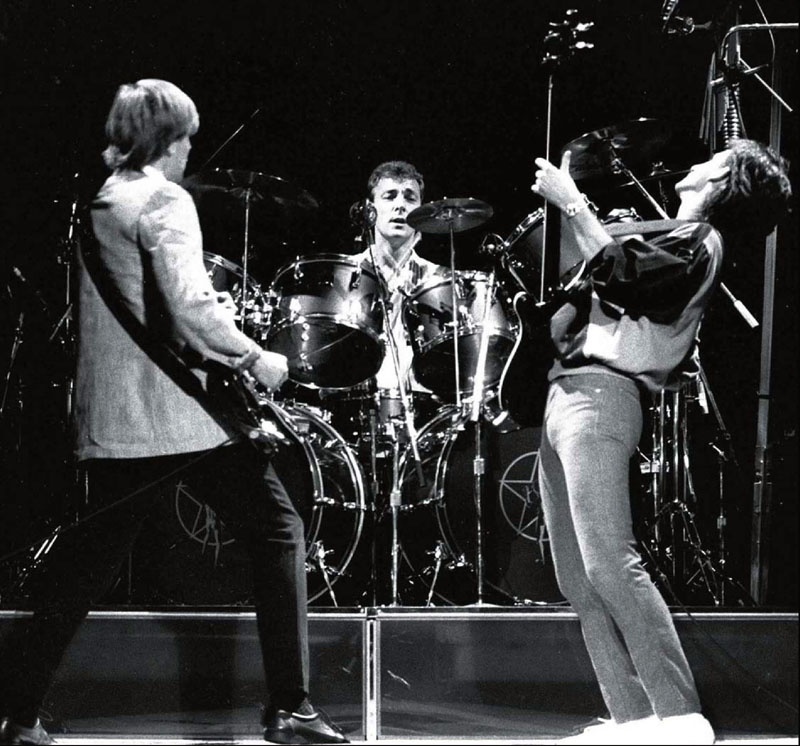

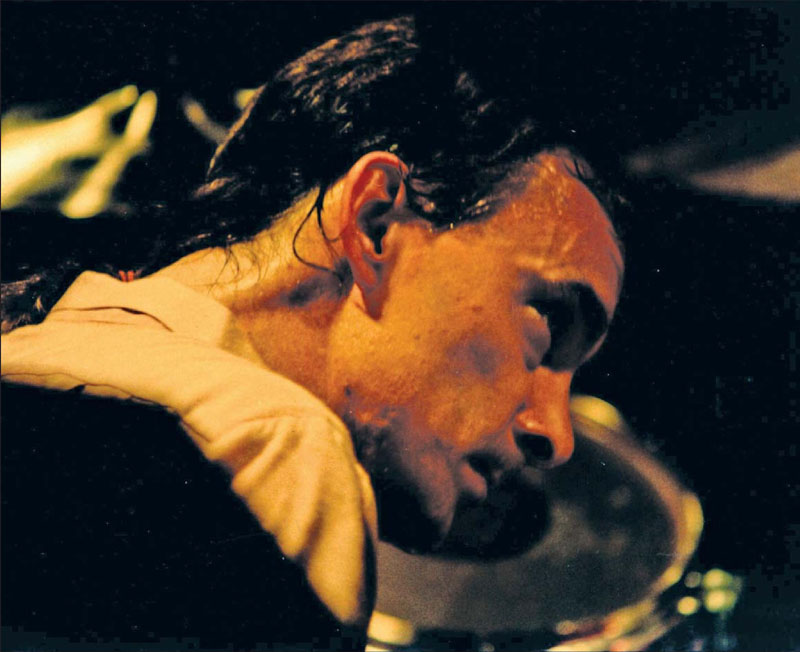

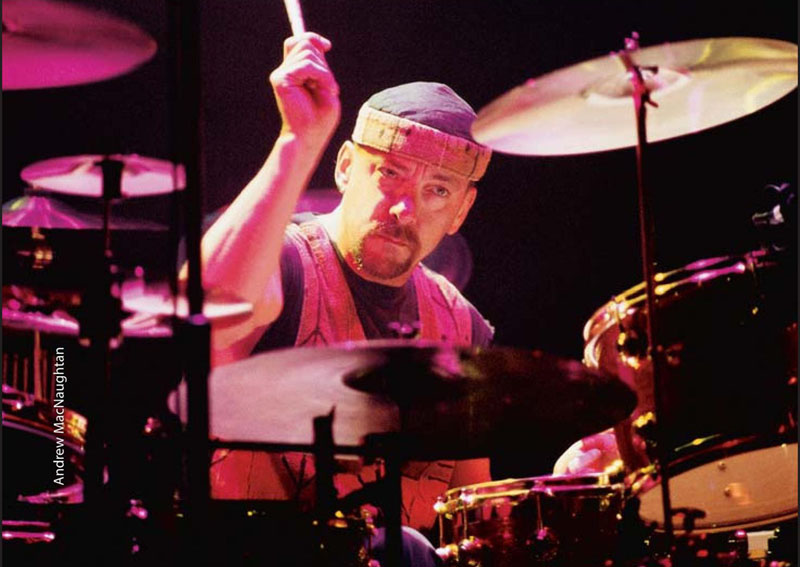

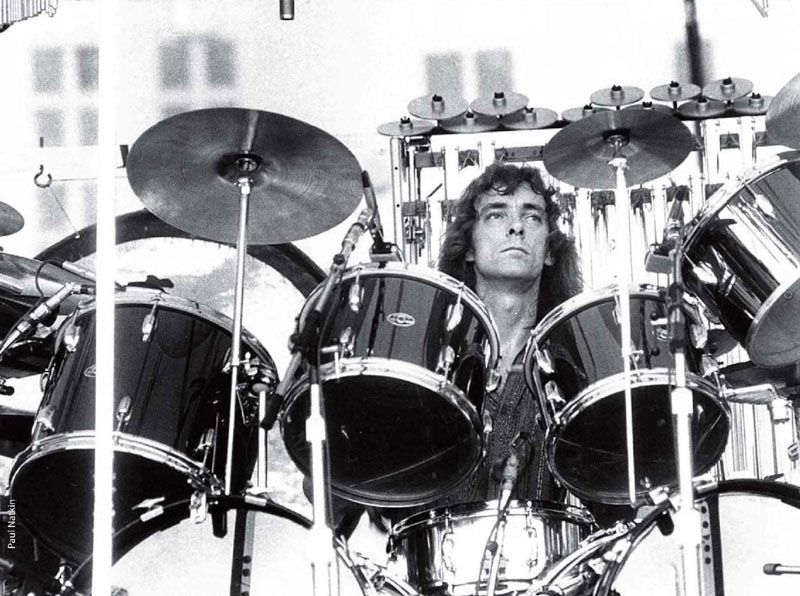

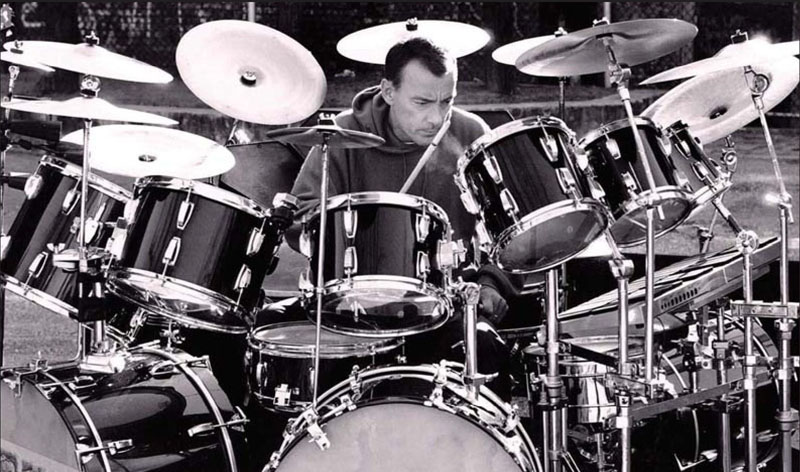

Neil Peart played a number of different kits during his forty years of touring with Rush. Here we discuss the major evolutionary changes his kit went through by focusing on the setups he sported during the first three, classic Rush live albums plus the unique approach he took during their R40 tour.

