Geddy Lee on Rush's Prog-Rock Opus "Hemispheres": "We Had to Raise Our Game"

The bassist reflects on writing side-long "mini rock operas," singing in awkward keys and Alex Lifeson's mysterious "bedroom accident" - and offers an update on the state of Rush

By Ryan Reed, RollingStone.com, October 22, 2018

"There's your bizarre dog tale for the day," says Rush's Geddy Lee, prior to a lengthy conversation about the band's 1978 prog-rock opus, Hemispheres. But the bassist/vocalist isn't referencing, say, the jagged riffs of "By-Tor and the Snow Dog" - instead, he's detailing a bizarre injury that his two Norwich Terriers, Stanley and Lucy Wasserman, recently suffered while chasing a squirrel.

"I was away in the U.K. and got a call from my housekeeper, saying they both tore a tendon in their knee at the exact same moment," he says. "She took them to the doctor, and one of them tore the left knee ligament, and the other one tore the right knee ligament. Isn't that just the strangest thing?"

In a roundabout way, it's a fitting start to the interview. Much like the musician's scurrying dogs, Rush - Lee, guitarist Alex Lifeson and drummer Neil Peart - found themselves on a wildly taxing pursuit while crafting Hemispheres, which Rolling Stone named the 11th-greatest prog-rock album of all time. "Let's say our ideas exceeded our grasp," Lee says of the LP. "And we had to push ourselves and raise our game, which took longer than expected."

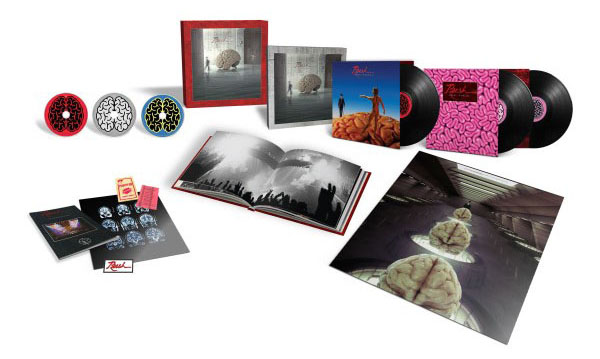

The Rush frontman is promoting the upcoming 40th-anniversary reissue of Hemispheres (out November 16th), which includes a 2015 remaster, a new 5.1 surround sound mix, promo videos and a previously unreleased 1979 performance from the Pinkpop Festival in the Netherlands. The record marked a pivotal point in the Rush chronology, perfecting the extended conceptual aesthetic they'd explored in the mid-Seventies before they reined in their songs with tighter structures on 1980's Permanent Waves.

In his conversation with RS, Lee reflected on the album's endless creative and practical challenges. Along the way, he also discussed his upcoming bass book, the possibility of future solo work and the current state of Rush - who, in 2015, concluded what could be their final tour.

Let's start off at the beginning. So you guys came into the Hemispheres writing sessions without any pre-conceived ideas and just sort of worked things out over a four-week span?

Something like that. We grossly underestimated our time for this project [laughs].

Were you just drained of riffs at that point?

That actually wasn't the case. The case was we had booked this studio time, and I believe we came straight there from tour. We were meant to record at Rockfield Studios in Wales, so we'd booked a little time at this house that they sort of used for their bands. We thought we'd do some writing and pre-production there and move into the studio to record. But I think we greatly underestimated the level of overachievement that we were shooting for. As we started writing, it became apparent that this was going to be a concept album, and then it became even more apparent that the musical attitude was going to be quite complex. That was our mistake: It wasn't that we were bereft of ideas - it's that the ideas we did have were much more ambitious than we gave credit to.

We found ourselves working diligently and quite hard, but we underestimated the amount of time it would take to put that thing together. We increased the amount of time we were in pre-production, and then we finally went into the studio after about four weeks. That was a very ambitious recording, and we wanted to do most of it live off the floor, and that meant that we had to be f'ing perfect [laughs].

These were long pieces of music. "La Villa Strangiato," for example, we wanted to record that in one long, perfect take. We tried for days to get that, and eventually we had to compromise. We did it in four segments and stitched it together. I think we spent something like 11 days on that track. I remember telling the story at one point that it took longer to record "La Villa Strangiato" than it did our entire Fly by Night album.

You'd gained some commercial momentum in 1978 after "Closer to the Heart" made a dent on the U.K. charts, but Hemispheres is one of the least accessible Rush albums ever. Did you have any initial ideas of striking while the iron was hot and making something more easily digestible?

