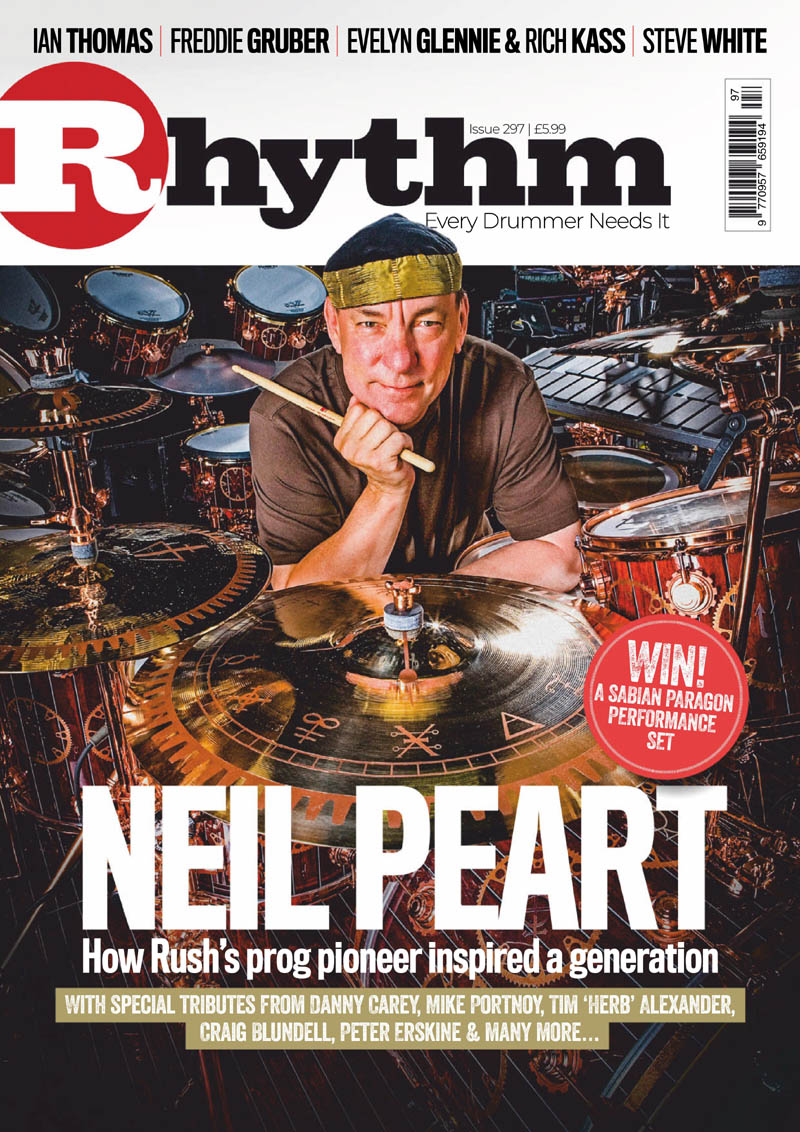

Neil Peart: The Measure of a Life

How Rush's prog pioneer inspired a generation

By Chuck Parker, Rhythm, November 2020, transcribed by John Patuto

An in-depth and moving tribute to The Professor, exploring his musical genius, his setups and sound, his intelligence, enthusiasm and artistry - with praise paid by a host of fellow artists and friends

We honour the memory of Neil Peart's incredible musical life, and the countless players he befriended and inspired, with an in-depth exploration of the man and the musician.

Most everyone will experience a game changing event in their life. That moment in time when you realise that nothing will be the same. This experience can occur through exposure to new knowledge or altered insight on differing opinions. In the case of musicians, this can be hearing instrumentation used in a different way or discovering a new artist for the first time.

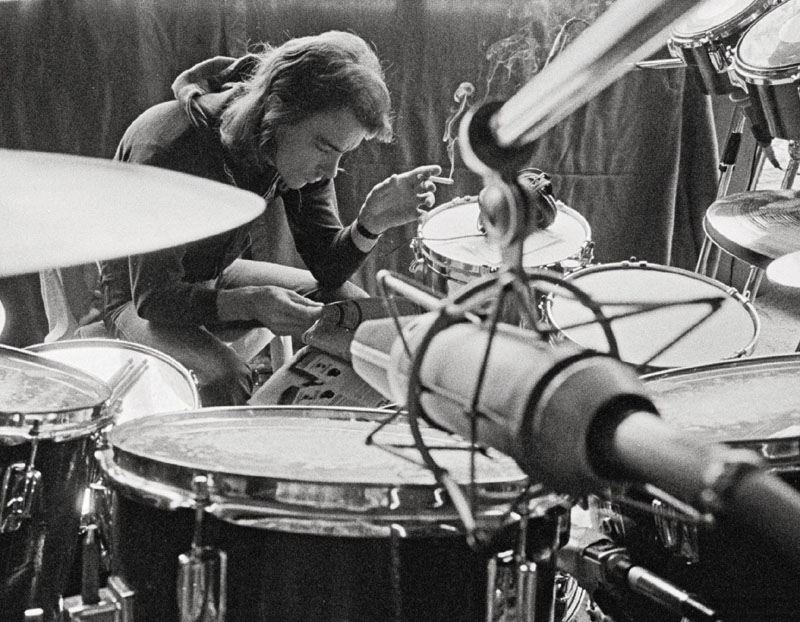

For millions of drummers, especially those that came of age in the '70s, one of those moments was when we first heard the band Rush and their drummer and lyricist Neil Peart. My moment occurred in the back seat of a friend's Datsun B210 in early January of 1977, right after Christmas break.

We gathered in the usual desolate corner of a cemetery for our morning ritual of listening to music, talking and having a smoke before school. My friend knew I had been gifted a drum set that holiday and, after passing me a smoke, handed me an 8-track tape, smiled and said, "Check THIS drummer out!"

Just one look at the photo on the front of the cartridge left me spellbound. It was Rush's first live album, All The World's A Stage. Peart's chrome Slingerland kit glistened under the spotlights like a jewel in a king's crown. I immediately had to hear what this band sounded like. "Play it!" I urged. The opening chords of 'Bastille Day' poured from the speakers, and as soon as the drums and bass kicked in, my body was covered in goosebumps. I knew, in that moment, my life was changed.

I'm sure I confused my school teachers in the months and years that followed as I suddenly became interested in the French Revolution, Ayn Rand, English literature and Shakespeare. This is the impact a "rock drummer" had on my humble 16-year-old life. I bought that double live LP the very next day. So began a love affair with a band and a drummer that continues to this day.

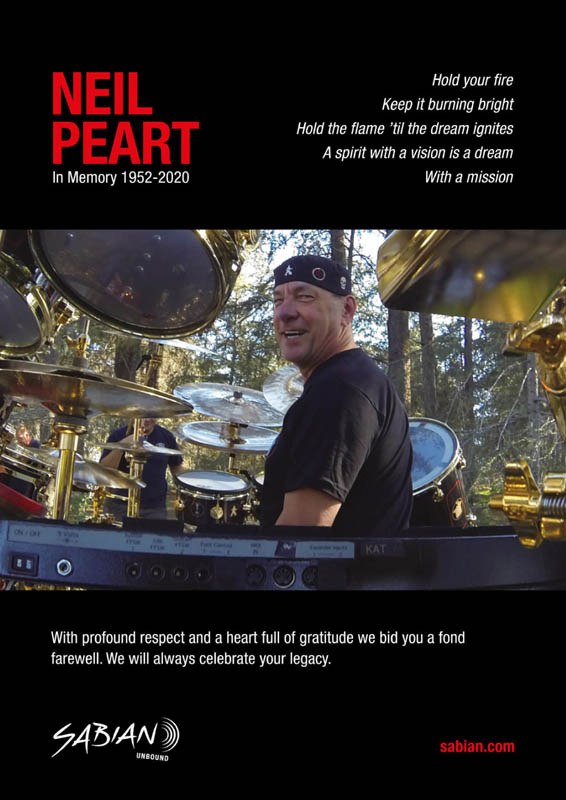

Just as I remember so sharply the first time I heard Rush, so too will I always remember the moment when I was informed of Peart's death. I was out hiking and snowshoeing (one of my favourite pastimes, partially inspired by "Pratt"). I received a text from a close friend that just said "RIP Neil".

Like so many others, I was unaware of his battle with glioblastoma (a form of brain cancer), and the news left me in complete shock. In yet another testimony of the admiration the man generated, all who knew of his condition had kept their silence for more than two years out of respect for his privacy.

Peart often wrote in his books about ending a long day during his travels on his motorbike with a smoke and a sip of The Macallan... In his honour, then, prepare your favourite libation, and join Rhythm as we take a very special look at one of, if not the, most influential rock drummers of the modern era...

A BRIEF HISTORY

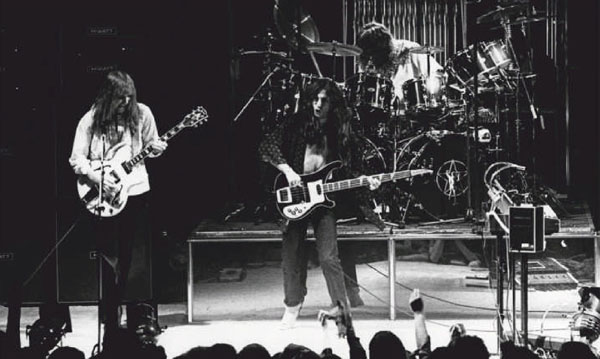

Not much more can be told about Peart and Rush's history that hasn't already been written, but for the uninitiated, the band entered the music scene storming out of Toronto, Canada during the late '60s with a direct rock-and-roll approach as a power trio. After getting noticed in the US, thanks to radio disc jockey Donna Halper, the band was on the verge of success when original drummer John Rutsey was advised not to tour due to health issues. Enter Neil Peart.

After a disappointing foray to London seeking his fame and fortune in the music industry, Peart returned home to St. Catharines, a suburb of Ontario, Canada. It was while working at his father's International Harvester tractor parts store and playing in local bands in the St. Catharines area, that he received the fateful call to audition for Rush.

Neil's addition not only elevated the band musically, but he became the principal lyricist simply by default. A lover of words and reading, Peart willfully accepted the challenge. Although modest in his own evaluation of his work, his lyrics grew and progressed just like his drumming. Always one to embrace music technology and innovation, Peart adapted that aesthetic to his lyrics as well, writing about topics far removed from the typical banality of top 40 pop radio.

Rush eventually conquered the charts, however, and achieved considerable success in singles and album sales. This culminated in their recent induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame after many years of eligibility. Usually one to shy away from public events or spotlights, Peart commented in his acceptance speech, "We've been saying a long time, years, that this wasn't a big deal. Turns out, it kind of is".