All the World's a Stage (1976)

All the World's a Stage (1976)

Exit...Stage Left (1981)

Exit...Stage Left (1981)

A Show of Hands (1989)

A Show of Hands (1989)

R40 Live (2015)

R40 Live (2015)

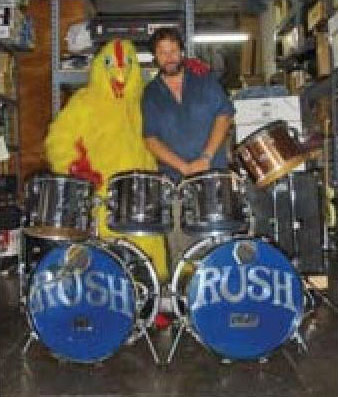

The Story Of Chromey

In 1987, Modern Drummer held a contest where entrants were instructed to send in a two-minute, unaccompanied drum solo on cassette, to be judged by none other than Neil Peart himself. The 1,776 entries received were whittled down by MD's editors to 46, from which Peart chose the winners. And the prize? It sounds too good to be true, but the three top winners would each receive a kit that Peart had recorded with and used in live performances throughout Rush's career. (Unable to keep his winners to three, Neil asked his cymbal company at the time, Zildjian, to put together a fourth prize package, a set of new cymbals.)

Perhaps Neil's most famous kit, the Slingerland Chrome set he used on the recordings and tours for Fly by Night, Caress of Steel, 2112, and All the World's a Stage-yes, the drums on the cover of that seminal live album-were won by a drummer named Mark Feldman. Now cut to sometime in 2009, and MD photographer John Fell, who at the time was a partner in Brooklyn music store Main Drag Music, was visited by Feldman, who wanted to sell the kit on consignment. Fell, who'd worked in museums prior to entering drum retail and repair, discussed with his colleagues what to do with the kit and how to sell it. "The enemy of conservation is restoration," says Fell. "But since we were selling it, we decided to keep it as is-not even conserve it, let alone restore it. It was even in Neil's tuning."

There was a long, intense eBay auction, which resulted in some Rush fans asking to see and touch the kit, and the store decided that it needed to be put on display. In one particularly odd wrinkle to the story, Fell received multiple phone calls from an anonymous shadow figure calling himself "the High Priest from the Temple of Syrinx," who insisted that the kit wasn't authentic. The bidding price froze at $2,112 (of course), and then $21,012, and the drums eventually sold for around $25,000.

And who showed up to pick up the kit? A collector named Dean Bobisud, who drove all the way from Chicago. "He owned a pizzeria, and he sold a Corvette to do this," says Fell. "He was a serious Rush fanatic, with a shrine of Peart's sticks and guitar picks. He arrived in a van with a bunch of matching drum bags, and was very excited. He even put a chicken suit on for the photo-the actual chicken suit that Rush's crew used onstage during their tours. They'd have rotisserie chickens turning onstage, and techs wearing these suits would come out and baste them." The kit was eventually restored and has since made the showcase rounds, as documented on the internet.

It seems that, indeed, all the world's a stage, and some of us are merely players... wearing chicken suits.

Neil Peart, Writer

By Ilya Stemkovsky

It would make sense that Neil Peart's forays into prose writing would be of a remarkably high standard, not only because he was such a brilliant lyricist, but because he was such an able craftsman. Like his meticulously constructed drum parts, Peart's books are the work of an artist paying close attention to detail while he composes something to make you think and also feel.

That word, "compositional," which is so often used to describe Neil Peart the drummer, also applies to his written word outside of the songs he wrote for Rush. A quick internet image search of the band in the 1970s will yield multiple photos of Peart's face buried in a book of some sort, and aside from his own pure enjoyment, it was years of study of countless writers that led the drummer/lyricist to eventually try his hand at becoming an author.

And if Peart's songs tackled everything from fantasy to technology to religion to relationships, and everything in between, his seven books, inspired mostly by his adventurous excursions by bicycle and motorcycle between Rush tours, paint the picture of a more or less independent inland traveler, all-too-human, dealing with life's mysteries and tragedies and beauty. For those looking to go beyond the lyric sheet, below is a quick guide to the Professor's excellent output of books.

.jpg) The Masked Rider: Cycling in West Africa (1996)

The Masked Rider: Cycling in West Africa (1996)

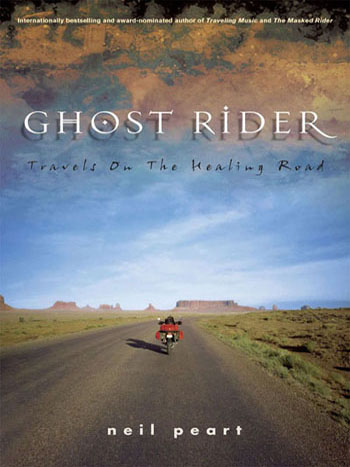

Ghost Rider: Travels on the Healing Road (2002)

Ghost Rider: Travels on the Healing Road (2002)

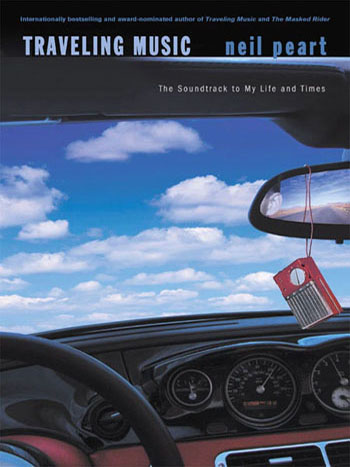

Traveling Music: Playing Back the Soundtrack to My Life and Times (2004)

Traveling Music: Playing Back the Soundtrack to My Life and Times (2004)

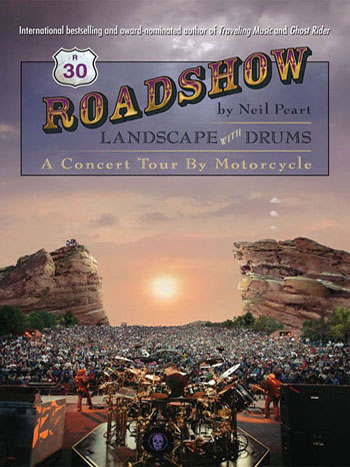

Roadshow: Landscape with Drums: A Concert Tour by Motorcycle (2006)

Roadshow: Landscape with Drums: A Concert Tour by Motorcycle (2006)

Far and Away: A Prize Every Time (2011)

Far and Away: A Prize Every Time (2011)

Far and Near: On Days Like These (2014)

Far and Near: On Days Like These (2014)

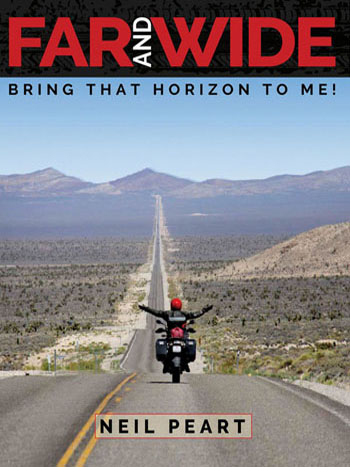

Far and Wide: Bring That Horizon to Me! (2016)

Far and Wide: Bring That Horizon to Me! (2016)

Remembering Neil

To truly have your own voice on an instrument is one of the greatest achievements a musician can have, and Neil Peart had just that. He also had his own voice as an author and lyricist who was a master storyteller, an architect of dreams, a teacher, a sage, an explorer-and I think the outpouring of grief that was experienced at the news of his passing went beyond just the loss of a fellow drummer. We "knew" him through his written words, whether it be from the music or his non-fiction work. The loss of his person was felt on a profound level. He inspired millions as a wordsmith extraordinaire, and his playing "just sounded cool." And by that I mean, you can't just decide to be cool. Cool is. Or it isn't. And his playing was cool and spoke to musicians and the layman alike. The Rush records were always mixed with the drums equal in the blend-you never had to listen while squinting from the edge of your seat to decipher what he was doing through a cacophony of reverb or a wall of other instruments. His playing, like it or not, spoke with the clarity of his written words.