Not really. We were not really practical thinkers. We never knew what was going to come out until we sat down to write. I would say that was, in a way, the biggest hindrance to mass success, but at the same time it was also our saving grace in a sense because everything we did was a natural reflection of who we were and what kind of players we were and what kind of dreams we had. Our albums really do reflect where our heads were at that particular moment. We didn't put much stock into commercial single success. We didn't really even know how to make a commercial single. Any time we attempted to do something shorter, it naturally became the single just by virtue of its length of time. We probably released more unsuccessful singles than any other band [laughs]. That wasn't really an issue. That wasn't present in our minds, the success with "Closer to the Heart." But really in the back of my mind was that we'd attempted a side-long piece before on Caress of Steel ["The Fountain of Lamneth"], and that just stuck in our craw as highly flawed, and we wanted to have another crack at it and do something more interesting.

What about that piece did you think was flawed?

It just felt somewhat naive. Obviously with "2112" we'd gotten it right. I related ["Cygnus X-1 Book II: Hemispheres"] more with what we attempted to do with Caress of Steel - that kind of ambience. They were all sort of mini rock operas, but "2112" stands as a rock opera that's much more rock to me. But this to me was a bit naive at times, and the dynamics were very extreme. And this was an attempt to do a more cohesive version of that. By the end, we felt we were falling into a pattern with these things. The albums after that were in rebellion to what we'd achieved with "Hemispheres."

Hemispheres is simultaneously the apex of Rush's full-blown prog style and a curtain call for that particular era. After that album, you recorded Permanent Waves, which fittingly kicks off the 1980s in a more accessible style.

Yes, exactly, that's right. It was the end of a thing. In a way, we felt we were starting to repeat ourselves, like when we put the overture together for "Hemispheres." We were falling into these patterns of writing - the repetition of these thematic things that occur over a 20-minute span. They were starting to feel too comfortably organized in a way, like we weren't thinking originally enough. That's kind of a prog pattern. People associate prog rock with a challenging style of music, and it certainly can be that. But if you're starting to fall into past habits and develop a methodology that's too comfortable, it's not progressive. I think we started to feel that way by the time we finished that record. With some of the experiments on Side Two, for example, like "Circumstances," we were able to work in a shorter time frame. That started to become more challenging and more enticing, so we sort of headed off in that direction.

In comparison to "Hemispheres," "The Trees" is relatively concise and melodic, and Neil's lyrics have sort of fairy-tale quality. Did Alex's classical guitar set the tone for writing in that atmosphere?

I think it was all inspired by the lyrics. As you say, it's this evil little fairy tale with a nasty ending. It was an example of writing to the lyrics and trying to do a soundtrack to that lyric. It's also the fact that we were out in the country and Alex always has an acoustic guitar nearby. He's an absolutely marvelous acoustic player. So it sort of seemed like an "English countryside" way to start the song [laughs]. You're definitely inspired by your surroundings wherever you're working. Even though you're working eight hours a day in a bunker, in between that you're watching English television, walking in the English countryside; there are sheep talking to you in the early morning when you're trying to sleep. The full bucolic ambience of the place starts to seep in. The lyrics came first, and we wanted to construct a dynamic little tale as a soundtrack to those lyrics.

The Toronto Sun wrote in 1978 of "The Trees": "The band had worked out a cartoon treatment of the lyrics in which giant complacent oaks would be arguing with bitchy maples, but it proved much too expensive." Is that true? Did any of that initial material survive?

Oh, boy, that sounds familiar, but it's been so long ago that I don't remember much about it. But in the early days we had a lot of ideas for enhancing our live show, and we were using screen projection from the earliest shows I can recall. We were always using it for something, even if it was just a Sixties-style, psychedelic liquid-light show behind us - whatever we could afford. As we grew up as a band, and as our music got more adventurous, we became painfully aware of how stuck we were to our stations onstage. So we felt it really important to keep the audience entertained in some way - if it can't be with us rocking out on our instruments, it would have to be through lights and sound and that kind of thing. It's entirely logical that we would have pursued a little animated piece to accompany it. Since you just mentioned it, it's sparked some memory, but I don't recall what actually happened. Alex might remember it more, but I was more involved with the animation and the live production. God, it does sound familiar. We never made anything like that, but I'm sure we went down the road and somebody said, "It's gonna cost X," and we went, "Oh, yikes!"

By this point, your technical abilities were so advanced that you could pretty much go anywhere creatively. But I've read that you didn't particularly enjoy playing the Hemispheres stuff onstage.