Indeed, it was a very big deal for the millions of Rush fans around the world who so loved to share the object of their obsession with others. Rush being "indicted" as Peart put it, was solely for the fans. Neil also quoted Bob Dylan by adding, "The highest purpose of art is to inspire... What else can you do for anyone but inspire them?" In my personal life experience, Neil Peart is the truest embodiment of this statement.

WORDSMITH

In addition to Peart's immeasurable impact in the music and drumming world, his other artistic contribution was his love of the written word. This was apparent through his command of language, whether writing or speaking about an idea, be it in a song, interview or book. Peart always seemed to use the perfect word or phrase to convey his thoughts.

Many music lovers had difficulty getting past bassist and singer Geddy Lee's unique vocals. To some, he was a wailing banshee while others thought his original sound fit Rush perfectly. But even those who couldn't get past Lee's singing had to admit the proficiency of Peart's prose.

Peart had a way of making the most complex topic simple and shined a light on simple things that turned out to be complex. I always think of the song 'The Trees' off the Hemispheres release. In prose that Peart himself has shrugged off as simplistic, the song tells a story of equal rights achieved by drastic measures, wrapped in a progressive musical package. It is just one example of Peart's command of lyrical metaphor and allegory.

In addition to his talent as lyricist for the band, Peart also wrote several books. Most relate to his experiences travelling, either while touring or on his own. Neil was famous for either motorcycling or bicycling between gigs while on tour. One of his most poignant books is Ghost Rider, which chronicles his experience of suffering not one, but two fatal tragedies. The first involving the death of his daughter in an automobile accident, and the second, the death of his wife barely a year later. Neil was famously private throughout his life, but if you wish to know him, you merely have to read his words.

INFLUENCES AND INSPIRATION

Listening to Peart's static fills, one can hear Keith Moon's influence. Never one to just play a roll and crash on the '1', Peart was constantly peppering his fills with off-beat accents and unusual sound source choices. Cowbells, China and splash cymbals, wood blocks and timbales were just a few of the colours that Peart chose to paint with from his palette. Just as Moonie's choppy, seemingly chaotic, fills worked for The Who, Peart's personal style meshed seamlessly with the musical direction the other members of Rush were headed.

Another percussionist in a power trio that preceded them and who Peart looked up to was Ginger Baker. Just as Baker brought his jazz sensibility to Cream's rock idiom, so Peart brought his progressive leanings to Rush, pushing them to another musical level.

On the other end of Neil's influences were more disciplined drummers that emerged from the British progressive rock scene: Carl Palmer (Emerson, Lake and Palmer), Bill Bruford (Yes, King Crimson) and Michael Giles (original King Crimson drummer) all had an effect on Peart. But the influences didn't stop in his formative years. Both Peart and Rush are famous for continuing to be influenced by other styles of music. A great example of this is Peart's respect for Stewart Copeland from The Police.

At a time when there was a lot of peer pressure in my personal music choices, Peart validated my opinion of Copeland and The Police by praising him publicly in interviews. Rush's Signals and Grace Under Pressure both showed The Police's influence on their music.

Another example was his fascination with Buddy Rich, big band and jazz music. As drummers, most of us have heard the name Buddy Rich and are familiar with the musical legacy that goes along with him. As I made my way along my own musical path, Rich and his playing were a constant reminder of how far you could take drumming - and how far I had to go. I understood why everyone praised Buddy; he set a level of musicianship and excellence that was inspiring and hard to surpass.

Just as Rich inspired generations before me, Rush became my inspiration and Neil became my 'Buddy' - an interesting anecdote because Peart himself fell under Buddy's spell. Peart never considered Rich a big influence on his playing until a chain of circumstances (as The Professor liked to say) changed all of that.

In 1992, Cathy Rich, Buddy's daughter, invited Neil to perform at the Buddy Rich Memorial Concert. Peart dove passionately into the deep end, researching and rehearsing Rich's material to perform with the big band during the concert. Growing up, I was constantly told that jazz drummers were the "best" drummers and could play anything. While there may be an element of truth to this opinion, it was inspiring to me that my favourite drummer, who was considered a "rock" musician, played masterfully with Rich's big band. In yet another example of his influence on me personally, Neil's participation in the event inspired me to dig deeper into drumming history, and in so doing I gained a deeper appreciation of Buddy Rich and those that came before him.

Peart's experience with the concert also led to his involvement with two Burning For Buddy album releases, featuring a who's who of the drumming world playing arrangements of a variety of songs as well as Rich's big band tunes.

It's impressive that Peart managed to take all of those influences and homogenise them into his own personal sound. Even when he was years past his impressionable influential stage, Peart was still soaking up knowledge like a sponge.

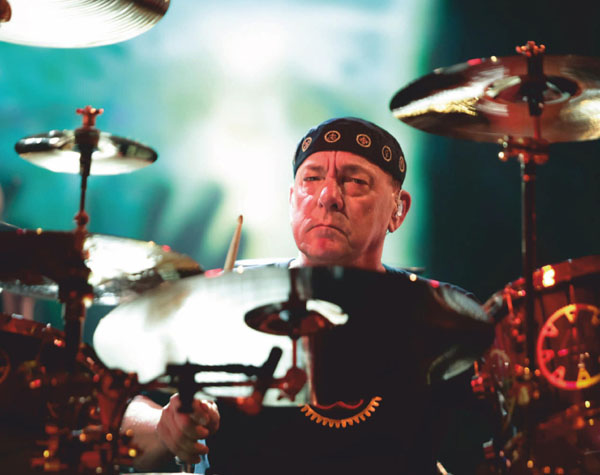

FROM ANALOG KID TO DIGITAL MAN

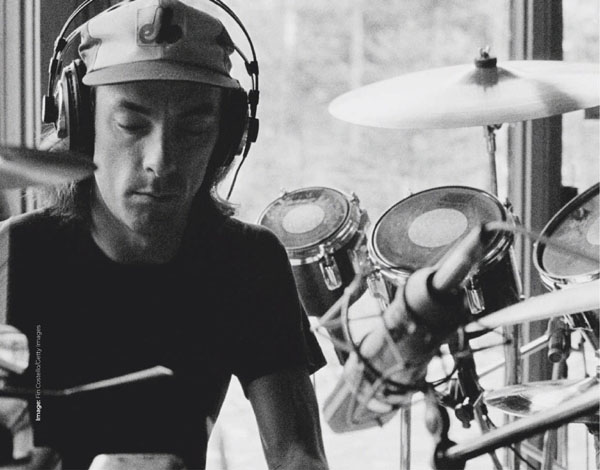

As a result of his experience with the Buddy Rich Memorial Concert and subsequent Burning For Buddy CDs, Peart reassessed his playing style and began to study with drum guru Freddie Gruber. After reaching the pinnacle of peer acceptance, winning awards and being voted top in many polls of various drumming and music magazines, Peart felt a need to reinvent himself. At a time when many would rest on their laurels, Peart was continuing to learn and challenge himself.

This process is wonderfully documented in the highly recommended video A Work In Progress. In it, Peart describes his journey of rediscovery as only he so eloquently can. In addition, he demonstrates the real-world application of his studies by showing how they applied to Rush's release at the time, Test For Echo. He altered his drum kit setup (always guaranteed to awe and inspire gear geeks) and went ergonomic like other Gruber disciples (Steve Smith, Dave Weckl and Peter Erskine).

Peart changed, but remained the same. 'Circumstances', anyone? He started to "dance" on the drums, as he often described Gruber's instruction. Peart's playing became more rounded and his groove even more pronounced. When I saw Rush and Peart on the Test for Echo tour, I marveled at the fluidity of his playing. It showed me that by selfishly pursuing his personal reinvention, the fans' reward was as satisfying to them as listeners as it was to Peart's sense of his own musicianship.

An excellent example of Neil's willingness to change was his relationship with electronic drums, triggers and samples. Originally a sceptic and not entirely trusting of the new technology, Peart changed his opinion. Throughout the '80s he experimented with electronics that included a secondary kit behind his main acoustic one, blending both worlds.

Peart's massive acoustic kit had inspired countless drummers throughout his career; now he was consolidating, morphing and making the most efficient use of the technology he had at his disposal. Peart was able to pack most of his percussion into his electronic setup by sampling his personal instruments and using the sounds with his Simmons pads throughout the '80s, and then with his Roland electronic kit during their later live years. True, in later years they used some sequences live, but always tastefully and musically.

Another testimony to Peart's precision was his ability to play with those sequences or a click live, yet push and pull the band to keep the live feel. While always serious and precise, Peart's playing never sounded mechanical or cold. There was always a human touch.

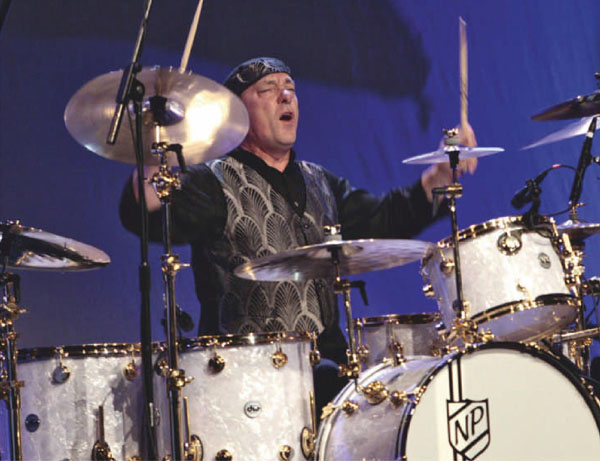

Peart's precision was his ability to play with those sequences or a click live, yet push and pull the band to keep the live feel. While always serious and precise, Peart's playing never sounded mechanical or cold. There was always a human touch.His physicality was also very apparent in his visual style of playing. Musically progressive, yet unflinchingly aggressive. Stick spinning and twirling didn't overshadow the fact that every note had a purpose. When Rush came roaring back from their hiatus with Vapor Trails, Peart once again caught our ear with his blazing double bass intro with trademark two surface ride pattern on 'One Little Victory'. It was unusual, as Peart never used his twin kicks for rhythms, only fills, and yet was one more example of Neil exploring his own style and willingness to do something different and outside the box.

THE LIVE ELEMENT

If you have ever experienced Rush and Peart live, you know you could always expect them to play their material exactly like the record. However, there were times where they would deviate from the script. They were famous for their instrumentals, medleys and the centrepiece: Peart's drum solo. If you did not get the opportunity to see Rush live, fret not. There is a wealth of live recordings that chronicle every phase of Rush and Peart's live evolution.

Neil elevated the drum solo from a mere display of chops to an orchestrated presentation, documented over the course of their live releases. His personal approach to soloing is captured in the Taking Center Stage video. In it, Peart again succinctly vocalises his thoughts towards his drum solos - another highly recommended treasure that gives insight into Neil's original approach to his craft.