I only met him once. We were working right next to each other at Ocean Way in Los Angeles. He was recording the "Hockey Night in Canada" theme and I was recording with Brian Wilson on his Gershwin record. Sabian's Chris Stankee pulled me next door to meet him, and there was a full big band and a film crew, along with the actual Stanley Cup trophy. I found him to be kind, engaging, and warm. After a while he was asking me all the questions in our conversation-about what I was doing, what it was like working with Brian Wilson, and whatever else was coming up in my schedule.

One of the definitions of the word "gentleman" is someone who makes you feel at ease, accepted, and in good company. Neil was a gentleman indeed. I wish I would have had the chance for another encounter with him, but I'm grateful for the lovely one that I had. I wish he would have been able to enjoy his retirement, especially after living through such unimaginable tragedy. He was an important figure during my school years in real time '76 to '82, basically 2112 through Signals. Moving Pictures and Signals can catapult me back to junior high school in my mind more powerfully than a photograph. I think many of us feel that way, and his contributions to music and literature will live within us all.

Todd Sucherman (Styx, sessions)

The first big concert I ever attended was Rush during their Roll the Bones tour. It was the first time I saw a band in an arena, and it was the first time I ever saw a live drum solo. Needless to say, it blew me away. It sparked a lifelong flame that I've carried through my career to this day. Neil was one of my absolute biggest influences, and his drumming inspired so much of how I've developed as a drummer. He was and will always be a pillar of this fantastic drumming community for countless reasons. But one specific reason in my mind is that he was and will always be at the center of so many conversations between drummers-and non-drummers-of all ages, all skill levels, and all styles of music. He brought people together because of drumming and helped them fall in love with this incredible instrument. Neil Peart was the "gateway drummer" for me and many others, and he'll continue to be that kind of legend for the rest of time.

Matt Halpern (Periphery)

My first concert was Rush at the Cow Palace in San Francisco, 1980, on the Permanent Waves tour. I was twelve. My older brother had first played me 2112 and A Farewell to Kings when I was ten. It was "Xanadu" that got its hooks in me first. Neil's multi-percussion sound world and his effortless odd time signatures fascinated me. It was so cinematic. His lyrics were the script. Lying on the floor listening to it in the dark or staring at the gatefold sleeves had a profound impact on my life that I would only come to realize much later, when I transitioned from being a drummer in a band, living in the limelight, to being a film composer. Once-mystical devices like the vibraslap, crotales, temple blocks, orchestra chimes, and tubular bells now play an everyday role in my film music.

As a high school sophomore, I was given an English assignment to write and send a business letter to any business that interested me. Since the only business I cared about was drumming, I wrote to Neil Peart and sent it in care of Modern Drummer. I wasn't expecting a reply, but there in my mailbox right around Christmas vacation 1982, roughly nine months later, a postcard from Neil arrived. I couldn't believe it! I stood by the mailbox in disbelief, reading and rereading Neil's handwritten responses to my questions. I must have read it a hundred times that day. I promptly wrote him back, and again nine months or so later he replied with another handwritten postcard! In both incidences Neil stressed to find and be myself. To "try and do everything, and find out what you do best!" Obviously, based on my questions, I was trying to imitate him. I was fourteen and had no idea who I was. I wanted to sound like him, but it hit me and it stuck, perhaps because he underlined the word "you." It may have taken me a while to find my own voice (still in progress), and I certainly borrowed from Neil along the way, but that was the best career advice I was ever given. I have never forgotten it. I pass it along to any hungry musician that asks me for advice.

The inspiration, compassion, and personal encouragement that Neil so graciously gave to a fourteen-year-old kid from rural Northern California has helped fuel my passion for music and quest for originality to this day.

Thank you, Neil Peart. You will forever be in my heart, in my hands, in my feet, and in my ears. Rest in peace.

Brian Reitzell (film composer, percussionist)

My world changed the day I heard Neil for the first time. My cousin played Exit...Stage Left for me when I was twelve or so, and when I heard the drum solo on "YYZ" my wheels turned so hard that it felt like my brain melted on the spot. I wanted to sound like Neil. I wanted to play the same drumset like Neil. I wanted to be Neil. I know I'm the norm rather than the exception, as Rush left their indelible mark on so many fans and musicians through the years-especially drummers-because of their talent, originality, and world-class musicianship.

It was hard for me to get out of my Rush/Neil phase. I couldn't get enough of the music and the drumming. My playing has changed and evolved a lot through the years, but I still find myself channeling his wit, smarts, and compositional skills on the kit. He left me a huge gift, and I will forever be thankful for it. He might be gone, but he's surely not forgotten.

Antonio Sánchez (Migration/Bad Hombre)

In 1981 I was a brand-new drummer. My ears were searching for inspiration. I had heard "The Spirit of Radio," but it was still a bit of an underground thing here in L.A. Seemingly out of nowhere Moving Pictures dropped, and like most drummers I was flabbergasted. Brave, technically challenging, musically beautiful, sonically delightful, this record changed the game. I was already a fan of Phil Collins, so odd meter wasn't new, but this was different. It felt comfortable. Every day in the bedroom, testing my mother's patience, I worked on "YYZ," "Tom Sawyer," "Red Barchetta," and "Limelight." Not sure why I needed to know these songs, but determined all the same. Then one day I was asked, almost forced, to play at my junior-high talent show. I accepted, but it's as if my classmates chose the song. It had to be "Tom Sawyer." If you can play "Tom Sawyer" then you're a pro. Never mind the gigs I was already doing. I was being put to the test. Play it I did, and the kids loved it. There is something about playing in front of your friends that can play games with your nerves.

Neil set the bar so high, it seemed or seems unreachable, but he did it with grace and humility just to give us hope. Now with a career entrenched in the progressive-rock scene, I understand why I had to know those songs. I was in school with the Professor.

Jimmy Keegan (Pattern-Seeking Animals)

One of my earliest memories is drumming to "Tom Sawyer" on the seats of my mom's car on the way to daycare. Even as an eight-year-old, it was apparent to me that Neil's drumming was something special, powerful. He was the spark that lit a lifelong fire for the drums and music. I'm not alone in this realization. That young boy from Iowa could never have imagined the friendship to come with Neil Peart. He shared his adventures motorcycling, sailing, touring, and drumming. Every day ended with a Macallan and lots of laughter. More than all this, Bubba was there for me when my own dad died of cancer. He brought me In-n-Out after I got creamed on my motorcycle. He'd meet with Make-a-Wish kids in secret, play drums with them, and take them for milkshakes. He was that kind of dude. Extraordinarily kind, even after the universe took everything from him. He left our world a better place than he found it.

The measure of a life is a measure of love and respect,

So hard to earn so easily burned

In the fullness of time,

A garden to nurture and protect

(It's a measure of a life)

The treasure of a life is a measure of love and respect,

The way you live, the gifts that you give

In the fullness of time,

It's the only return that you expect

Neil wrote these lyrics for the last song on the last Rush album. To the last...you measure up, Bubba.

Chris Stankee (director of artist relations, Sabian)

During the last three and a half years, Neil faced this aggressive brain cancer bravely, philosophically, and with his customary humor, sometimes light and occasionally dark-all very characteristic of him, even given the serious situation and the odds handed to him at the time of the diagnosis and subsequent surgery. But he fought it.