I don't think it was the complexity of the material that made it difficult to reproduce, and we never shied away from that. But it was a difficult record to sing for me - we'd written the whole thing in a sort of house where we weren't actually performing any of this stuff live with vocals. And it was happening at such a rapid pace that I'd sketch out, "Yeah, yeah, this vocal's gonna be here. That'll work. This melody works." And we just assumed that when we got all the tracks down and did the vocals, it would work a treat. When I actually got to record vocals, which was literally weeks and weeks later in London at Admission Studios, I came to realize that we'd written the whole album in an awkward key for me. So it was very difficult to sing. It wasn't so much that it was difficult to sing and play - that's just a matter of rehearsal. But singing at that range - even for my goofy voice - was a challenge. So I don't know that that album affected the writing style, and I don't think it was the complexity of the material that affected where we went. I really don't think that was a factor. What made it difficult to play huge chunks of live was the range it was in. And I wouldn't even dream in those days of transposing it to another key - that would have felt like too big of a compromise.

Has that been much of an issue in the past where you have to change keys to accommodate your voice?

Oh, yeah, we do that all the time now. That's the way you're supposed to do it! [Laughs] We just never had formal education. And our producer, Terry Brown, bless his heart, never once suggested, "Maybe there's a better key for you to sing in" [laughs]. Maybe that's one of the reasons we made the move [to work with new producers] not too many years later. But it was a huge lesson, and it was a mistake I made a couple times in my career - not doing enough diligence with what key you're playing in. So of course that was a huge wake-up call. Had we done that record in a different way where we had more time, it would have become more apparent. We never did demos in those days. We just wrote it and then recorded it. If you were doing a demo, that would have revealed itself - that this key was mental to sing in. So we would have changed it. But not doing a demo and just going straight in, recording and writing it, and then boom: The clock is ticking, and you're at Advision in London and you've been in London for over three months, and you're missing your life. It's like, "Holy crap, I have to sing this!" It was really difficult. So if anything limited the amount of time we played that suite afterward on tour, it was my desire to not sing in that key [laughs].

Few rock bands in those days were probably considering keys at all, and many wound up struggling with those keys years later.

It's true. That's one of the first things I learned from working with [Rush producer] Peter Collins - he took a very old-school producer's approach. I think that's why Rush did tend to look for producers. After we finally left Terry - which was a difficult decision for us because he was a mentor and sort of a father figure, or at least a big brother figure - the producers we looked for were all about, "What can we learn from this dude? What can I learn about arranging from him? What can I learn about songwriting?" When I worked with Rupert Hine, one of the big motivations for me was that he was so good with singers, and I learned a lot about singing from working with him. If you're not learning from your producer and you're able to second-guess what the producer is going to say to you, it's time to move on.

Terry is credited as a co-arranger on these albums. With Hemispheres, there's obviously a lot of material to arrange. How hands-on was he in that process?

We were putting the song together and would get to a certain point where we'd lose our objectivity. We'd bring Terry in and say, "This is what we have up until now. How is it hitting you? Is it working?" And he'd have suggestions: "This part goes on too long, or this part can be more complex. Or you've got this part in seven, and maybe it shouldn't be in seven." He'd look at the song from a fresh perspective and suggest improvements to it. So in that sense, he'd help the arrangement and structure of the song. Of course, when you get into overdubbing, he was really the most important sounding board as you're putting a vocal piece down or a guitar solo down or a keyboard part. As soon as you start playing it, you lose your objectivity. You need that guy behind the console who you trust to say, "That's not working. Why don't you try something different?" And they either have very specific suggestions or are very good at least pointing out what doesn't work. You can't always rely on a producer to solve the problem for you. I think that's fine: If you can recognize the problem, I can solve it. It's the inability to recognize it that produces bad work. A lot of guys don't require that. Some people are fully formed and don't require a producer to help them recognize that [laughs]. But no matter what I do, I like to have that. I like to work with a producer for that reason.

"La Villa Strangiato" was inspired by some of Alex's nightmares. And the subtitles are super vivid, like "Never Turn Your Back on a Monster" and "The Ghost of the Aragon." Do you remember any of those nightmares?

[Laughs] Oh, man. They weren't all that literal. With that album, we were waking up so late at night that we'd wake up in the early evening or late afternoon. We'd gather for breakfast and probably work until five or six in the morning and go to sleep with the [makes sheep noise] outside your window. Al would always greet us in the morning with, "You'll never believe this dream I had," and Neil and I would always - with hands in front of our faces - go, "Oh, my God, here we go." He would berate us day after day with these crazy stories of him driving an ocean liner down the street in Toronto. It wasn't inspired literally by particular dreams. It was inspired by his dreaming, period - and his style of dreaming. The Alex style of dreaming inspired "La Villa Strangiato," and I always considered Alex's brain to be "La Villa Strangiato" [laughs].