In the March 2014 issue of Rhythm, Peart wrote on soloing, "I believe most humans can be stirred to their cores by rhythmic drum patterns - it is surely the oldest music. If a drummer can combine that primal instinct with structure, conversation, invention and a touch of theatre, the audience will be reached, even moved".

With a catalogue as vast as theirs, Peart often remarked on how difficult it was creating set lists for live shows. One creative way of squeezing in a little more material into a show was mashing up songs. Their creative technique of doing this can be found throughout Rush's live history, going all the way back to their first live album All The World's A Stage, with their combining of 'Fly By Night' and 'In The Mood'.

When I saw them on the Presto tour, they segued out of 'Freewill' into 'Distant Early Warning' with seamless precision. Later, on the Counterparts tour, they surprised everyone when they went from a blazing performance of 'Xanadu' into the fan-favourite instrumental 'Cygnus X-1 Book II: Hemispheres Part I: Prelude'. This was the kind of band Rush was, always eager to please fans by playing as much material as possible, but still satisfying their own creative urges.

Rush and Peart set a standard for their album-like perfection in concert in an era when bands were notorious for going all out in the studio, then having problems replicating it live. After listening to Rush's first live album for so long, my young ears were surprised when I dug back into their catalogue and heard studio versions of the songs that I had grown so familiar with from that first live album. It was truly ear opening to hear how Rush changed the arrangements slightly on some song kept others exact and left room in others for improv and risk taking. Here were three men pushing their studio capability to the limits yet still pulling it off live.

Rush and Peart's ability to morph and change yet still remain the same is a definitive example of a "progressive" band. They always used technology to their advantage. They had no shortcomings musically, so they didn't need to hide behind it. Every note laid down in the studio was replicated live.

Rush toured relentlessly, playing anywhere and everywhere with anybody and everybody. One of the more unusual times I saw Rush live was on their Farewell To Kings tour. They had not yet reached headline status and were opening for American rocker Bob Seger and The Silver Bullet Band. Most of the attendees were there for Seger, but by the end of Rush's energetic 45-minute set, the trio from Canada had won the crowd over.

Every time I saw Peart and Rush live, they played with that same passion. Rush was all about the music. No tales of debauchery or excess. No egos or infighting. The focus was entirely on the songs and the performance of them. They set a selfish artistic goal for themselves, which the fans benefited from.

Rush and Peart were known for their musical precision in concert. The closest thing to a mistake that I ever witnessed was on the Presto tour. They played 'The Pass', which has a very stark intro by Geddy Lee on bass with Peart echoing his riffs with a tribal tom-tom beat, and ethereal chiming guitar work from Alex Lifeson. Lee hit the note at the start of the song and the note was out of tune. Lee immediately looked to the side of the stage, stopped playing and ran behind the curtain to correct the problem. Peart continued playing, Lifeson continued chiming and Lee was back in on the beat within seconds with a properly tuned instrument.

Watching them react and seeing the smiles on all of their faces as they transitioned out of what could have been a train wreck, was an excellent glimpse into the looser live attitude they adopted during their latter career. Looser however does not mean sloppier. After so many years of being the staunch perfectionists that they were, Rush was finding room for fun. Their response to the above anecdote is but one small example of that. Other indicators were brilliant short films played before shows, after intermissions and sometimes after the concert had ended (available on the plethora of live videos the band has in their discography). Their involvement with several movies and television shows, most of a comedic nature, are all examples of Rush seemingly embracing the belief that sometimes life is too serious to be taken seriously. Being a staunch perfectionist all the time is exhausting, but Peart and Rush were finding room to relax.

FINAL THOUGHTS

I never had the opportunity to interview or meet Mr. Peart. As a music journalist, he was at the top of my short list as a feature subject, and I would have leapt at the chance to have had a conversation with the man. Sadly, that was not to be. However, I felt like I knew him through his music, lyrics and books. He wrote his heart on his sleeve, and if you want to know the man, all you have to do is enjoy the vast catalogue of material he has left behind.

If I had been given the gift of meeting him in person, I always fantasised about what I would say. I had decided on, "It's a pleasure to meet you, Mr. Peart. I really admire your work, and your drumming's not too shabby either". I have a feeling he would have appreciated that.

Thank you, Neil, for everything and know that your garden grows throughout the world and continues to be fruitful and bear inspired drummers and musicians in a plentiful harvest.

Peers on Peart

Tributes From Fellow Artists

TIM 'HERB' ALEXANDER

(Primus)

"I was walking to a friend's house in Riverview, Michigan when 'The Spirit of Radio' came on the boom box I was carrying. It shook my world. Complex but listenable. Powerful and interesting. It's got to be the best intro into a song, ever... It made me feel connected to something that couldn't be explained, and it became my focus to learn how to play like Neil. I would learn every note of every album until I started to become my own player and not imitate Neil so much - which was hard to do by the way! He was a major influence on me.

"As a kid I couldn't describe what it was that had such a big impact - it just was! The thing that made the biggest impression on me was how Neil would have different parts within a song; it wasn't just a beat that continued throughout. He would make changes from verses to chorus and create introductions to songs - even 'Tom Sawyer', where the main groove during the verses has a part that is evolving as the verse moves on. And his solos were unique, because they were a song in themselves - and he kept those themes throughout his career as if it was an ongoing composition. His composition really affected how I think musically as a drummer, and I always try to have that approach in my playing.

"My favourite memories of Neil are watching him play every night on tour when we opened for them, especially when he would come to my dressing room to hang out and jam on my practice kit, or bang on an ice chest - whatever was there... Man, I'm still so sad."

RYAN VAN POEDEROOYEN

(Devin Townsend Band/Imonolith)

"I was 14 years old when a buddy introduced me to Rush, and I remember hearing 'YYZ' and thinking, 'What the hell? This s incredible - listen to the drumming!' Neil was pushing boundaries, doing something completely different, and he made me feel that there was a ole new level to drumming. he biggest impact he had on me was how musical his playing was. He wasn't just keeping the beat and pulling off crazy drum fills; he thought out his cymbal parts to match the notes, or tones, of the music. It's why I have so many cymbals, and when people compliment me on my cymbal work, the reason is Neil Peart - you hear him come out in my playing. It's fine to borrow from your influences, but don't try to be them. They will always be the best versions of themselves. Be a first-rate version of yourself, not a second-rate version of someone else.

"Whenever Neil placed a fill, even in Rush's most progressive songs, it was perfect; and whether it was simple, or difficult, he was playing for the song. I have so many Rush tracks that are favourites for different reasons, but I always come back to 'YYZ'. You have your crazy fills and the 'proggy-ness', but there's this groove - almost like Neil's playing four on the floor. That song, encompasses everything that I think a drummer should know. It doesn't matter what you're going to be playing, you should have a knowledge of time signatures. Then there's the flashiness, the progressiveness, the drum fills, the cymbal work - that's all in there, too, and he's laying it down with that fat groove.

"I went to see Rush on their Roll The Bones tour. We hadn't bought tickets but we managed to get some and ended up in the front row! Rush came on, and I was just blown away. There were a few times where Neil and I made eye contact, and he gave me a nod. I remember walking away from that show feeling totally inspired. I'm doing what I do today because of it. The biggest thing was making that eye contact. There was an energy that was very influential."

JON THEODORE

(Queens Of The Stone Age)

"I can still remember being in the car on the way to school when 'Tom Sawyer' came on the radio. I was probably 10 years old, and I didn't know s**t, but when that monstrous groove came in over that deadly synth bass, it instantly resonated with me in a way I'd never known before. I knew in that moment that I was hearing something very special, and different, from all the other music I already knew. It was dangerous and heavy, like some kind of wild, sleek jungle cat on the prowl. By the time the 'A modern-day warrior' line hit, my mind was fully blown! It was one of those exhilarating moments when you experience a life-changing revelation.

"At that point, I wasn't even playing drums yet, but I knew that Neil was a different kind of drummer. I had already begun to focus on the drumming when I was listening to music - but when I listened to Rush, I couldn't stop the involuntary urge to air drum along with the beats and fills. Neil's playing was magic - compositional with the fearless creativity and thoughtful considerations of high art, but with the fierce heat and irreverent passion of rock 'n' roll. Such an elusive and rare blend.

"There are so many different Rush tracks that are essential for so many different reasons, but if had to pick one, it would be 'La Villa Strangiato'. It's long, with so many moves - the whisper to roar dynamics of the intro, the quintessential Peart ride cymbal beat, the odd time groovy space dub, the chunky tom hits, the spotlight solo, the 'Cab Calloway' demented disco tom groove and the rest of the inimitable aspects of his playing. It's perfect.

"Rush's final show at The Forum in LA was a night to remember. Literally everyone I know who plays drums in LA was there, and it was an evening of the highest revelry and praise for our hero, Neil, and his band. There were more toasts, high fives, belly laughs, huge smiles, synchronised unison air drumming and slack-jawed stares of disbelief than you could imagine! The band was inspired, and Neil put on a three-hour clinic for his adopted hometown crowd, who responded with roars of appreciation. His solo that night was unforgettable; it had all the depth, precision and calculated wisdom we've come to love and expect from The Professor, but it also flowed and blossomed with organic improvisations. There was a beautiful snare scene in the beginning that resonated like Buddy Rich or Tony Williams, where he'd change patterns and sticking to make the accents pop, or float - like the sound of a waterfall - that was so loose, free, inspired and musical that it took my breath away. From there, he took us on a journey through all the different aspects of his playing. It was a beautiful sight, and sound, and he was holding court and laying out for all to see the treasures collected from a lifetime of tireless crusading for inspiration and the relentless pushing of himself to evolve and keep learning. It was magnificent, and the fact that it was rumoured to be Rush's last show made it even more poignant.

"Having Neil acknowledge what I said about his playing that night is one of the proudest moments in my life, and to know that it meant something to him because I had 'got it' is something I will always treasure. As a fellow human and drummer dedicating my life to the pursuit of people 'getting it', I can't think of any more meaningful a validation than to have the blessing of The Professor. Forever one of my first and biggest inspirations, a trailblazing maverick who lit the path and showed us all what is up and how high the bar can be set. Long live Neil, and long live Rush."

MARCO MINNEMANN

"The first time I heard Rush was when I was about 16 years old, and a bandmate had the idea to cover 'Tom Sawyer'. I immediately thought it was very cool, and I transcribed the drum part. It made me instantly recognise how organised Neil's playing was. He had these great, very musical ideas; his drum parts were composed and his fills became trademarks It's mind blowing and beautiful to see so many people in the audience at a Rush show air drumming to his fills. You don't get that often, right?