His tenacious approach to life served him well during these last years, and although he primarily kept his own counsel, he retained his dignity, warmth, compassion, understanding, and generous, deeply inquisitive nature, which never deserted him. He was cogent right up until the end, and miraculously, he really had no pain-a blessing for which we were all profoundly grateful.

The outpouring of love, respect, and appreciation from every imaginable quarter for this beautiful man and extraordinary, singular talent, graced with a mind like no one I have ever met, is touching beyond words. To those that had to guard and hold onto this information closely for three and a half years, for obvious and protective reasons-his wife, Carrie, daughter, Olivia, his loving family, bandmates, friends, and colleagues-they have my undying admiration.

Apart from his deeply gifted, genius talent and prolific output, which he brilliantly displayed through music, lyric, and prose writing, and that staggering storehouse of knowledge across an array of subjects in multiple fields, he remained a kind, gentle, considerate, and modest soul and a consummate gentleman. I think I speak for all, known and unknown to him, to say he will be deeply missed, eternally loved, appreciated, and remembered for his many invaluable contributions to music, art, and the written word. Those will be forever celebrated.

Thank you, my dear friend, for passing this way. We are all richer for your presence and light in our lives.

Doane Perry

It's extremely hard to put into words exactly how much Neil Peart meant to me as a fan, a drummer, and lastly a friend. It's even harder now, as I write this on the heels of yet another stellar drummer, major NP fan, and good friend Sean Reinert's passing, one week after Neil's. So this piece is written also with Sean in mind, because Sean influenced tons of up-and-coming metal drummers, the way Neil touched us as players a few decades prior. And both men were stellar human beings and kind souls who I miss very much as I type this, trying to hold the tears back.

Neil Peart is my favorite drummer and always will be, and my first-ever contact with him was when I wrote him a fan letter in care of Modern Drummer back in 1985, which was a kind of secret way to contact the ever elusive NP that some of us heard about as kids in the '80s. I was lucky; he got my letter and returned a postcard packed with all the answers to my questions, and he wished me "all the best." The fifteen-year-old kid sat in his driveway-actually it's still my driveway-looking at "the Golden Ticket": "Oh, I can't wait to show all the drummers in band tomorrow," I gloated, and boy did I. That postcard sat on my dresser for about three years before I went off to Berklee, and I sealed it in a photo album for preservation.

Many years later, after I became a "known" drummer, I had mentioned to drum tech Lorne Wheaton at a NAMM party in 2006 or 2007 that I would really love to meet his boss, if it was at all possible, and he told me, "Next time we come through, text me. Don't worry, he knows who you are." "What! Neil knows who I am?" "Yes, dude, trust me, he knows who you are!" I was floating on air just knowing the fact that maybe I might have been on his radar. The next time Rush came through town, thanks to Lorne and Rob and Paul from Hudson Music, I was in the dressing room, with my wife, shaking hands with "The Professor." (Here come those tears....)

It was the moment I'd waited my entire life for. Mike Portnoy had told me a few hours prior, "Don't talk about drums unless he does first," but I knew this very important tidbit of info going into the meeting. So did Neil talk about drums? Not only did he talk about drums, he showed me what he was working on with Peter Erskine at the time on his practice kit. This is when he's supposed to be warming up, but no, he's taking that precious time before his show to show me what he's working on. Blew my mind, still does just talking about it. After that I pulled out my Slingerland Artist model snare for him to sign, and he goes, "I used to play one just like this." "Yes, sir, I know, that's why I have one!"

It was one of the greatest days of my life, and every tour after that he always took care of me with tickets and passes for any show I could make it to. Even when I was on the road, he would extend the invite down to my wife and family. I was now in the "inner circle."

On another tour, we sat in his dressing room discussing his book Road Show and the death of Dimebag Darrell from Pantera, whom he writes about in that book. Neil never knew that I was on that tour with Dime and Vinnie up until a day prior to the shooting, and he knew how much talking about this was kind of upsetting to me, because obviously he knew I might not be sitting there talking to him if that had happened a day or two prior. He put his giant hand on my shoulder and said, "Let's talk about something else." He knew he'd struck a nerve, and he wanted our meeting to be a happy one. I told him I was very happy he wrote about my friend, and I told him how much his friendship meant to me. I never once said to him, "Dude, you're my favorite drummer." I didn't have to. When we left him to do his warm-ups, I thanked him as usual, went to shake his hand, and then he brought me in for the "Bubba hug."

The last time I spoke with him was over the summer. Michael (Neil's longtime right hand man) had called me to ask a few questions about something, and I said, "Hey, is Bubba with you?" and he goes, 'Yeah. he's in the other room." I just told him, "Give him a hug for me." A few minutes later the text "big hug back" came in. That's how I want to remember my hero-not because he was one of the greatest ever to pick up sticks, but because he was a genuine, awesome guy.

Jason Bittner (Overkill, Shadows Fall)

I can't think of a drummer that had a bigger influence on me than Neil Peart. As a kid I was fascinated by his equipment and setup onstage. Of course my first drumset had to be red as well; that was the color that Neil's drums were. I strived to make my kit bigger and bigger, until I actually had to routinely schlep my drums to rehearsals and shows. At that point my kit got smaller and smaller.

If I think about the thing that I learned the most from Neil, it was that the drums were a compositional element. The drum part mattered as much as any of the other instruments. But it didn't hold that weight automatically; you had to make it count. There was a heavy responsibility on the player to hear that call and then meet the challenge of making your part worthy of the music you were contributing to. Neil reminded us that we are not the "time keepers," we are songwriters. We just happen to be sitting in back, behind the drums, when we compose.

Chris Prescott (Pinback)

A good friend in high school named Mark Casey once gifted me every Rush album (on vinyl) from Rush to A Show of Hands. That's fifteen records! At the time, Mark and I were in a punk-rock band together, but he said, "I see that you're getting serious about the drums. Check this guy out!" The songs were fascinatingly long, and complex, with multiple time signatures. But still, everything made sense. Neil Peart's drum parts were remarkably well thought out. The sounds were crisp. The patterns were super creative. Then I got a chance to see the band live on the Presto tour. Neil pulled off every single note without a hiccup. And as I looked around, I found myself sitting in an arena filled with fans air-drumming all the signature fills, accents, and breaks.

Shall we take a moment to talk about Neil's lyric writing? Unique and intelligent! For a teenage listener trying to find his or her way in life, "Subdivisions," "Freewill," and "The Spirit of Radio" were such thoughtful masterpieces.

Although Neil and I endorsed many of the same drum/cymbal/head companies, I regretfully never got to know him. I always felt an urge to respect his privacy, which I was told was an essential part of him. But from what I've been told by close colleagues, Neil was one of the kindest, most humble people in our drumming community. He was also a total legend. While we strive to make ripples in the world of music, Neil Peart was a massive shockwave. Thank you for everything, Neil.

Brendan Buckley (Shakira, Perry Farrell, Tegan & Sara)

There are two events in my life that led me to choose drumming as a career. First, seeing Gregg Bissonette give a drum clinic in January of 1989, and second, seeing Rush on the Presto tour on June 22, 1990. I will never forget the feeling that these two events gave me at twelve and fourteen years old. They were both overwhelming experiences, and I remember after both saying to myself, "That's it. I want to do that for the rest of my life. I want to be those guys." The Rush show sealed the deal for me.

I became completely obsessed with Rush, learning every note of every tape, wallpapering my room with posters, getting all of the tour books, pins, and patches, constantly writing down all of the albums in chronological order anywhere I could-usually on friends' notebooks. To me there is absolutely nothing in the world like seeing them live. (I got into Frank Zappa around the same time, but sadly, was never able to see him live.) I was lucky enough to see Rush live twenty-four times, and each one was a truly magical experience. I get goosebumps even thinking about going to see them.