The Pinkpop gig included in the Hemispheres reissue is really impressive - lots of energy. Do you recall much about that set?

I don't know where they dug up all that material. I'd totally forgotten about any of that stuff being recorded. But I do remember the festival quite well for a number of reasons. This was one of our first and more expansive European tours, and I think something like four or five days before this show, Alex was involved in some sort of bedroom accident, and he hurt his finger. He hurt it so severely that he had this major blood blister under one of his nails and had to go have it treated, and he couldn't put any pressure on his guitar neck for a few days, so we had to cancel a couple of shows in Germany.

Just to clarify: Alex's hand injury was the result of a "bedroom accident"?

[Laughs] No one really knows what happened. He went into his bedroom with his wife one night, and he came out the next day with a fucked-up finger.

I may need to follow up with him about this.

[Laughs] Pinkpop was the first gig we'd done since he hurt himself, so the gig is very fresh in my mind. There were three stages. In fact, we played on the same stage as the Police, and that was just when they'd had a big hit with "Roxanne." They were the darlings of the festival. Peter Tosh was on that show. It was kind of a cool event, and the Dutch are great rock fans. We didn't do many festivals like that.

It also stands in my mind for another goofy story [involving] my keyboard tech at the time, Jack Secret [real name: Tony Geranios]. It was the afternoon of the gig, and we were just setting up and getting ready to soundcheck. There was a little wall on the stage, and Jack had probably smoked too many doobies, and he just hopped over the wall, assuming there was a floor on the other side, which there wasn't. It was a concrete staircase, and he dropped down this flight of stairs and broke both his feet. He had to be carried to the hospital tent and be treated, and of course he was my keyboard programmer, so they brought him back just before the show. Bless his heart, he was basically at the side of the stage, almost lying down and helping to get the show going. We did that show with him as pretty much an invalid, after this terrible accident. That's Pinkpop for me - I remember it pretty clearly from that perspective.

Wow. Everything from injured fingers to broken feet.

Yeah! I guess the gig went really well. I don't remember much about playing, but I remember thinking that I probably played well after that craziness. I'm glad there's some evidence of it anyway [laughs].

Based on the recording, you guys seemed to pull everything together.

That's kind of a miracle for me [laughs].

Now that Rush now appears to be in hibernation since the last tour, have you thought at all about recording another solo album? You haven't released one since My Favourite Headache in 2000.

I go down to my studio on and off, and whenever I pick up an instrument, something comes out spontaneously, and I try to at least grab a moment of it and stick it on tape and forget about it. I've been so busy the past three years with this book project [Geddy Lee's Big Beautiful Book of Bass, out December 4th], which consumed my entire being - which is fairly typical to my personality - that I haven't been thinking about another music project at this point. I say that, and at the same time, another part of my brain is always thinking about another music project. But when you've spent 42 years working closely with the same people and formed the kind of bond and friendship that the three of us have had - and maintained, to this day - it's a big decision and a big question what you want to do next. Or if you want to do something next.

These are fundamental, existential questions, and I cannot say that I've answered that question satisfactorily enough to move in one direction or another. Part of that is due to the fact that I have been so obsessed with [this book]. In a broader sense, it's a book about what the bass guitar means to me - and what the bass guitar means to music, especially from the years 1950 through the Eighties. So it was quite a fascinating endeavor and a great challenge, and in a way I welcomed this obsession into my life as a door. Obsessions are doors to other things if you're doing it right. It was a fabulous reeducation to the instrument that I've held in my hands for so many years but took for granted.

Is there anything at all you can tell us about the state of Rush in general?

The state of Rush in general … Well, I'd say I can't really tell you much other than that there are zero plans to tour again. As I said earlier, we're very close and talk all the time, but we don't talk about work. We're friends, and we talk about life as friends. I can't really tell you more than that, I'm afraid. I would say there's no chance of seeing Rush on tour again as Alex, Geddy, Neil. But would you see one of us or two of us or three of us? That's possible.

Hopefully either way we'll hear another solo album one of these years.

I appreciate the vote of confidence. I do think about it, and I think once the dust settles from this project, I'll probably find myself bored and wandering down to the studio to try to enliven my own life, and if something of a positive nature happens down there, I'll take it to the next step. But beyond that, I could only guess.

It is fair to say you do have ideas you've built up over time?

I have bits and bobs, but I don't have any finished material in the can, so to speak. If I pick up a bass, I just start playing something, and sooner or later I start writing a riff or this or that. So for my own peace of mind, I stash it somewhere. Chances are I'll come back to it, and it's crap, so I just trash it. But at least it makes me feel good for the moment [laughs].