"Neil was a very thoughtful writer and player, and both reflected his personality. I think what drummers can take from that is to be more of a composer on the drums than an improviser. Both sides have their values and places, but Neil showed the world that drum parts matter and can become a hook. And let's not forget about how great a lyricist he was.

"When I listened to Neil's playing, the discipline and obeying the grooves and structure in such a powerful way was something that definitely opened my eyes. When I met him, we discussed how both of us had moved to California at the same time from different countries. It was a very nice talk about life, friends and experience.

"For me, 'Tom Sawyer' still shows all the trademarks of Neil's playing: the force, the focus, the structure, the composition and the style."

CHERISSE OSEI

(Simple Minds)

"I first heard Rush when I was a teenager, and I remember being immediately excited and intrigued by what I was listening to - and thinking how appropriate their band name was. Their music definitely gave me an adrenaline rush and has done ever since! "I was fascinated by Peart's playing. I loved how complex it was, but at the same time so musical. I loved the parts he came up with - you could feel he was always pushing boundaries - and he made me want to explore more complex fills and work on my own technique and groove. He was one of the first drummers to play such difficult drum parts in mainstream rock music, and I also wanted to emulate his energy and precision.

"My favourite memory would have to be watching the live Exit... Stage Left DVD for the first time and being blown away by Peart's drumming. I was just mesmerised, and when the DVD finished, I felt so inspired that I went and played on my drums for four hours solid!

"For me, the must Rush track has to be 'Limelight'. It's a classic rock masterpiece, and I love the guitar riffs and the lyrics, which highlight Peart's feelings about being in the limelight and the difficulty he had with coming to grips with fame. I love the way Geddy Lee's voice sounds and the way Peart's powerful drumming drives the track forward."

CRAIG BLUNDELL

(Steven Wilson, Steve Hackett)

"I was a spotty kid in a record store when I first heard Neil play on 'The Spirit Of Radio', and I remember it like it was yesterday - the moment that Neil starts that ride pattern, just as it all kicks in... I have had many eureka moments in my life, but that was one of the most important. I didn't know what he was doing, but I loved it, and even though I didn't read music, I wore that tape out learning to play it, going backward and forwards trying to work out what the hell was going on! To this day, it's still my favourite sticking pattern, and it doesn't just belong in the prog genre. It's forward-thinking drumming at its very best and works across so many platforms.

"And that's the thing with Neil, he was such a pioneer in going forward... Everything was, and still is, ahead of its time, and it's stood the test of time. He was never content to sit still; he was always pushing forward to make the next thing better than the last, and that work ethic of not resting on your laurels has been a tremendous inspiration to me over the years.

"Neil chose when to blaze, but, equally, when he put less notes in it would be just as beautiful. He was the king of that, and it's an important lesson for young drummers who think they will find the answers in more notes. He always played for the song and was tremendously musical and intricate. There are few drummers who are instantly recognisable when you put on a record, but Neil is one of them, and I always go back to him when I need a burst of inspiration. For me, he is the epitome of musicality and determination.

"Sadly, I never did get to see Rush live, or meet Neil in person - two of my biggest regrets - but I am so proud to have played on the band's 40th anniversary album 2112 - 40th with Steven Wilson. We covered 'The Twilight Zone', and I was so nervous. We rearranged it completely, because I thought I would be assassinated if I tried to do the same as Neil! It's an experience that I will cherish forever, and simply to know that he listened to my drums puts a smile on my face."

RYAN BROWN

(Dweezil Zappa)

"The first time I heard Rush was on June 22, 1990 on the Presto tour, at Fiddler's Green Amphitheatre in Greenwood Village, Colorado. I was 14 years old, and it was a truly magical experience. I was mesmerised from the first note to the last, and I bought a T-shirt, poster and tour book! Everything about the show - the performances, the songs, the lights - it was the greatest thing I had ever seen or heard...

"It took me a while to figure it out, but the song that was stuck in my head for the walk home was 'Red Barchetta'. I was blown away by how creative and intricate Neil's parts were. His drumming was unlike anything I had heard, and Rush became the new benchmark for me. I thought if I could learn how to play along with those albums, I could probably play anything! It was like unlocking the ultimate challenge for our craft. I didn't realise at first that some of the songs were in odd time signatures, or that they were changing time signatures. I didn't know that was possible yet, I just learned the songs. Then, my drum teacher, Dave Robnett, taught me how to count them out. Looking back now, I feel like it was the perfect way to get into odd time music.

"Neil's influence made me want to make my drum parts more interesting, for myself and for the listener. I wanted to be as consistent as possible, and I wanted to hit hard!

"I was lucky enough to see Rush live 24 times, and while each show was absolutely incredible, there was something extra special about the show on the Snakes And Arrows tour on July 25, 2007 at Irvine Meadows, California. Neil, Alex and Geddy were all especially on fire that night, and I remember thinking during the show that it was the best performance I had ever witnessed. I tried extra hard just to soak it all up...

"For me, 'YYZ' has many of the classic Rush elements all in one song. There's the famous morse code intro. The main riff is in 5/4, but it changes time signatures and has the classic Neil ride cymbal groove along with trading bass and drum solos."

PETER ERSKINE

(Weather Report, Steps Ahead, Solo Artist)

"The first time I experienced Rush was after Neil had given me one of their CDs. Prior to our meeting, I had only heard about the band. As much as I tried to listen to everything when I was younger, my taste became more focused as I grew older. Needless to say, I was impressed.

"Neil put an extraordinary amount of thought and work into his drumming. The intricate complexities of that band's music, combined with his powerful execution of the drum parts, made as deep an impression upon the minds and spirits of music fans everywhere as Gene Krupa's drumming had done decades earlier. My takeaway was that Neil was the Krupa of our time. I can have great admiration for a set of skills without wanting to add those same skills to my toolbox. I'm not a stadium rocker and never will be. That said, Neil's drive to look fearlessly into an abyss will continue to be an inspiration. His curiosity and thirst for knowledge made him such a wonderful role model for all of us. The man had it all, but he continued to read and study. His was a life well lived. A good lesson for us all.

"My favourite memory is of seeing that smile of his in the missives he emailed to me. That, and the sheer pleasure that drumming brought him. He delighted in it, he celebrated it, he exuded and enthused it."

DANNY CAREY

(Tool)

"In 1976, I was well immersed into the rock world. I was literally earing out Yes, King Crimson, Genesis and ELP records monthly. It would take a lot for anything on the radio to spark my attention, so my snobby group of friends and I relied upon word of mouth from each other and der brothers to discover.

"I will never forget walking into my younger brother Dale's bedroom, where he was playing 2112. It made a really big impact from the first moment. There was great clarity in [Rush producer] Terry Brown's recording. All the 'proggy' elements that I loved were there, but it also had more of an aggressive quality to it. I really liked Geddy's voice also - it kind of scared me.

"Neil's drumming has always sounded very thought out and composed to me, which is rare in my world of rock. There is always a high level of articulation and sympathy to the other parts happening around him and excellent choices to help lead them through the journey. This is where his playing had its biggest impact on me. It was very good timing for me to hear Rush when I did, as I had just gotten my first Ludwig Stainless Steel Octa-Plus. At this stage of my playing, it was very inspiring to have this giant kit - but also somewhat intimidating.

"Listening to Neil's use of all the concert toms and percussion toys really helped me get a feel for how to use all of these new possibilities and apply them in a musical way. The thing I wanted to emulate most from Neil's playing, along with the aforementioned compositional choices, was his sound - specifically from the Moving Pictures album. The concert toms and kick sounds on that record are some of the best I've ever heard to this day.

"My favourite memory has to be the first time we met. It was about 10 or 15 years ago backstage at one of his shows in LA. They always say you never want to meet your heroes, so I was quite nervous about being there. Luckily, I had met Alex [Lifeson] before, and he introduced us. Neil's smile and hospitality were so welcoming, that all of my fears vanished instantly. The funny thing was, I don't think we talked about drums once. It was strictly about the important things like Scotch, BBQ sauce, motorcycles and family! I think that's the biggest reason we became friends.

"'Limelight' is a great example of playing the right thing at the right time and leading a song where it's supposed to go. A must for anyone who wants to learn from the best."

Essential Peart...

Mike Portnoy Shares His Highlights From Neil Peart's Drumming Legacy

When I discovered Neil Peart and Rush in the early '80s, it was very much a case of the right band and the right drummer at the right time. It was exactly the type of challenging music I was looking for to help me grow and develop as a musician in my mid-teens. Neil became my number one hero. Nobody was applying themselves to a big kit in the same way that he was, and I was fascinated by his setup, his incredible time signatures and the feel of his patterns. He constructed his drum parts in such a musical way, and everything he played was so meticulously thought out and crafted.

"I'll never forget my first Rush concert: December 1982 on the Signals tour. It was so surreal to be in the same building as those guys, and I have never felt such respect when it was time for the drum solo - everyone was air drumming!

"My first personal meeting with Neil came through Rhythm, and I still get a tremendously fond feeling when I think about that day. I got to be the fan boy - it was my job to ask him about drums! - but after that we struck up a great friendship that lasted until he passed. I have so many great memories, but one that's very poignant is from our last meeting on the band's final tour. Neil invited me down to the show and soundchecks as he always did - he was so welcoming and gracious - and I got to take my son, Max. Max played his kit at soundcheck, and it was very special to share that last Rush show with him.

"Neil was always so modest; he never acted like the drum hero and legend that he was. In fact, he always talked about how he could be better! From the golden era of Rush, here are my personal highlights from Neil's incredible drumming legacy, and it's these tracks and albums that helped make me the drummer I am today..."

Fly By Night (1975)

"The band's second album, but Neil's first with them. There is so much great drumming on here, but for me, the standout track is the epic 'By-Tor And The Snow Dog'. It's one of the first Rush songs that I learned to play, and the drumming is so challenging... I particularly love the middle section with the mini drum solos and the really cool, progressive pattern, where every bar takes away one beat. That creative, and very clever, nature of playing with numbers and patterns really appealed to me."

Caress Of Steel (1975)

"Probably one of the most underrated albums in their catalogue, but it features Neil's first recorded drum solo in the sub-section of 'The Fountain Of Lamneth: II. Didacts And Narpets'. It includes so many of the styles that would become staples of his live solos and was an incredibly important moment for him as a drummer."

2112 (1976)

"The breakthrough album for the band and a masterclass in Neil's drumming - especially the first two passages, 'Overture' and 'The Temples Of Syrinx'. You are not considered worthy if you can't air drum 'Overture'! Right to the end it was a key part of their live show, and that big opening tom fill at the start of 'The Temples Of Syrinx' is typical, and classic, Neil. 'A Passage To Bangkok' is also great. This was the start of their true prog era, and the next five albums that followed are my absolute favourites.."