Like so many others, Neil's influence runs deep to the core of who I am. I would not have become a professional musician if it were not for Neil's profound influence on me. Which means I would not have gone to Indiana University, where I studied music. Which means I would not have met my wife, possibly not become a father, and probably not live in Los Angeles. My life revolved around Rush and Frank. RIP, Neil, and my deepest condolences to his family and friends.

Ryan Brown (Dweezil Zappa)

Neil changed the world of drumming forever. What an amazing player; what a fantastic band. He was a good friend and an incredible man. We used to play double drums at my house, and I remember asking him one day, "What do you feel like jammin' on today?" He replied, "Can we just focus on playing in 3/4?" So, we played tunes that were jazz waltzes in all the tempos we could think of, and we traded and had a blast expanding vocabulary in 3/4. He was always wanting to push himself and further his knowledge...he had such a strong passion for playing drums.

Even though he had never met my dad, Bud Bissonette, Neil showed up at his memorial service because he knew we had such a close father/son relationship. That always meant the world to me. That's the kind of guy Neil was. Neil was a wonderful human.

Gregg Bissonette (Ringo Starr & His All-Starr Band)

I did not anticipate the depth with which the news of Neil Peart's passing would affect me so profoundly. I met Neil in 1985, when the Steve Morse Band was invited to tour with Rush during the band's Power Windows tour.

Throughout my life, I have met quite a few incredibly talented individuals. However, Neil-his musical prowess being a given-was of a different ilk; a breed of human being whose talents, skills, abilities, and passions spanned a vast and varied spectrum that at times, to me, appeared beyond comprehension. Drummer, lyricist, author, philosopher, bicyclist, motorcyclist, cross-country skier, sailor, mountain climber were all part of his mantra of living life to its fullest. To choose just one of these endeavors, Neil didn't just hop on his bicycle for a thirty-minute cardio workout; on the '85/'86 Power Windows tour, if the next gig was within 150 miles, he would wake up at the crack of dawn and ride his bicycle for upwards of eight hours. And on a three-week break in the tour, he flew halfway around the world to ride his bike through remote parts of China for three weeks, only to return home to create one of his first literary works, chronicling this lifechanging journey.

Neil Peart should be an inspiration to us all, constantly reminding us just how precious life is, and how limitless the number of incredible experiences and challenges await us if we so choose. To know him only as the drummer and lyricist of Rush-an amazing accomplishment in and of itself-is to barely scratch the surface of this brilliant, driven, curious, multifaceted, genuine man. I am forever thankful for having had the opportunity to know Neil and to be eternally inspired by his passion and zest for life.

Rod Morgenstein (Winger, Dixie Dregs)

I heard 2112 or All the World's a Stage at a friend's house, in his basement, and I was immediately drawn to his turntable. I remember sticking my head between the speakers and being transformed to this totally different place of drumming, of music-just a different musical landscape. At the time, I was playing in bands and taking drum lessons, and at the school that I was in they would put together different bands, and I was in a band with these teenage kids, playing Ventures and Beatles covers, nothing too challenging. But as I discovered different drumming and styles, I immediately adapted to that way. So when Neil entered my life, I started what I would call my drumming vocabulary. It expanded because of him. Things that I would call drum hooks...when Neil played "The Spirit of Radio," I remember listening to the beginning section and how he and Geddy entered the song, and thought it was the greatest thing I'd ever heard. This was drumming that I'd never heard before. And for me, on every Rush album he totally took it up again. Take a song like "Freewill" [from Permanent Waves]. Man, the drumming on that, it's just beautiful the way he approaches it. Each verse, each chorus, he totally mapped it out for the drummer listening. And then you take the next album, which was Moving Pictures, where he totally stepped it up again, and probably created air drumming on that record with "Tom Sawyer." When that fill comes, it's like, What the hell? And he sticks in this cymbal crash in between the tom fill that was just totally unexpected. It's just beautiful. To this day I'm still inspired by Neil, by Rush. His passing hit me the hardest. He is, to me, the greatest.

Charlie Benante (Anthrax)

In 1993 Neil Peart called me to play on Burning for Buddy, an album and video project he produced that was a tribute to Buddy Rich. We had both played with the Buddy Rich Big Band in 1991 at a concert in New York City. It is well documented how Neil decided to follow that up with a larger project based on Buddy Rich's legacy.

During the Burning for Buddy sessions Neil approached me and very politely asked me what I had done to improve my drumming so much since we first met in 1985, when we both played on bassist Jeff Berlin's first solo album, Champion. I replied, "I've been studying with Freddie Gruber," who I considered my drum guru. Neil immediately wanted to meet Freddie. Shortly after, I introduced them to each other, and they hit it off famously. Neil took his lessons with Freddie very seriously, and he and Freddie became fast friends.

I saw Rush live a number of times and was always blown away by the band, the music, the presentation, and Neil's creative and compositional drumming. When Neil retired from touring in 2015, I was moved to tears when I read his Modern Drummer interview and how drumming had taken such a toll on his body. I'm sure it had to have been difficult to make that decision-to walk away when he did.

I knew Neil as a man of great humility, intelligence, and humor. His drumming has inspired generations and I'm sure will continue to inspire and inform drummers of the future. I am grateful to have known Neil Peart. He is already missed.

Steve Smith (Journey, Vital Information)

I sadly never got to meet Neil. In the late '80s, early '90s Neil would fly out Freddie Gruber from California to New York City and pay him crazy money to spend a week with him to work on drum things. During a few of those one-week visits Freddie would call me and ask if I was playing in town because he wanted to bring Neil down. The timing never worked. Sadly, I was either on the road or not working in New York that week.

Freddie and Neil loved each other. He would always talk about how much Neil loved jazz. That wasn't hard to believe, because while Neil played mostly rock language, it was obvious that he thought like a jazz musician, because he spent so much time going beyond just playing a beat with typical fills. Neil was always taking every section of a tune and arranging the concept and musical decisions and choosing atypical grooves and fills for the constantly moving and changing sections of Rush's music. I know from talking to many of Neil's friends, like Freddie, Terry Bozzio, Don Lombardi, and others, that he was, with all his success and status, a completely humble and sweet guy who loved everybody and had so much respect and love for music and musicians of every style. I will always wish that the timing had worked out, because I am sure it would have been a time I would have always remembered.

Much love, Neil.

Gerry Gibbs

I bought Moving Pictures in 1980, after hearing "Limelight" on the radio. Neil's entrance to this song alone was worth the price of the record. The songs were like no other rock songs that I'd heard. The clean, fat sound of the recording was as appealing as the songs themselves. And Neil's playing was infused with an intoxicating combination of sophistication, impeccable execution, and a decidedly rockin' feel. Neil Peart and Rush changed rock music forever. No band that I know of, before or since, has created such sophisticated and literary yet visceral and anthemic rock music.

Dave DiCenso (independent, Josh Groban)

Neil Peart was to my generation what Ringo Starr was to the previous one. He influenced countless people to play the drums, setting the bar incredibly high. Many of us would race home from school to learn his parts and play along with Rush records.

In addition to the incredible drumming and lyrics, I've always had great admiration and respect for his quest to improve. When Neil began studying with Freddie Gruber in the early to mid '90s, he'd already been inducted to the Modern Drummer Hall of Fame and would easily go down as one of the greats, even if he never touched a stick again. He later took lessons with Peter Erskine. As an educator, what a wonderful thing for me to present this to students as inspiration. Never stop growing.

Much has been made about his privacy over the years. I never considered that as something negative. I feel it helped to provide much introspection and contemplation that led to his fantastic lyrics. He also expressed himself vehemently in his books.

I had the opportunity to sit behind his kit during the Snakes and Arrows tour. A buddy of mine was good friends with Rush's monitor engineer, and we were there for soundcheck, etc. There's a scene in the movie Field of Dreams where James Earl Jones has the opportunity to go into the field where all of the baseball players came from. He first approaches the field with giddy hesitancy because it's a sacred place. That's how I felt when climbing into Neil's space. I never felt that way sitting behind anyone else's drumset. There was mystery, greatness, history-just like him.

Resilient. Craftsman. Renaissance man. Macallan. Author. Father. These are some of the ways I will remember him. RIP, Professor.

Jeremy Hummel (Into the Spin, DrumTip)

Neil Peart's passing creates a vacuum in the drumming community. We have lost one of the greatest minds of our instrument; a genius that inspired so many to go forward, to push the limits of one's creativity, to not settle for average.

I can safely say that if it weren't for Neil, I would not have even begun to play drums. He was my very first inspiration, the type of inspiration that makes a fifteen-year-old kid in Brazil who just listened to Moving Pictures for the very first time go crazy imagining what can be done on this incredible instrument we are lucky to play. So many musicians nowadays have him to thank for.

Neil also gifted us with a different, fascinating side of his personality when writing lyrics for Rush, and in his books, where we get a view into his motorcycle adventures. If that weren't enough, one can also draw endless inspiration from his resilient personality while going through some of life's most traumatic moments, such as the loss of a wife and daughter.

I perfectly remember being in the first row at Maracanã Stadium in Rio de Janeiro, watching their Rush in Rio performance in the early 2000s. That moment marked me forever, and I never looked back. A few years later, I made a move to the U.S. to pursue music full time, a lot of it fueled by Neil and how humble and hardworking he was. Thank you, Neil, for all that you did. Heaven is much richer now. Rest in peace.

Bruno Esrubilsky (Mitski, independent)

Like so many other preteen, misfit drummers "living on the fringes of the city" during the 1970s and '80s, I idolized Neil Peart. Every other kid like me felt the same way, and we constantly compared notes: "Can you play 'Tom Sawyer' yet?"..."Which is your favorite Neil solo, 'Working Man' or 'YYZ'?"...etc.

But he meant so much more than that in retrospect. Our fascination with Rush music and Neil's unique drumming kept us out of trouble and focused on emulating him in every way, trying to nail his fills, and even analyzing his lyrics. He brought so much joy, diligence, ambition, motivation, and musical/rhythmic curiosity to young, aspiring drummers. When I think about it now, copying his parts perfectly was never the most important, impossible goal that I made it out to be then. The process of trying sparked my own ideas and was of even greater value. I became my own drummer while trying to become him!

I know I'm not alone with that sentiment, and that's a beautiful legacy. Rest in peace, Master Neil.

Bob D'Amico (Sebadoh, the Fiery Furnaces)

What can I say about Neil Peart's drumming that hasn't been said yet? A groundbreaking, massively influential, outstanding, virtuosic, contemporary, inspirational prog-rock master at the top of his work! No question, and maximum respect for that-but to me personally he was much more than that. Any time I've listened to his interviews, that incredibly intelligent, reserved appearance, the choice of words, the kindness, modesty, message, humorous storytelling, and kind personality mesmerized me. He made me feel proud to be a drummer! Through my super-intelligent late father-who was a lawyer-I've always been a great fan of literature, and Neil, as the lyricist of Rush, has truly been the master of words as well as the drums-my two favorite things on planet Earth!

The other thing that greatly resonated with me over twenty years ago was the fact that someone of his caliber, career, fame, fortune, and reputation started taking drum lessons from drum guru Freddie Gruber in L.A. This kind of respect, "eagerness to learn" attitude, hunger for knowledge, modesty, and dedication to the art form of drumming is something that'll forever inspire me, and I believe this is truly something we can all learn from. This inspiration to me personally means much more than trying to learn or copy his drum beats, licks, and grooves. Thank you, Professor. May you rest in peace.

Gabor "Gabs" Dornyei (independent)

Shortly after I began my association with DW (which lasted from 2006 to 2015), Don Lombardi-the founder of DW as well as the Drum Channel-put me in touch with Neil Peart. Neil, who had been studying with Freddie Gruber, was looking for a jazz drumming mentor who could help him with some specific things related to an upcoming Buddy Rich Memorial Concert performance (which took place in 2008). Neil was not the first rock drummer to come knocking on my door by way of Oxnard (the home of DW), but he was certainly the most serious as well as the most famous. He was ready to get to work.

I treated Neil in pretty much the same way I would treat any student, allowing for his schedule to determine the frequency of our get-togethers but not allowing anything about his fame to get in the way of his learning. And he brought only humility plus keen attention to our first and every subsequent lesson. He wanted me to show him some things and I happily obliged.

Neil was very self-aware and knew that the relatively limited instruction he received during his formative years (limited in the sense that he began working well before he'd had an opportunity to do something like study at a conservatory...then again, how many rock drummers study at a conservatory? Quiet down and that will be enough from you for now, Mr. Aronoff ) did not provide him with the same set of tools that his drumming heroes Gene Krupa and Buddy Rich enjoyed. As I understood it, Neil was self-taught for the most part, and he did not spend much time in the jazz universe.

Neil's homework consisted primarily of listening to recordings I had chosen for him and then practicing the hi-hat. As he was getting ready to go out on tour with Rush, I asked him what his backstage warm-up set consisted of: Was it an entire drumset? ("Yes.") A big drumset? ("Yes.") "Well," I said, "your crew's gonna love me...I'm suggesting that you get rid of all of that and just have a drum throne and a hi-hat so you can really focus on this. Okay, a practice pad, too." I'm not sure that he followed my advice on that, but he did spend a lot of time working on his hi-hat technique...not for anything fancy, just to get better-acquainted with the art and feel of opening the hat a bit just before the swung 8th note would be played. His years of not playing jazz pretty much solidified his habit of opening up the hat for beats 1 and 3, a kind of binary rock thing, I guess. To be honest, I am not certain that Neil ever fully "got" the jazz hi-hat thing. What he got, I hope, was the confidence to go out there and have fun playing it. Note: the trial by fire of playing a Buddy Rich chart can be anything but fun. Now, maybe I'm a lousy teacher. But I do know that these lessons (which touched on things other than/in addition to the hi-hat) did manage to open him up to being more in the moment with his drumming. He told me so, and I believe him.

We wrote to each other in bursts of inspired communication, always followed by silence. I so enjoyed our correspondence. I don't want to betray anything that he confided or wrote to me, but the following will reflect the genial tone of our missives to one another:

November 5, 2009, 3:43 A.M.

Hello Peter,

I hope all's well with you and Mutsy.

I have just posted a new story on neilpeart.net with some thoughts on drumming I hope you might appreciate.

Hope to see you sometime soon!

NEP

The link to the piece is not active now, but I recall that he recounted our lessons in some detail and was very generous with his kind mention and praise of me. It was titled "Autumn Serenade."

I replied:

You're a good man, Neil.

Thank you for that Autumn Serenade.

(in return, a haiku for you, being sent from the delightful city of Helsinki)

Went for a walk here.

The calendar says Autumn.

My ears say "Winter."

Peter

Much has and will be written about Neil. Many drummers will talk about the influence he had upon their drumming. Neil had a very big influence on me, but it was not so much related to my drumming. It was more of a life thing. I'm improvising here, kindly bear with me....

Neil enjoyed great fame and adulation. He worked tremendously hard to achieve all of that. Neil reveled in the work process and did not take a moment of it for granted. How many of us can play an extended solo piece-in the midst of a mind-bendingly complex series of songs where intricacies abound, most of them at full throttle-and not only hold the attention of a stadium full of people but thrill them as well? I know that I can't. Yet, he filled his days with the reading of books and devouring thousands of miles on the open road with his motorcycle. I guess that, in the process of testing himself, he wanted to learn how much a man can explore and endure. He experienced and he lived life, and he knew that the only meaningful way to do that was to do it. To put in the work. To set out.