A Farewell To Kings (1977)

"One of the all-time Rush greats, and an album that took drumming to a whole new level. 'Xanadu' and 'Cygnus X-1: Book One: The Voyage' are pure perfection and true prog classics. 'Xanadu' is quite possibly one of their best songs, and 'Cygnus X-1' gives a real sign of what was to come, as this track pretty much expands to an entire sequel on the band's next album."

Hemispheres (1978)

"Rush's progressive peak, and my personal benchmark in terms of virtuosity, musicianship and how far you can take it... I spoke in depth about 'La Villa Strangiato' in Rhythm last year (Tracks That Inspired A Generation, Issue 293), but the whole album is an exercise in pure indulgence (as they called it). 'The Trees' - my goodness, the drumming on that is just ridiculous. Masterful and musical, and the odd time signatures in 6s and 7s are an education in phrasing. There is so much there..."

Permanent Waves (1980)

"Just when you thought that they had peaked, along comes Permanent Waves to usher in a new decade for the band, and it's the perfect mesh of prog and sensibility. If I had to pick a favourite Rush album, this would be it. There are only six songs, and I look at them as three different animals. The Spirit Of Radio' and 'Freewill' are the radio tracks, and they got lots of airplay, but that didn't mean that the musicality was turned down. Rush did as much in five minutes on each of those songs as most bands would do in 20! They are drumming masterworks, but are also easily digestible. "The understated 'Entre Nous' and Different Strings', are equally great, and then you have the two heavy-hitters that close each side of the record -'Jacob's Ladder' and 'Natural Science'. The composition of these is epic and showcases some of the greatest drumming of Neil's career. I have covered dozens of Rush tracks over the years, but 'Jacob's Ladder' was one of the hardest. That middle section that alternates between 6 and 7 is so masterfully crafted, and the way that Neil develops the part and jams within it is just incredible. To craft every nuance of those grooves, beats and development shows such discipline; he really did have the mind of a professor."

Moving Pictures (1981)

"Their most popular album, an undeniable masterpiece from start to finish, and the record that changed everything and turned Rush into a fully-fledged arena band. Side one is complete perfection, and somehow it also translated to the mainstream, because Tom Sawyer', 'Limelight' and 'Red Barchetta' all became radio staples, while 'YYZ' became the band's most famous instrumental. "On side two, 'The Camera Eye' is one of my favourites of their more epic songs, 'Witch Hunt' is so dark and 'Vital Signs' is incredibly forward thinking-with the reggae influence that The Police were introducing around that time. It was to go on and become something bigger on the next album, but here it was ushering in a new era..."

Signals (1982)

"The height of my fan-boy fanaticism, the first tour that I saw them on and that red Tama drum kit that I reproduced for my Rush tribute years later! Here, they brought in more keyboards, and the songs became shorter and a bit more traditional in their arrangement. Neil's playing in 'Subdivisions' and the way he is grooving and phrasing in 7 is mind blowing. The highlights for me are The Analog Kid' and 'Digital Man'. Even though I went in different musical directions after Signals, there are moments on every subsequent album that I love, right up to Clockwork Angels. "As a band, and as individual musicians, Neil, Geddy and Alex were always developing, growing and embracing new influences and challenges. And, as a drummer, Neil was never content to stay in the same place - introducing electronics, new setups and sounds, scaling down to a single kit, relearning his whole approach with Freddie Gruber, playing swing and big band .. He was, and always will be, a constant source of inspiration. "RIP, Professor."

Memories Of Neil...

Rob Wallis (Founder, Hudson Music)

"What was it like to work with Neil Peart? Well, the best answer I can give is that 1 + 1 = 3! Neil referred to us as 'collaborators', and every project we worked on always morphed into so much more than we could ever have imagined at the start. A great example is the final one we did together - Taking Center Stage: A Lifetime of Performance - where we ended up with a three-part DVD, over eight hours in length!

"Our first adventure together, after getting to know Neil when we filmed a Buddy Rich tribute concert in NYC - Neil's first live foray outside of Rush - was the Burning For Buddy sessions that Neil produced for Atlantic Records. For 14 days straight we filmed the world's top drummers, and that brought us much closer with him. Eventually, we wore him down, and he said yes to doing his first instructional video - A Work in Progress - filmed in beautiful Woodstock, New York. We soon learned that an enticement for Neil was the locations we chose for filming, so we'd always allow him to make the final decision on any location. Neil would then match it up with travel plans that he would look forward to, either by car - he once had his limited-edition Z8 BMW shipped to my house outside NYC from the West Coast - or by motorcycle, driving from Woodstock to his home in Canada on his trusted red BMW. Just like the planning of a Rush tour, it all worked around Neil and his wish to see the most scenic parts of the country.

"I learned early on that Neil liked to have a hand in every aspect of a project. And he was always right - a perfect partner. He treated each production with the same care he treated his writing and his drum parts for Rush; everything had a place and a sound reason. Seeing our products on display at the merchandise stands at Rush concerts was something I'll never forget.

"Of course, all of his speaking on camera was equally perfect; I can barely remember a second take for any speaking and, for that matter, any drumming - of which we recorded hours! Everything he said was thought out and clear, all the way down to the detailed orchestrations on the drums on songs like 'Subdivisions', 'Caravan', 'YYZ' and many others.

"During the course of working with Neil for over 30 years, very little was off limits - except his private life. Neil was immensely private, and I feel very privileged to have been allowed into a small corner of his world."

Rhythm subscriber, Giles Henshaw

"For me, like thousands of other drummers around the world, Neil was a huge influence. His intelligence, technique and musicality continue to inspire and he is very sadly missed.

"As a spotty, young drummer in the '80s, I wrote to Neil - via Modern Drummer magazine - asking him about the Rus track 'La Villa Strangiato' and how to play it. Not expecting reply from my drumming hero, I resigned myself to practice the track without guidance, getting it wrong every time!

"Fast forward six months and, totally unexpectedly, one cold October morning what should drop through the post box than a handwritten postcard from The Professor himself!

"It was one of the many personalised cards that he use to send out to fans during the early '80s, until it took up to much of his time and he had to stop.

"Needless to say, I was thrilled, stunned and amazed that he would take the time to write a response to a kid fan in the UK.

"It remains to this day my most-prized drumming possession - it sits in a frame in my drum room - and is a lovely example of the humility of a truly inspirational drumming figure."

Beyond the Engine Room (Doane Perry, Jethro Tull)

"Neil and I may have first met because we both had the same 'day job' description - playing challenging music with our respective bands - but we connected in a way that went considerably beyond the wood and metal.

"Both of us loved the subtle and powerful art of language, and we would often write each other long, tall tales from the road. There was a mutual understanding about the challenges of touring and the cerebral, athletic and musical requirements of our respective gigs. When we got off the road, we would have these long, luxurious lunches, talking broadly across multiple topics and everything time would allow: literature, science, history, philosophy, astronomy, nature, exotic cars, obscure musical influences, the state of the world and the state of us in it. Generally, we would bypass the small talk and jump straight into these wonderfully labyrinthian conversations, sometimes finishing each other's sentences as we went along. Perhaps one of the reasons we connected in such a profound way was due to our shared interests outside of music, which informed what we both did inside music, even if they were only tangentially connected. Oddly enough, the common ground that originally brought us together rarely drifted into technical talk about drums. Never deliberate... it just didn't come up that much. There were always big notions to explore!

"Whether it was through music, lyric or prose writing, Neil was an exceptional, imaginative and exacting architect of language and rhythm. However, I don't think that artistic part of his being would have unfolded in quite the same way if it hadn't been for the deep humanitarian instincts that were always alive in him. That empathy and sensitivity was clearly present in his writing and, of course, in his playing with Rush, as well as every other artist with whom he worked. Those personal and artistic identities were inextricably linked, and I believe it's why he was able to connect with people so powerfully and directly. His natural gift of being able to put himself out there, without pretence, in such a revealing way, allowed people to really feel like they knew him. It was an honest reflection of who he was... and he never sidestepped the painful moments in his life, as he could so easily have done.

"People sometimes made the mistake of thinking that because Neil had such an extroverted personality on stage, that he was the same way off stage. He wasn't... he was actually somewhat shy, but underneath that stoic shyness (which was a mixture of modesty, humility, self-effacement, unapologetic honesty and near-military punctuality), was his constant desire to get better and to communicate more clearly. Even though there was much he kept in reserve, I feel it was also important to him that he felt clearly understood. Later, when he wasn't talking as much, he still remained deeply engaged with his family and friends. It wasn't always verbal, and even in those rare and hard to imagine quiet but comfortable moments between us, there was much that was communicated... and I know that was the same for others in his life.

"By default, he lived in the deep end of the pool. One afternoon, a small remark he made provided an illustrative insight to the rich interior landscape that he inhabited. I had given him a thick book by brilliant naturalist author Allan Schoenherr entitled A Natural History of California. He turned to me and said, "You know, Doane, this is where I live". It remained a permanent fixture on his coffee table. Although he never subscribed to any organised religion and had difficulty aligning with such a concept, he clearly belonged to the church of the natural world. I believe it was here, quietly communing in nature, where he was spiritually most alive and at ease.

"There are many valid perspectives here, as Neil knew and deeply touched countless people, some in overlapping circles and others in circles that barely crossed. Nonetheless, all of us who knew him could honestly say that we were extraordinarily fortunate to have shared the same time and space with him. And in that sense, I think he also belonged in part to everyone who loved and admired him, from up close or at a distance. I know he was deeply appreciative of the love and respect that was so deservingly accorded to him, and he never took that for granted.

"A consummate gentleman and genius musician, he was powerfully driven by a work ethic guided by integrity and excellence and worked harder than just about anyone I've ever known. Part of the reward for that hard work was that he lived a dynamic and BIG life... Not always easy, sometimes agonisingly difficult, but colourful, eventful, rich... and epic. "During his last years, I recall him telling me that he felt he had said pretty much everything that he had wanted to say artistically. However, knowing him, I think there would always have been more - but the comforting thought of having left a meaningful and substantial body of work behind, made him feel he had lived his life well and with clear purpose.

Without question, Neil was a "one-off" who possessed an extraordinary heart and mind, combined with a singular, original talent, an incredibly dry sense of humour and a lovingly generous, loyal spirit. Dedicated and passionate about everything to which he applied that exceptional brain - grace, success, eloquence and excellence would have followed him in whatever path he had pursued in life.

"Over our 30-year friendship, he became like a brother to me - and although our 'day jobs' brought us together, our friendship went considerably beyond that. I miss that, and I miss him."

Lorne 'Gump' Wheaton (Neil's drum tech)

"It was in 2000 that I got a call from Rush's then-tour manager, Liam [Birt], to see if I'd be able to help them make a record. Neil was coming back after the tragic loss of his wife and daughter, and because I could cover everything in the studio, I was going to be the only tech for the whole session. For me, it was like going back to family... I'd known Geddy [Lee] and Alex [Lifeson] since high school in Toronto, and, after Neil joined, had toured with them while I was working with Max Webster. I actually have Geddy to thank for my nickname, 'Gump'!

"I'm so proud to have helped them singlehandedly with Vapor Trails - it was an incredible process to be part of - and working for Neil was wonderful from the off. He trusted me to be his ears in the control room when it came to drum sounds on that record, and it was great to see him starting to enjoy the whole process again. Alex and Geddy were so happy to see Neil comfortable in his 'office' doing what he did best: experimenting, creating and writing lyrics. His brain worked like no other drummer I have ever known, and the parts he came up over the course of his career are just incredible.

"While we were in the studio for that year, I did a lot of work with Neil in updating his gear. There was the new Red Sparkle kit and hardware from Drum Workshop, and he started using Roland V-Drums and in-ear monitoring for the first time. It made his whole configuration more friendly for the both of us, and we ended up using that setup on the Vapor Trails tour. When it came to building kits with DW, John [Good] and Don [Lombardi] didn't have 'no' in their vocabulary, and the results were truly mind-blowing!

"I was taught how to tune drums by Steve Smith - one of the very best - and the timbre matching that John Good does with all his drums before they leave DW made Neil's kits easy to tune and bring up sonically. We tended to tune to the note stamped inside the shell at the factory, but I'd always crank the smaller toms up higher, to get that early Rush concert tom tone on the closed 8", 10" and 12".

"You'd think because Neil hit so hard that we'd go through drumheads quickly, but surprisingly we didn't... That was thanks to Freddie [Gruber] and what he taught Neil. After those lessons, Neil's whole setup changed: he sat slightly higher on the throne, his snare drum moved up to navel height and the tom configuration opened up around him. Rather than punching through the drums, he played into them - almost like the sticks were dancing. He liked the sound of old heads, so, during soundchecks, I would rotate two or three on the drums that he hit most to wear them in. Even though the band were playing nearly three hours, I'd only change the snare head every three shows, which was unbelievable, really.

"When Neil was on the road, it was all about routine, and prior to every show he would warm up for exactly 20 minutes - always practising a little bit of his solo. I liked at least a couple of hours to put his main kit together, and then I would drive myself crazy checking everything. My 'station' was eight feet away from the kit, and I saw everything from my vantage point - it was the best place on earth to be.

"Neil and I bounced along very happily together for all those years - I knew how he liked things, and he knew that I had his back if anything went wrong. Because everything was locked down on the rotating drum platform, there was only one slim entrance to get inside the drum set if we did have a problem. Once, when we had a failure on the main R30 kit pedal, I remember Geddy turning around to be greeted by my arse as I tried to get in through the front of the kit! Some drummers would completely loose it when something like that happened, but Neil - even though he wasn't happy - kept it together.

"Neil gave his all, all of the time - never more so than on that final tour, which was hard for him physically. It's almost like he wanted to torture himself with a final workout by using those two different drum sets. He went from playing the modern kit that he'd had for 15 years to the retro kit that required him to go back to his old style of playing pre-Freddie, because everything was in different places. It was quite amazing how he got his brain around that, but he was such an intelligent man. So many of his buddies came down to The Forum to see that final show, and it was a pretty perfect night."

Chris Stankee (Global Artist Relations Director, Sabian)

"Neil was a creature of habit, and change for him was always calculated and deliberate, but when we developed the Paragon line, he finally had the chance to get the exact blend of modern and vintage that he wanted. Months of development went into those cymbals, and we started with the ride - such an important sound for any drummer, and an integral part of the equation when it came to Neil and Rush. He ended up using that ride for everything, and I still have it. I'll cherish it forever, and I'm delighted to be able to share it with other drummers when they come and visit Sabian.

"Neil always had two 16" crashes up front and used the one directly in front of him the most. When that would eventually break, he'd take the 16" to his left and move it down - he liked the 'broken in' tone. Eventually, though, I managed to persuade him to let us make him cymbals with a brilliant finish, that sound and feel that way right out of the box. He never changed that ride though, but because Lorne [Wheaton] cleaned it with cream every day, it ended up with the same sheen as the brilliant cymbals and fitted into the setup perfectly. Neil's 20" Paragon Diamondback Chinese - with the jingles on top - was really fun to develop, and I'll also always remember when Peter Erskine inspired him to move from his regular 13" hi-hats to 14s. The combination, and difference in tonality, of those 14" Paragons, and the 14" Artisans on the X-hat worked great, and you can hear them all over Snakes And Arrows and Clockwork Angels. To hear those sounds we developed together on a Rush record, so masterfully engineered by Nick Raskulinecz, and to have played a part in what Neil was using as his voice, was such an honour.

"Watching Neil at work in the studio was amazing. Knowing how composed his parts were on those early records, it was interesting to see him change his approach gradually in those later years and be open to improvisation and other people's suggestions. I'd watch him do multiple takes - where he'd completely change his sentence, colours and meaning - and then have the choice of what suited the song best. It was almost like he was drawing from his experience as a writer and lyricist - the expression of those ideas on paper - and doing the same thing with his drumming. It was especially noticeable with his solo, and when I would see several shows in a row, I could hear those nuances and the changes. His phrasing was impeccable, and over a scotch one night, I complimented him about how his phrasing had developed and how I felt he was turning sentences into paragraphs. He toasted me and thanked me for 'getting it'. It was exactly what he was trying to do...

"I had to tech for him once, and it was nerve racking to say the least. I had set him up in the studio before, so I kind of knew how things went, but all his stands travelled together in one giant case and nothing was marked. Gump knew it by heart, but I certainly didn't! Even though the snare head broke in the second song, it was an amazing experience. When you stood next to him and heard him play it was so powerful, because he hit so hard, but those massive strokes were so precise. He was able to draw the sound out of the drum kit in a way I'd never heard before, and his rim shots, on the toms in particular, were just incredible. One of the things that impressed me most about him was that as someone who was so respected, so entrenched in our psyche, he was always looking to develop and move forward.

"Unless he was on tour, or getting ready to go into the studio, Neil didn't play drums. To watch him regain his voice, power, joy and passion every time he and Lorne headed off to Drum Workshop to rehearse was just magical. That smile got bigger and bigger as the dust blew away...

"I'll never forget standing at the top of The Forum in LA with him after Rush's final show, watching the stage come down for the last time. He had an impish smile on his face, and he was happy. He realised that it was over - no words were necessary - and to share that moment with him in the empty arena, as the after-show party raged inside behind us, was very special. His development was done, and I think it's important for his fans to know that he did allow himself to enjoy everything that he achieved before he left us..."

John Good (Senior Executive Vice President, Drum Workshop)

"Neil was quintessentially the epitome of family to Drum Workshop, and he felt so at home here. Every new tour was a new adventure for the two of us, and all the drum sets we built together were complemented by his style, his playing, his absolute attention to detail and his love of making a visual, and a sonic, statement of what he did. And he always pulled it off.

"I still smile when I remember the first time he came to visit... We'd never really met, but I knew that he was a very private person, and I had asked our production crew to give him space when we took our tour. Neil was fascinated by the factory - it turned out to be a very long tour! - and he was intrigued by all of the intricate details that make my heart pump when it comes to building drums. When we got back to my office, though, he asked if people here disliked him, because he hadn't been able to catch anyone's eye and nobody had really spoken to him! When I explained what I had done, we both laughed out loud, which broke the ice completely, and from that point on he became a regular visitor. So much so, that he started using our studios to rehearse in before each Rush tour. His gear would turn up, and then Neil and his tech, Lorne, would lock themselves away for weeks before he met with the rest of the band. He was always super prepared and would practice for hours. We even gave him his own parking space for his bike, or his silver-grey Aston Martin - the cutest little car for such a big man!

"Neil and I would talk constantly about the next project, and he always wanted to blow the previous kit away! I remember after the Vapor Trails tour, he sent the kit to my showroom so I could study and play it and see how it was tuned. Neil hit so hard, but because he hit 'right', he was pulling the sound out of the drums rather than wrecking drumheads. His drums were tuned not to the shell, but to the notes that he liked to hear, so what I got into doing was creating a shell that would deliver that note without torture. You don't have to tune something way up or way down - where it doesn't want to be - to get the right note. So, year after year we continued to plan and build new kits for him - works of art, really - that he loved, and I became known as the 'Wood Whisperer'!

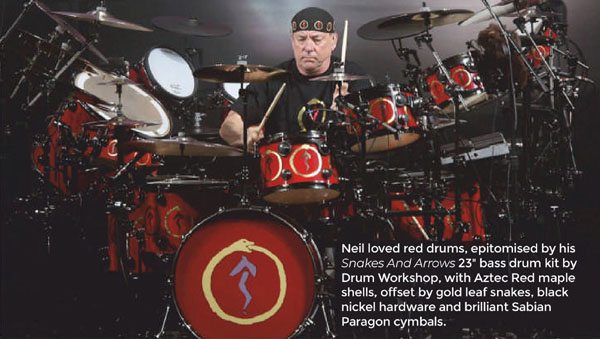

"One day we happened to have a conversation about bass drums, and Neil told me how he liked the sound of a 24", but that he couldn't get the articulation he was after when he played one. That's when I developed the 23" for him - something I had always wanted to build - and Lorne and I managed to slip it into his kit at rehearsals without him knowing. He was over the moon, and that's what he played from then on.

"I visited Neil when he was ill and no longer able to drive himself, and he told me how he enjoyed a ride with his driver every day and that they would listen to three songs on the way out and three on the way back to the house. I asked him what music he was listening to and he said, 'Rush, of course! You watched me prepare for tours, for recordings - I was always prepared - but what I failed to do was actually listen to the music as a whole. I was so buried in my parts, wanting to make them the very best that they could be, that I never really listened to the band. And do you know what, John, we were pretty good!'."

The Drum Sets Of Neil Peart

A tour through the evolution of Neil's dazzling kits, from his first MIJ set all the way to his R40's 'El Darko'

By Geoff Nicholls

A major part of our fascination with Neil Peart concerns his drum kits, which rank among the most talked about, ever. So, in this corner of our tribute we highlight some of the major stages that led to his ultimate setup. We aim to present a flavour of the relentless endeavour behind a lifetime quest.

It would be impractical here to detail all his kits - they would more than fill the magazine. Luckily, since his fans are so devoted, you can find forensic details online. For a mind-blowingly full account, visit: https://bit.ly/3oZBnEq

INSPIRATIONS

Peart himself name-checked umpteen drummer influences over the years. But as a youngster, his imagination was sparked and shaped by Gene Krupa in jazz and Keith Moon in rock, both of these rascals making a huge impression with their unrivalled showmanship.