And, thanks to meeting him, he indirectly encouraged me to emulate his fearlessness of experience. For me, it was with a word processor and a camera, not a hi-hat or a Harley-Davidson. He encouraged me to express myself on the page. I'm enjoying the journey. I wrote a book (No Beethoven), and he penned a gracious quote for the back of the book. Thanks for that and more, Neil.

As you might imagine, I think of him often. His death came far too soon. His work and his inspiration will live on.

Peter Erskine

As an exponent of reggae music, I have always been paying close attention to the pioneers of the genre. However, after in-depth research, Neil Peart made me realize that I had to think out of the box, and that there is much more to learn. His approach was not just a mere, "set up, play for a few hours, get paid, leave, and repeat the routine tomorrow." No! It was in fact a lifestyle for him.

Neil viewed the drums as much more than an instrument. He had a dream kit, a setup that blew everyone's mind. That's where I'd say the term "office" was derived. His methodology of drumming was conversational rather than a monologue. He engaged his audience and gave them an experience. By himself he was a complete band; however, this does not take away from the fact that he complements the band immaculately and his fellow musicians are just as present. He took the risk of reinventing himself after thirty years, when many would have gotten complacent. It was an indication that no matter your level, you should never stop learning, and that there are endless opportunities to become a better you.

Certainly he has impacted the lives of drummers with confidence around the kit. Additionally as drummers we are not shadows; we represent the backbone. Another lesson is that there is an area for all, from the simplest of drummers to the "beasts."

Neil, I will continue to engage my audience and value them for turning up for the experience. I will not be confined by the rules but rather think out of the proverbial box. I will continue to reinvent myself. Thanks for sharing your gift with the world. You have certainly left an indelible mark.

Courtney "Bam" Diedrick (Damian Marley, Playing for Change, I-Taweh)

Just the fact that Neil Peart appeared on more covers of Modern Drummer than any other drummer shows his importance in the drumming community. I have never seen such commotion in the media and on social media-all musicians and bands, without exception, were in shock with his sudden departure. He definitely set a new standard of excellence for decades to come, and all drummers, no matter what their style, respect everything he has done for our class. He will always be a unanimous favorite among us.

His work continually evolved over each of Rush's albums and has influenced at least four generations-and he will undoubtedly continue to be admired. What always caught my attention was his construction of groove patterns. Each time he repeated a part, he would add a new layer, progressing the original idea with an added variation-this was a very strong and clear element of his style.

Countless times, he reinvented himself with new musical concepts, too. Right in the middle of a successful career, he returned to study with Freddie Gruber. This showed that everyone, even the greats, can continue to study and learn new things-a lesson in humility from one who never left the top.

All virtuous drummers, at some point in their careers, were influenced by Neil Peart. My own groove construction was based on Neil Peart's style. The best example of that is my "PsychOctopus" drum solo. Immortalized on the 2011 Modern Drummer Festival DVD, it was totally inspired by Neil's solo "The Rhythm Method," from the album A Show of Hands. I have always made a point of making this clear to everyone who listened, and if this solo becomes a classic within my own repertoire, I am forever grateful to the peerless Neil Peart for the inspiration.

Aquiles Priester (Tony MacAlpine, W.A.S.P.)

Though I'd heard Rush on my local rock stations, I became convinced of the band's brilliance after the release of their Permanent Waves album. I couldn't put this record to the side, captivated from beginning to end by the production, mix, songs, solos, individual parts, and especially the drums. The release of their follow-up record, Moving Pictures, solidified the band's stamp on my musical consciousness and vocabulary. Only in my early teens at this time, I'd question myself in my approach to all things drumming based on Neil Peart's recordings and interviews.

I had always wondered how Neil got that hi-hat tone, crispness, and explosiveness. Well, in a Modern Drummer interview in the early '80s he mentioned what he used: a 13" Zildjiian Quick Beat top and a 13" New Beat bottom. I got that combo the first chance I got.

He mentioned his stick choice in an interview as well, Promark 747s. The same pair of sticks my father put in my hands when I began drumming. I silently felt proud that Neil preferred this stick, too. I would also later have a similar feeling about us both being DW artists.

Other things that drew me into his playing: His ride work. That playing up on the bell reminded me of the patterns Lloyd Knibb would play with the Skatalites, but applying it to some banging out and sophisticated rock music. And it was clean, articulate, and purposefully placed, like everything else he did.

He'd squeeze in full-on jazz chops in a way that was unlike anyone else at the time. He also sent me on a mission with classical/drum corps style snare work that was well constructed and executed.

Some of the funkiest drummers I know went in on "Tom Sawyer" because the groove was undeniable. "YYZ" was on everybody's list, too. His fills were so tasty that everybody had to learn them all, along with their sequence.

The way he'd play odd time signatures gave me grief, but he made them feel as normal as 4/4.

The fact that he also played the marimba, bells, and other percussion but also wrote mind-expanding lyrics blew my mind.

My brother Norwood Fisher (bassist), Kendall Jones (original guitar player for Fishbone), and I even started our own progressive-rock band. We were super influenced by Rush, and I got to try all of that "what would Neil do?" stuff. Those four-stroke rolls are still one of my go-to licks, among other great things I got from listening so attentively to the work of the great Neil Peart.

Highlight: Standing behind him off stage but with a clear view at a festival in Canada. Educational to say the least. Truly,

Phillip Fisher (Fishbone)

In 1986, someone played me Neil Peart's legendary drum solo on Exit...Stage Left. I was instantly captivated by the energy, musicality, sound, and technique I heard in that solo, and it helped set me on my lifelong drumming journey. I spent much of my time from the age of twelve to seventeen listening to Rush and learning to play Neil's drum parts. This turned out to be a fruitful course of study, helping me in particular to develop a strong sense of four-limb independence, which continues to serve me well as a jazz drummer.

I saw Rush live thirty-three times between 1987 and their final tour in 2015. In concert, Neil had a nearly unparalleled ability to not only play all of his carefully composed parts accurately, but with incredible clarity and projection-every note was crystal clear, even at the back of a giant arena.

I continue to listen to Rush regularly to this day, and I'm always discovering new things in their music. Although I make my living playing music quite different from Rush's, Neil Peart remains my biggest influence and favorite drummer-my number one. Thank you, Neil.

Paul Wells (Curtis Stigers, Vince Giordano)

I've long thought that Neil Peart was the Escoffier of the drums. One of the most famous chefs of all time, Auguste Escoffier's approach to French haute cuisine was shaped by his time spent in the military. In Escoffier's "brigade de cuisine" approach, every member of the kitchen staff had a highly curated role and was expected to execute their contribution to each dish with militaristic precision. As a result, when we dine at a high-caliber restaurant in 2020, dishes arrive with consistency and precision, crafted thoughtfully, executed with impeccably high standards.

So too with Neil's drumming. Those larger-than-life, highly air-drummable fills at the end of the guitar solo of "Tom Sawyer"? He played them in London in 1983 exactly the same way that he played them in Concord, New Hampshire, in 1990. That syncopated 16th-note ride cymbal pattern in "Red Barchetta"? Same in Flagstaff, Arizona, in 1987 as in Brazil in 2002. The intro fill in "Limelight" after Alex Lifeson's opening guitar arpeggio? Same in...okay, you get the point.

Consistency. Intentionality. Night. After. Night. Sticking the landings. Landing the stickings. Serving the audience with the highest of quality. The deliberate similitude in Neil's execution was a feature, not a bug. Thank you, Neil.

Mark Stepro (Butch Walker, Brett Dennen)

Neil showed us how to make the drums work on every level. His tweaking of sounds, toms, and combining the pads with the drumheads and forming a unique style-he kept always changing with time and being the best drummer he could be at each moment. Today we study his recordings, we watch his videos, and we still learn with every lesson he left behind. To that you add his skills as a writer, and you get a master at his craft. We drummers now are left with this huge library of ideas, styles, and motivation from one of the greats.