Although serious and studious where Moon and Krupa were outrageous and outgoing, Peart nevertheless determined to put the drummer centre stage in his own way. He would develop an elaborate style, necessitating a hugely extended kit. Thus, he inspired thousands of drummers via the spectacle of his mega setups, through which he determined to muster every bit of tonal colour, especially in his solo pieces.

BEGINNINGS

Neil signaled a lifelong intention to take his instrument seriously when he spent his first year labouring over a single drum pad. As a reward, aged 14, he got his first kit, a budget Stewart three piece - a so-called MIJ (Made In Japan) "stencil" kit, badged by Pearl (see this month's 'Vintage View').

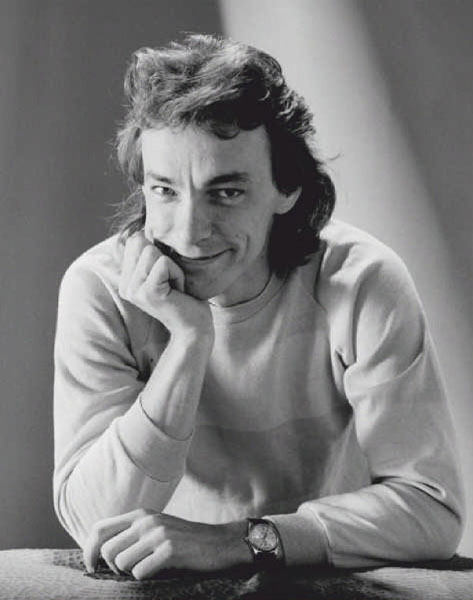

It was in red sparkle and presaged his enduring taste for red drums. Having said which, his first pro kit, a couple of years later, was a mid-sixties Steel-Grey Ripple American Rogers, in small 20", 12" and 14" sizes. He had a penchant for small sizes early on, although he quickly found his liking for slamming the drums hard.

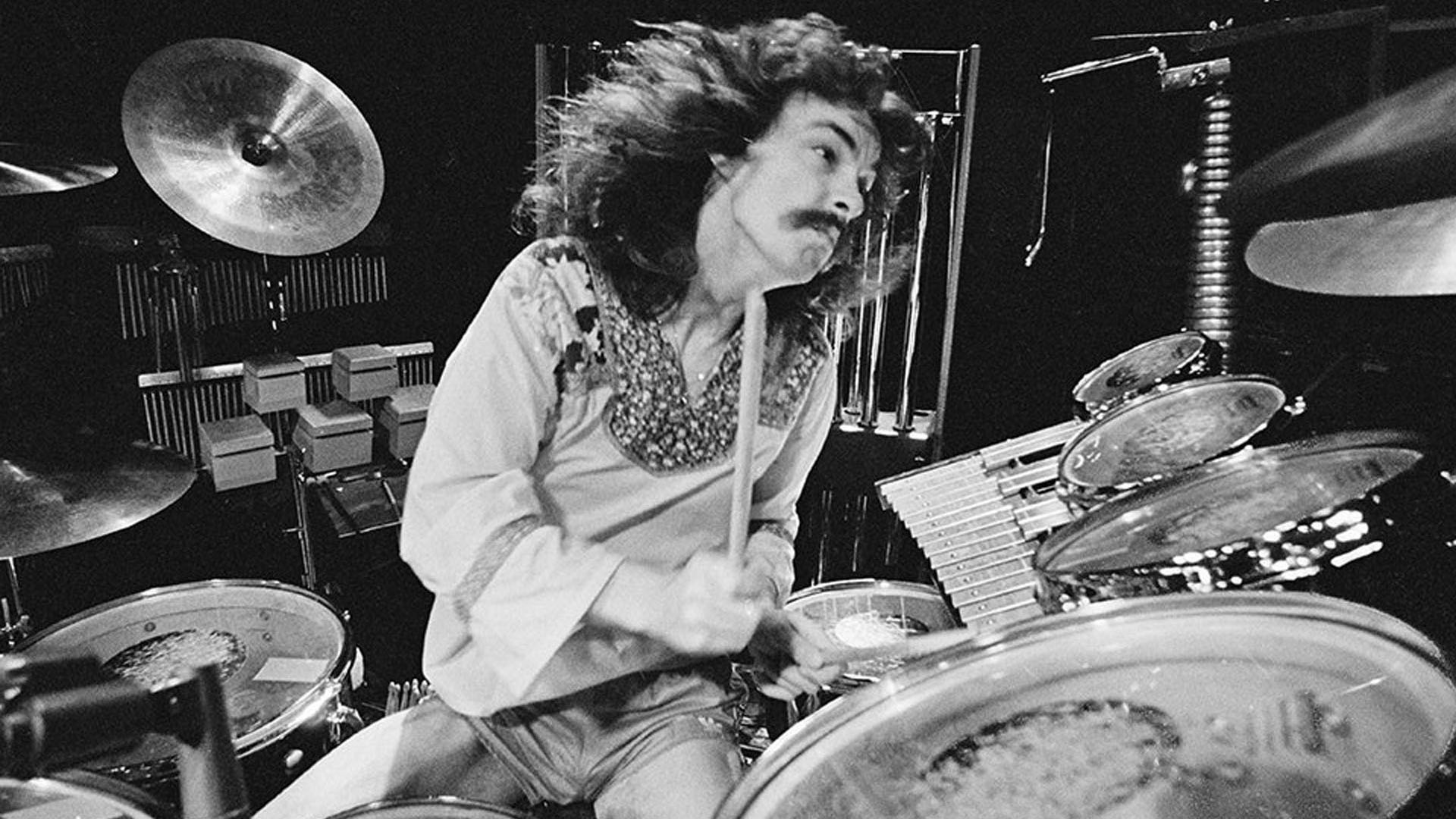

He soon added a second bass drum, an essential part of the post-Ginger Baker and Keith Moon look. Ginger was the inspiration for every drummer to take the rock drum solo to a new level. Neil told Rhythm in March 2014: "Ginger Baker certainly opened the floodgates with 'Toad', the vehicle for my own first solos".

But since Rush became an unashamedly '70s prog rock band, their musical antecedents were the British originators: King Crimson, Yes, Jethro Tull, Genesis and ELP (Emerson, Lake and Palmer), all of whom had drummers whose styles and qualities would bend Neil's ears. Michael Giles's pinpoint snare drumwork on Crimson's '21st Century Schizoid Man'; Bruford's pioneering use of electronics and odd times; Phil Collins's crowd-friendly multi-tom solo features - incorporating elements of all these (and numerous others) meant that Neil inevitably had to formulate bigger and bigger kits.

Historically, however, it is the bombast and bravura of Carl Palmer that is closest to the Peart model. Palmer's tuned percussion, classical side drum technique, his mammoth solos on a revolving stage incorporating acoustic and electronic elements - all found their way into Neil's armoury. And ELP was a trio, like Rush. Carl led the trend for fabulous custom kit in the first prog era, but Peart fans should know that his antecedents can be traced all the way back to Sonny Greer in the 1930's Duke Ellington orchestra. To do justice to Ellington's sumptuously orchestrated pieces, Sonny assembled a custom-graphics finished drum set alongside chimes, timps, vibraphone and gong on a riser that rivals even that of Neil. Sonny surely would have loved Neil's sets. And in his first Rhythm interview back in March 1987, Peart himself had this to say regarding his then-Tama setup: "I look on it was my own personal orchestra that I can orchestrate and conduct".

NO RUSH - THE SLINGERLAND ERA

(1974 to 1979)

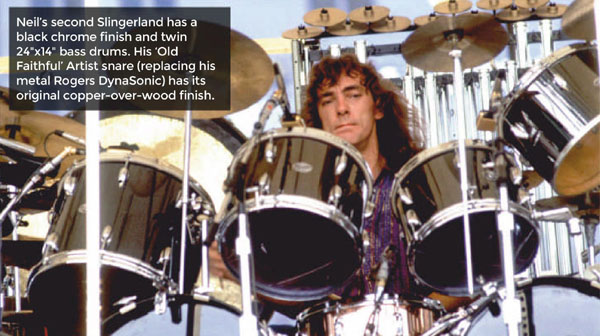

In 1974, Neil joined Rush and began his association with Slingerland. American companies were still riding high - Slingerland claimed to have the world's biggest state-of-the-art, custom-built factory, and Buddy Rich and Gene Krupa were the company's star endorsers. Slingerland's full-colour catalogues around this time were drop-dead gorgeous. Chrome and copper-clad drums were the stars, and the cover of the 1973 catalogue is emblazoned with a show-stopping doublekick copper clad Concord kit.

Accordingly, Peart bought a chrome-over- wood kit in larger sizes: two 22"x14" kicks, two 13"x9" mounted toms, plus a 14"x10" and 16"x16" floor tom. Keith Moon had previously played a chrome kit, so it was a cool, modern look. Cymbals were Avedis Zildjians: 13" New Beat hi-hats, 16", 18" and 20" crashes and a 22" Ping ride, a favourite for the next three decades.

OLD FAITHFUL 'NUMBER ONE'

Shortly after, Neil found a copper-over-wood Slingerland snare - acquired secondhand for $60! The previous owner had filed down the snare beds, resulting in improved response at all dynamics. This thin (three-ply, eight-lug) wood-shelled Artist model snare became his go-to, especially live, right up till his DW years in 1994. He even repainted the copper covering to match some later kits.

CONCERT TOMS

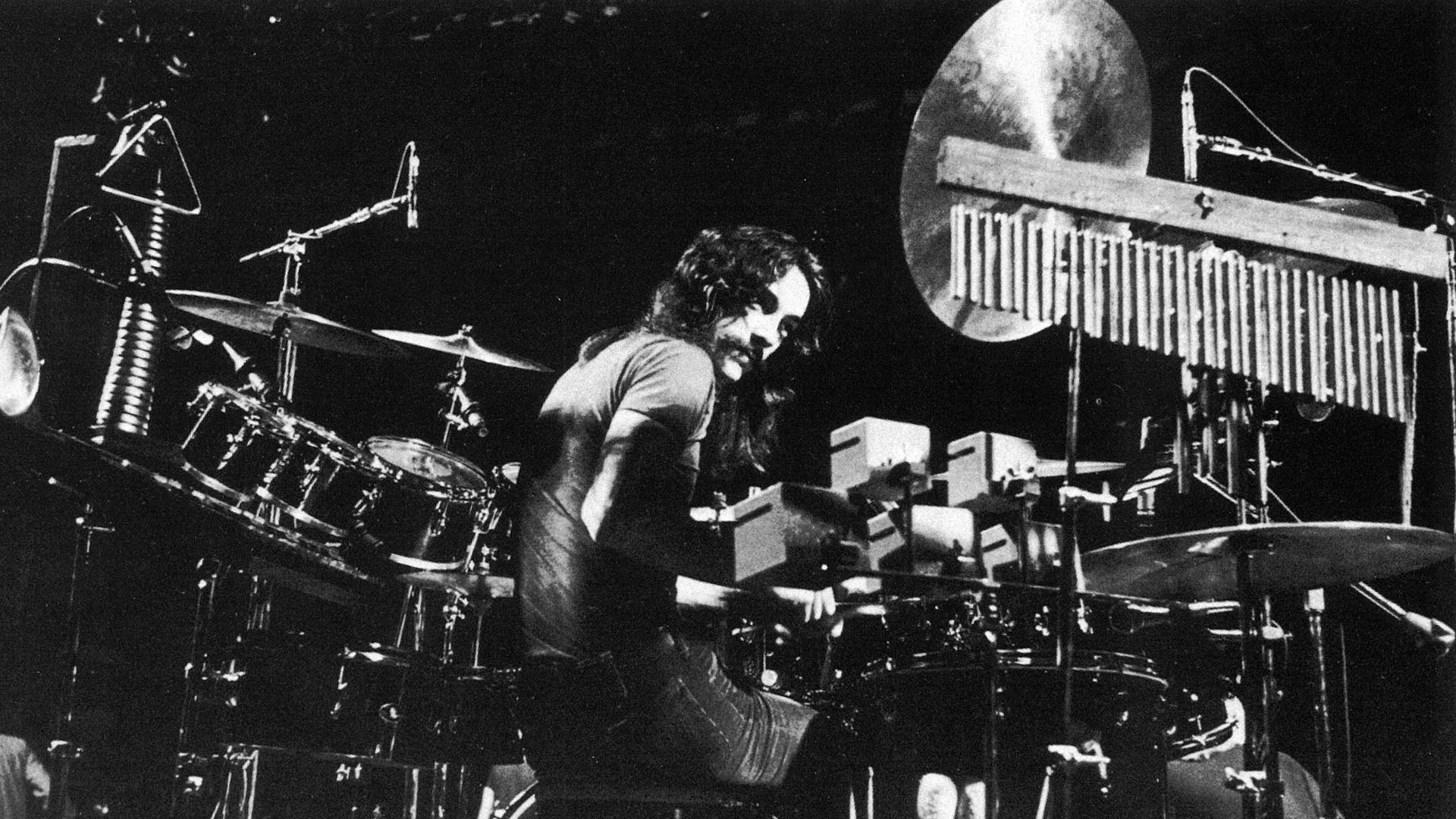

For the Caress Of Steel tour in 1975, Neil expanded his palette with four single headed concert toms, plus the inclusion of various items of percussion: temple blocks, tubular bells, timbales, wind chimes, bell tree, triangles and a glockenspiel.

The concert toms were mounted high up to his left and tuned high to give a broad sweep of pitches all the way down to the floor tom - a feature that quickly became synonymous with the drummer. More and more drummers were intrigued by this, and he garnered many more fans.

The evolution continued as the bass end was bolstered with twin 24" diameter kicks while applying a fibreglass coating the insides of the drums - a bit like Pearl's famous WoodFibre series of the era. This process of "VibraFibing" was undertaken by Percussion Centre of Fort Wayne, Indiana. The theory was that it evened out and sharpened the tonality. Peart later admitted that he was not sure if it did much, but it certainly didn't do any harm.

THE TAMA YEARS

(1979 to 1987)

As the '70s came to a close, the American drum companies were sinking fast and the Japanese coming on strong. None more so than Tama, with the input of the revelatory Billy Cobham. Tama's toughened hardware made the outmoded American staples look tired and transformed the modern kit, while Cobham's rediscovery of the mounted gong bass drum also caught Peart's eye.

With Tama willing and able, Neil made the inevitable switch. His first kit was stained "a dark rosewood effect", apparently inspired by his own household Chinese furniture. This was the first of his custom finishes - and also the first with brass- plated hardware.

Tama's birch shells were quite thick, and, following a chance 1981 studio encounter with the thin shells of a vintage English Hayman kit (belonging to Corky Laing of the band Mountain), Neil suggested Tama try something different.

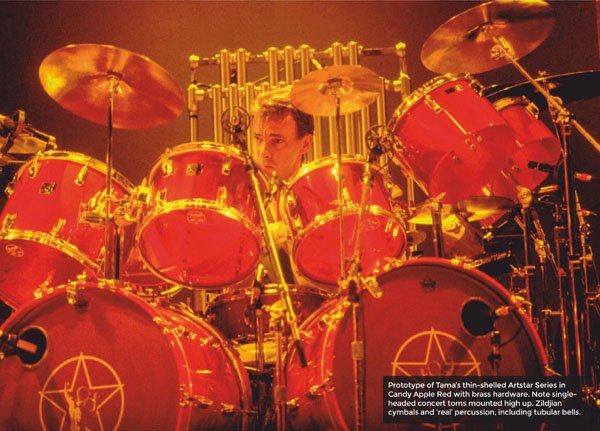

Accordingly, for the 1982 Signals album and tour, his new Candy Apple red finish kit, again with brass hardware, had thinner shells - prototypes of what became the top-line Tama Artstar.

NEW ERA ELECTRONICS

The early '80s saw the arrival of drum machines and electronic kits as the computer/digital technology upheaval gathered pace. Accordingly, Peart was able to start swapping his fiddly real percussion instruments for handy electronic substitutes.

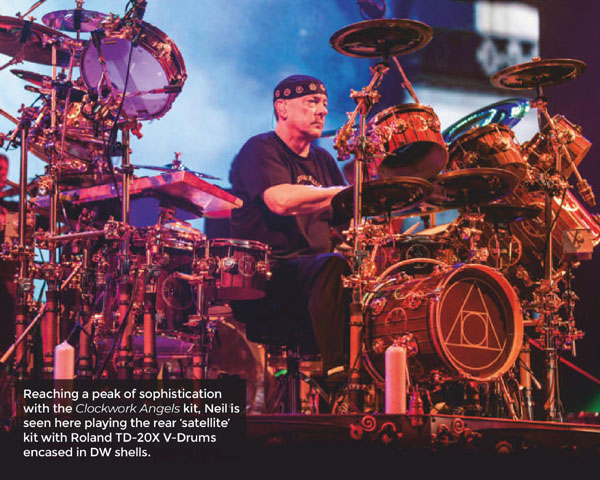

However, this was early days, so the Simmons SDS-V brain/pads and Shark trigger pedals shared space with a mini acoustic kit. This latter incorporated an 18"x14" Tama acoustic bass drum and a full set of Zildjians in a rear-facing 'satellite' kit. For 1984's Grace Under Pressure tour, Peart played 'Red Sector A' on this satellite kit with his back to the audience, hastening the necessity for a revolving riser. Henceforth, both acoustic and electronic setups would revolve to face the audience: the ultimate Peart setup that would thrill audiences for decades. Also, as digital sampling technology proceeded, Peart was quick to start making his own unique samples, which he would continue to expand on for the rest of his career.

Incidentally, the erection of the later two-sided kits was an event in itself. All stands were made to screw into special receivers precisely located in the 9'-by-9' octagonal riser platform boards. There's fascinating footage of this here in a video showing the setting up of his kits at Red Rocks Amphitheatre in Colorado : https://bit.ly/3eucEDb

ALL CHANGE AGAIN

However good the Tama kits, it is clear Peart was always looking for the next challenge - both in his playing and his search for the ultimate sounds. I'm old enough to remember when he announced in Modern Drummer in May 1987 that he had tested out six alternative makes of kit. And it was a pleasant surprise when he concluded that the then-somewhat unfashionable Ludwig was the chosen outfit for his next phase.

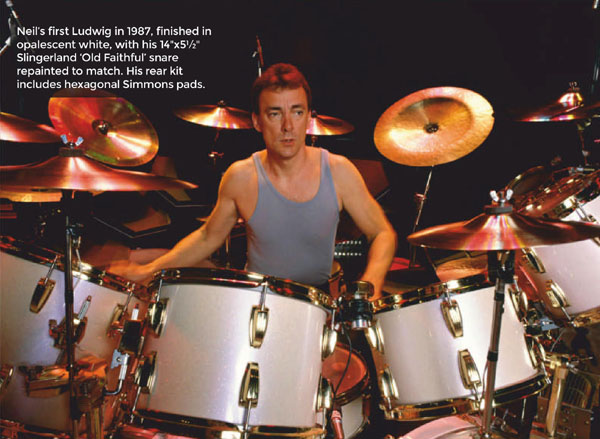

This boosted Ludwig's prestige at a time when the company was somewhat languishing, no doubt hastening its return to favour. The resulting Super Classic kit is my personal favourite of the entire pre-DW era. The pearly white opalescent finish and the brass-plated Ludwig Classic lugs, combined with classy bass drum graphics, made this kit the shiniest of his career - a surprising contrast with his mostly darker red kits.

He stuck with his Old Faithful Slingerland snare also, getting it painted to match the rest of the kit.

DON'T LOOK BACK

By this time, Peart had acquired a large number of big drum kits, and it seems he was not overly sentimental in disposing of some of them. He'd already given away his first Tama in 1982 via an essay writing competition in Modern Drummer, and now (this time via a drumming competition in 1987) he would give away two Slingerland chrome-clad kits and his Candy Apple Tama. Plus, the satellite Simmons e-kit was thrown in. So out there are some lucky owners!

He was practical, too, not just ordering new kits simply because he could. He occasionally got a kit repainted when presumably he could as easily have got a new set. If the drums still sounded good, he would stick with them and refurbish them.

INTO THE NINETIES - DOUBLE TO SINGLE KICK

With another new decade and 1991's Roll The Bones came a major new development. Kick pedal construction had improved to the point where many drummers decided that just the one bass drum fitted with a double pedal was the smart way forward. Peart had been waiting for this to happen, and he now changed his twin 24" Ludwig kicks for a single 22"x16".

For years, Neil's double-kick setup had been the epitome of the post-Ginger Baker/Billy Cobham/Keith Moon model. But after he rationalised his setup to a single kick, it took on a distinctive sculpted shape with that dramatic sweep from elevated top left to bottom right, which became synonymous with the drummer and part of his persona.

After seven years, Neil's third and final Ludwig kit had a Black Cherry finish and was seen on the band's 1994 Counterparts album and tour.

TRAIL-BLAZING WITH DW

The final chapter in Neil's pursuit came with the move to Drum Workshop in 1995. There was an element of inevitability in this, what with Neil's restless searching and DW's willingness to experiment. It felt like he had found his home, and indeed, his first Test For Echo and Vapor Trails DW kit was in red sparkle, like his first Stewart kit all those years before.