Frank Amente (iLe, Baterisma, Calle 13)

Neil compared the physicality of drumming to that of an athlete. I think the best athletes are students of the game-constantly observing details and subtleties in order to continue to grow, excel, and stand above the rest. As a drummer and former athlete, I consider Neil a superior student of the game. He pulled inspiration from those musicians he admired and took ideas and execution to levels most of us only dream of achieving. Supremely technical, musical, and creative, his mark on the community is immeasurable.

Dena Tauriello (independent, Broadway's Little Shop of Horrors)

Never have I been aware of someone with such a dedication to their craft that, even in his forties, while already considered by many for decades to be one of the absolute best to ever pick up two sticks, he took drum lessons again to expand that craft. For me, that's huge. Not as huge, though, as hearing "Tom Sawyer" on the radio for the first time at age seven and being drawn into the world of Rush and, as a drummer, Neil Peart in particular. I would have to count him more as an inspiration than an influence, because his level was so far beyond anything I have thus far been able to approach. But many, many hours of my life have been spent trying to learn his licks and fills. Every once in a while, someone comes along who changes the game completely, and Neil Peart was one of the few that unquestionably changed the way the instrument that we all love was perceived and approached going forward. Rest in power, Professor!

Kliph Scurlock (Gruff Rhys)

As a young drummer I was in awe of Neil Peart's technical prowess and the amount of drums he played-wow! But what resonates most with me is that he was not just the drummer for Rush; he wrote the lyrics and was the driving force of the band. And from what I've heard, he was also an extremely kind person. He elevated drummers as people and demonstrated that they do more than just play amazing fills. They are also intellectual, and he made that cool. What an inspiration for other drummers and musicians. He strived to always be the best he could possibly be and was constantly learning more about drumming.

Kevin March (Guided by Voices)

There's something about Rush that drummers tend to gravitate towards. For me it was a way to test and expand my own skills against one of the greats. At some point my taste in music changed considerably, but I was always drawn back to listen to Neil's remarkable drumming. Precise, well-considered, and executed with ferocious intensity, which is clearly a mirror of the kind of person he was. Thank you, Neil.

Ira Elliot (Nada Surf)

Neil Peart was a force on the drumkit. As a kid growing up in Baltimore, Rush was played faithfully on the local hard-rock radio station. How did he play like that? I still don't know the answer, but it certainly sounds cool.

Tim Kuhl (solo artist, Margaret Glaspy)

Ritualistically playing through Moving Pictures as an eleven-year-old boy introduced me to the musical excitement I'd chase for the rest of my life. Neil invented me. Hitting the last third of "Red Barchetta," feeling like I was in a speeding car, seeing the landscape rush by, it converted me-made me want to be a musician. Thanks, Neil! Much love to you on your way.

Matt Johnson (Jade Bird, St. Vincent, Rufus Wainwright)

Neil Peart was such a monumental figure. His knowledge of the instrument was invaluable, and his willingness to share spoke greatly of the kind of individual he was. He will live forever through his musical contributions.

Chaun Horton (Alice Smith/Nate Mercereau)

I grew up playing jazz music around my grandfather. At the age of ten, I was introduced to Rush. Neil's drumming captivated me. I didn't realize it at the time, but Neil was the bridge for me between rock drumming and fusion/jazz, where drums are more deeply involved in the song presentation. Many aspects of Neil's playing permeated my musical development: his creation of "contra" melodic ride crown patterns made a second melody to the music; the use of orchestra and electronic tones added to the kit; and Neil's use of crashes in the middle of tom fills. He used these stabbing kick/cymbal punches in a new and deliberate way. After many years of playing, I can still hear where his influence shows up in a way that makes me think about the composition with more reverence. His poetic and lyrical mastery played a huge role in his drumming, connecting drumming with the composition, similar to how jazz drumming uses melody parts. I barely knew the lyrics to the songs I was playing with bands, while Neil was writing all of his!

I met Neil through Freddie Gruber. We were studying with him at the same time. He was a man of precision and diligence, in everything he did. Rush's shows were displays of how to give back to fans, always providing more than what was expected. I was at Neil's second-to-last show on the R40 tour in Irvine, California. It was the best concert I've ever seen and a fitting finale to an amazing career. Neil will rest alongside the greatest to play this instrument. His memory will live on for many reasons, none the least of which is best described as: Excellence. Bravo, Neil! Thank you. RIP.

Russ Miller (Andrea Bocelli, American Idol)

Tom Sawyer was just a book by Mark Twain until Neil Peart got ahold of it.

I was in college when Moving Pictures dropped, and after that, in a way, Rush was over for me. I so loved that album. They trimmed their excess, crafting some amazingly memorable songs complete with all the energy and element of surprise that made them Rush. I also distinctly remember the presence of the instruments on that LP. It introduced a new level of high-fidelity to our stereo systems and our ears. It was like being in the room with the band! For me it was their apex. I caught the Moving Pictures tour and was swept into the tribal joy of air-drumming along with Neil Peart in an arena full of the devoted. Big fun!

I think Neil was the harbinger of a new breed of rock drummers not directly influenced by jazz/swing-based music, as were the first generations of rock drummers from the 1950s and 1960s. Besides the jazz/rock fusion of Billy Cobham's work with the Mahavishnu Orchestra, which was undeniably influential in fueling Neil's imagination, jazz was not originally a component of his approach. But, from a different direction, his approach to drumming was as forward thinking as Max Roach's was-putting the drums out front and adding to the vocabulary of the multi-percussion kit. He was able, in the space of the trio setting Rush employed, to create compositional parts beyond beats and-like Elvin did improvisationally with Coltrane-made the drums an equal voice in the music. And, like Buddy Rich, Neil too greatly inspired generations of drummers with his mindful, whirlwind approach to drumming. I couldn't help but notice that Neil passed on January 10, the same day Max Roach was born in 1924. Coincidence? Each possessed formidable imagination, leaving an indelible mark on our instrument and music as a whole. Let's make it a celebration day.

David Stanoch (David Stanoch School of Drumming, Percussive Notes)

It's no secret that Neil Peart is one of the most influential drummers and lyricists of all time. You cannot listen to a Rush song and not break a sweat air-drumming to his perfectly calculated parts.

Neil made lead singers want to be drummers, made guitarists want to trade picks for sticks, and inspired everyone to learn his beats note for note. He elevated the game to make drummers strive to get better and be more creative behind the kit. He showed us all how to step outside the box and make the most complicated licks seem so musical and perfect-you can't imagine them played any other way.

We've lost a legend, an innovator, a hero, and an icon. His imagination and creativity brought out the drummer in all of us. Neil's musicianship will continue to inspire generations to come, and his legacy will be untouchable for the rest of time.

RIP Neal Peart

Tucker Rule (Thursday, Frank Iero and the Future Violents)

Air-drumming to "Subdivisions" as I type... the first time I read about Neil Peart was in an interview with hero Brad Wilk from the November 1996 issue of Modern Drummer-the year I started playing. Peart's drumming blew me away, with equal parts precision, power, fearlessness, and finesse, and it still had room to deliver joy. Thank you, King Neil. Your compositions, lyrics, discipline, and curiosity will forever inspire my drumming, writing, and productions.

Elliot Jacobson (Ingrid Michaelson, Elle King, sessions)

My drumming path was forever changed after hearing my first Rush song-"Tom Sawyer," naturally. That inherent eight-bar drum break is practically a right of passage for a drummer to learn. This was also probably the first time I ever tried to play an odd meter. I was hooked and went out and accrued every album (on cassette or vinyl) I could find. Moreover, my mind was blown when I found out that the drummer wrote all the lyrics. I remember going as far as to pick up a copy of Ayn Rand's The Fountainhead because Peart attributed some of his lyrical content to her philosophical ideas.